Chapter 56 Acetabular Fractures: Does Delay to Surgery Infl uence Outcome?

Fractures of the acetabulum can be devastating injuries often associated with high-energy trauma. Patient outcome is adversely affected by many factors, some of which cannot be influenced by the treating surgeon. These include age, osteoporosis, obesity, and associated injuries. The fracture pattern and severity, as well as specific prognostic features such as marginal impaction and femoral head damage are also outside of the surgeon’s control. However, the surgeon is able to influence factors such as the timing of surgery, choice of approach, accuracy of reduction, and the maintenance of that reduction.1,2

Historically, acetabular fractures were treated with traction and other nonoperative techniques. However, modern treatment now involves operative reduction and fixation of the acetabulum in most cases.3 Acetabular fractures are classified as either elementary fractures involving one fracture line or associated fractures involving multiple fracture elements.4,5 Anatomic reduction has been consistently identified as an important prognostic indicator of a good clinical outcome in acetabular fractures.5–11

Acetabular fracture surgery is demanding and requires a specialized surgeon and team (Level V). Surgical treatment strategies often involve partial fracture exposure and reduction via indirect means because of anatomic constraints of the pelvis. These indirect reduction strategies rely on mobility between the fracture fragments especially when treating associated fracture types. As the fracture begins to heal, organized hematoma and callus can interfere with fracture mobility. This decreased mobility makes anatomic reduction difficult, allowing imperfect reductions to become more prevalent.9,10, 12 A strategy to deal with decreased fracture mobility involves the use of more direct fracture reduction techniques; however, this often requires multiple or extensile exposures with their associated morbidity.13–15

The reasons for delay to treatment can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, the patient’s traumatic or medical comorbidities may necessitate a delay until the patient is suitable for prolonged surgery. Availability of specialized surgeons and surgical resources can also be a cause for delay. In some medical systems, shortage of hospital bed resources can significantly delay transfer to specialized centers.16 Few surgeons will argue that treatment of these injuries should be excessively delayed. The purpose of this chapter is to guide clinicians using the best available evidence as to the optimal timing for surgery and to evaluate the evidence regarding a potential threshold beyond which further delay to surgery adversely affects outcome.

EVIDENCE

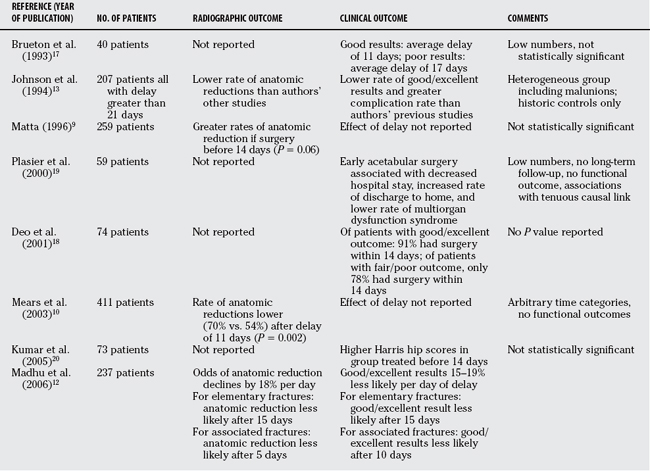

Delay to surgery is mentioned as a contributing factor influencing outcome in several studies summarized in Table 56-1.9,10,12,13,17–20 These studies are retrospective in design and usually originate from a single center. Most of these studies are small and do not achieve statistical significance.9,13,17–20 However, they consistently note a trend of delay to surgery being associated with less favorable radiographic or functional outcome.

A retrospective review from Mears and researchers10 catalogues their experience treating 411patients with acetabular fractures (Level III). This study used Harris hip scores for functional outcomes and radiographs to measure postsurgical reduction. The authors identified several factors associated with poor outcome including articular impaction/abrasion, concomitant femoral neck fracture, elderly age, obesity, osteoporosis, and extensile exposure. The most important variable they identified was the quality of reduction. Time to surgery was categorized by the authors as before 3 days, 3 to 10 days, and 11 or more days. They found the rate of anatomic reduction to be decreased from 70% in those operated on within 10 days to 54% in the group receiving surgery after a delay of 11 days or more (P = 0.002). Matta,9 using similar methods, retrospectively reported his experience with 259 patients with acetabular fracture (Level III). Results were similar, identifying quality of reduction as a major indicator of outcome. In Matta’s9 study, delay to surgery was associated with a trend to poorer reduction after a delay of greater than 14 days (P = 0.06). Time categories in both studies are arbitrary. Neither study specifically examined the effect of delay on clinical outcome, and instead used rate of anatomic reduction as a proxy indicator.

Johnson and coworkers13 conducted a multicenter review of acetabular fractures treated between 21 and 120 days after injury. These represented extreme delays, with many fractures actually being intra-articular malunions. This article compared their results with historic controls only (Level IV). Their reported rate of 57% anatomic reductions and 65% good and excellent clinical results is lower than reported in other studies but impressive considering the nature of these injuries. This article, however, also notes a need for extensile exposures in 33.2% of the patients and significantly greater complication rates including infection (4%), heterotopic ossification (11%), sciatic nerve palsy (10.6%), osteonecrosis (13.8%), and osteoarthritis (24%).

An article from Madhu and coauthors12 specifically analyzed the effect of delay on outcomes of acetabular fractures (Level IV). This is a retrospective study of 254 patients from a teaching center in the United Kingdom. The authors analyzed the effect of delay to surgery on radiologic and clinical outcomes in elementary and associated fracture types. Radiologic outcomes were based on radiographs, with an anatomic reduction defined as no articular step and a gap of 2 mm or less. Functional results were compiled based on Merle d’Aubigne and Postel’s21 system. Rates of anatomic reductions and good/excellent functional outcomes decreased significantly with increased surgical delay. When analyzed as a continuous variable, the odds of obtaining an anatomic reduction or a good/excellent functional outcome declined by between 15% and 19% per day of delay (P < 0.01). As a categoric variable, the authors demonstrate a significant decrease in both functional and radiographic results for elementary fractures after 15 days of delay. For associated fractures, radiologic results declined after 5 days, whereas functional results decreased after 10 days. Complication rates showed a trend to increase with surgical delay, but this did not reach statistical significance in this study.

AREAS OF CONTROVERSY AND UNCERTAINTY

The literature involving acetabular fractures generally consists of retrospective reviews of variable size usually from single institutions. Mears and researchers’9 and Matta’s10 large reviews support accuracy of reduction as an important predictor of outcome. They suggest delay to surgery decreases anatomic reduction rates; however, they do not associate delay directly with functional outcome. Madhu and coauthors’12 review specifically analyzes delay to surgery and has several strengths including large numbers, high rates of follow-up, and convincing statistics. However, each of these studies suffers from similar limitations of retrospective design with a lack of blind assessment of radiographs and functional outcomes. The functional outcome measures used by each study include Harris hip scores and Merle d’Aubigne–Postel scores. These are older, nonvalidated scoring systems.

Many trauma systems suffer from scarcity of surgical and other patient care resources. This is identified by some authors as a source of delay.16 It would be helpful for resource management and triage to identify a threshold where delay begins to threaten chances of obtaining good clinical results. This threshold cannot definitively be stated based on the current literature. However, Madhu and coauthors’12 study shows a decrease of between 15% and 19% in the odds of a good radiographic or clinical result for every day of delay. For elementary fractures, clinical scores significantly decreased after 15 days, whereas associated types decreased after 10 days.

Table 56-2 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of acetabular fractures.

| RECOMMENDATIONS | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

1 Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the Acetabulum, 2nd ed. New York: Springer Verlag, 1993.

2 Tile M, Helfet DL, Kellam JF. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

3 Giannoudis PV, Grotz MR, Papakostidis C, Dinopoulos H. Operative treatment of fractures of the acetabulum: A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87-B:2-9.

4 Judet R, Judet J, Letournel E. Fractures of the acetabulum: Classification and surgical approaches for open reduction-a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46A:1615-1646.

5 Letournel E. Acetabulum fractures: Classification and management. Clin Orthop. 1980;151:81-106.

6 Chiu FY, Chen CM, Lo WH. Surgical treatment of displaced acetabular fractures. 72 cases followed for 10(6-14) years. Injury. 2000;31:181-185.

7 Cole JD, Bolhoffner BR. Acetabular fracture fixation via a modified Stoppa limited intra-pelvic approach: Description of operative technique and preliminary treatment results. Clin Orthop. 1994;305:112-123.

8 Moed BR, Wilson Carr SE, Watson JT. Results of treatment of posterior wall fractures of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:752-758.

9 Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: Accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed within 3 weeks after the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1632-1645.

10 Mears DC, Velyvis JH, Chang CP. Displaced acetabular fractures managed operatively: Indicators of outcome. Clin Orthop. 2003;407:173-186.

11 Kreder HJ, Rozen N, Borkhoff CM, et al. Determinants of functional outcome after simple and complex acetabular fractures involving the posterior wall. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:776-782.

12 Madhu R, Kotnis R, Al-Mousawi A, et al. Outcome of surgery for reconstruction of the acetabulum: The time dependant effect of delay. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1197-1203.

13 Johnson EE, Matta JM, Mast JW, Letournel E. Delayed reconstruction of acetabular fractures 21-120 days following injury. Clin Orthop. 2004;305:20-33.

14 Routt MLJr, Swiontkowski MF. Operative treatment of complex acetabular: Combined anterior and posterior exposures during the same procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72-A:897-904.

15 Griffin DB, Beaule PE, Matta JM. Safety and efficacy of the extended iliofemoral approach in the treatment of complex fractures of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1391-1396.

16 Bircher M, Giannoudis PV. Pelvic trauma management within the UK: Reflection on a failing trauma service. Injury. 2004;35:2-6.

17 Brueton RN. A review of 40 acetabular fractures: The importance of early surgery. Injury. 1993;24:171-174.

18 Deo SD, Tavares SP, Pandey RK, et al. Operative management of acetabular fractures in Oxford. Injury. 2001;32:581-586.

19 Plasier BR, Meldon SW, Super DM, Malangoni MA. Improved outcome after early fixation of acetabular fractures. Injury. 2000;31:81-84.

20 Kumar A, Shah NA, Kershaw SA, Clayson AD. Operative management of acetabular fractures: A review of 73 fractures. Injury. 2005;36:605-612.

21 Merle d’Aubigne R, Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36-A:451-475.