12 Acid-Base Disorders

General Principles

General Principles

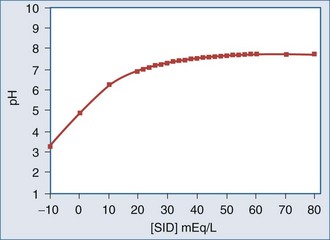

Three widely accepted methods are used to analyze and classify acid-base disorders, yielding mutually compatible results. The approaches differ only in assessment of the metabolic component (i.e., all three treat PCO2 as an independent variable): (1) HCO3− concentration ([HCO3−]); (2) standard base-excess; (3) strong ion difference. All three yield virtually identical results when used to quantify the acid-base status of a given blood sample.1–4 For the most part, the differences among these three approaches are conceptual; in other words, they differ in how they approach the understanding of mechanism.5–7

There are three mathematically independent determinants of blood pH:

Assessing Acid-Base Balance

Assessing Acid-Base Balance

Metabolic Acid-Base Disorders

Metabolic Acid-Base Disorders

Pathophysiology of Metabolic Acid-Base Disorders

Disorders of metabolic acid-base balance occur as a result of:

The Kidneys

Normal plasma flow to the kidneys is approximately 600 mL/min in adults. The glomeruli filter the plasma to yield about 120 mL/min of filtrate. Normally, more than 99% of the filtrate is reabsorbed and returned to the plasma. Thus, the kidney can only excrete a very small amount of strong ions into the urine each minute, and several minutes to hours are required to achieve a significant impact on SID. The handling of strong ions by the kidney is extremely important because every Cl− ion that is filtered but not reabsorbed decreases SID. Accordingly, “acid handling” by the kidney is generally mediated through changes in Cl− balance. The purpose of renal ammoniagenesis is to allow the excretion of Cl− without Na+ or K+. Viewed this way, renal tubular acidosis can be regarded as an abnormality of Cl− handling rather than of H+ or HCO3− handling.3

Renal-Hepatic Interaction

Ammonium ion (NH4+) is important to systemic acid-base balance not because it stores H+ or has a direct action in the plasma (normal plasma NH4+ concentration is <0.01 mEq/L). NH4+ is important because it is “co-excreted” with Cl−. Of course, NH4+ is not only produced in the kidney. Hepatic ammoniagenesis (and, as we shall see, glutaminogenesis) is also important for systemic acid-base balance and is tightly controlled by mechanisms sensitive to plasma pH.8 This reinterpretation of the role of NH4+ in acid-base balance is supported by the evidence that hepatic glutaminogenesis is stimulated by acidosis.9 Glutamine is used by the kidney to generate NH4+ and thus facilitates the excretion of Cl−. The production of glutamine, therefore, can be seen as having an alkalinizing effect on plasma pH because of the way the kidney utilizes it.

The Gastrointestinal Tract

Different parts of the GI tract handle strong ions in distinct ways. In the stomach, Cl− is pumped out of the plasma and into the lumen, thereby reducing the SID and pH of gastric juice. The pumping action of the gastric parietal cells increases SID of the plasma by promoting the loss of Cl−; this effect produces the so-called alkaline tide at the beginning of a meal when gastric acid secretion is maximal.10 In the duodenum, Cl− is reabsorbed and the plasma pH is restored. Normally, only slight changes in plasma pH are evident because Cl− is returned to the circulation almost as soon as it is removed. However, if gastric secretions are removed from the patient, either through a suction catheter or as a result of vomiting, Cl− is lost and SID increases. It is important to realize that it is the Cl− loss, not the H+ loss, that is the cause for widening of the SID and the development of metabolic alkalosis. Although H+ is “lost” as HCl, it is also lost with every molecule of water removed from the body.

Metabolic Acidosis

Metabolic Acidosis

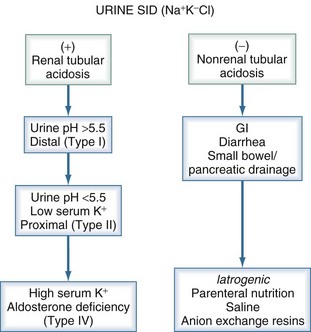

Traditionally, metabolic acidoses are categorized according to the presence or absence of unmeasured anions. The presence of unmeasured anions is routinely inferred by measuring the concentrations of electrolytes in plasma and calculating the anion gap, as described later. The differential diagnosis for a positive–anion gap (AG) acidosis is shown in Box 12-1. Non–anion gap acidoses can be divided into three types: renal, GI, and iatrogenic (Figure 12-1). In the intensive care unit (ICU), the most common types of metabolic acidosis include lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis, iatrogenic acidosis, and acidosis secondary to toxins.

The potential effects of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis on vital organ function are shown in Table 12-1. Metabolic and respiratory acidosis may have different implications with respect to survival, an observation that suggests that the underlying disorder is perhaps more important than the absolute degree of acidemia.11

TABLE 12-1 Potential Clinical Effects of Metabolic Acid-Base Disorders

| Metabolic Acidosis | Metabolic Alkalosis |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Cardiovascular |

| Decreased inotropy | Decreased inotropy (Ca++ entry) |

| Conduction defects | Altered coronary blood flow* |

| Arterial vasodilation | Digoxin toxicity |

| Venous vasoconstriction | |

| Oxygen Delivery | Neuromuscular |

| Decreased oxy-Hb binding | Neuromuscular excitability |

| Decreased 2,3-DPG (late) | Encephalopathy seizures |

| Neuromuscular | Metabolic Effects |

| Respiratory depression | Hypokalemia |

| Decreased sensorium | Hypocalcemia |

| Hypophosphatemia | |

| Impaired enzyme function | |

| Metabolism | Oxygen Delivery |

| Protein wasting | Increased oxy-Hb affinity |

| Bone demineralization | Increased 2,3-DPG (delayed) |

| Catecholamine, PTH, and aldosterone stimulation | |

| Insulin resistance | |

| Free radical formation | |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Emesis | |

| Gut barrier dysfunction | |

| Electrolytes | |

| Hyperkalemia | |

| Hypercalcemia | |

| Hyperuricemia |

2,3-DPG, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate; oxy-Hb, oxyhemoglobin; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

* Animal studies have shown both increased and decreased coronary artery blood flow.

If metabolic acidemia is to be treated, consideration should be given to the likely duration of the disorder. If it is expected to be short lived (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis), maximizing respiratory compensation is usually the safest approach. Once the disorder resolves, ventilation can be quickly reduced to normal, and there will be no lingering effects of therapy. However, if the disorder is likely to be more chronic (e.g., renal failure), therapy aimed at restoring SID is indicated. In all cases, the therapeutic target can be quite accurately determined from the standard base-excess. As discussed, the standard base-excess corresponds to the amount SID must change in order to restore the pH to 7.4, assuming a PCO2 of 40 mm Hg. Thus, if the SID is 30 mEq/L and the standard base-excess is −10 mEq/L, the target SID would be 40 mEq/L. Accordingly, the plasma Na+ concentration would have to increase by 10 mEq/L for NaHCO3 administration to completely repair the acidosis. If increasing the plasma Na+ concentration is inadvisable for other reasons (e.g., hypernatremia), then NaHCO3 administration is also inadvisable. Importantly, NaHCO3 administration has not been shown to improve outcome in patients with lactic acidosis.12

In addition, NaHCO3 administration is associated with certain disadvantages. Large (hypertonic) doses given rapidly can lead to hypotension13 and have the potential to cause a sudden marked increase in PaCO2.14 Accordingly, it is important to assess the patient’s ventilatory status before NaHCO3 is administered, particularly in the absence of mechanical ventilation. NaHCO3 infusion also affects circulating [K+] and [Ca++] concentrations, which need to be monitored closely.

Tromethamine (Tris-buffer or Tham) is an organic buffer that readily penetrates cells.15 It is a weak base (pK = 7.9) that does not alter SID and does not affect plasma [Na+]. Accordingly, it is often used when administration of NaHCO3 is contraindicated because of hypernatremia. This agent has been available since the 1960s, but limited data are available on its use in humans with acid-base disorders. In small uncontrolled studies, tromethamine appears to be effective in reversing metabolic acidosis secondary to ketoacidosis or renal failure without obvious toxicity.16 However, adverse reactions have been reported, including hypoglycemia, respiratory depression, and even fatal hepatic necrosis when concentrations exceeding 0.3 M are used. In Europe, a mixture of tromethamine, acetate, NaHCO3, and disodium phosphate is available (Tribonate). This mixture seems to have fewer side effects than tromethamine alone, but experience with Tribonate is still quite limited.

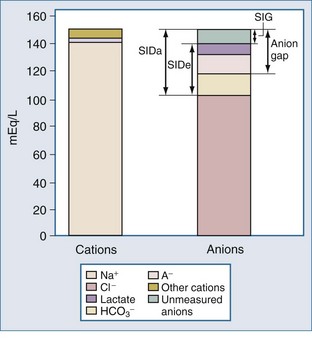

Anion Gap and Strong Ion Gap

For more than 30 years, AG has been used by clinicians, and it has evolved into a major tool to evaluate acid-base disorders.17 AG is estimated from the differences between the routinely measured concentrations of serum cations (Na+ and K+) and anions (Cl− and HCO3−). Normally this difference, or “gap,” is made up by albumin and, to a lesser extent, by phosphate. Sulfate and lactate also contribute a small amount, normally less than 2 mEq/L. However, there are also unmeasured cations, such as Ca++ and Mg++, and these tend to offset the effects of sulfate and lactate, except when the concentration of sulfate or lactate is abnormally increased (Figure 12-2). Plasma proteins other than albumin can be positively or negatively charged, but in the aggregate tend to be neutral except in rare cases of abnormal paraproteins, such as in cases of multiple myeloma.18 In practice, AG is calculated as follows:

Because of its low and narrow extracellular concentration range, K+ is often omitted from the calculation. The normal value for AG is 12 ± 4 (if [K+] is considered) or 8 ± 4 mEq/L (if [K+] is not considered). The normal range has decreased in recent years following the introduction of more accurate methods for measuring Cl− concentration.19,20 However, the various measurement techniques available mandate that each institution reports its own expected “normal anion gap.”

The AG is useful because this parameter can limit the differential diagnosis for patients with metabolic acidosis. If AG is increased, the explanation almost invariably will be found among five disorders: ketosis, lactic acidosis, poisoning, renal failure, or sepsis.21 However, several conditions can alter the accuracy of AG estimation, and these conditions are particularly prevalent among patients with critical illness22,23:

Other factors that can increase AG are low Mg++ concentration and administration of the sodium salts of poorly reabsorbable anions (e.g., beta-lactam antibiotics).25 Certain parenteral nutrition formulations, such as those containing acetate, can increase AG. Citrate-based anticoagulants rarely can have the same effect after administration of multiple blood transfusions.26 None of these rare causes, however, increases AG significantly,27 and they are usually easily identified. In recent years, some additional causes of an increased AG have been reported. It is sometimes widened in patients with nonketotic hyperosmolar states induced by diabetes mellitus; the biochemical basis for this effect remains unexplained.28 In recent years, unmeasured anions have been reported in the blood of patients with sepsis29,30 and liver disease31,32 and in experimental animals injected with endotoxin.33 These anions may be the source of much of the unexplained acidosis seen in patients with critical illness.34

Additional doubt has been cast on the diagnostic value of AG in certain situations, however.22,30 Salem and Mujais22 found routine reliance on AG to be “fraught with numerous pitfalls.” The primary problem with the AG is its reliance on the use of a “normal” range that depends on normal circulating levels of albumin and to a lesser extent phosphate, as discussed earlier. Plasma concentrations of albumin or phosphate are often grossly abnormal in patients with critical illness, leading to changes in the “normal” range for AG. Moreover, because these anions are not strong anions, their charge is affected by pH.

These considerations have prompted some authors to adjust the “normal range” for AG according to the albumin concentration24 or phosphate concentration.6 Each g/dL of albumin has a charge of 2.8 mEq/L at pH 7.4 (2.3 mEq/L at pH 7.0 and 3.0 mEq/L at pH 7.6). Each mg/dL of phosphate has a charge of 0.59 mEq/L at pH 7.4 (0.55 mEq/L at pH 7.0 and 0.61 mEq/L at pH 7.6). Thus, the “normal” AG can be estimated using this formula6:

Or for international units:

These formulas only should be used when the pH is less than 7.35, and even then they are only accurate within 5 mEq/L. When more accuracy is needed, a slightly more complicated method of estimating [A−] is required.31,35

Another alternative to using the traditional AG is to use the SID. By definition, SID must be equal and opposite to the negative charges contributed by [A−] and total CO2. The sum of the charges from [A−] and total CO2 concentration has been termed the effective strong ion difference (SIDe).18 The apparent strong ion difference (SIDa) is obtained by measurement of each individual ion. Both the SIDa and the SIDe should equal the true strong ion difference. If the SIDa and SIDe differ, unmeasured ions must exist. If the SIDa is greater than SIDe, these ions are anions; if the SIDa is less than SIDe, the unmeasured ions are cations. This difference has been termed the strong ion gap to distinguish it from AG.31 Unlike the AG, the strong ion gap is normally zero and does not change with changes in pH or albumin concentration.

Positive–Anion Gap Acidoses

Lactic Acidosis

In many forms of critical illness, lactate is the most important cause of metabolic acidosis.36 Blood lactate concentration has been shown to correlate with outcome in patients with hemorrhagic37 and septic shock.38 Lactic acid has been viewed as the predominant source of metabolic acidosis due to sepsis.39 In this view, lactic acid is released primarily from the musculature and the gut as a consequence of tissue hypoxia. Moreover, the amount of lactate produced is believed to correlate with the total oxygen debt, the magnitude of hypoperfusion, and the severity of shock.36 In recent years, this view has been challenged by the observation that during sepsis, even with profound shock, resting muscle does not produce lactate. Indeed, studies by various investigators have shown that the musculature actually may consume lactate during endotoxemia.40–42 Data concerning the gut are less clear. There is little question that underperfused gut can release lactate; however, it does not appear that the gut releases lactate during sepsis if mesenteric perfusion is maintained. Under such conditions, the mesenteric circulation can even become a net consumer of lactate.40,41 Perfusion is likely to be a major determinant of mesenteric lactate metabolism. In a canine model of sepsis, gut lactate production could not be shown when flow was maintained with dopexamine hydrochloride.42

Studies in animals as well as humans have shown that the lung may be a prominent source of lactate in the setting of acute lung injury.40,43–45 While studies such as these do not address the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of hyperlactatemia in sepsis, they suggest that using blood lactate concentration as evidence for tissue dysoxia is an oversimplification at best. Indeed, many investigators have begun to offer alternative interpretations of hyperlactatemia in this setting.44–48 Box 12-2 lists several alternative sources of hyperlactatemia. In particular, pyruvate dehydrogenase, the enzyme responsible for moving pyruvate into the Krebs cycle, is inhibited by endotoxemia.49 However, data from recent studies suggest that increased aerobic metabolism may be more important than metabolic defects or anaerobic metabolism.50 Finally, administration of epinephrine promotes lactic acidosis, presumably by stimulating cellular metabolism (e.g., increased glycolysis in skeletal muscle).

Administration of epinephrine may be a common cause of lactic acidosis in patients with critical illness.51,52 Interestingly, this phenomenon does not occur when dobutamine or norepinephrine is infused53 and does not appear to be related to decreased tissue perfusion.

A more important mechanism whereby hyperlactatemia exists without acidemia (or with less acidemia than expected) is when the SID is corrected by the elimination of another strong anion from the plasma.54 In the setting of sustained lactic acidosis induced by lactic acid infusion, Cl− moves out of the plasma space, thus normalizing pH. Under these conditions, hyperlactatemia may persist but base-excess may be normalized by compensatory mechanisms to restore the SID.

Traditionally, lactic acidosis is subdivided into type A, in which the mechanism is tissue hypoxia, and type B, in which there is no hypoxia.55 However, this distinction may be artificial. Some disorders, such as sepsis, may be associated with lactic acidosis owing to a variety of mechanisms (see Box 12-2), some of the “A” type and some of the “B” type. A potentially useful method of distinguishing anaerobically produced lactate from other sources is to measure the blood pyruvate concentration. The normal lactate to pyruvate ratio is 10 : 1.56 A lactate-to-pyruvate ratio greater than 25 : 1 is considered to be evidence of anaerobic metabolism.48 This approach makes biochemical sense, because pyruvate is reduced to lactate during anaerobic metabolism, thereby increasing the lactate-to-pyruvate ratio. Unfortunately, pyruvate is very unstable in solution and, therefore, is difficult to measure accurately in the clinical setting, greatly reducing the clinical utility of lactate/pyruvate determinations.

Treatment of lactic acidosis remains controversial. The only noncontroversial approach is to treat the underlying cause. The use of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) is equally controversial and remains of unproven value.12

Ketoacidosis

Another common cause of a metabolic acidosis with a positive AG is ketoacidosis. Ketones are formed by beta-oxidation of fatty acids, a process that is inhibited by insulin. In insulin-deficient states, ketone formation increases substantially. The accumulation of ketone bodies (acetone, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetoacetate) in the plasma is exacerbated because elevated blood glucose concentrations promote an osmotic diuresis, leading to intravascular volume contraction. This state is associated with elevated circulating cortisol and catecholamine levels, which further stimulates free fatty acid production.57 In addition, increased glucagon levels relative to insulin levels decreases intracellular concentrations of malonyl coenzyme A and increases the activity of carnitine palmitoyl acyl transferase, effects that promote ketogenesis.

Both acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate are strong anions (pKa 3.8 and 4.8, respectively).58 Thus, like lactate, the presence of these ions decreases the SID and increases [H+]. Ketoacidosis may result from diabetes (diabetic ketoacidosis) or excessive alcohol consumption (alcoholic ketoacidosis). The diagnosis is established by measuring serum ketone levels. However, it is important to understand that the nitroprusside reaction only measures acetone and acetoacetate, and not β-hydroxybutyrate. Thus, the state of measured ketosis is dependent on the ratio of acetoacetate to β-hydroxybutyrate. This ratio is low when lactic acidosis coexists with ketoacidosis, because the reduced redox state of lactic acidosis favors production of β-hydroxybutyrate.59 In this circumstance, the apparent level of ketosis is small relative to the amount of acidosis and the elevation of AG. There is also a risk of confusion during treatment of ketoacidosis, because ketones as measured by the nitroprusside reaction can increase despite resolving acidosis. This effect occurs as a result of rapid clearance of β-hydroxybutyrate, improving acid-base balance without changing the measured level of ketosis. Furthermore, circulating ketone levels can even appear to increase as β-hydroxybutyrate is converted to acetoacetate. Hence, it is better to monitor therapy by measuring blood pH and AG than by assaying levels of serum ketones.

Treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis includes infusing insulin and large amounts of fluid; 0.9% saline is usually recommended. Potassium replacement is often required as well. Fluid resuscitation reverses the hormonal stimuli for ketone body formation, as discussed earlier, and insulin promotes metabolism of ketones and glucose. Administration of NaHCO3 may produce a more rapid rise in pH by increasing SID, but there is little evidence that this effect is desirable. Furthermore, because increasing the plasma Na+ concentration increases the SID, the SID will be too high once the ketosis is cleared (“overshoot” alkalosis). In any case, administration of NaHCO3 is rarely necessary and should be avoided except in extreme cases.60

A more common problem in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis is persistence of acidemia after resolution of ketosis. This hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis occurs as Cl− replaces ketoacids, thus maintaining decreases in SID and pH. This effect appears to occur for two reasons. First, exogenous Cl− is often provided in the form of 0.9% saline, which, if given in large enough quantities, results in a so-called dilutional acidosis (see later discussion). Second, renal Cl− reabsorption increases as ketones are excreted in the urine. Increases in the tubular Na+ load produce electrical-chemical forces favoring Cl− reabsorption.61

The acidosis seen in patients with alcoholic ketoacidosis is usually less severe. Treatment consists of intravenous (IV) fluid administration and infusion of glucose instead of insulin, as would be the case with diabetic ketoacidosis.62 Indeed, insulin is contraindicated because it may cause precipitous hypoglycemia.63 Thiamine also must be given to avoid precipitating Wernicke encephalopathy.

Renal Failure

Renal failure, especially when chronic, leads to accumulation of sulfates and other acids, widening AG, although this increase usually is not large.64 Similarly, uncomplicated renal failure rarely produces severe acidosis, except when it is accompanied by a high rate of acid generation, such as occurs during hypermetabolism.65 In all cases, SID is decreased and remains so unless some therapy is provided. Hemodialysis removes sulfate and other ions and allows normal Na+ and Cl− balance to be restored, thus returning SID to normal (or near normal). However, patients not yet requiring dialysis and those who are between treatments often require some other therapy to increase SID. NaHCO3 is used as long as the plasma Na+ concentration is not already elevated.

Toxins

Metabolic acidosis with an increased AG is a major feature of various types of drug and substance intoxications (see Box 12-1).

Other and Unknown Causes

In the nonketotic hyperosmolar state associated with poorly controlled diabetes, AG widens for unexplained reasons.28 Even when very careful methods are applied using the strong ion gap or similar strategies, unmeasured anions have been detected in the blood of patients with sepsis29,30 and liver disease31 and in experimental animals given endotoxin.32 Furthermore, unknown cations also appear in the blood of some critically ill patients.30 The significance of these findings remains to be determined.

Non–Anion Gap (Hyperchloremic) Acidoses

Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis occurs as a result of either the increase in [Cl−] relative to strong cations, especially Na+, or the loss of cations with retention of Cl−. As seen in Figure 12-1, these disorders can be separated by history and by measurement of urinary Cl− concentration. When acidosis occurs, the normal response by the kidney is to increase Cl− excretion. If the kidney fails to increase Cl− excretion appropriately, impaired renal function is at least part of the problem causing acidosis. Extrarenal causes of hyperchloremic acidosis are exogenous Cl− loads (iatrogenic acidosis) or loss of cations from the lower GI tract without proportional losses of Cl−.

Renal Tubular Acidosis

Examination of the urine and plasma electrolytes and pH and calculation of the urine apparent SID allow one to correctly diagnose most cases of renal tubular acidosis (see Figure 12-1).66 However, caution must be exercised when the plasma pH is greater than 7.35, because urinary Cl− excretion is normally decreased when pH is this high. In such circumstances, it may be necessary to infuse sodium sulfate or furosemide. These agents stimulate Cl− and K+ excretion and can be used to unmask the defect and probe K+ secretory capacity.

Iatrogenic Acidosis

Two of the most common causes of a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis are iatrogenic, and both are due to administration of Cl−. Modern parenteral nutrition formulas contain weak anions such as acetate in addition to Cl−. The proportions of each anion can be adjusted depending on the acid-base status of the patient. If an insufficient amount of weak anions is provided, the plasma Cl− concentration increases, decreasing SID and resulting in acidosis. A similar condition can arise when normal saline is used for fluid resuscitation, resulting in the development of “dilutional acidosis.” Dilutional acidosis was first described more than 40 years ago,67,68 although some authors have argued that this problem is rarely clinically significant.69 This view pertains because large doses of NaCl produce only minor degrees of hyperchloremic acidosis in healthy animals.70 This line of reasoning cannot be applied to critically ill patients, who often require infusion of a very large volume of resuscitation fluid. Furthermore, acid-base balance is often already deranged in critically ill patients, and these patients may not be able to compensate normally by increasing ventilation or may have abnormal buffer capacity due to hypoalbuminemia. In ICU and surgical patients,71–73 as well as in animals with experimental sepsis,74 saline-induced acidosis clearly occurs.

Administration of normal saline causes acidosis because this solution contains equal amounts of Na+ and Cl−, whereas the normal Na+ concentration in plasma is 35 to 45 mEq/L greater than the normal Cl− concentration. Administration of 0.9% saline increases the Cl− concentration relatively more than the Na+ concentration. Many critically ill patients have a significantly lower SID than do healthy individuals, even when there is no evidence of a metabolic acid-base derangement.75 The lower SID in critical illness is not surprising given that the positive charge of SID is balanced by the negative charges of A− and total CO2. Since many critically ill patients are hypoalbuminemic, A− tends to be reduced. Because the body defends PCO2 for other reasons, a reduction in A− leads to a reduction in SID to maintain normal pH. Thus, a typical ICU patient might have a SID of 30 mEq/L rather than 40 to 42 mEq/L. If this same patient then develops a metabolic acidosis (e.g., lactic acidosis), SID decreases further. If the patient is resuscitated with a large volume of 0.9% saline, metabolic acidosis is exacerbated. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 12-3, which shows that a patient with a lower baseline SID is more susceptible to a subsequent acid load.

One alternative to using normal saline to resuscitate patients is to use Ringer’s lactate solution. This fluid contains a more physiologic difference between [Na+] and [Cl−], so its SID is closer to normal (28 mEq/L as compared to 0 mEq/L for normal saline). Morgan and colleagues recently showed that a solution with a SID of approximately 24 mEq/L results in a neutral effect on the pH as blood is progressively diluted.76

Unexplained Hyperchloremic Acidosis

Critically ill patients sometimes manifest hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis for unclear reasons. Often these patients have other coexisting types of metabolic acidosis, making the precise diagnosis difficult. Patients with sepsis and acidosis frequently have normal circulating lactate levels.77 Often, unexplained anions are the cause,29–31 but hyperchloremic acidosis also can be a contributing factor.

Metabolic Alkalosis

Metabolic Alkalosis

Metabolic alkalosis occurs as a result of an increase in SID or a decrease in ATOT. These changes can occur secondary to the loss of anions (e.g., Cl− from the stomach, albumin from the plasma) or the retention of cations (rare). Sometimes the loss of Cl− is temporary and can be treated effectively by replacing the anion; metabolic alkalosis in this category is said to be “chloride responsive.” In other cases, hormonal mechanisms produce ongoing losses of Cl−. Thus, at best, the Cl− deficit can be offset only temporarily by Cl− administration; this form of metabolic alkalosis is said to be “chloride resistant” (Box 12-3). Similar to hyperchloremic acidosis, these disorders can be distinguished by measurement of the urine Cl− concentration.

Box 12-3

Differential Diagnosis of Metabolic Alkalosis (Increased Strong Ion Difference)

Chloride-Resistant Disorders

The chloride-resistant disorders (see Box 12-3) are characterized by an increased urine Cl− concentration (>20 mEq/L) and are said to be “chloride resistant” because of ongoing Cl− losses. Most commonly, excessive chloride excretion occurs as a result of excessive mineralocorticoid activity. Treatment requires that the underlying disorder be addressed (Table 12-2).

| Condition | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Primary aldosteronism | Spironolactone or other agents that block distal tubular sodium reabsorption improve alkalosis, hypokalemia, and hypertension. Large doses may be necessary. Restriction of sodium intake and potassium supplementation may be necessary. When an adenoma can be identified, surgery is curative. When the cause is bilateral adrenal cortical hyperplasia, therapy is medical. Dexamethasone is effective in long-term therapy of familial dexamethasone-responsive aldosteronism. |

| Secondary aldosteronism | ACE inhibitors are usually effective. Repair of the underlying lesion, if feasible, may be required. |

| Cushing’s syndrome | Due to pituitary oversecretion of ACTH: surgery or radiation. |

| Due to adrenal adenoma or carcinoma: adrenalectomy. | |

| Due to secondary or ectopic ACTH production: address the underlying malignancy. | |

| Liddle’s syndrome | Triamterene may be effective. |

| Bartter’s syndrome | Treatment often unsatisfactory long-term. Potassium-sparing diuretics, potassium and magnesium supplementation, ACE inhibitors, COX inhibitors are partially effective. |

| Exogenous corticoids | Discontinuation of the offending agent(s) and vigorous initial potassium replacement. |

| Severe potassium or magnesium depletion | Replacement of these electrolytes (may require very large amounts). |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme, COX, Cyclooxygenase.

From Spital A, Garella S. Correction of acid-base derangments. In Ronco C, Bellomo R (eds) Critical Care Nephrology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 311-328. Used with permission.

Respiratory Acid-Base Disorders

Respiratory Acid-Base Disorders

Pathophysiology of Respiratory Acid-Base Disorders

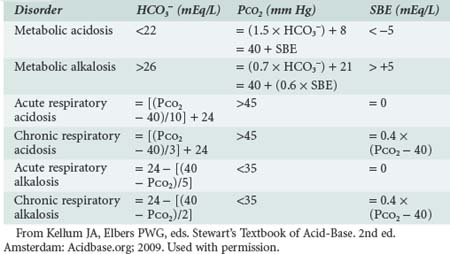

Normal CO2 production by the body (about 220 mL/min) is equivalent to 15,000 mM/day of carbonic acid.78 This amount compares to less than 500 mM/day for all nonrespiratory acids that are handled by the kidney and gut. Pulmonary ventilation is adjusted by the respiratory center in response to changes in PaCO2, blood pH, and PaO2 as well as other factors (e.g., exercise, anxiety, wakefulness). Normal PaCO2 (40 mm Hg) is maintained by precise matching of alveolar minute ventilation to metabolic CO2 production. PaCO2 changes in compensation for alterations in arterial pH produced by metabolic acidosis or alkalosis in predictable ways (Table 12-3).

Respiratory Acidosis

Diseases of Ventilatory Impairment

where R is the respiratory exchange coefficient (generally assumed to be 0.8), and PIO2 is the inspired oxygen tension (room air is approximately 150). Thus, as PaCO2 increases, the PaO2 will decrease in a predictable fashion. If the PAO2 is reduced further, there is a defect in gas exchange.

When and How to Treat

Noninvasive ventilation is another treatment option that is useful in selected patients, particularly those with normal sensorium.79 Rapid infusion of NaHCO3 in patients with respiratory acidosis can induce acute respiratory failure if alveolar ventilation is not increased to adjust for the increased CO2 load. Thus, if NaHCO3 is used, it must be administered slowly and alveolar ventilation adjusted appropriately. Furthermore, as discussed previously, NaHCO3 works by increasing the plasma [Na+]. If this is not possible or not desirable, NaHCO3 should be avoided.

Permissive Hypercapnia

In recent years, there has been increased recognition of ventilator-associated lung injury. Accordingly, a strategy designed to reduce minute ventilation and hence increase PaCO2, so-called permissive hypercapnia or controlled hypoventilation, has been increasingly employed.11 However, permissive hypercapnia is not without risks. Sedation is mandatory and the use of neuromuscular blocking agents is frequently required. Hypercapnia is associated with increased intracranial pressure and pulmonary hypertension, making this technique unusable in patients with brain injury or right ventricular dysfunction. Controversy exists as to how low to allow the pH to go. While some authors have reported good results with pH values less than 7.0,11 most authors advocate more modest pH reductions (>7.25).

Respiratory Alkalosis

Respiratory alkalosis may be the most frequently encountered acid-base disorder. It occurs in a number of pathologic conditions, including salicylate intoxication, early sepsis, hepatic failure, and hypoxic respiratory disorders. Respiratory alkalosis also occurs with pregnancy and with pain or anxiety. Hypocapnia appears to be a particularly bad prognostic indicator in patients with critical illness.80 As in acute respiratory acidosis, acute respiratory alkalosis results in a small change in [HCO3−] as dictated by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. If hypocapnia persists, the SID will begin to decrease as a result of renal Cl− reabsorption. After 2 to 3 days, the SID assumes a new, lower steady state.81 Severe alkalemia is unusual in patients with respiratory alkalosis, and management is therefore directed to the underlying cause. Typically, these mild acid-base changes are clinically more important for what they can alert the clinician to, in terms of underlying disease, than for any threat they pose to the patient. In rare cases, respiratory depression with narcotics is necessary.

Pseudorespiratory Alkalosis

The presence of arterial hypocapnia in patients with profound circulatory shock has been termed pseudorespiratory alkalosis.82 This condition can be seen when alveolar ventilation is supported, but the circulation is grossly inadequate. In such conditions, the mixed venous PCO2 is significantly elevated, but the arterial PCO2 is normal or even decreased secondary to decreased CO2 delivery to the lungs and increased pulmonary transit time. Overall CO2 clearance is markedly decreased, and there is marked tissue acidosis, usually involving both metabolic and respiratory components. The metabolic component comes from tissue hypoperfusion and hyperlactatemia. Arterial oxygen saturation also may appear to be adequate despite tissue hypoxemia. This condition is rapidly fatal unless cardiac output is rapidly corrected.

Unified Approach to the Patient with Acid-Base Imbalance

Unified Approach to the Patient with Acid-Base Imbalance

Characterizing the Disorder

As described in greater detail in recent reviews,6–7 the first step in the approach to a patient with an acid-base imbalance is to characterize the disorder. Acid-base imbalances are usually recognized by abnormalities in the venous plasma electrolyte concentrations, so it is useful to start there. Measurement of venous [HCO3−] is the easiest way to screen for acid-base disorders. However, a normal [HCO3−] does not exclude the possibility of an acid-base derangement, even a serious one. Therefore, if the history and physical examination findings lead one to suspect a disease process that results in an acid-base imbalance, more investigation is required. The normal [HCO3−] is 22 to 26 mEq/L. Increases in [HCO3−] occur with primary and compensatory metabolic alkaloses and decreases occur with primary or compensatory metabolic acidoses. Unfortunately, in mixed disorders, [HCO3−] may be misleading, and the presence of any abnormality in [HCO3−] requires further investigation. In addition to examining the [HCO3−], venous blood can be used to calculate AG: ([Na+] + [K+]) − ([Cl−] − [HCO3−]). If [HCO3−] or AG are abnormal or if there is clinical suspicion for a mixed disorder, arterial blood should be sampled for blood gas analysis. This test will provide information on the pH, PaCO2, and standard base-excess. Although simple disorders will conform to the equations presented in Table 12-3, “mixed” disorders are quite common.

Determining the Cause

Once the disorder has been characterized, the clinician must integrate the information obtained from the history and physical examination to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Mixed disorders continue to be problematic, as any acid-base disorder that fails to fit into the classification scheme shown in Table 12-2 can be considered a mixed disorder, but some mixed disorders appear to be simple disorders when first encountered. For example, a patient with chronic respiratory acidosis and a PaCO2 of 60 mm Hg would be expected to have a standard base-excess of +8 mEq/L (see Table 12-3). If this patient develops a metabolic acidosis, the standard base-excess will decrease and may be 0 mEq/L. At this point, it may appear that the patient has a pure acute respiratory acidosis rather than a mixed disorder. If the metabolic acidosis causes an increase in AG, this abnormality may provide a clue. Another useful method is to obtain at least two blood gas analyses to examine for trends. In general, however, it is only by careful attention to history and physical examination that the true diagnosis can be made.

Kellum JA, Elbers PWG, editors. Stewart’s Textbook of Acid-Base, 2nd ed, Amsterdam: Acidbase.org, 2009.

Kellum JA. Disorders of acid-base balance. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(11):2630-2636.

A case-based review of acid-base using modern methods.

Forsythe SM, Schmidt GA. Sodium bicarbonate for the treatment of lactic acidosis. Chest. 2000;117(1):260-267.

A systematic review of the evidence for and against use of sodium bicarbonate for lactic acidosis.

Morgan TJ, Venkatesh B, Hall J. Crystalloid strong ion difference determines metabolic acid-base change during in vitro hemodilution. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):157-160.

1 Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Kramer DJ, et al. Splanchnic buffering of metabolic acid during early endotoxemia. J Crit Care. 1997;12:7-12.

2 Schlichtig R, Grogono AW, Severinghaus JW. Human PaCO2 and standard base excess compensation for acid-base imbalance. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1173-1179.

3 Corey HE. Stewart and beyond: New models of acid-base balance. Kidney Int. 2003;64:777-787.

4 Wooten EW. Calculation of physiological acid-base parameters in multicompartment systems with application to human blood. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2333-2344.

5 Stewart P. Modern quantitative acid-base chemistry. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;61:1444-1461.

6 Kellum JA, Elbers PWG, editors. Stewart’s Textbook of Acid-Base, 2nd ed, Amsterdam: Acidbase.org, 2009.

7 Kellum JA. Disorders of acid-base balance. Crit Care Med. 2007 Nov;35(11):2630-2636.

8 Bourke E, Haussinger D. pH homeostasis: The conceptual change. Contrib Nephrol. 1992;100:58-88.

9 Oliver J, Bourke E. Adaptations in urea and ammonium excretion in metabolic acidosis in the rat: A reinterpretation. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1975;48:515-520.

10 Moore EW. The alkaline tide. Gastroenterology. 1967;52:1052-1054.

11 Hickling KG, Walsh J, Henderson S, Jackson R. Low mortality rate in adult respiratory distress syndrome using low-volume, pressure-limited ventilation with permissive hypercapnia: A prospective study. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1568-1578.

12 Forsythe SM, Schmidt GA. Sodium bicarbonate for the treatment of lactic acidosis. Chest. 2000;117:260-267.

13 Kette F, Weil MH, Gazmuri RJ. Buffer solutions may compromise cardiac resuscitation by reducing coronary perfusion pressure. JAMA. 1991;266:2121-2126.

14 Hindman BJ. Sodium bicarbonate in the treatment of subtypes of lactic acidosis: Physiologic considerations. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:1064-1076.

15 Bleich HL, Swartz WB. Tris Buffer (THAM): An appraisal of its physiologic effects and clinical usefulness. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:782-787.

16 Arieff AI. Bicarbonate therapy in the treatment of metabolic acidosis. In: Chernow B, editor. The Pharmacologic Approach to the Critically Ill Patient. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:973.

17 Narins RG, Emmett M. Simple and mixed acid-base disorders: A practical approach. Medicine. 1980;59:161-187.

18 Figge J, Mydosh T, Fencl V. Serum proteins and acid-base equilibria: a follow-up. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:713-719.

19 Sadjadi SA. A new range for the anion gap. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:807.

20 Winter SD, Pearson R, Gabow PG, et al. The fall of the serum anion gap. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:311-313.

21 Levinsky NG. Acidosis and alkalosis. In Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Petersdorf RG, et al, editors: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 11th ed, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987.

22 Salem MM, Mujais SK. Gaps in the anion gap. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1625-1629.

23 Oster JR, Perez GO, Materson BJ. Use of the anion gap in clinical medicine. South Med J. 1988;81:229-237.

24 Gabow PA. Disorders associated with an altered anion gap. Kidney Int. 1985;27:472-483.

25 Whelton A, Carter GG, Garth M, et al. Carbenicillin-induced acidosis and seizures. JAMA. 1971;218:1942.

26 Kang Y, Aggarwal S, Virji M, et al. Clinical evaluation of autotransfusion during liver transplantation. Anesth Analg. 1991;72:94-100.

27 Narins RG, Jones ER, Townsend R, et al. Metabolic acid-base disorders: Pathophysiology, classification and treatment. In: Arieff AI, DeFronzo RA, editors. Fluid Electrolyte and Acid-Base Disorders. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1985:269-385.

28 Arieff AI, Carroll HJ. Nonketotic hyperosmolar coma with hyperglycemia: Clinical features, pathophysiology, renal function, acid-base balance, plasma-cerebro spinal fluid equilibria and effects of therapy in 37 cases. Medicine. 1972;51:73.

29 Mecher C, Rackow EC, Astiz ME, Weil MH. Unaccounted for anion in metabolic acidosis during severe sepsis in humans. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:705-711.

30 Gilfix BM, Bique M, Magder S. A physical chemical approach to the analysis of acid-base balance in the clinical setting. J Crit Care. 1993;8:187-197.

31 Kellum JA, Kramer DJ, Pinsky MR. Strong ion gap: A methodology for exploring unexplained anions. J Crit Care. 1995;10:51-55.

32 Kirschbaum B. Increased anion gap after liver transplantation. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313:107-110.

33 Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Kramer DJ, Pinsky MR. Hepatic anion flux during acute endotoxemia. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:2212-2217.

34 Mehta K, Kruse JA, Carlson RW. The relationship between anion gap and elevated lactate. Crit Care Med. 1986;14:405-414.

35 Schlichtig R. [Base excess] vs [strong ion difference]: Which is more helpful? Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;411:91-96.

36 Mizock BA, Falk JL. Lactic acidosis in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:80-93.

37 Weil MH, Afifi AA. Experimental and clinical studies on lactate and pyruvate as indicators of the severity of acute circulatory failure (shock). Circulation. 1970;41:989-1001.

38 Blair E. Acid-base balance in bacteremic shock. Arch Intern Med. 1971;127:731-739.

39 Madias NE. Lactic acidosis. Kidney Int. 1986;29:752-774.

40 Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Pinsky MR. Visceral lactate fluxes during early endotoxemia in the dog. Chest. 1996;110:198-204.

41 van Lambalgen AA, Runge HC, van den Bos GC, Thijs LG. Regional lactate production in early canine endotoxin shock. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:E45-E51.

42 Cain SM, Curtis SE. Systemic and regional oxygen uptake and delivery and lactate flux in endotoxic dogs infused with dopexamine. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:1552-1560.

43 Brown S, Gutierrez G, Clark C, et al. The lung as a source of lactate in sepsis and ARDS. J Crit Care. 1996;11:2-8.

44 Kellum JA, Kramer DJ, Lee KH, et al. Release of lactate by the lung in acute lung injury. Chest. 1997;111:1301-1305.

45 De Backer D, Creteur J, Zhang H, et al. Lactate production by the lungs in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1099-1104.

46 Stacpoole PW. Lactic acidosis and other mitochondrial disorders. Metab Clin Exp. 1997;46:306-321.

47 Fink MP. Does tissue acidosis in sepsis indicate tissue hypoperfusion? Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:1144-1146.

48 Gutierrez G, Wolf ME. Lactic acidosis in sepsis: A commentary. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:6-16.

49 Kilpatrick-Smith L, Dean J, Erecinska M, Silver IA. Cellular effects of endotoxin in vitro. II. Reversibility of endotoxic damage. Circ Shock. 1983;11:101-111.

50 Gore DC, Jahoor F, Hibbert JM, DeMaria EJ. Lactic acidosis during sepsis is related to increased pyruvate production, not deficits in tissue oxygen availability. Ann Surg. 1996;224:97-102.

51 Bearn AG, Billing B, Sherlock S. The effect of adrenaline and noradrenaline on hepatic blood flow and splanchnic carbohydrate metabolism in man. J Physiol. 1951;115:430-441.

52 Levy B, Bollaert P-E, Charpentier C, et al. Comparison of norepinephrine and dobutamine to epinephrine for hemodynamics, lactate metabolism, and gastric tonometric variables in septic shock: A prospective randomized study. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:282-287.

53 Zilva JF. The origin of acidosis in hyperlactatemia. Ann Clin Biochem. 1978;15:40-43.

54 Madias NE, Homer SM, Johns CA, Cohen JJ. Hypochloremia as a consequence of anion gap metabolic acidosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104:15-23.

55 Cohen RD, Woods HF. Lactic acidosis revisited. Diabetes. 1983;32:181-191.

56 Kreisberg RA. Lactate homeostasis and lactic acidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:227-237.

57 Alberti KGMM. Diabetic emergencies. Br Med J. 1989;45:242-263.

58 Magder S. Pathophysiology of metabolic acid-base disturbances in patients with critical illness. In: Ronco C, Bellomo R, editors. Critical Care Nephrology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998:279-296.

59 Bakerman S. ABC’s of Interpretive Laboratory Data. Greenville, NC: Interpretive Laboratory Data Inc.; 1984. p. 3

60 Androque HJ, Tannen RL. Ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar states, and lactic acidosis. In: Kokko JP, Tannen RL, editors. Fluids and Electrolytes. Philadelphia: WB. Saunders; 1996:643-674.

61 Good DG. Regulation of bicarbonate and ammonium absorption in the thick ascending limb of the rat. Kidney Int. 1991;40:S36-S42.

62 Fulop M. Alcoholic ketoacidosis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1993;22:209-219.

63 Wrenn KD, Slovis CM, Minion GE, Rutkowski R. The syndrome of alcoholic ketoacidosis. Am J Med. 1991;91:119-128.

64 Widmer B, Gerhardt RE, Harrington JT, Cohen JJ. Serum electrolyte and acid base composition: The influence of graded degrees of chronic renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139:1099.

65 Harrington JT, Cohen JJ. Metabolic acidosis. In: Cohen JJ, Kassirer JP, editors. Acid-Base. Boston: Little, Brown and Co; 1982:121-225.

66 Battle DC, Hizon M, Cohen E, et al. The use of the urine anion gap in the diagnosis of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:594.

67 Cheek DB. Changes in total chloride and acid-base balance in gastroenteritis following treatment with large and small loads of sodium chloride. Pediatrics. 1956;17:839-847.

68 Shires GT, Tolman J. Dilutional acidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1948;28:557-559.

69 Garella S, Chang BS, Kahn SI. Dilution acidosis and contraction alkalosis: Review of a concept. Kidney Int. 1975;8:279-283.

70 Garella S, Tzamaloukas AH, Chazan JA. Effect of isotonic volume expansion on extracellular bicarbonate stores in normal dogs. Am J Physiol. 1973;225:628-636.

71 Waters JH, Bernstein CA. Dilutional acidosis following hetastarch or albumin in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1184-1187.

72 Waters JH, Miller LR, Clack S, et al. Cause of metabolic acidosis in prolonged surgery. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2142-2146.

73 Wilkes NJ, Woolf R, Mutch M, et al. The effects of balanced versus saline-based hetastarch and crystalloid solutions on acid-base and electrolyte status and gastric mucosal perfusion in elderly surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:811-816.

74 Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Kramer DJ, et al. Etiology of metabolic acidosis during saline resuscitation in endotoxemia. Shock. 1998;9:364-368.

75 Kellum JA. Recent advances in acid-base physiology applied to critical care. In: Vincent JL, editor. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1998:577-587.

76 Morgan TJ, Venkatesh B, Hall J. Crystalloid strong ion difference determines metabolic acid-base change during in vitro hemodilution. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:157-160.

77 Gilbert EM, Haupt MT, Mandanas RY, et al. The effect of fluid loading, blood transfusion, and catecholamine infusion on oxygen delivery and consumption in patients with sepsis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:873-878.

78 Gattinoni L, Lissoni A. Respiratory acid-base disturbances in patients with critical illness. In: Ronco C, Bellomo R, editors. Critical Care Nephrology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998:297-312.

79 Brochard L, et al. Noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:817-822.

80 Gennari FJ, Kassirer JP. Respiratory alkalosis. In: Cohen JJ, Kassirer JP, editors. Acid-Base. Boston: Little, Brown and Co; 1982:349-376.

81 Cohen JJ, Madias NE, Wolf CJ, Schwartz WB. Regulation of acid-base equilibrium in chronic hypocapnia: Evidence that the response of the kidney is not geared to the defense of extracellular [H+]. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:1483-1489.

82 Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Management of life-threatening acid-base disorders: Part II. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:107-111.