Chapter 26 Achieving Functional Independence

Functional independence is the ability to perform daily living tasks without help. The achievement of functional independence ensures that individuals can participate fully in life situations that are meaningful and purposeful. Whether experiencing a physical disability or not, participation in activities of daily living or life occupations is essential to health and well-being.3 Anthropologists have noted that involvement in the daily routines of self-maintenance, production, and leisure enables humans to express themselves, establish relationships, and build self-identity.5 The World Health Organization has recognized the importance of participation in life situations to health by reframing the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps31 as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.30 In doing this, understandings of health have shifted significantly from definitions relating to the absence of disease or impairment. This embraces the notion of an individual engaging with and functioning in her or his world even with the presence of a disability and physical challenges. Supporting this shift is emerging evidence of the powerful therapeutic benefit of participation in meaningful daily occupations.5 Individuals who are able to achieve meaningful participation in life situations are more likely to experience and report increased personal satisfaction and quality of life, increased levels of energy, fewer physical ailments, reduced pain, and improved physical functioning.17 Ultimately, this impact can decrease the costs of health associated with burden of care, the treatment of physical symptomatology, and poor emotional health.

The goal of medical rehabilitation programs for persons experiencing physical disability as a result of injury, illness, or a developmental condition is to maximize functional independence over time.7 All members of the rehabilitation team are focused on restoring or enhancing functional capacity such that individuals can engage optimally in daily life tasks that are meaningful and purposeful. Because of the subjective nature of what constitutes “meaningful” and “purposeful,” it is important to adopt a family- or client-centered frame of reference for care. This frame of reference defines a set of philosophies, attitudes, and approaches to care for persons with special needs and their families.8 It refers to a relationship between the person, family, and health care professional that builds on the person’s and family’s priorities and that responds to their mutual goals.4 Some key elements in family- or client-centered care include recognizing family strengths, respecting different methods of coping, facilitating family and professional collaboration at all levels of health care, and sharing complete and unbiased information with families on a continuing basis and in a supportive manner. By adopting this frame of reference in practice, the rehabilitation team will be able to plan an evaluation and treatment process that matches the individual’s life goals and priorities. Rehabilitation programs that focus their interventions in this way are more likely to achieve the desired outcomes of enhancing productive living, promoting efficient recovery, and reducing the burden of care for individuals with physical disabilities over the long term.10,16,26

Evaluation

Using a family- or client-centered approach, evaluation of an individual’s functional independence necessarily begins with the determination of that person’s life goals, premorbid roles and activities, priorities for recovery, and contextual or cultural influences. From here, a more specific assessment can be conducted that evaluates the individual’s actual performance abilities and limitations in key areas of function. It also measures components of functional skill, including strength, range of motion, tone, sensation, balance, coordination, visual perception, and cognition. This type of evaluation process is referred to as the top-down approach and is considered “the best fit for the emerging system of health-care delivery.”14 The top-down approach has the advantage of focusing clearly on the roles and activities that are meaningful for patients, which increases motivation for participation in the rehabilitation process and increases the understanding of the relevance of rehabilitation to daily life. The top-down evaluation approach also allows for documentation of outcomes of rehabilitation in terms that are most likely to receive maximum reimbursement. Payers specifically seek outcomes of therapy that allow the patient to function most efficiently and effectively in daily contexts.14 Top-down evaluation results in the medical team addressing rehabilitation goals that are directly related to the individual’s performance in life roles.

Evaluating Meaningful Life Roles and Activities

Assessment of a person’s life goals, valued functional roles and activities, and priorities for recovery is a complex one. Because of the subjective nature of the content, there are few evaluation tools that provide the rehabilitation team with succinct, quantifiable data relating to this issue. Information about the person’s priorities and premorbid activity is usually gained through discussion and interview with the person and/or caregivers. It is important that those team members charged with the responsibility of gathering this information are skilled in techniques of interviewing and counseling to ensure that the individual is able to clearly communicate personal needs and wants.

Within the field of occupational therapy, an evaluation tool has been developed specifically for the purpose of assisting occupational therapists to establish occupational performance (functional performance) goals and priorities with their clients. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)18 was developed using a client-centered frame of reference and consists of a semistructured interview approach for gathering patients’ perspectives on their needs and wants in areas of self-care, productive living, and leisure. The evaluation process encourages patients to rate their perceptions of their current levels of performance and satisfaction with participation in key functional tasks. These are then reevaluated and rerated at the end of the rehabilitative process to provide outcome data relating to the patient’s perspective on recovery. Evaluation tools such as the COPM provide broad, descriptive information about the person’s functional independence needs, which allows the rehabilitation team to target specific areas requiring further evaluation and focus in treatment.

Evaluating Specific Performance Abilities

Once the patient’s valued life roles and activities have been identified and goals for rehabilitation determined, more specific evaluations are then completed to establish what performance limitations and abilities exist. A variety of methods can be used to assess functional skills. In many cases, therapists use guided observation and task analysis to determine the level of functional independence demonstrated by the patient. A number of formal measures have been developed for the purpose of measuring functional capacity. The most commonly used tool in this area is the functional independence measure (FIM).2 The FIM consists of 18 items examining the functional areas of self-care, sphincter control, transfers, locomotion, communication, and social cognition. Scores on the FIM provide an indicator of level of disability within motor and cognitive domains based on the level of assistance a patient requires to perform key functional tasks.21 A pediatric version of the FIM, the WeeFIM,1 has been developed for children aged 6 months to 7 years. It uses a similar structure to the FIM but modifies the items to account for developmental differences in social cognition and communication domains. Data from the FIM and the WeeFIM are being compiled in the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation to provide a repository of information regarding the functional independence of adults and children experiencing physical disability. Other tools used in rehabilitation settings to measure the functional abilities of patients include the following:

Evaluation of Components of Performance

Treatment

A number of treatment approaches can be used to assist an individual experiencing physical disability to achieve functional independence. The treatment approach chosen by the therapist and team depends on the specific goals set by the individual, the degree of functional limitation experienced, and the type and severity of the component skill impairments noted. Multiple treatment approaches can be used simultaneously with an individual to address different goals. Treatment approaches can generally be understood to fall into two main categories: restorative or compensatory.14 The goal of a restorative or facilitatory treatment approach is to restore the person’s capacity to perform functional skills by restoring the impaired component skills. The aim of this approach is to retrain the individual to perform functional tasks in the same way as was done premorbidly. It is an appropriate treatment strategy when complete or close to complete recovery is expected and few environmental or contextual barriers to functional independence exist. A number of frames of reference for intervention can be adopted depending on the impairments experienced by the individual. The most common frames of reference used in physical rehabilitation are as follows:

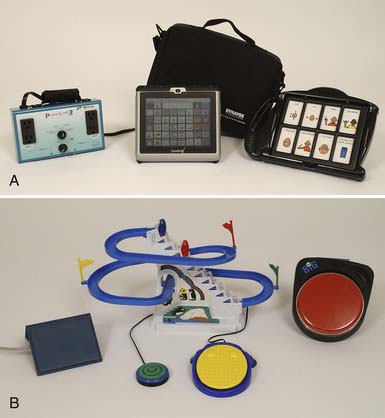

With the enormous progress made in recent years in technology, individuals with physical disabilities are now able to achieve much higher levels of functional independence than was previously possible through the use of technologic aids. The area of assistive technology is a dedicated field within rehabilitation that specializes in fitting individuals with physical and cognitive disabilities with both low- and high-tech solutions to enhance mobility, communication, community access, and learning. The application of assistive technology in physical disability is discussed in Chapters 17 and 23 of this text.

Self-Maintenance

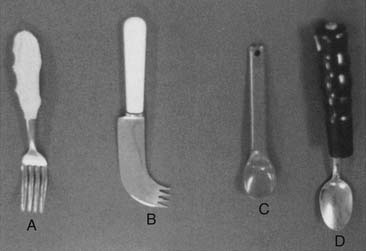

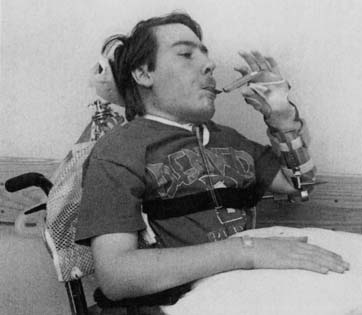

Feeding

Dressing

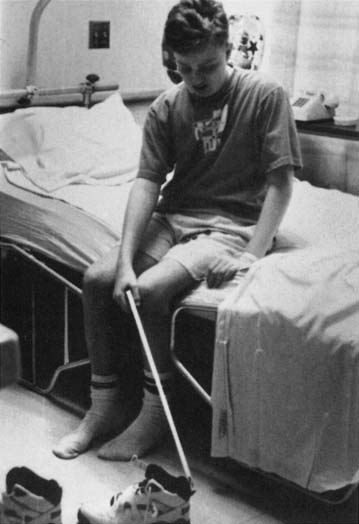

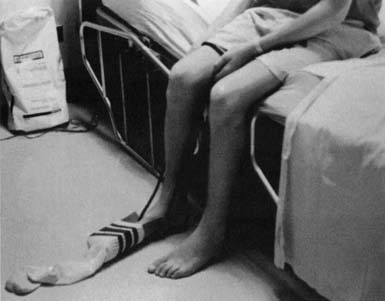

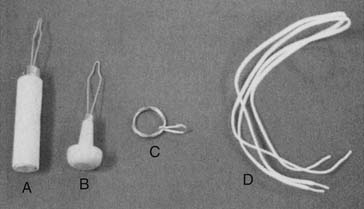

Treatment techniques incorporate both restorative and compensatory approaches. Substantial gains can be made toward independence through the use of simple compensatory techniques. For example, one-handed dressing techniques that require neither caregiver assistance nor adaptive equipment can be taught to an individual with hemiplegia. The careful selection of clothing, such as avoiding complex fasteners, can also promote increased independence. Modified clothing is now commercially available; however, homemade modifications can also be effective. For example, when hand strength is limited, putting loops on socks is useful to assist in pulling them up. Velcro fasteners on pants can facilitate toileting. In the case of perceptual or cognitive problems, labeling clothes helps the person distinguish front from back. Adaptive equipment commonly used to facilitate independence in dressing includes the following:

FIGURE 26-5 Fastener adaptations: button aid (A), knob handle button aid (B), zipper pull (C), and elastic laces (D).

Bathing and Grooming

In a similar fashion to dressing, achieving independence in bathing and grooming significantly decreases the physical and time burden on caregivers of individuals with disabilities. This also helps to maintain the individual’s sense of dignity and privacy. The bathroom can be a safety risk area for an individual with significant physical or cognitive disability. To gain independence in this environment, the individual must be able to safely negotiate slippery floors and small spaces and use safety strategies around use of various temperatures of water. Within the area of bathing and grooming, treatment focuses on the development of:

Restorative treatment approaches can be used to promote physical skill competence. Compensatory techniques such as task and environmental modifications are most likely to be used to optimize the independence of the individual with physical and cognitive impairments to promote bathroom safety (e.g., turning down the temperature on the home hot water system to minimize scalds). Major bathroom renovation is often necessary to achieve independence in bathing and grooming for an individual using a wheelchair for ambulation (Figure 26-8). Adaptive equipment commonly used to facilitate independence in grooming includes the following:

Hygiene and Health Routine Maintenance

Functional Mobility

Bed Mobility

Transfers

Some of the more common methods of performing transfers are described below:

Ambulation

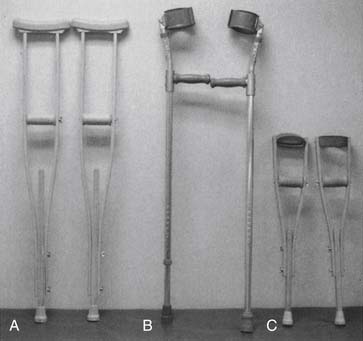

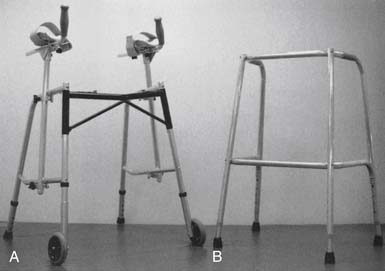

Independent ambulation is not time or energy efficient in some cases, and the use of orthoses and other adaptive equipment might be required (lower limb orthoses are discussed in detail in Chapter 16 of this text). Commonly used walking aids include the following:

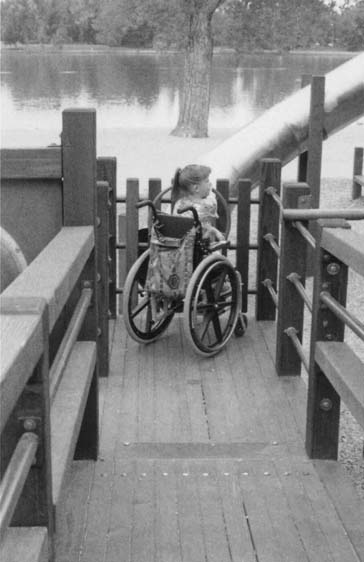

Wheelchair Mobility

For people who are unable to ambulate or are able to ambulate only short distances, the use of a wheelchair for mobility can allow increased functional independence in the community. The process for evaluating and prescribing a wheelchair for an individual with a disability is described in detail in Chapter 17 of this text. Many factors affect the type of chair prescribed, including many aspects of the individual’s skills and abilities, the contexts in which the chair will be used, transportation options, and the availability of maintenance support.29 After the wheelchair is prescribed, a period of training might be required to fully develop the individual’s skills in independent use. With the variety of technologies currently available in manual and power wheelchairs, it is now possible for individuals with high degrees of physical disability to independently mobilize in a wheelchair.

Driving

Being able to drive or be transported in a private vehicle is often an identified priority for individuals with disabilities and their families. Achieving this level of independence in mobility means that individuals have access to a broader range of productive and leisure activities. Individuals can then easily attend social occasions, participate in vacations, and complete routine daily errands. A compensatory approach is most commonly used to address issues of independence in driving or traveling in a private vehicle. For self-driving, careful evaluation of residual physical and cognitive skills will determine the level of accommodation needed in car controls and operation. Commonly used car adaptations include the following23:

Productive Activity

Paid or Volunteer Work

Participation in productive activity via paid or volunteer work can be important to individuals for a number of reasons. It might allow them to be self-sufficient financially; acquire a sense of self-esteem, social status, and group membership; and add structure and routine to their daily lives.11 Issues surrounding the employment of people with disabilities are discussed in more detail in another chapter of this text. In general, however, to optimize the achievement of functional independence in this area it will require consideration of:

Household Management

Household management is an important aspect of maintaining daily routines and for many adults represents their primary source of productive activity. Assisting an individual to gain functional independence in this area can promote a sense of role identity lost because of illness or injury. Restoring the motor skills required for home maintenance tasks might not be possible or sufficient to ensure full independence in many cases. Integral to successful household management is the combination of motor proficiency (particularly upper limb proficiency) with planning, organization, safety awareness, and money management skills.6,11 Most commonly, a compensatory approach is required. This generally takes two forms. First, the physical setup of the home has to be considered in relation to whether it supports access of the individual to all areas of the home to perform cleaning, laundry, yard maintenance, and meal preparation tasks. Second, tasks performed have to be analyzed and modified as necessary to conserve energy and allow independent completion despite physical or cognitive limitations.6 Clear and open communication with the individual is essential in this process to identify priority household tasks for completion because home routines are highly individualized and value based. Commonly used adaptations and modifications that enhance independent household management include the following:

Play and School

FIGURE 26-15 Positioning devices. (A) Customized seating system. (B) Foam wedges.

(Courtesy The Children’s Hospital, Aurora, CO.)

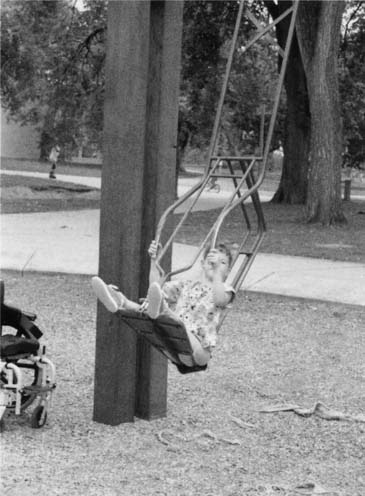

FIGURE 26-17 An adapted swing. The movement of the swing is achieved by pushing or pulling on the handles, using the arms.

Leisure

Time spent in leisure and recreation is considered essential to an individual’s psychologic well-being.5 Leisure activity is activity participated in for its own sake and where enjoyment is the primary goal. The authors believe that leisure is important for self-expression, creativity, relaxation, belongingness, and experience of novelty.27 Meaningful participation in leisure activities by people with disabilities is highly motivating and can also facilitate the achievement of independence in other areas such as community integration, self-maintenance, mobility, and organizational and problem-solving skills. The rehabilitation team should consider leisure as both a means and an end in terms of the achievement of functional independence.24 Leisure can take a number of forms and can include quiet recreational activities such as hobbies or crafts or more active recreation such as sports and travel. Many organizations now exist to facilitate the inclusion of people with disabilities into recreational activities. For example, some communities have established programs specifically designed for people with physical and cognitive disabilities that are run within community recreation centers. Various advocacy groups and foundations sponsor camping and sports programs for individuals with brain injuries, burns, or chronic conditions. In recent years, more attention has been focused on competitive sports participation by people with disabilities. This is available at local, national, and international levels, culminating in events such as the Paralympics. As in other areas of functional independence, consideration must be given to the interests, priorities, and available resources of individuals and their families; individuals’ specific motor and cognitive skills and limitations; and the potential for adaptation of the activity before planning interventions relating to leisure participation. Figures 26-20 through 26-24 show examples of adaptations made to common leisure pursuits, enabling people with disabilities to experience enjoyment and achievement.

Conclusion

Assisting an individual to achieve optimal functional independence should be the goal of all medical rehabilitation programs. The benefits to individuals and their families or caregivers are clear. For the individual, an increased sense of personal satisfaction, self-worth, and self-actualization are all coupled with decreased physical ailments and increased vitality. For caregivers, the physical and emotional burden of care associated with physical disability can be reduced or minimized. For rehabilitation programs, a focus on improving outcomes related to functional independence translates into an increased likelihood of reimbursement and enhanced patient satisfaction. A number of possible approaches can be used to facilitate functional independence in persons with disabilities that are typically either restorative or compensatory in focus. As further advances in technology are made, opportunities for individuals with significant levels of disability will emerge to allow them to participate fully in their life Situations.

1. [Anonymous]. Functional independence measure for children (WeeFIM). Outpatient version 1.0. Buffalo: State University of New York, Buffalo, NY; 1994.

2. [Anonymous]. Guide for the uniform data set for medical rehabilitation (adult FIM). Version 4.0. Buffalo: State University of New York at Buffalo; 1993.

3. Baum M.C. Participation: its relationship to occupation and health. OTJR: Occup Participation Health. 2003;23(2):46-47.

4. Breske S. When it comes to rehabilitation, family matters. Adv Phys Ther. 1992;23:4.

5. Christiansen C., Baum C. Understanding occupation: definitions and concepts. In Christiansen C., Baum C., editors: Occupational therapy: enabling function and well-being, ed 2, Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1997.

6. Culler K.H. Home management. In: Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Schell B.A.B., editors. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

7. Dittmar S.S. Overview: a functional approach to measurement of rehabilitation outcomes. In: Dittmar S.S., Gresham G.E., editors. Functional assessment and outcome measures for the rehabilitation health professional. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1997.

8. Edelman L. Getting on board: training activities to promote the practice of family-centered care. Bethesda, Md: Association for the Care of Children’s Health; 1991.

9. Fisher A. Assessment of motor and process skills. Report no.: research edition 7.0. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University; 1994.

10. Fisher A. The foundation: functional measures. 2. Selecting the right test, minimizing the limitations. Am J Occup Ther. 1992;46(3):278-281.

11. Foster M. Life skills. In: Turner A., Foster M., Johnson S.E., editors. Occupational therapy and physical dysfunction. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

12. Foster M. Theoretical frameworks. In: Turner A., Foster M., Johnson S.E., editors. Occupational therapy and physical dysfunction. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

13. Hayley S.M., Coster W.J., Fass R.M. A content validity study of the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. Pediatr Phys Ther. 1991;3:177-184.

14. Holm M.B., Rogers J.C., Stone R.G. Person–task–environment interventions: a decision-making guide. In Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Schell B.A.B., editors: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 10, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

15. Iyer M.B., Pedretti L. Evaluation of sensation and treatment of sensory dysfunction. In Pedretti L., Early M., editors: Occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, 10th edn., St. Louis: Mosby, 2001.

16. Johnson M.V., Maney M., Wilkerson D.L. Systematically assuring and improving the quality and outcomes of medical rehabilitation programs. In DeLisa J.A., Gans B.M., editors: Rehabilitation medicine: principles and practice, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998.

17. Larson E., Wood W., Clark F. Occupational science: building the science and practice of occupation through an academic discipline. In Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Schell B.A.B., editors: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 10, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

18. Law M., Baptiste S., McColl M.A., et al. The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1990;57:82-87.

19. Mahoney F., Barthel D.W. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65.

20. Nawoczenski D.A., Rinehart M.E., Duncanson P., et al. Physical management. In: Buchanan L.E., Nawoczenski D.A., editors. Spinal cord injury: concepts and management approaches. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1987.

21. Ottenbacher K.J., Christiansen C. Occupational performance assessment. In Christiansen C., Baum C., editors: Occupational therapy: enabling function and well-being, ed 2, Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1997.

22. Pedretti L. Muscle strength. In Pedretti L., Early M., editors: Occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 10, St. Louis: Mosby, 2001.

23. Pierce S. Restoring competence in mobility. In Trombly C., Radomski M., editors: Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction, ed 5, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

24. Primeau L.A. Play and leisure. In Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Schell B.A.B., editors: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 10, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

25. Roberts S.D., Wells R.D., Brown I.S., et al. The FRESNO: a pediatric functional outcome measurement system. J Rehabil Outcomes Meas. 1999;3(1):11-19.

26. Robertson S.C., Colborn A.P. Outcomes research for rehabilitation: issues and solutions. J Rehabil Outcomes Meas. 1997;1:15-23.

27. Tinsley H.E., Eldredge B.D. Psychological benefits of leisure participation. A taxonomy of leisure activities based on their need gratifying properties. J Couns Psychol. 1995;42(2):123-132.

28. Wheatley C.J. Evaluation and treatment of perceptual motor deficits. In Pedretti L., Early M., editors: Occupational therapy: practice skills for physical dysfunction, ed 5, St. Louis: Mosby, 2001.

29. White E. Aids to mobility. In Turner A., Foster M., Johnson S.E., editors: Occupational therapy and physical dysfunction, ed 5, Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

30. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

31. World Health Organization. International classification of impairments, disabilities, and handicaps: a manual of classification relating to the consequences of disease. Geneva: WHO; 1980.