Acneiform and Sweat Gland Disorders

Andrea L. Zaenglein

Acneiform disorders

Neonatal acne (neonatal cephalic pustulosis)

Neonatal acne (acne neonatorum) is a very common newborn eruption, occurring in up to 20% of healthy babies. Lesions are not present at birth but typically appear within the first 2–3 weeks of life and generally improve by about 4 months of age. Small inflammatory red-pink papules and pustules predominate, occurring symmetrically on the cheeks (Fig. 25.1). The forehead, chin, eyelids, scalp, neck, back and chest can be affected as well (Fig. 25.2). Open comedones and nodules are rarely evident, and if present, suggest the possibility of true acne vulgaris, which should be treated according to infantile acne recommendations (see below).

The diagnosis of neonatal acne is usually made clinically. Giemsa staining of pustule contents reveals neutrophils and variable yeast spores. The term ‘neonatal cephalic pustulosis’ (NCP) was proposed to help differentiate this common neonatal eruption from true acne.1,2 In contrast to the androgen-driven infantile acne vulgaris, the pathogenesis of neonatal acne is unclear. Increased sebum and the presence of yeast flora have been implicated as possible triggers. It is known that newborn sebum excretion rates correlate with maternal sebum excretion rates perinatally and these levels subsequently decrease over the next several weeks.3 This suggests that both mother and baby are subject to the same hormonal stimulus following birth. Along with these changes, the baby begins to undergo colonization of normal flora. Malassezia furfur, M. sympodialis and other species frequently colonize neonatal skin, with prevalence rates of 35–50% at 1 week of age and increasing with age, peaking at around 90% by 3–6 months of age.4 However, Malassezia species are not uniformly cultured from the pustules of neonatal acne nor does the degree of colonization appear to correlate with severity of the clinical findings.5 Hence, the role of yeast in the pathogenesis of neonatal acne remains controversial.

The differential diagnosis of acneiform lesions in the neonatal and infantile period is broad (Box 25.1). More florid cases of neonatal acne are sometimes indistinguishable from seborrheic dermatitis, very early onset atopic dermatitis, miliaria rubra and in rare instances, congenital candidiasis. In atypical cases, serial follow-up and close scrutiny for lesions on other body sites is recommended. The condition is self-limited and treatment is rarely required. However, in pronounced cases, topical imidazoles, such as clotrimazole or ketoconazole cream, or a low potency topical corticosteroid, such as hydrocortisone 1% cream, may be helpful in accelerating resolution.

Infantile acne vulgaris

In contrast to neonatal ‘acne’ – a very common condition – infantile acne vulgaris is relatively uncommon. The age of onset is usually between 6 and 12 months, with most cases resolving by 1–3 years.6 Boys are more commonly affected than girls.6–8 Clinically, it is characterized by classic acne lesions occurring primarily on the cheeks. An admixture of open and closed comedones, alone or with inflammatory papules, pustules and small nodules are seen (Figs. 25.3, 25.4). Severe forms with deep, suppurative nodules have been reported.9

The pathogenesis of infantile acne centers on a physiologic increased production of adrenal and gonadal androgens intrinsic to this stage of development. During the first 6–12 months of life, infant boys have elevated levels of luteinizing hormone with a resultant increased production of testosterone.10 In addition, the infantile adrenal gland, in both boys and girls, is still immature with an enlarged zona reticularis that produces elevated levels of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). DHEA is subsequently converted by the sebaceous gland into more potent, acne-promoting androgens, like dihydrotestosterone.11 By 12 months, adrenal androgen levels typically decrease, remaining low until the onset of adrenarche. Testicular androgen production is also minimal throughout childhood.12 It is important to note that the majority of affected babies do not have an overt pathologic cause of hyperandrogenism and laboratory workup is usually unnecessary.6 However, a complete hormonal evaluation is indicated in any infant with acne that is unusually severe, persistent, or if the child has other signs of hyperandrogenism or precocious puberty, such as breast development, testicular hypertrophy, penile or clitoral enlargement, or the presence of axillary or pubic hair. Causes of infantile hyperandrogenism are listed in Box 25.2. The role of genetics in infantile acne is undoubtedly strong with 25–50% of patients reporting a positive family history of severe adolescent acne and 25% noting a sibling with infantile acne.6,7 Most cases of infantile acne resolve by 2–3 years of age, though in some cases, it can last up to age 5 years.13

It is important to treat even mild cases of infantile acne because scarring is fairly common in this age group. Up to 50% of infants with acne develop resultant pitted scars on their cheeks (Fig. 25.5).7 Treatment with a mild retinoid, such as adapalene 1% gel or tretinoin 0.025% cream, may be used daily with a benzoyl peroxide 2.5% cream. Certain formulations such as washes and alcohol based gels should be avoided in infants due to risk of irritating the eyes and skin. For more severe inflammatory lesions, oral erythromycin, azithromycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (in infants 2 months and older) can be used. For the very rare cases of severe nodular acne, use of oral isotretinoin is effective.14 As with other forms of acne, treatment for several months is often needed, with gradual tapering of medications as the condition improves.

Drug-induced acne

Acne and acne-like lesions have been reported from the use of several medications. Most notably, high dose systemic corticosteroids can cause an acneiform eruption in childhood. The lesions are characteristically monomorphous pink-red papules and pustules erupting on the face, chest, shoulders and upper back. Chloracne, most commonly reported due to industrial or incidental exposure to the toxic hydrocarbon, dioxin, can also cause acne in infants and children.15 Open comedones and small nodules predominate, often involving the malar region and ears, extending to involve the nape of the neck. The central face is spared. Other potential causes of medication-induced acne are listed in Box 25.1.

Acne associated with apert syndrome

Apert syndrome, or acrocephalosyndactyly, is characterized by craniosynostoses, midface hypoplasia and symmetric syndactyly of the bones of the hands and feet. Defects in skin, skeleton, brain, and visceral organs are commonly associated. Most cases are sporadic, but autosomal dominant and mosaic forms are reported. Apert syndrome is caused by a missense mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 (FGFR2) gene that encodes the FGFR2 protein. Interestingly, somatic mutations in the FGFR2 gene have been found in several cases of mosaic nevus comedonicus (acneiform unilateral nevus).16 This growth factor protein is vital for numerous cell processes including cell division, growth regulation and maturation, formation of blood vessels, wound healing, embryonic development and malignancy. Patients with Apert syndrome develop pronounced seborrhea with atypical acne lesions, involving the forearms, buttocks and thighs early in puberty, but to date this has not been described in early infancy.17 The acneiform lesions are notably resistant to standard acne treatments and isotretinoin is often required to control the process.18

Hyper-IgE syndrome

More than 80% of patients with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome (AD-HIES, Job syndrome) report a neonatal papulopustular eruption, most often affecting the face and scalp.19–21 Approximately 24% of babies with autosomal recessive hyper-IgE syndrome (AR-HIES) also have a similar indistinguishable eruption.22 The rash usually appears before 2 months of age, with the majority of cases occurring at or within the first 2 weeks after birth. The predominant lesions are crusted papules and small pustules that will wax and wane in severity. Pruritus is a common feature. The rash is associated with peripheral eosinophilia, elevated IgE levels and variable leukocytosis.19 By age 18 months, most affected infants also develop a generalized xerotic, papular and follicular eczematous dermatitis concentrated on the upper body. A classic atopic dermatitis pattern is seen more frequently in AR-HIES (see Chapter 15).21 The eczematous rash may be secondarily impetiginized by Staphylococcus aureus and recurrent abscesses are typical. Over time, a pattern of recurrent infections begins to develop. Affected children develop recurrent bacterial pneumonia, commonly caused by S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae. Opportunistic organisms, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci and secondary fungal infections can also occur, leading to significant morbidity.23 Chronic candidal infections of the oral mucosa, nails, and gastrointestinal tract are also described. Recurrent and resistant cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, human papillomavirus, and molluscum contagiosum, characterize AR-HIES and are uncommon features of the autosomal dominant form of the disease.21 Additionally, cutaneous malignancy, developing early in adulthood is seen almost exclusively in AR-HIES.21 Later in childhood, other defining features of AD-HIES become evident. These include a characteristic facies (defined by a coarse texture to the facial skin, a broad nasal bridge and a bulky nasal tip), retention of primary teeth, hyperextensibility of the joints, tortuous medium-sized blood vessels, osteopenia and bone fractures.

Histopathologic evaluation of the facial skin eruption is nonspecific but may show eosinophilic spongiotic dermatitis or eosinophilic folliculitis. Laboratory investigations reveal a nonspecific leukocytosis with eosinophilia. Despite the name ‘hyper-IgE syndrome’, serum IgE levels in infancy may be only moderately elevated, indistinguishable from elevations caused by atopy. Diagnosis can be suspected because of the clinical features and confirmed with genetic testing. The differential diagnosis of the early papulopustular eruption includes common neonatal eruptions, such as neonatal acne and miliaria. As the other features of HIES develop, the differential diagnosis expands to include eczematous rashes in association with recurrent infections, including severe atopic dermatitis, tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency (hyper-IgE syndrome with atypical mycobacteriosis), Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, Netherton syndrome, Omenn syndrome and other causes of neonatal erythroderma (see Chapter 18).

The autosomal dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome is due to mutations in the STAT3 gene, with the majority of cases resulting from de novo mutations in the gene. The autosomal recessive form is due to mutations in the DOCK8 gene.

Management of hyper-IgE syndrome is aimed at prevention and directed treatment of infections as well as typical skin therapy for atopic dermatitis. Treatment with topical corticosteroids, antifungal creams and oral antibiotics are variably effective.

Pseudoacne of the nasal crease

The transverse nasal crease is a horizontal anatomical demarcation line between the alar cartilage and the triangular cartilage at the lower-third of the nose. Transverse nasal crease can be familial and seen more commonly in atopic patients associated with an ‘allergic salute’.24 Within this developmental fault line, milia, cysts and comedones can form (Fig. 25.6).25 When lesions rupture or are traumatized, inflammatory papules result. The histology of these lesions reveal foreign body granulomatous inflammation.26 This entity is primarily seen in school-age children (4–12 years of age) prior to the onset of puberty, but may be seen earlier, with resolution occurring within months to years.26 Treatment of open comedones consists of surgical expression as needed. Topical retinoids and benzoyl peroxide have been used with variable results.

Childhood flexural comedones

In childhood flexural comedones, noninflamed, open comedones are noted bilaterally or unilaterally in the axilla.27 The groin, neck and antecubital fossa are less commonly involved. The lesions appear in early childhood with one congenital case described. Males and females are equally affected.27 Several of the reported patients had associated molluscum contagiosum infection.27 The lesions do not follow any segmental or Blaschkoid pattern as seen with nevus comedonicus.28 Some authors suggest that childhood flexural comedones could be related to hidradenitis suppurativa.27

Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma

Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG; also known as ‘pyodermite froide du visage’) is characterized by one or more persistent, asymptomatic, inflammatory nodules most often located on the cheek. Lesions are typically red to purple and soft to slightly rubbery. The lesion size varies, with a mean diameter of 10 mm (range 3–25 mm) (Fig. 25.7). Most patients have only a solitary lesion, however some have two or three. While most involve the mid-cheek, other sites including the lateral cheek infraorbital skin, or eyelids can be involved.29 While the etiology is unknown, the association with concomitant eyelid chalazia has led some authors to speculate whether this entity is a variant of granulomatous rosacea.30,31,32

Histopathologic evaluation reveals chronic granulomatous inflammation comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and many foreign body type giant cells. No shadow cells, cyst walls or calcium deposition should be evident. Cultures for bacteria, fungus and mycobacteria are negative, although a few reported cases were deemed secondarily positive to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species and Enterococcus faecalis.29 Ultrasonography shows a well-demarcated, hypoechoic dermal nodule without calcification.

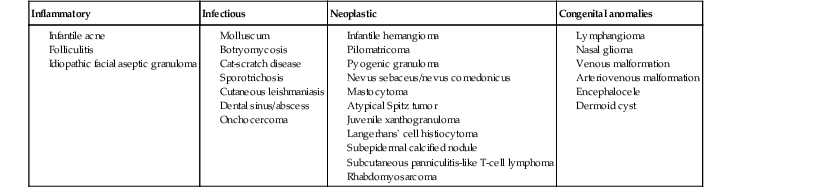

The differential diagnosis includes infantile acne, folliculitis, atypical Spitz tumor, resolving infantile hemangioma, pilomatricoma, and pyogenic granuloma. Infectious etiologies should also be considered, including botryomycosis, cat-scratch disease, sporotrichosis and cutaneous leishmaniasis. Table 25.1 details an expanded differential diagnosis of nodular lesions on the face of a young child.

TABLE 25.1

Differential diagnosis of a nodule on the face of newborns and infants

| Inflammatory | Infectious | Neoplastic | Congenital anomalies |

Treatment of IFAG is often unnecessary as the lesions can resolve spontaneously, though this may take many months. Macrolide antibiotics (azithromycin, erythromycin and clarithromycin) have been used for 2 weeks to 2 months with variable improvement. Topical metronidazole cream has also been used. In persistent cases, incision and drainage or surgical excision can be performed.29

Childhood rosacea

Childhood rosacea is thought to be rare in young children; however, several authors argue that it is more common than generally appreciated because other relatively common childhood conditions such as perioral dermatitis (as well as IFAG) are actually variants of rosacea.30–33

Childhood rosacea is observed more commonly in females with an average age of 4.2 years.33 It has been reported in infants as young as 1 year of age.33 A family history of rosacea is reported in 15% of patients with ocular rosacea.34 Four subtypes are described: papulopustular, telangiectatic, granulomatous and ocular. Children diagnosed with rosacea typically present with a combination of ocular and cutaneous symptoms similar to the findings in adult rosacea. The papulopustular variant is most common with small, erythematous inflamed papules and pustules noted in a malar distribution (see Fig. 25.9). Telangiectasia and macular erythema with or without flushing are common. Ocular manifestations include blepharitis with meibomian gland inflammation and recurrent chalazia, hyperemia, photophobia, episcleritis, or keratoconjunctivitis, and rarely corneal ulceration.33,35 The presence of childhood chalazion (stye) is associated with a higher prevalence of rosacea in adulthood.36

Childhood rosacea is a clinical diagnosis and biopsy is rarely indicated. The differential diagnosis is that of other infantile papulopustular eruptions. Notably, while Demodex mites can be associated with adult rosacea, their presence has not been documented in the childhood form.33 Treatment of rosacea in infants consists of topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, or niacinamide. In refractory or extensive cases, oral erythromycin or azithromycin may also be employed. For ocular symptoms, systemic erythromycin or azithromycin is often used in conjunction with topical ocular erythromycin or metronidazole ophthalmic gel, ocular steroid preparations and diligent eyelid hygiene.33,34

Periorificial dermatitis

Periorificial dermatitis is an acneiform eruption that commonly occurs in infants and young children. There is slight female predominance. The rash is characterized by small inflammatory papules and pustules grouped around the mouth, nose and eyes (Figs. 25.8, 25.9). The lesions can meld into scaling patches or plaques and the margins around the mouth are often spared. The rash is usually asymptomatic but itching and rarely burning can be associated. The spectrum of involvement is broad and numerous terms have been used to describe this entity including perioral dermatitis, perioral or periorificial granulomatous dermatitis and facial Afro-Caribbean eruption.

Some patients have a granulomatous form of periorificial dermatitis characterized by well-formed small pink or skin-colored flattened papules and micronodules, which can become confluent into plaques with a striking perioral demarcation (Fig. 25.10). The perinasal folds and periocular skin are often affected; blepharitis and chalazion can also be seen. Extrafacial involvement has been described with more generalized presentations involving the trunk, extremities and vulvar skin.37 Small pit-like scarring can ensue in severe cases.37 Some experts believe periorificial dermatitis is a form of childhood rosacea.38 The pathogenesis of periorificial dermatitis is unclear but several factors are thought to be contributory. Topical corticosteroids, systemic or inhaled corticosteroids, are thought to precipitate, or at least prolong, the eruption in many cases.39,40 Other possible associations include the use of skin moisturizers, secondary fusobacteria, and Candida albicans.

The diagnosis of periorificial dermatitis is made clinically, although a biopsy may be useful in atypical cases. Histologically, periorificial dermatitis can resemble rosacea with perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with variable perifollicular granulomas.41 In cases of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, the histologic appearance can mimic sarcoidosis with upper dermal and perifollicular granulomas admixed with lymphocytes.42

The differential diagnosis of periorificial dermatitis includes seborrheic dermatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, acne vulgaris, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, steroid-induced rosacea, and demodicosis. For granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, the differential diagnosis expands to include granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, fungal or mycobacterial infection and familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Blau syndrome). Vulvar and perioral involvement may mimic cutaneous Crohn’s disease.

A variety of treatments have been reported for use in the management of childhood periorificial dermatitis.43 In mild cases associated with corticosteroid use, simply discontinuing the steroid may suffice. Alternate therapies include topical antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents including metronidazole cream or gel, clindamycin gel or lotion, erythromycin gel, azelaic acid cream and sodium sulfacetamide lotion. Topical pimecrolimus cream has also been used to treat periorificial dermatitis and to diminish flares from topical steroid withdrawal. Oral erythromycin or azithromycin may be added for refractory or severe cases. Topical corticosteroid use should be avoided as it tends to perpetuate the eruption. Long-standing cases may take many months to resolve and occasional, less severe flares are not uncommon.

Demodicosis

Demodex (D. folliculorum and D. brevis) are commensal mites that reside in the pilosebaceous units of humans. While they are absent, or in very low numbers during early childhood, their numbers increase with age. However, increased numbers of follicular Demodex in childhood are noted in malignancy and malnourished states.44 Demodex folliculitis has been reported primarily in immunocompromised children (e.g., acute lymphocytic leukemia, AIDS and occasionally other conditions), although cases in healthy children have been reported.45–49 Clinical findings of Demodex folliculitis include small erythematous papules and fine scale, most often located on the face, resembling periorificial dermatitis in a haphazard distribution (Fig. 25.11A). Reported cases in children have also included cases of scalp demodicosis mimicking favus, marginal blepharitis demodicosis, Demodex folliculitis and perioral dermatitis or rosacea-like demodicosis.46,48,50,51 A diagnosis of demodicosis is made clinically but can usually be confirmed with direct microscopy of a scraping of follicular contents with either immersion oil or KOH preparation (Fig. 25.11B). There are numerous reported treatments for demodicosis. In young children, initial treatment with permethrin 5% cream, topical metronidazole 1% gel, or topical sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% formulation is suggested. Response is highly variable and sometimes multiple treatment modalities are needed to achieve clinical improvement.

Granulosis rubra nasi

This very rare disorder presents with bright red erythema associated with prominent perspiration localized predominantly to the nose, with occasional involvement of the cheeks and chin. Small inflammatory papules, small clear vesicles and telangiectasia and have been described as well. It is noted that a clear rhinorrhea often accompanies the localized cutaneous findings.52 Most cases are reported in childhood, with onset as early as birth.53 Familial cases have also been described as well as one report with pheochromocytoma.54,55 If required, treatment with intralesional botulinum toxin A can result in clinical improvement.56

Keratosis pilaris

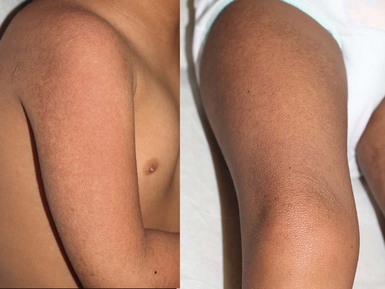

Keratosis pilaris is a very common disorder of childhood with a prevalence of 2–20%.57 Most cases are noted with onset in infancy or early childhood. Small, coarse, dry, follicular papules with variable erythema are symmetrically distributed most commonly on the proximal extensor surfaces of the arms and cheeks with generalized versions affecting the thighs, buttocks, distal extremities and the trunk (Fig. 25.12). A generalized, papular form of keratosis pilaris is described occurring in a subset of infants.58 The papules are larger and widely spread over the entire extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, involving the cheeks as well. The lesions are typically asymptomatic except when inflamed. In inflammatory keratosis pilaris, pustules admixed with excoriated papules can be observed.

The etiology of keratosis pilaris is unknown. An autosomal dominant inheritance pattern is suspected as greater than 50% of those affected have a positive family history.59 The disorder is associated with ichthyosis vulgaris and atopy; including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.59,60 Additionally, it is reported to be seen with higher frequency in patients with diabetes mellitus, obesity and Down syndrome.61–64 Typically keratosis pilaris improves in the warmer summer months and worsens in the winter.59 The natural history is noted to have three possible outcomes. In about one-third, the disorder improves by the late teen years. In 40%, the lesions remain stable; and in 20% the disorder worsens over time.59

Treatments for keratosis pilaris are often ineffective and very rarely curative. Emollients alone are recommended for use in newborns and infants due to risk of irritation and potential toxicity from other treatments. In older children, topical retinoids or keratolytic agents, including urea, glycolic acid, ammonium lactate and salicylic acid, can be tried. Topical corticosteroids should be used only for short periods to alleviate pruritic symptoms in inflamed lesions.

Keratosis pilaris variants

When keratosis pilaris is associated with pronounced erythema, the term keratosis pilaris rubra is used.57 The redness is striking and overshadows the papular elements of the disorder. The facial distribution is often widespread, involving the lateral cheeks, eyebrows, chin and pinnae of the ears, giving a distinctly ruddy appearance. Extrafacial involvement may also be extensive, with involvement of the extensor surfaces of the arms, legs and often the chest, back, and buttocks (Fig. 25.13). No atrophy or hyperpigmentation is noted. While often having onset during infancy, keratosis pilaris rubra, unlike most other forms of keratosis pilaris, tends to persist into adolescence.

Another keratosis pilaris variant is erythromelanosis follicularis faciei et colli.65 This entity is characterized by prominent well-demarcated, reddish-brown pigmentation, telangiectasia, and pale follicular papules localized to the lateral cheeks often extending to the neck. Generalized involvement is not seen with this form. Adolescent onset has been reported.

Keratosis pilaris atrophicans is a group of follicular keratodermas considered a variant of keratosis pilaris. They are defined by hyperkeratotic follicular plugs with variable erythema associated with atrophic scarring.

Ulerythema ophryogenes is a keratosis pilaris variant localized to the lateral eyebrows and associated with localized alopecia. It has onset in infancy and is observed more frequently in boys.66 The inheritance is either sporadic or autosomal dominant. Ulerythema ophryogenes is associated with Noonan syndrome and cardio-facial-cutaneous syndrome; as well as wooly hair, monosomy 18p, Cornelia de Lange syndrome and Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome.67–73

Atrophoderma vermiculatum is characterized early on by small, rough follicular papules with minimal erythema that progress to atrophic cribriform scars occurring on the cheeks, preauricular region and forehead. Unilateral involvement has been reported.74,75 Onset typically occurs later in childhood than other forms, generally after 5 years of age.76 Autosomal dominant and sporadic inheritance is suggested.76

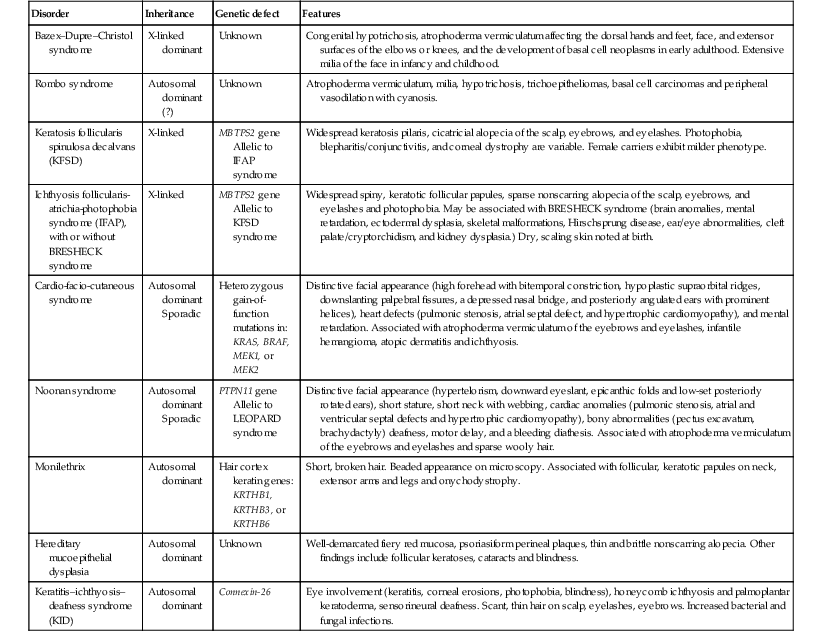

Several genetic associations are noted with these variants and generalized keratosis pilaris, including IFAP (ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia, photophobia) syndrome and cardio-facial-cutaneous syndrome (Figs. 25.14, 25.15). These are outlined in Table 25.2.

TABLE 25.2

Genetic disorders associated with keratosis pilaris

| Disorder | Inheritance | Genetic defect | Features |

| Bazex–Dupre–Christol syndrome | X-linked dominant | Unknown | Congenital hypotrichosis, atrophoderma vermiculatum affecting the dorsal hands and feet, face, and extensor surfaces of the elbows or knees, and the development of basal cell neoplasms in early adulthood. Extensive milia of the face in infancy and childhood. |

| Rombo syndrome | Autosomal dominant (?) | Unknown | Atrophoderma vermiculatum, milia, hypotrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. |

| Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD) | X-linked | MBTPS2 gene Allelic to IFAP syndrome |

Widespread keratosis pilaris, cicatricial alopecia of the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Photophobia, blepharitis/conjunctivitis, and corneal dystrophy are variable. Female carriers exhibit milder phenotype. |

| Ichthyosis follicularis-atrichia-photophobia syndrome (IFAP), with or without BRESHECK syndrome | X-linked | MBTPS2 gene Allelic to KFSD syndrome |

Widespread spiny, keratotic follicular papules, sparse nonscarring alopecia of the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes and photophobia. May be associated with BRESHECK syndrome (brain anomalies, mental retardation, ectodermal dysplasia, skeletal malformations, Hirschsprung disease, ear/eye abnormalities, cleft palate/cryptorchidism, and kidney dysplasia.) Dry, scaling skin noted at birth. |

| Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome | Autosomal dominant Sporadic | Heterozygous gain-of-function mutations in: KRAS, BRAF, MEK1, or MEK2 | Distinctive facial appearance (high forehead with bitemporal constriction, hypoplastic supraorbital ridges, downslanting palpebral fissures, a depressed nasal bridge, and posteriorly angulated ears with prominent helices), heart defects (pulmonic stenosis, atrial septal defect, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), and mental retardation. Associated with atrophoderma vermiculatum of the eyebrows and eyelashes, infantile hemangioma, atopic dermatitis and ichthyosis. |

| Noonan syndrome | Autosomal dominant Sporadic | PTPN11 gene Allelic to LEOPARD syndrome |

Distinctive facial appearance (hypertelorism, downward eyeslant, epicanthic folds and low-set posteriorly rotated ears), short stature, short neck with webbing, cardiac anomalies (pulmonic stenosis, atrial and ventricular septal defects and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), bony abnormalities (pectus excavatum, brachydactyly) deafness, motor delay, and a bleeding diathesis. Associated with atrophoderma vermiculatum of the eyebrows and eyelashes and sparse wooly hair. |

| Monilethrix | Autosomal dominant | Hair cortex keratin genes: KRTHB1, KRTHB3, or KRTHB6 | Short, broken hair. Beaded appearance on microscopy. Associated with follicular, keratotic papules on neck, extensor arms and legs and onychodystrophy. |

| Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia | Autosomal dominant | Unknown | Well-demarcated fiery red mucosa, psoriasiform perineal plaques, thin and brittle nonscarring alopecia. Other findings include follicular keratoses, cataracts and blindness. |

| Keratitis–ichthyosis–deafness syndrome (KID) | Autosomal dominant | Connexin-26 | Eye involvement (keratitis, corneal erosions, photophobia, blindness), honeycomb ichthyosis and palmoplantar keratoderma, sensorineural deafness. Scant, thin hair on scalp, eyelashes, eyebrows. Increased bacterial and fungal infections. |

Disseminated congenital comedones and idiopathic disseminated comedones

These disorders are characterized by disseminated, hyperkeratotic, follicular-based papules with comedo-like plugging. The congenital case involves the face, trunk, and upper arms, including the flexural surfaces.77 Slight improvement is noted at 2 years. The acquired case begins on the buttocks and spreads to involve the thighs, shoulders, and arms.78 The lesions become notably inflamed and purulent and heal with depressed, crateriform scarring. The differential diagnosis includes widespread keratosis pilaris, perforating disorders, and familial dyskeratotic comedones.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa (also known as trichodysplasia or pilomatrix dysplasia of immunosuppression, cyclosporine-induced folliculo-dystrophy, or viral/virus-associated trichodysplasia) is a rare complication of immunosuppression characterized by spiny, exophytic follicular projections occurring over the midface and cheeks. The shoulders, arms, and legs may also be affected. An associated acneiform eruption may predate and continue in association with the spiny papules.79 Loss of eyebrows has also been associated. It has been reported in children as young as 5 years79 but, to date, not in infants.

Active polyomavirus has been identified in the majority of cases and is suspected as the cause.80 The seroprevalence of polyomavirus is 5% in children 1–4 years, increasing to 48% by age 6–10.81 Various immunosuppressants and combinations have been associated including mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, tacrolimus and cyclosporine. It has been reported in patients who underwent solid organ transplant, as well as in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Histologically, there is abnormal follicle maturation, overgrowth of the inner root sheath epithelium and hyperkeratosis of the infundibulum. Intranuclear viral particles can be seen on electron microscopy.

Topical cidofovir 3% cream has been effective in some cases, as well as topical tazarotene 0.1% cream, and oral valganciclovir. In several cases, the lesions resolved when the immunosuppression was eventually discontinued.

Eccrine gland disorders

Eccrine hidradenitis

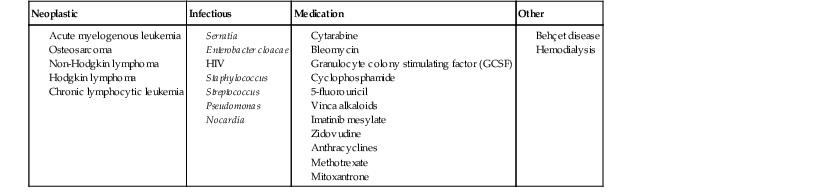

Several forms of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) have been reported. These include childhood neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, palmoplantar eccrine hidradenitis, as well as chemotherapy-associated neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Associations of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis are listed in Table 25.3![]() .

.

TABLE 25.3

Associations of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis

| Neoplastic | Infectious | Medication | Other |

Childhood neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis

Childhood neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (CNEH) is an idiopathic form described in infants and toddlers.82 In CNEH, urticarial, red nodules and plaques are primarily localized to the arms and legs. The trunk and scalp can also be involved. Generalized forms have also been observed.83 The lesions can be tender but are often asymptomatic. The typical age range of a child with CNEH varies from 6 to 14 months, with a median age of 9.1 months.82 It is seen almost exclusively in the hot summer months. An elevated white count is common and an increased C-reactive protein can be seen.

Histopathologic evaluation reveals a dense neutrophilic infiltrate concentrated around the ductal and secretory portions of the eccrine duct. No leukocytoclastic vasculitis is seen.

The etiology of CNEH is unknown and affected children are otherwise healthy. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was cultured in a minority of cases making its association unclear. However, the clear summertime prevalence and association with excessive heat exposure and sweating may hold a clue to its pathogenesis.84

The differential diagnosis of CNEH includes: urticaria, erythema multiforme, miliaria, erythema nodosum, arthropod bites, papular urticaria, atypical viral exanthema, and Sweet syndrome.

Lesions typically resolve in approximately 3 weeks. Topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents have all been used to alleviate any symptoms and questionably, speed resolution.

Palmoplantar eccrine hidradenitis

Palmoplantar eccrine hidradenitis is characterized by tender, pink to red papules and nodules localized to the palms and soles (Fig. 25.16).85 This form is typically seen in school-aged children and adolescents and is often associated with heat, moisture and physical activity. Children as young as 4 years old have been reported.86 Management consists of rest, elevation, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Lesions resolve over days to weeks, with recurrences quite common. Palmoplantar eccrine hidradenitis typically arises within 1–2 weeks after starting chemotherapy, manifesting as painful, bright pink-red papules, nodules and plaques on the trunk, extremities, and face. Linear, annular, pustular, and purpuric forms have been reported. Generally, patients are febrile and neutropenic, secondary to the underlying malignancy.

Histopathologic examination classically reveals vacuolar degeneration within the secretory portion of the eccrine duct along with a neutrophilic infiltrate. Inflammation may be sparse, however, in severely neutropenic patients. Squamous metaplasia is sometimes seen.

Chemotherapy.

NEH was originally described in association with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) being treated with chemotherapy, particularly cytarabine; however, many other chemotherapeutic agents have subsequently been implicated. Corticosteroids and dapsone can be effective in treatment. Lesions resolve shortly after discontinuation of chemotherapy.

Hyperhidrosis

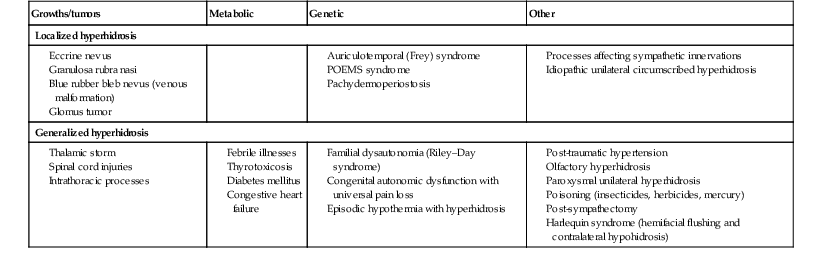

Causes of hypohidrosis and hyperhidrosis are varied, including genetic and acquired disorders of the skin and nervous system. Depending on the cause, the effects can be localized or generalized. A list of disorders that result in impaired sweating are given in Tables 25.4 and 25.5.

TABLE 25.4

Causes of hyperhidrosis in neonates and infants

| Growths/tumors | Metabolic | Genetic | Other |

| Localized hyperhidrosis | |||

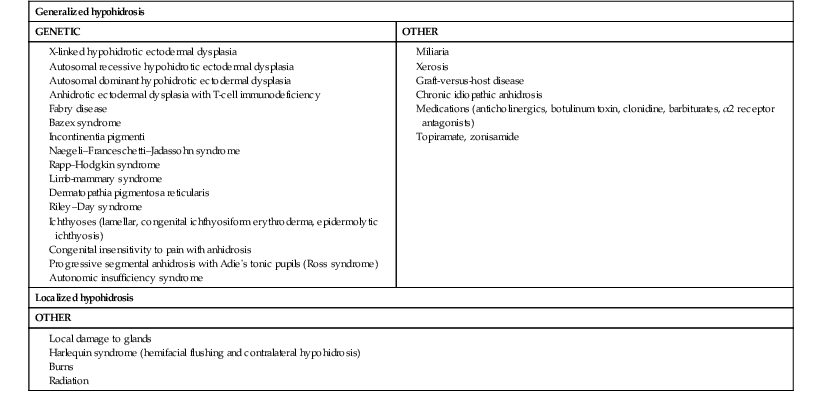

TABLE 25.5

Causes of hypohidrosis

Auriculotemporal nerve syndrome (frey syndrome)

This syndrome is associated with prominent unilateral facial flushing and sweating along the path of the auriculotemporal nerve. It typically appears in infancy, between 2 and 6 months of age, with the introduction of solid foods. Flushing in noted immediately within seconds of mastication and episodes last up to 1 hour.87 Symptoms tend to improve slowly over several years. Bilateral and familial variants have been reported, likely due to congenital anomalies of the nerve.88 Unlike in adults, gustatory sweating is not common in infancy, and cases with just flushing are described. Damage to the nerve during delivery, particularly from use of forceps, is noted in more than 50% of cases.87 Other reported associations include buccal tumors such as plexiform neurofibroma associated with neurofibromatosis type 1,89 congenital hemangiopericytoma90 and as a complication of parotidectomy.

Due to the association with eating, auriculotemporal nerve syndrome is often initially confused with food allergy. The differential diagnosis also includes Harlequin syndrome.

Harlequin syndrome

Harlequin syndrome (hemifacial flushing with contralateral hypohidrosis; not to be confused with Harlequin ichthyosis and Harlequin color change) is a rare disorder of autonomic dysfunction characterized by unilateral hypohidrosis with compensatory contralateral flushing and sweating associated with tearing and rhinorrhea (Fig. 25.17). Episodes of intense erythema defined by the midline are often triggered by heat or exercise. Neurologic and/or ocular symptoms such as Horner syndrome may be present. This syndrome may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary (due to neck tumors, vascular compromise of the cervical chain or brainstem injury). It is postulated that the syndrome could be an exaggerated response on the side opposite to the sympathetic deficit side, serving as a compensatory mechanism to maintain normal heat regulation.91

Hypohidrosis and anhidrosis

Hypohidrosis and anhidrosis are rare conditions in newborns and infants. Most genetic cases are attributable to ectodermal dysplasias, which are discussed in Chapter 29.

Congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis

Congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis is an autosomal, recessive hereditary sensory neuropathy due to a defect in the NTRK1 gene.92 Affected children will have normal numbers of sweat glands on biopsy but have markedly impaired functioning, with no clinical sweating. Fever is often the presenting symptom and uncontrolled hyperthermia can result in death. Other findings include mental retardation and self-mutilation. Traumatic lingual ulceration (Riga–Fede disease) presenting as granulomatous exophytic plaques on the lips and tongue can occur in infants with inherited insensitivities to pain.93

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Table 3 is available online at ExpertConsult.com ![]()