Accidents, poisoning and child protection

Accidents

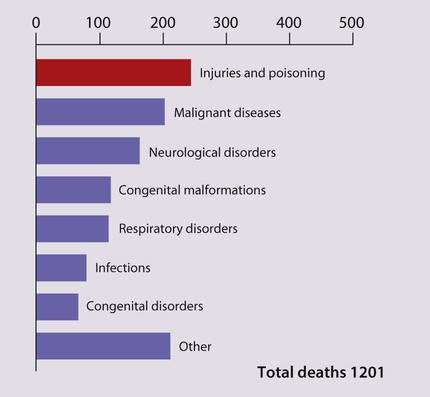

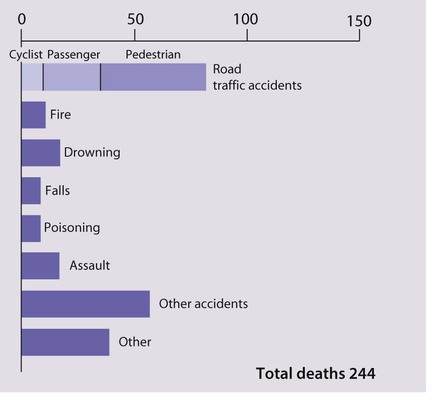

Accidents (now often called ‘unintentional injuries’) are extremely common. In the UK, one in four children attend an A&E department each year; about half because of an accident. They are more common in boys. Most accidents cause only minor injury but can also be fatal. Injuries, mostly accidents, and poisoning are the major cause of death in children 1–14 years of age in the UK (Figs 7.1, 7.2). Accidents also cause significant disability and suffering, including post-traumatic stress disorder. Head injury with brain damage is the major cause of disability from accidents. Cosmetic damage following burns, scalds and other accidents may cause the child profound psychological harm.

Accident prevention

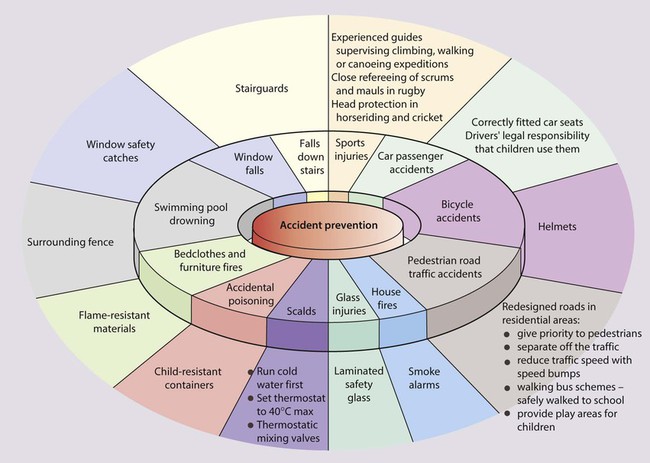

The prevention of childhood accidents is clearly important. Doctors and nurses who treat children and see the effects of accidents are particularly well placed to provide the community with advice on appropriate preventive measures (Fig. 7.3). In order to prevent accidents:

Head injuries

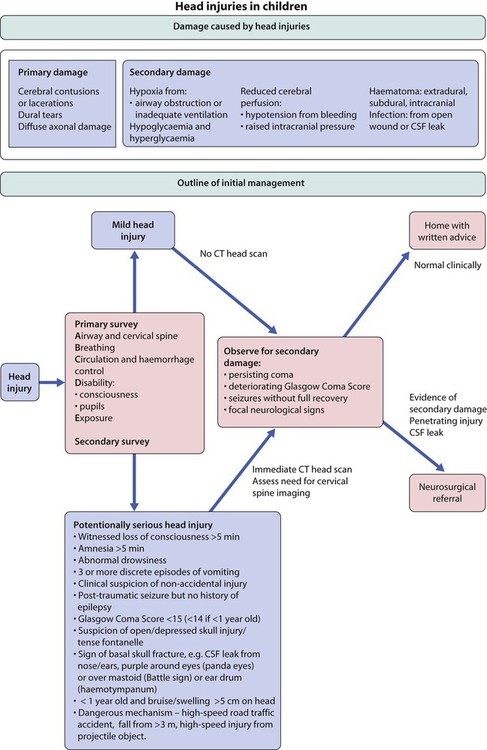

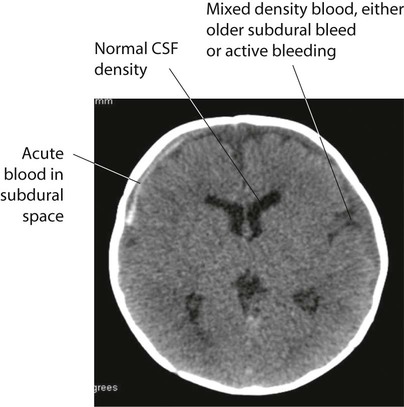

Minor head injuries in childhood are common, and the vast majority of children recover without suffering any ill effects. However, about 1 in 800 of these children develop serious problems. The aim of the management of head injuries is to identify those children requiring treatment and to avoid secondary damage to the brain from hypoxia or poor cerebral perfusion (Fig. 7.4).

Head injury may result in concussion, a reversible impairment of consciousness, a subdural or extradural haematoma or intracerebral contusion (see Ch. 27).

Internal injuries

Children may suffer internal injuries associated with severe trauma. These include:

• Abdominal injuries, including a ruptured spleen, ruptured liver, kidney and bowel. There should be a high index of suspicion for these internal injuries if there has been abdominal trauma or if the clinical setting suggests significant inflicted, i.e. abusive, injury. The child needs close observation. Abdominal ultrasound (focused abdominal sonography in trauma – FAST scan) and X-rays, including CT scan, may be helpful. If there is any doubt, a laparotomy/laparoscopy is undertaken. Intra-abdominal injuries such as a contained splenic bleed are increasingly managed conservatively with close monitoring, but paediatric surgical support must be available immediately in case surgery is required.

• Chest injuries, including pneumothorax and haemopericardium, may require emergency treatment. These children should be managed in a paediatric intensive care unit.

Burns and scalds

Management

The severity of the injury is assessed:

• Is the airway, breathing and circulation satisfactory?

• Was there any smoke inhalation? If this has occurred, there is a danger of subsequent respiratory complications and carbon monoxide poisoning. All affected children should be observed and managed in hospital, with a low threshold to protect the airway before secondary problems develop.

• Depth of the burn. In superficial burns, the skin will be epithelialised from surviving cells. In partial thickness burns, there is some damage to the dermis with blistering, and the skin is pink or mottled; regeneration for superficial and partial thickness burns is from the margins of the wound and from the residual epithelial layer surrounding the hair follicles deep within the dermis. In deep (full thickness) burns, the skin is destroyed down to and including the dermis and looks white or charred, is painless and involves hair follicles, hence skin grafting is often required. Deep burns need assessment and treatment in hospital.

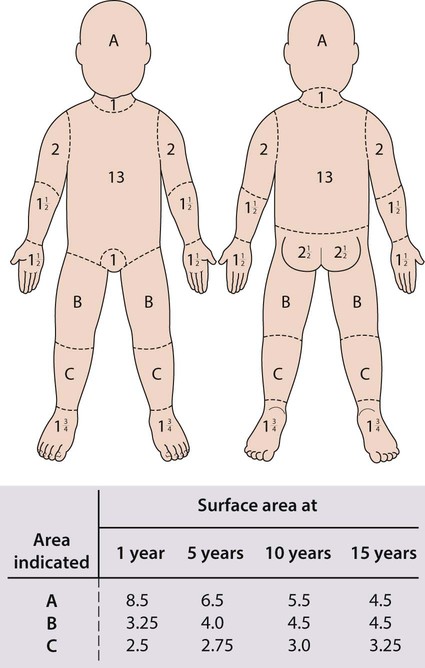

• Surface area of the burn. This should be calculated from a surface area chart (Fig. 7.5). The palm and adducted fingers cover about 1% of the body surface. Burns covering more than 5% full thickness and 10% partial thickness need assessment by burns specialists. Involvement of more than 70% of the body surface carries a poor chance of survival.

• Involvement of special sites. Burns to the face may be disfiguring, those to the mouth may compromise the airway from oedema, and those to the hand/joints may cause functional loss from scarring. Burns to the perineum and other special sites should all be referred to a burns unit.

Treatment

• relieving pain, assessed with a pain score; may require the use of strong analgesics such as intravenous morphine

• treating shock with intravenous fluids, preferably plasma expanders, and close monitoring of haematocrit and urinary output. Children with more than 10% burns will require intravenous fluids

• providing wound care. Burns should be covered with cling film (plastic wrapping), which reduces pain from contact with cold air and reduces the risk of infection. Blisters should be left alone. Irrigation with cold water should only be used briefly to superficial or partial thickness burns covering less than 10% of the body as it may rapidly cause excessive cooling. Tetanus immunisation status must be ascertained and a booster given if required. Ongoing care involves removal of dead tissue and placement of sterile dressings.

Dog bites

Wound management is as important as antimicrobials in preventing infection:

• Copious wound irrigation, toilet and debridement

• Delayed wound closure, especially on limbs, due to increased incidence of infection

• Prophylactic antibiotics if wounds or child is at increased infection risk, i.e. puncture wounds, bites to hands/wrists, crush wounds with devitalised tissue, bites to genitals, child has diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression and in all bites after primary closure.

The antibiotic of choice is co-amoxiclav, as this also covers Pasteurella infection.

Poisoning

• accidental – the vast majority

• deliberate self-poisoning in older children

Accidental poisoning

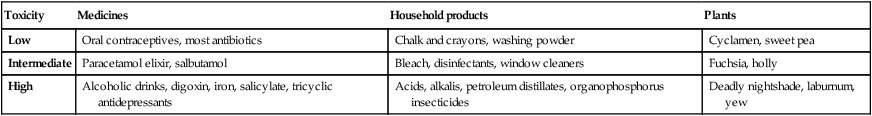

Although many thousands of young children are rushed to doctors’ surgeries or hospital for urgent medical attention following accidental ingestion, most do not develop serious symptoms, as they ingest only a small quantity of poison or take relatively non-toxic substances (Table 7.1). However, a small percentage of children become seriously ill and a very few children die from poisoning each year.

Table 7.1

Potential toxicity in accidental poisoning in infants and young children, with some examples

| Toxicity | Medicines | Household products | Plants |

| Low | Oral contraceptives, most antibiotics | Chalk and crayons, washing powder | Cyclamen, sweet pea |

| Intermediate | Paracetamol elixir, salbutamol | Bleach, disinfectants, window cleaners | Fuchsia, holly |

| High | Alcoholic drinks, digoxin, iron, salicylate, tricyclic antidepressants | Acids, alkalis, petroleum distillates, organophosphorus insecticides | Deadly nightshade, laburnum, yew |

• The introduction of child-resistant containers – in the UK they must be used for paracetamol and salicylate preparations, and certain household products, such as white spirit; an alternative container for tablets is opaque blister packs

• The reduction in the number of tablets per pack

• A reduction in prescriptions of potentially harmful medicines, e.g. aspirin and iron.

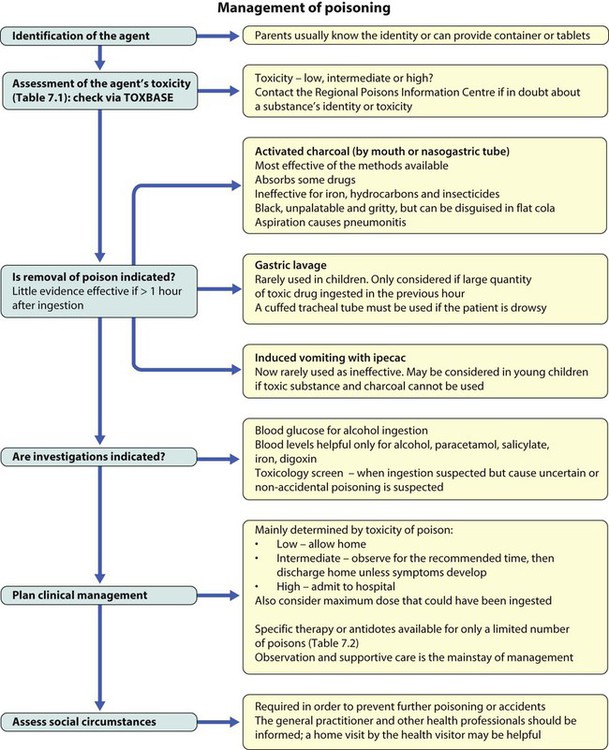

Management

Clinical features that may alert one to poisoning are shown in Table 7.2; however, in young children parents usually know the identity of tablets or other poisons taken (Table 7.3). Management is outlined in Figure 7.8.

Table 7.2

| Tachypnoea | Aspirin, carbon monoxide |

| Slow respiratory rate | Opiates, alcohol |

| Hypertension | Amphetamines, cocaine |

| Hypotension | Tricyclics, opiates, β-blockers, iron (secondary to shock) |

| Convulsions | Tricyclics, organophosphates |

| Tachycardia | Cocaine, antidepressants, amphetamines |

| Bradycardia | β-blockers |

| Large pupils | Tricyclics, cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines |

| Small pupils | Opiates, organophosphates |

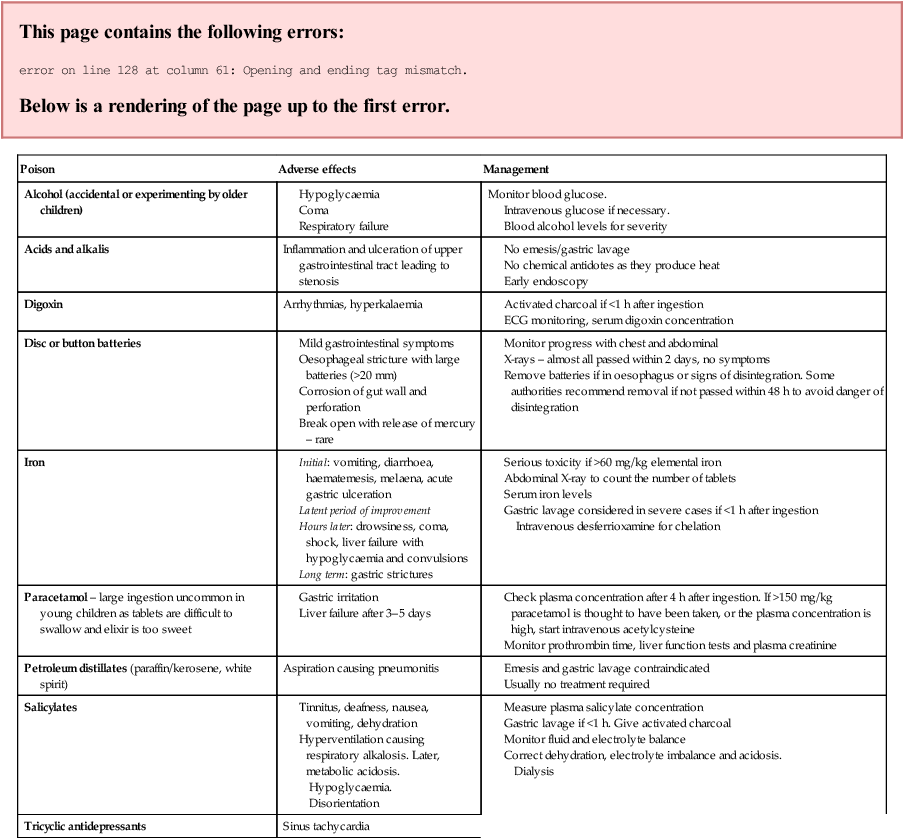

Table 7.3

| Poison | Adverse effects | Management |

| Alcohol (accidental or experimenting by older children) |

Intravenous glucose if necessary.

Blood alcohol levels for severity

Sinus tachycardia

Activated charcoal if within 1 h

Child protection

Following the Second World War, in parallel with the recognition of child abuse, came increasing recognition of human rights. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (see Ch. 1) specifically refers to the child’s right to be protected from mistreatment, both physical and mental. It gives governments the responsibility to ensure that children are properly cared for and protected from violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect.

In the UK, a series of high profile cases of child abuse, most recently Victoria Climbie and Baby P (Box 7.1), have highlighted the difficulties faced by all professionals involved with the welfare of children, whether social workers, teachers, police, healthcare professionals or others, in recognising and responding appropriately to the alerting signs of child abuse.

Types of child abuse and neglect

Neglect

• shelter, including exclusion from home or abandonment

• protection from physical and emotional harm or danger

• adequate supervision, including the use of inadequate caregivers

• access to appropriate medical care or treatment. It may also include neglect or unresponsiveness to a child’s basic emotional needs.

Fabricated or induced illness (FII)

Induction of illness may involve:

• suffocation of the child, which may present as an acute life-threatening event (ALTE)

• administration of noxious substances or poisons

• excessive or unnecessary administration of ordinary substances (e.g. excess salt)

• excess or unnecessary use of medication (prescribed for the child or others)

• the use of medically provided portals of entry (such as gastrostomy buttons, central lines).

Risk factors

Child maltreatment occurs across socioeconomic, religious, cultural, racial and ethnic groups. While no specific causes have been definitively identified that lead a parent or other caregiver to abuse or neglect a child, research has recognised a number of risk factors commonly associated with maltreatment (Box 7.2). Children within families and environments in which these factors exist have a higher probability of experiencing maltreatment. It must be emphasised, however, that while certain factors are often present among families where maltreatment occurs, this does not mean that the presence of these factors will always result in child abuse and neglect. For example, there is a relationship between poverty and maltreatment, yet most people living in poverty do not harm their children.

Presentation

Child abuse and neglect

Child abuse may present with one or more of:

• Psychological symptoms and signs

• A concerning interaction observed between the child and the parent or carer

Factors to consider in the presentation of a physical injury are:

• The child’s age and stage of development

• The history given by the child (if they can communicate)

• The plausibility and/or reasonableness of the explanation for the injury

• Any background, e.g. previous child protection concerns, multiple attendances to A&E or general practitioner

• Delay in reporting the injury

• Inconsistent histories from caregivers

• Inappropriate reaction of parents or caregivers who are vague, evasive, unconcerned or excessively distressed or aggressive.

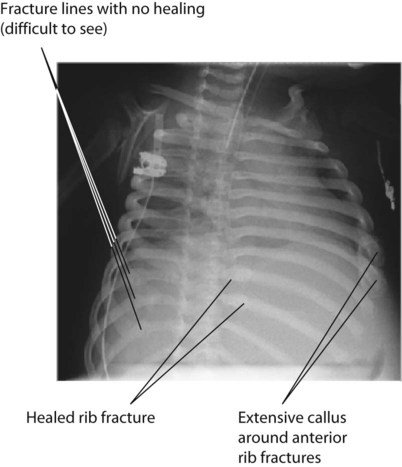

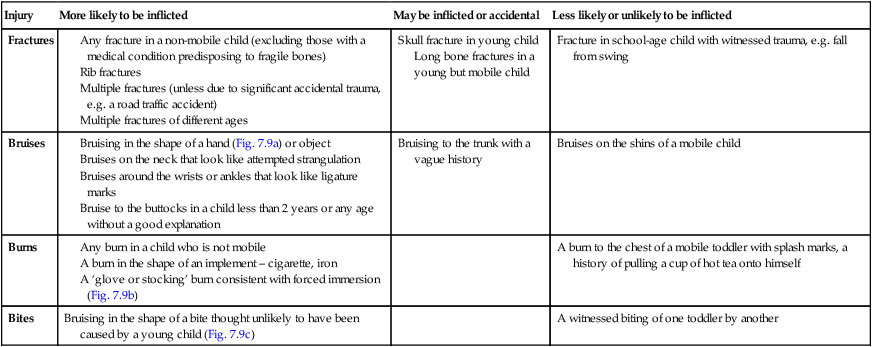

It is often not clear whether an injury is inflicted or non-inflicted. Table 7.4 gives examples of injuries and a guide as to the likelihood that it is due to an inflicted injury. The context and observations of the family are very important in evaluating injuries which may be inflicted.

Table 7.4

Examples of injuries and a guide as to how likely it is due to an inflicted injury

| Injury | More likely to be inflicted | May be inflicted or accidental | Less likely or unlikely to be inflicted |

| Fractures |

Long bone fractures in a young but mobile child

Neglect

Consider the possibility of neglect when the child:

• consistently misses important medical appointments

• lacks needed medical or dental care, immunisations or glasses

• is wearing inadequate clothing in cold weather

Consider the possibility of neglect when the parent or other adult caregiver:

Emotional abuse

There may be clues from the behaviour of the child. This depends on the child’s age:

Sexual abuse

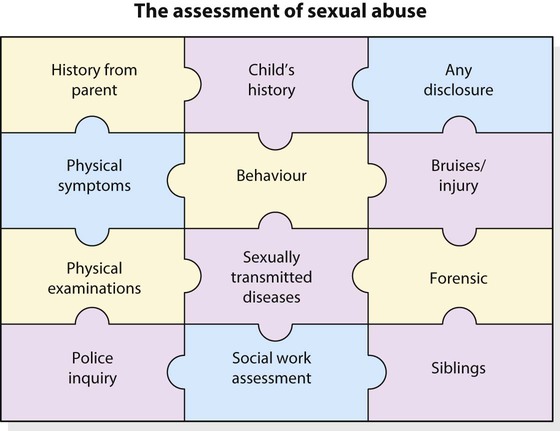

In suspected sexual abuse, information from different sources needs to be pieced together (Fig. 7.14).

Recognition

The child or young person may:

• tell someone about the abuse

• be identified in pornographic material

• be pregnant (by legal definition this is due to sexual abuse for a girl under the age of 13 years)

• have a sexually transmitted infection with no clear explanation (but some sexually transmitted infections can be passed from the mother to the baby during pregnancy or birth).

Signs

Examination of children suspected of having been sexually abused requires a doctor with specific expertise and training, facilities for photographic documentation, sexually transmitted infection screening and management and, where indicated, forensic testing (Fig. 7.14). Forensic testing of swabs from the child or his/her clothing/bedding may reveal DNA from the sperm of the perpetrator.

Investigation

• Bruising – coagulation disorders (Fig. 7.15), Mongolian blue spots on the back or thighs

• Fractures – osteogenesis imperfecta, commonly referred to as brittle bone disease. The type commonly involved with unexplained fractures is type I, which is an autosomal dominant disorder, so there may be a family history. Blue sclerae are a key clinical finding and there may be generalised osteoporosis and wormian bones in the skull (extra bones within skull sutures) on skeletal survey.

• Scalds and cigarette burns – may be misinterpreted in children with bullous impetigo or scalded skin syndrome.