Chapter 24 Acne vulgaris

AETIOLOGY

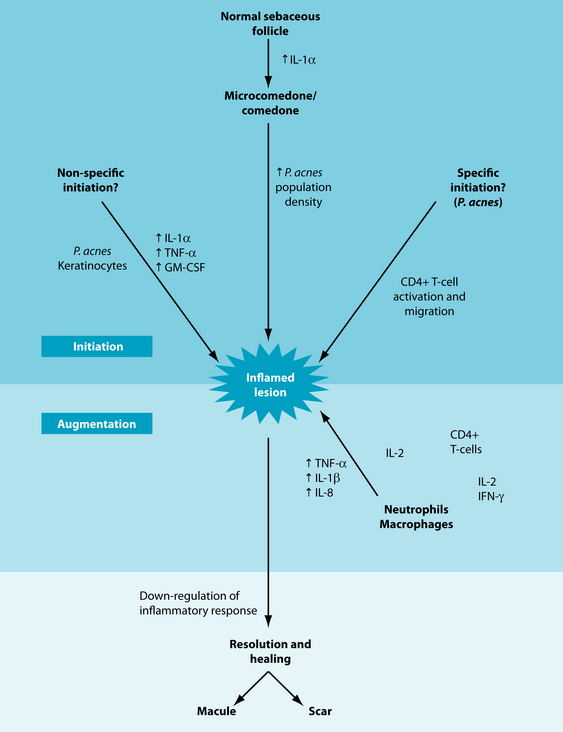

Acne vulgaris is a condition typified by inflammation of the pilosebaceous follicles in the skin.1 It is characterised by a variety of lesions including nodules, papules, pustules and open and closed comedones. However, the sequence of the pathophysiological development of these lesions is still unclear. The dominant hypothesis at this stage focuses on increased circulating androgens stimulating sebaceous gland activity, and the resulting sebum production triggering hyperkeratosis. This process blocks the follicle and results in dilation and the ultimate formation of a comedone.1 The transition from a comedone to a lesion such as a pustule, papule or nodule is believed to be due to a bacterium, called Propionibacterium acnes, colonising the follicle and triggering an inflammatory response within the follicle wall.2 This cascade involves T helper cells (CD4+), most likely subtype T helper 1, and macrophages, which infiltrate the local area, possibly as a result of antigenic stimulation. The antigen identified as the most likely initiator of inflammation is Propionibacterium acnes (see the box below). This trigger is believed to develop due to weakness in the follicular basement membranes, associated with reduced linoleic acid levels in the follicular wall. This has been explained through increased sebum production depleting local fatty acid stores. Once an inflammatory cascade has begun, hyperproliferation of follicles can occur. As keratinised cells and sebum compact within the follicular lumen, a ‘horny plug’ forms. This process ultimately results in the development of a comedone and is referred to as ‘comedonegenesis’.2

RISK FACTORS

Predisposing and exacerbating factors relating to the development of acne vulgaris include hereditary predisposition, premenstrual hormonal fluctuations, increased androgen levels, heavy or irritating clothing, backpacks or helmets, the application of oily creams, the use of certain drugs and exposure to increased heat and humidity.5 Some dietary factors, such as dairy intake6 or glycaemic load,7 may also increase the risk of acne; however, specific attributable risk in this area remains unclear until further research is done.

PROPIONIBACTERIUM ACNES

Propionibacterium acnes was initially considered the cause of acne vulgaris following its identification in acne lesions in 1896. This has been supported by evidence of a failure of antibiotic treatment of acne due to erythromycin-resistant strains of P. acnes. However, more recent research has determined that P. acnes may trigger or exacerbate acne vulgaris, but it is not the only factor. In fact, some acne lesions do not have any sign of bacterial infection. It is now considered that P. acnes is not the primary cause of acne, although it is still considered a significant contributor to the inflammation.3,4 P. acnes is more commonly connected with the appearance of pustules, rather than the least severe comedones. This occurs due to the bacteria breaking down sebum into specific fatty acids, which trigger an inflammatory response. The inflammation weakens the dermal layer and opportunistic staphylococcal organisms invade, forming a pustule.5

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Treatment of acne vulgaris focuses on the bacterial and hormonal aetiology of the condition. The hormonal mainstays of medical intervention include oral contraceptives and antiandrogen medication (spironolactone, cyproterone acetate or flutamide).8 Approaching acne management through hormonal regulation is justified through the presence of androgen receptors in the basal layer of sebaceous glands and in the outer root sheath keratinocytes in the hair follicle. Oral contraceptives interfere with the stimulation of these receptors by reducing ovarian production of androgens, while the other antiandrogen medications act as receptor blockers.8 Topical management through the use of peeling agents (benzoyl peroxide, tretinoin or isotretinoin) and antibacterial agents (tetracycline) are also commonly used to control lesions.5

The most common drug used in severe, chronic acne vulgaris is isotretinoin. Isotretinoin affects epidermis health through a number of mechanisms, including promotion of epidermal cell differentiation, stimulation of keratinocyte proliferation and reduction of sebaceous gland size (by suppressing the proliferation of basal sebocytes and sebum production). Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties have also been identified. Isotretinoin is usually prescribed on average for 20 weeks, with a starting dose of between 0.5 and 1 mg/kg/day and concomitant prescription of oral antibiotics for the first 4 weeks of treatment.9

Naturopathic management of patients taking this medication needs to be approached carefully due to potential side effects of oral retinoid therapy (see the box below). Individuals who have been prescribed isotretinoin should avoid pregnancy, due to potential congenital malformations associated with the drug. There is also a risk of psychiatric conditions such as depression, psychoses and suicidal thoughts. It is also worth noting that, however rare, liver conditions such as acute hepatitis can be triggered through isotretinoin therapy and, because of this, hepatoprotective interventions may be worth considering. At the very least ethanol extracts of herbs may need to be modified to reduce potentially compounding the impact upon liver health. Most commonly, however, isotretinoin affects mucous membranes and can cause cheilitis, dry eyes, dry mouth, dry skin and desquamation of lips.10 Furthermore, recent research has also identified elevated serum homocysteine levels in patients with cystic acne undergoing isotretinoin therapy,11 as well as decreased plasma folate concentrations.12 The health implications of these results are discussed in more detail

POTENTIAL SIDE EFFECTS OF ISOTRETINOIN THERAPY

The side effects of isotretinoin therapy are essentially the same as vitamin A toxicity (hypervitaminosis A syndrome) and include the following:9

in Section 3 on the cardiovascular system. Some possible complementary prescriptions that may support individuals taking isotretinoin include zinc, methionine, arginine, vitamin E, soy protein, fish oil and L-carnitine. However, any inclusion of these interventions in the treatment plan would require careful and close monitoring as research in this area is still preliminary.10

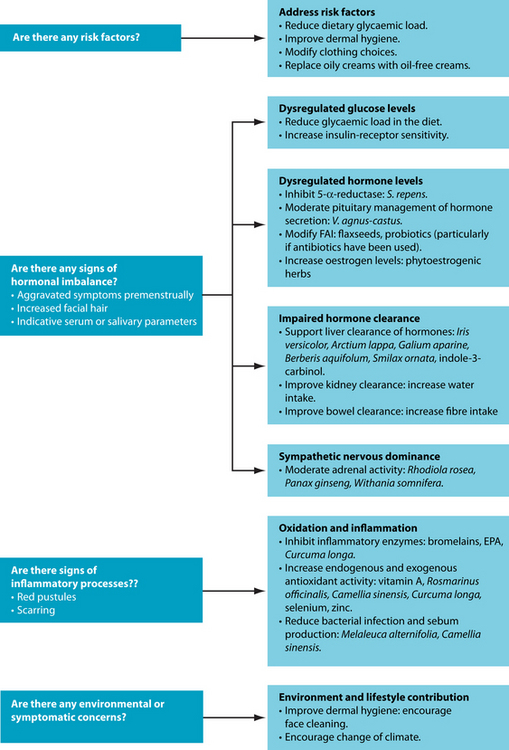

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

Hormone modulation

The sebaceous glands, and the skin in general, are sites for androgen synthesis within the human body. In fact, prior to puberty, the sebaceous glands, particularly in the face and scalp, are the primary sites of androgen conversion from adrenal precursor hormones such as DHEA-S. All key enzymes required to convert cholesterol to androgens, particularly testosterone, are locally present within the sebaceous gland. Androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, are understood to be involved in both the regulation of cell proliferation and lipogenesis. In contrast, oestrogens are understood to inhibit excessive sebaceous gland activity, possibly by increasing androgen binding to its binding globulin.3,13

Management of acne focusing specifically on the elevated androgen levels includes the application of herbs such as Serenoa repensSerenoa repens acts to reduce the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone through inhibition of the enzyme responsible, 5-α-reductase. Although no research is apparently specifically related to acne vulgaris, successful outcomes have been found when using this herb in a range of other androgen-dominant conditions.14–16 A different approach to the herbal management of hormone modulation often considered in acne vulgaris is Vitex agnus-castus.17 V. agnus-castus has been traditionally used for the regulation of hormonal conditions particularly focusing on sexual and reproductive functions,18 and this has been supported through more recent research identifying dopaminergic and oestrogenic compounds extracted from the herb.19 Another herbal intervention to be considered is a kampo (traditional Japanese medicine) combination formula of Paeonia spp. and Glycyrrhiza spp., which has been found to reduce testosterone and improve oestrogen/testosterone ratio in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome.20 Although the exact mechanism is unclear, it has been argued that this occurs due to an increased aromatase activity, thereby converting testosterone to 17β-oestradiol, and/or central nervous system activity resulting in an increase in pituitary secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone.20

Similarly, other natural substances may be used in the management of acne vulgaris, although not yet specifically investigated for the condition, based upon their known activity within the body. For example, enterolactone, a phytoestrogenic compound derived from flaxseed, has been found to reduce the Free Androgen Index.21 However, this substance is activated from precursors found in flaxseed by the microflora found in the human colonic intestinal tract; this microflora may be affected by the use of oral antibiotics.22

FREE ANDROGEN INDEX (FAI)

The Free Androgen Index (sometimes called the Testosterone Free Index, or TFI) is determined by calculating the ratio of the total testosterone concentration to the concentration of sex hormone binding globulin. It often increases in severe acne, hirsutism, polycystic ovarian syndrome and male androgenic alopecia (male-pattern baldness).34

Androgens and the stress response

Research has found that the symptoms of acne vulgaris are worse in times of psychological stress. Physiological adaptation to stress may also be a contributing factor to acne vulgaris due to the hormonal cascade this produces. In particular, increased physiological stress results in hypothalamic secretion of noradrenalin and thereby corticotrophic-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH then stimulates release of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary. The primary target of ACTH is the adrenal cortex through which it affects adrenal androgen secretion.23 Furthermore, CRH also inhibits secretion of gonadotrophic releasing hormone, resulting in lower gonadic hormones, thereby further exacerbating the androgen:oestrogen imbalance often seen in acne vulgaris.23 For this reason, herbs that have adaptogenic activity may be considered (see Chapter 8 on respiratory disorders) including Rhodiola rosea,24 Panax ginseng and Withania somnifera.25

Androgen metabolism and clearance

Naturopathically, the skin has been referred to as ‘the third kidney’. The rationale behind this statement is the role the skin plays in detoxification of the system. Both phase I and phase II detoxification enzymes are found in human skin. The phase I enzymes are mostly represented by alcohol dehydrogenase; however, CYP450 enzymes are also present although at much lower levels.26 The subtypes of CYP450 found in

ALTERATIVES AND DEPURATIVES

Historically, naturopaths have emphasised the importance of detoxification to manage a number of conditions including renal, urinary, hepatic, endocrine and skin disease.32 It is explained by Benedict Lust in his seminal text that ‘the origin of all is again to be readily explained by accumulations of foreign matter; and here we have especially to do with the accumulations affecting the normal function of those organs so important for the secretion of waste matter from the body: the kidneys and the skin’.32 This is the foundation upon which the herbal medicine management of skin disorders was originally based: the use of alteratives and depuratives. An alterative or depurative has been defined as a herb that ‘improves detoxification and aids elimination to reduce the accumulation of metabolic waste products within the body’.28 Herbs that are traditionally considered to have this action include (but are by no means limited to) Iris versicolor, Arctium lappa, Galium aparine, Echinacea spp., Chionanthus virginicus, Berberis aquifolium, Smilax ornata and Rumex crispus. However, it is interesting to note that no current research validating the empirical use of these herbs has been found. This is an important area within naturopathic management of skin diseases, and such research would provide great benefit to evidence-based naturopathic practice.

the skin are generally involved in hydroxylation of a number of compounds, including retinoids, prostanoids, inflammatory mediators, arachidonic acid and cholesterol. In contrast, the phase II enzymes are expressed in high concentrations. These include glutathione-S-transferase, catechol-O-methyltransferase and steroid sulfotransferase.26 Likewise, aromatase has been found in high concentrations in sebaceous glands and may act to clear excess androgens.27 This implies that the skin does have an important role in detoxification, particularly through phase II enzymes. It also suggests that compromised or stressed liver detoxification may place further burden on the skin, thereby aggravating dermal conditions such as acne vulgaris. With this in mind, it may be more accurate to refer to the skin as the ‘second liver’ rather than the third kidney.

Clearance of excess hormones and other aggravating substances has historically been managed naturopathically using depurative herbs. These herbs are associated with improved detoxification and elimination of metabolic wastes.28 There are a number of herbs which have been traditionally used for chronic skin disorders, including Iris versicolor, Arctium lappa, Galium aparine, Berberis aquifolium and Smilax ornata (see the box on alteratives and depuratives for more information). However, very little modern research has been undertaken investigating the benefits of these herbs in acne vulgaris.17 More recently, naturopaths have been using an extract from cruciferous vegetables, known as indole-3-carbinol, to stimulate hepatic metabolism of excess steroidal hormones, including androgens.29 Like the depurative herbs, however, there is no specific research linking this compound with acne vulgaris, but understanding its mechanism of action does suggest some potential clinical benefit.

In contrast to these beneficial interventions, cigarette smoking and tobacco-related products have been found to inhibit aromatase activity,30 and as such may exacerbate acne vulgaris, but this has not yet been supported through epidemiological research.31

Androgens and diet

A potential confounding factor within hormone imbalances related to acne may come from the diet.6 For example, milk intake as a teenager has been associated with an increased incidence of acne. The researchers found that these results were not linked to saturated fat intake as skim milk consumption had a higher association. The researchers hypothesised that the hormonal content of the milk may be a contributing factor, particularly for adolescent females, but this requires further investigation.

Likewise, a diet with a high glycaemic load can result in increased plasma levels of glucose, insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), all of which have been associated with an increased Free Androgen Index13 (see the box above). By following a low-glycaemic load and high protein diet, researchers have found reduced lesion count, reduced FAI and increased IGF binding protein-1.7 However, research in this area is still inconclusive due to conflicting results.33

Inflammation, infection and topical management

Immune modulation to reduce inflammation and bacterial infection of the acne lesions is another important component of the naturopathic management of acne vulgaris. This is often achieved through minimising oxidation, decreasing physiological stress and reducing inflammatory triggers such as elevated blood glucose levels and bacterial infection of the lesion. However, more direct anti-inflammatory approaches may also be included in the treatment of acne vulgaris. One such option is quercetin, a compound synthesised by plants, with a known anti-inflammatory effect through inhibition of TNF-α, NFкB, IL-2 and IFNγ.35 Another commonly used compound is bromelain, derived from pineapples. Bromelain is an enzyme complex that acts to reduce inflammation, although the exact mechanism requires further clarification.36

Oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators

Oxidative stress has been found to be increased in patients with acne vulgaris; however, it is unclear whether this is a cause or symptom.37 However, as oxidative stress has been linked to inflammatory responses, it is an important factor to address when managing this condition.

Dietary intake of trans-fatty acids, found in margarines, spreads, frying and cooking oils,38 has been associated with increased inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein,39 TNF receptor-1 and TNF receptor-2.40 For this reason, it is recommended that dietary intake of processed and deep-fried foods be reduced in individuals with acne vulgaris.

Furthermore, compromised levels of dietary antioxidants have been linked with acne vulgaris. One study identified a strong relationship between low levels of vitamin A and vitamin E and acne. In fact, it was found that levels in the lower quintile were associated with the severity of the condition.41 The link between oxidative stress and acne vulgaris also suggests that medicinal herbs with known antioxidant activity, such as Rosmarinus officinalis,42 Camellia sinensis42 and Curcuma longa0 may be beneficial.43 However, it must be noted that no known clinical research has been undertaken investigating the oral use of these herbs in acne vulgaris.

Nutrients such as selenium44 and zinc45 also have known antioxidant activity and may be beneficial in reducing oxidative stress in acne vulgaris. Selenium has undergone preliminary clinical trials for patients with acne vulgaris, particularly focusing on improving erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase (an endogenous antioxidant enzyme that

Figure 24.1 Events in the evolution of an inflammatory acne lesion

source: Farrar MD, Ingham E. Ache: inflammation. Clinics in Dermatology 2004;22:380–384.

relies on selenium as a cofactor) activity.46 The clinical significance of this research is not yet clear, although it is known that lower glutathione peroxidase levels are found in patients with acne compared with controls.47 Clinical research for oral zinc supplements in acne vulgaris has also been undertaken, and found to result in mild but statistically significant improvements.48,49

Stress and the inflammatory response

Cutaneous tissue is the site of a complex system of autocrine and paracrine functions that are stimulated by prostaglandins. Increased inflammatory response stimulates a cascade of stress hormone release, which begins with corticotrophic-releasing hormone and culminates in the release of cortisol, thereby generating an anti-inflammatory response. However, the expression of CRH receptors is modulated by hormones such as testosterone and oestrogen.3 This process is supported by the well-accepted evidence that acne vulgaris is aggravated by mental stress. This may be explained by stimulation of the HPA axis under stress, causing an increase in adrenal secretion of cortisol and androgens.50 This further supports the potential benefits associated with the adaptogenic herbs mentioned above, and also suggests that herbs with both anti-inflammatory and adrenal tonic activity such as Glycyrrhiza glabra28 may be beneficial.

Topical treatments and antimicrobial activity

Medical management of acne vulgaris usually incorporates an aspect of antibacterial and topical treatments, and naturopathic approaches are no different. Essential oils are often used topically on acne lesions with the main focus of such treatments being antimicrobial activity. Such an example is Cymbopogon nardus, which has been identified through an in vitro study to exert antimicrobial activity on Propionibacterium acnes.51 Another study compared Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil with benzoyl peroxide, a common topical antibacterial treatment.52 This study found both treatments to be effective, although the M. alternifolia had a slower response rate and fewer side effects. In fact, in vitro research53 has found that P. acnes is susceptible to M. alternifolia at concentrations as low as 0.25%.

Topical application of Camellia sinensis has also been investigated in relation to sebum production. A recent animal study54 found that a number of green tea catechins (including epigallocatechin-3-gallate) reduced sebocyte proliferation, and other compounds such as kaempferol reduce sebocyte lipogenesis. This potential treatment has been further explored using patients with acne vulgaris and a 2% ‘tea lotion’;55 however, the exact formula of the tea lotion was not defined and as such the clinical relevance is unclear.

Preliminary research has identified a polysaccharide found in Camellia sinensis extracts that reduces Propionibacterium acnes adhesion to human cutaneous tissue.56 This research needs to be expanded further to explore the application of green tea extract on topical acne lesions, but the implications are promising. In contrast, a small human study investigating the effect of topical application of Curcuma longa in reducing acne inflammation found no benefit.57

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Psychotherapy

One such consideration is psychotherapy. Given the physiological impact of stress on the pathogenesis of acne and the importance of emotional health to overall wellbeing, it is important to consider counselling as an important therapy adjunctive to acne

management. The basic acknowledgment of emotional responses such as embarrassment and low self-image is an important part of this process and can be implemented from the first consultation.58

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is another method of treatment to be considered. Blue light phototherapy has been trialled recently for acne management,59 and was found to reduce lesions (although not to affect P. acnes colonies). A similar result has also been found for red light phototherapy.60

Hygiene considerations

Skin hygiene is a controversial consideration within a treatment regimen associated with the management of acne vulgaris. Some preliminary research has found that the difference between showering immediately after exercise-induced sweating and waiting 4 hours before showering made no statistically significant difference to the symptoms of acne.61 Similar research was conducted regarding face-washing and acne, comparing groups using a standard mild cleanser and washing once, twice and four times a day for 6 weeks.62 The group washing twice per day had improvements in both open comedones and non-inflammatory lesions; however, there appeared to be no real advantage to washing more frequently than this. Hygiene considerations more generally—such as higher environmental bacterial levels on floors, bedding and so on—have been implicated in other skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and therefore could be considered.63

Ayurvedic medicine

Ayurvedic medicine may also provide some support in the management of acne vulgaris. An in vitro study was undertaken to explore the effect of a number of Ayurvedic herbs on inflammatory mediators associated with P. acnes infection and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris.64 Of the herbs studied, Rubia cordifolia, Curcuma longa, Hemidesmus indicus, Azadirachta indica and Sphaeranthus indicus were found to reduce the inflammatory mediators interleukin-8 and tumour necrosis factor-α, and to inhibit reactive oxygen species (free radicals). Curcuma longa and Hemidesmus indicus are often used in Western herbal medicine, but it is worth noting that the extraction process for the herbs used was reflective of practices used in Ayurvedic medicine and may not directly correspond with ethanol-based extracts as used in Western herbal medicine.

Example treatment

Prescription

In this example case, the approach to treatment is to improve metabolite clearance and reduce the effect of exacerbating factors, while providing agents to reduce inflammation and promote connective tissue healing. The herbal formula as shown in the treatment box includes herbs selected due to their vulnerary (C. officinalis, C. asiatica and H. perforatum), anti-inflammatory (C. asiatica and C. officinalis), depurative (C. asiatica), adaptogenic (C. asiatica and S. chinensis), anti-depressant (H. perforatum and S. chinensis) and nervine tonic (H. perforatum, S. chinensis and C. asiatica) activity.28,65 Further support of the internal herbal formula is provided through the topical wash consisting of C. officinalis, C. sinensis and M. alternifolia.

Herbal formula

| Calendula officinalis 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Centella asiatica 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Hypericum perforatum 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Schisandra chinensis 1:2 | 25 mL |

| 5 mL b.d. | 100 mL |

The treatment aims are also supported through the use of a nutritional formula containing selenium, vitamin A, vitamin E, bromelains, quercetin and zinc to assist in reducing inflammation and oxidation, while promoting connective tissue repair.36,66,67 However, it is vital that this is combined with dietary recommendations to reduce sugar and refined carbohydrate intake, and increase consumption of unprocessed grains and whole foods. Finally, it is also important to encourage more lifestyle balance, particularly by increasing the amount of time spent on enjoyable activities, to assist in the reduction of stress response.

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

Given that the patient in the example case is young and living away from home for the first time on a student’s income, it is important to develop her prescription carefully, taking in to account her cooking skills, time commitments and budget. As such, her supplements have been restricted to one herbal and one nutritional formula at a time, thereby minimising the financial pressure. The dietary recommendations proposed also take her life skills into consideration. The first consultation provides some gentle recommendations that work within her current diet and do not involve very expensive food or

a lot of meal preparation. This can then be modified when she returns, has experienced some successes and is keen to take on further changes.

It may take 2 to 3 months of consistent treatment before results are noticed with acne vulgaris. In fact, it may be beneficial in a condition such as this to have less frequent consultations. Rather than seeing a patient fortnightly, this may need to spread out to 4 to 8 weeks. This is particularly important if hormonal imbalance is a strong contributing factor for the individual. If blood sugar irregularities become evident through case taking, and basic dietary changes are not addressing them, further investigation may be necessary. Specifically, a glucose tolerance test (with insulin) may identify subacute glucose intolerance or pancreatic insufficiency. If this is the case the treatment regimen will need to be modified to incorporate a stronger focus in this area. Particularly useful treatment options here include Gymnema sylvestre68 and magnesium69 (see Section 5 on the endocrine system for more information).

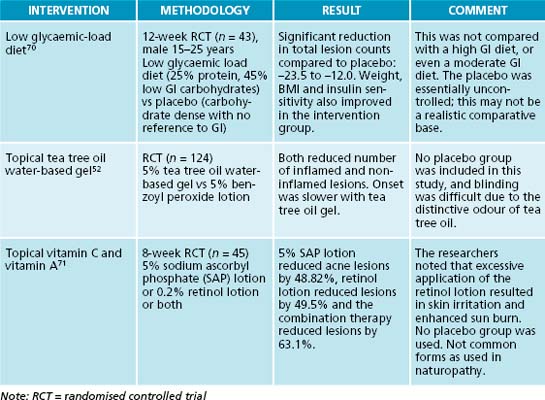

Cordain L. Implications for the role of diet in acne. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2005;24:84-91.

Desai A., et al. Systemic retinoid therapy: a status report on optimal use and safety of long-term therapy. Drug Actions, Reactions, and Interactions. 2007;25(2):185-193.

Farrar M.D., Ingham E. Acne: inflammation. Clinics in Dermatology. 2004;22:380-384.

Jaffer S.N., Qureshi A.A. Dermatology quick glance. USA: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003.

1. Olutunmbi Y., et al. Adolescent female acne: etiology and management. 2008;21(4):171-176.

2. Holland D.B., Jeremy A.H.T. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of acne and acne scarring. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2005;24:79-83.

3. Zouboulis C.C. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clinics in Dermatology. 2004;22:360-366.

4. Farrar M.D., Ingham E. Acne: inflammation. Clinics in Dermatology. 2004;22:380-384.

5. Gould B.E. Pathophysiology for the health professional, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

6. Adebamowo C.A., et al. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:207-214.

7. Smith R.N., et al. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:247-256.

8. George R., et al. Hormonal therapy for acne. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2008;27:188-196.

9. Desai A., et al. Systemic retinoid therapy: a status report on optimal use and safety of long-term therapy. Dermatologic Clinics. 2007;25(2):185-193.

10. Hanson N., Leachman S. Safety issues in isotretinoin therapy. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2001;20(3):166-183.

11. Polat M., et al. Plasma homocysteine level is elevated in patients on isotretinoin therapy for cystic acne: a prospective controlled study. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19(4):229-232.

12. Chanson A., et al. Decreased plasma folate concentration in young and elderly healthy subjects after a short-term supplementation with isotretinoin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(1):94-100.

13. Danby F.W. Diet and acne. Clinics in Dermatology. 2008;26:93-96.

14. Prager N., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of botanically derived inhibitors of 5-alpha-reductase in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(2):143-152.

15. Talpur N., et al. Comparison of saw palmetto (extract and whole berry) and cernitin on prostate growth in rats. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;250(1–2):21-26.

16. Wadsworth T.L., et al. Effects of dietary saw palmetto on the prostate of transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model (TRAMP). Prostate. 2007;67(6):661-673.

17. Yarnell E., Abascal K. Herbal medicine for acne vulgaris. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2006;12(6):303-309.

18. Felter H.W., Lloyd J.U. King’s American dispensary, 18th edn. Portland: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1905. reprinted 1983

19. Jarry H., et al. In vitro assays for bioactivity-guided isolation of endocrine active compounds in Vitex agnus-castus. Maturitas. 2006;55(Suppl 1):S26-S36.

20. Takahashi K., Kitao M. Effect of TJ-68 (shakuyaku-kanzo-to) on polycystic ovarian disease. International Journal of Fertility. 1994;39(2):69-76.

21. Demark-Wahnefried W., et al. Pilot study of dietary fat restriction and flaxseed supplementation in men with prostate cancer before surgery: exploring the effects on hormonal levels, prostate-specific antigen, and histopathologic features. Urology. 2001;58(1):47-52.

22. Kilkkinen A., et al. Use of oral antimicrobials decreases serum enterolactone concentration. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155(5):472-477.

23. Charmandari E., et al. Endocrinology of the stress response 1. Annual Review of Physiology. 2005;67(1):259-284.

24. Spasov A.A., et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the stimulating and adaptogenic effect of Rhodiola rosea SHR-5 extract on the fatigue of students caused by stress during an examination period with a repeated low-dose regimen. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(2):85-89.

25. Bhattacharya S.K., Muruganandam A.V. Adaptogenic activity of Withania somnifera: an experimental study using a rat model of chronic stress. Pharmacology, biochemistry and behaviour. 2003;75(3):547-555.

26. Luu-The V., et al. Analysis of phases 1 and 2 metabolism enzymes in human skin suggests important role of phase 2 enzymes in the detoxification. Toxicology Letters. 2008:180S. s121

27. Chen W., et al. Cutaneous androgen metabolism: basic research and clinical perspectives. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2002;119(5):992-1007.

28. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. Missouri: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

29. Jellinck P.H., et al. Distinct forms of hepatic androgen 6β-hydroxylase induced in the rat by indole-3-carbinol and pregnenolone carbonitrile. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1994;51(3–4):219-225.

30. Osawa Y., et al. Aromatase inhibitors in cigarette smoke, tobacco leaves and other plants. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 1990;4(2):187-200.

31. Firooz A., et al. Acne and smoking: is there a relationship? BMC Dermatology. 2005;5(1):2.

32. Lust B. Universal buyer’s guide naturopathic encyclopaedia directory and yearbook for drugless therapy 1918–1919. New York: Lust and Butler; 1918.

33. Kaymak Y. Dietary glycemic index and glucose, insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3, and leptin levels in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:819-823.

34. Vankrieken L. Testosterone and the free androgen index. www.diagnostics.siemens.com: Siemens Diagnostic, 2000.

35. Sun Yu E., et al. Regulatory mechanisms of IL-2 and IFN[gamma] suppression by quercetin in T helper cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;76(1):70-78.

36. Taussig S.J., Batkin S. Bromelain, the enzyme complex of pineapple (Ananas comosus) and its clinical application. An update. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1988;22(2):191-203.

37. Arican O., et al. Oxidative stress in patients with acne vulgaris. Mediators of Inflammation. 2005;6(2005):380-384.

38. Hulshof K.F.A.M., et al. Intake of fatty acids in Western Europe with emphasis on trans fatty acids: the TRANSFAIR study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;53(2):143-157.

39. Lopez-Garcia E., et al. Consumption of trans fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J Nutr 2005. March 1, 2005;135(3):562-566.

40. Mozaffarian D., et al. Dietary intake of trans fatty acids and systemic inflammation in women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(4):606-612.

41. El-akawi Z., et al. Does the plasma level of vitamins A and E affect acne condition? Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2006;31(3):430-434.

42. Chen H.-Y., et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of aqueous extract of some selected nutraceutical herbs. Food Chemistry. 2007;104(4):1418-1424.

43. Kumar G.S., et al. Free and bound phenolic antioxidants in amla (Emblica officinalis) and turmeric (Curcuma longa). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2006;19(5):446-452.

44. Elango N., et al. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant status in stage (III) human oral squamous cell carcinoma and treated with radical radio therapy: Influence of selenium supplementation. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2006;373(1–2):92-98.

45. Mariani E., et al. Effects of zinc supplementation on antioxidant enzyme activities in healthy old subjects. Experimental Gerontology. 2008;43(5):445-451.

46. Michaelsson G., Edqvist L.E. Erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase activity in acne vulgaris and the effect of selenium and vitamin E treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64(1):9-14.

47. Aybey B., et al. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) enzyme levels of patients with acne vulgaris. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2005;19(6):766-767.

48. Goransson K., et al. Oral zinc in acne vulgaris: a clinical and methodological study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;58(5):443-448.

49. Dreno B., et al. Low doses of zinc gluconate for inflammatory acne. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69(6):541-543.

50. Tanida M., et al. Relation between mental stress-induced activity and skin conditions: a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Brain Research. 2007;1184:210-216.

51. Lertsatitthanakorna P., et al. In vitro bioactivities of essential oils used for acne control. International Journal of Aromatherapy. 2006;16(1):43-49.

52. Bassett I.B., et al. A comparative study of tea-tree oil versus benzoylperoxide in the treatment of acne. Medical Journal of Australia. 1990;153(8):455-458.

53. Carson C.F., Riley T.V. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1994;19(1):24-25.

54. Kim J.K., et al. Evaluation of skin sebosuppression by components of total green tea (Camellia sinensis) extracts. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2008;17(3):464-469.

55. Sharquie K.E., et al. Topical therapy of acne vulgaris using 2% tea lotion in comparison with 5% zinc sulphate solution. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(12):1757-1761.

56. Lee J.-H., et al. Inhibition of pathogenic bacterial adhesion by acidic polysaccharide from green tea (Camellia sinensis). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54:8717-8723.

57. Shaffrathul J.H., et al. Turmeric: role in hypertrichosis and acne. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2007;52(2):116.

58. Panconesi E., Hautmann G. Psychotherapeutic approach in acne treatment. Dermatology. 1998;196(1):116.

59. Ammad S., et al. An assessment of the efficacy of blue light phototherapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7(3):180-188.

60. Na J.I., Suh D.H. Red light phototherapy alone is effective for acne vulgaris: randomized, single-blinded clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(10):1228-1233.

61. Short R.W., et al. A single-blinded, randomized pilot study to evaluate the effect of exercise-induced sweat on truncal acne. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(1):126-128.

62. Choi J.M., et al. A single-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial evaluating the effect of face washing on acne vulgaris. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(5):421-427.

63. Leung A., et al. Severe atopic dermatitis is associated with a high burden of environmental Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(5):789-793.

64. Jain A., Basal E. Inhibition of Propionibacterium acnes-induced mediators of inflammation by Indian herbs. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:34-38.

65. British Herbal Medicine Association. British herbal pharmacopoeia. London: British Herbal Medicine Association; 1996.

66. Kohlmeier M. Nutrient metabolism. San Diego: Academic Press; 2003.

67. Gropper S.S., et al. Advanced nutrition and human metabolism, 5th edn. Belmont: Wadsworth; 2009.

68. Sugihara Y., et al. Antihyperglycemic effects of gymnemic acid IV, a compound derived from Gymnema sylvestre leaves in streptozotocin-diabetic mice. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2000;2(4):321-327.

69. Paolisso G., et al. Magnesium and glucose homeostasis. Diabetologia. 1990;33(9):511-514.

70. Smith R.N., et al. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(1):107-115.

71. Ruamrak C., et al. Comparison of clinical efficacies of sodium ascorbyl phosphate, retinol and their combination in acne treatment. International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 2009;31(1):41-46.