Acid–base

concepts and vocabulary

H+ concentration

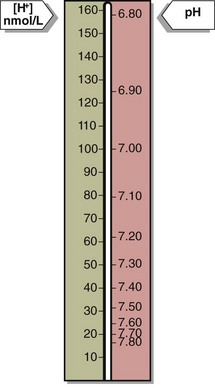

Blood hydrogen ion concentration [H+] is maintained within tight limits in health. Normal levels lie between 35 and 45 nmol/L. Values greater than 120 nmol/L or less than 20 nmol/L require urgent treatment; if sustained they are usually incompatible with life. The [H+] in blood may also be expressed in pH units. pH is defined as the negative log of the hydrogen ion concentration. (Fig 20.1).

H+ excretion in the kidney

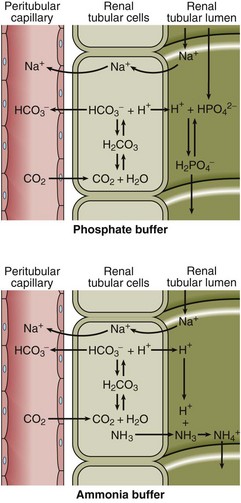

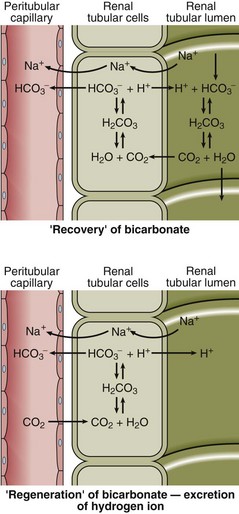

All the H+ that is buffered must eventually be excreted from the body via the kidneys, regenerating the bicarbonate used up in the buffering process and maintaining the plasma bicarbonate concentration within normal limits (Fig 20.2). Secretion of H+ by the tubular cells serves initially to reclaim bicarbonate from the glomerular filtrate so that it is not lost from the body. When all the bicarbonate has been recovered, any deficit due to the buffering process is regenerated. The mechanisms for bicarbonate recovery and for bicarbonate regeneration are very similar and are sometimes confused (Fig 20.2).

Fig 20.2 The recovery and regeneration of bicarbonate by excretion of H+ in the renal tubular cell. Note that H+ is actively secreted into the urine while CO2 diffuses along its concentration gradient.

The excreted H+ must be buffered in urine or the [H+] would rise to very high levels. Phosphate acts as one such buffer, while ammonia is another (Fig 20.3).

Assessing status

where K is the first dissociation constant of carbonic acid.

which shows that the H+ concentration in blood varies as the bicarbonate concentration and PCO2 change. If everything else remains constant:

Adding H+, removing bicarbonate or increasing the PCO2 will all have the same effect; that is, an increase in [H+].

Adding H+, removing bicarbonate or increasing the PCO2 will all have the same effect; that is, an increase in [H+].

Removing H+, adding bicarbonate or lowering PCO2 will all cause the [H+] to fall.

Removing H+, adding bicarbonate or lowering PCO2 will all cause the [H+] to fall.

Blood [H+] is controlled by our normal pattern of respiration and the functioning of our kidneys.