CHAPTER 67 Acalculous Biliary Pain, Acalculous Cholecystitis, Cholesterolosis, Adenomyomatosis, and Polyps of the Gallbladder

This chapter is dedicated to the memory of Lyman E. Bilhartz, MD.

Although gallstones and their complications account for most cholecystectomies,1 a consistent 15% of these operations are performed in patients without gallstones.2 In these patients, the majority of cholecystectomies are performed as treatment for one of two distinct clinical syndromes: acalculous biliary pain and acalculous cholecystitis. As shown in Table 67-1, acalculous biliary pain is generally a disorder of young, predominantly female, ambulatory patients and mimics calculous biliary pain. Acute acalculous cholecystitis is typically a disease of immobilized and critically ill older men with coexisting vascular disease. Because the clinical features and prognosis of these two entities are quite different, they are considered separately in this chapter. Three typically asymptomatic conditions of the gallbladder—cholesterolosis, adenomyomatosis, and gallbladder polyps—are also reviewed.

Table 67-1 Comparison of Acalculous Biliary Pain and Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis

| ACALCULOUS BILIARY PAIN | ACUTE ACALCULOUS CHOLECYSTITIS | |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Female preponderance (80%) | Male preponderance (80%) |

| Young to middle-aged ambulatory patient | Critically ill elderly patient in intensive care unit | |

| Risk factors are similar to those for cholelithiasis (i.e., obesity and multiparity) | Risk factors are preexisting atherosclerosis, recent surgery, and hemodynamic instability | |

| Clinical features | Episodic right upper quadrant or epigastric pain identical to calculous biliary pain | Unexplained sepsis with few localizing signs; rapid progression to gangrene and perforation |

| Physical findings are usually normal | Physical examination may show fever; right upper quadrant tenderness is present in only 25% | |

| Laboratory findings are usually normal | ||

| Leukocytosis and hyperamylasemia may be present | ||

| Diagnostic tests | Ultrasonography shows no stones and usually a normal gallbladder | See Table 67-2 |

| Biliary drainage (Meltzer-Lyon test) typically demonstrates cholesterol crystals | ||

| Stimulated cholescintigraphy using cholecystokinin to measure the gallbladder ejection fraction may identify patients who are likely to improve after cholecystectomy | ||

| Treatment | Elective cholecystectomy for patients with classic biliary pain and either biliary cholesterol crystals or a gallbladder ejection fraction <35% | Urgent cholecystostomy or emergency cholecystectomy for gangrene or perforation |

| Prognosis | Good; attacks continue unless cholecystectomy is performed | Poor, with a mortality rate of 10%-50% |

ACALCULOUS BILIARY PAIN

DEFINITION AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Intense epigastric or right upper quadrant pain that starts suddenly, rises in intensity over a 15-minute period, and continues at a steady plateau for 30 minutes or more before slowly subsiding is characteristic of biliary pain. The localization of pain to the right hypochondrium or radiation to the right shoulder is the most specific finding for a biliary tract origin.3 The attacks of pain are frequently precipitated by ingestion of a meal and may be accompanied by restlessness, nausea, or vomiting. Between attacks, the physical findings are usually normal, with the possible exception of residual upper abdominal tenderness.

When a patient presents with such a history and ultrasonography confirms the presence of gallstones, the management is straightforward—namely, elective cholecystectomy (or perhaps an attempt at medical dissolution of the stones) (see Chapters 65 and 66). In comparison, the management of acalculous biliary pain represents a significant challenge. Patients with acalculous biliary pain have clinical features and biliary-type pain similar to those of patients with cholelithiasis, but a normal gallbladder on ultrasonography and normal serum levels of liver and pancreatic enzymes.4,5 Acalculous biliary pain may stem from a spectrum of overlapping disorders, including chronic acalculous cholecystitis, acalculous biliary disease, gallbladder dysmotility, and biliary dyskinesia, which share symptomatology but differ in the pathologic findings of the resected gallbladder. In patients with acalculous biliary pain, symptomatic improvement following cholecystectomy is more variable.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Ultrasound-negative biliary pain is common in population studies, with reported prevalences of approximately 7% in men and 20% among women.6 Acalculous biliary pain is predominantly a disorder of young women. In one series of more than 100 patients, 83% were female, and the mean age was approximately 30 years.5

The cause of the acalculous biliary pain syndrome is not known, but indirect evidence suggests that several different etiologies may culminate in the same clinical presentation. Stimulated duodenal bile from patients with acalculous biliary pain is more dilute with respect to both bile acids and phospholipids than bile from patients with gallstones or from control women without biliary symptoms.7 The low bile acid concentration may be related to the sluggish or incomplete gallbladder contraction that has been observed in patients with acalculous biliary pain. The lower molar percentage of phospholipids is consistent with the hypothesis that biliary phospholipids are hydrolyzed to free fatty acids, which incite inflammation.

The striking preponderance of young, fertile women among patients with acalculous biliary pain closely parallels the epidemiology of cholelithiasis, suggesting that the two conditions have similar risk factors. Some studies have shown that up to half of patients with acalculous biliary pain actually have microscopic cholelithiasis in resected gallbladder specimens,8 indicating that the original ultrasonogram was falsely negative. Examination of a bile specimen for microlithiasis (Meltzer-Lyon test, discussed later) can be helpful in identifying these patients.

Several studies have shown that a subset of patients with acalculous biliary pain have histologic evidence of cholesterolosis in their resected gallbladders (see later).9–11 Although usually an incidental pathologic finding, cholesterolosis of the gallbladder may, in some patients, disrupt normal gallbladder contraction and result in biliary pain. In other patients, the resected gallbladder demonstrates significant inflammation, characteristic of chronic acalculous cholecystitis.12

Finally, acalculous biliary pain is listed as a functional gastrointestinal disorder by a multinational working committee of gastrointestinal investigators (Rome III classification [see Chapter 118]), with the implication that a pathologic lesion is not required for the diagnosis.4 In patients with a histologically normal gallbladder, a lack of coordination between gallbladder contraction and sphincter of Oddi relaxation, or gallbladder dyskinesia, may cause biliary pain (see Chapter 63). Alternatively, the strong link between acalculous biliary pain and other functional bowel disorders suggests that visceral hypersensitivity may also contribute to biliary pain in patients with a normal gallbladder.6

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

As described earlier, the symptoms of acalculous biliary pain may be indistinguishable from those of cholelithiasis. A careful review of the patient’s complaints should confirm that the symptoms are genuinely suggestive of biliary pain rather than dyspepsia, heartburn, cramping abdominal pain, or flatulence.3 If the symptoms are consistent with biliary pain, a detailed review of the ultrasonogram with a radiologist is warranted. Although gallstones larger than 2 mm are unlikely to be missed (the sensitivity of ultrasound for detecting stones exceeds 95%), other ultrasonographic evidence of gallbladder disease may be overlooked if the primary focus is to exclude stones. Patients with adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder or small cholesterol polyps may have biliary pain that is relieved by cholecystectomy (see later). Determining in whom and when to pursue cholecystectomy for patients with biliary pain and a normal ultrasound result presents a challenge.

Examination of the Bile for Cholesterol Crystals (Meltzer-Lyon Test)

If the ultrasonogram is normal, the bile may be examined for evidence of cholesterol crystals. Long before the advent of ultrasonography, biliary drainage was used to identify patients who were likely to have gallstones. The test has been modified so that the bile is now aspirated during an upper endoscopy after stimulation of gallbladder contraction with intravenous cholecystokinin (CCK).13 The bile should be kept at room temperature and examined immediately (after completion of the endoscopy) under a microscope for the presence of characteristic birefringent, notched rhomboid cholesterol crystals or calcium bilirubinate granules.

Limited clinical studies in patients with acalculous biliary pain have shown that approximately one third have crystals in their bile.9,10 At the time of surgery, most of these patients have documented microlithiasis and pathologically confirmed cholecystitis, and their symptoms resolve following cholecystectomy. The remaining two thirds of patients who do not have crystals in their bile generally have a benign course and rarely return with evidence of significant biliary tract disease.

Stimulated Cholescintigraphy

A second approach to determining which patients with acalculous biliary pain are likely to benefit from cholecystectomy involves calculation of a gallbladder ejection fraction (GBEF) using cholescintigraphy (see Chapter 63). An intravenously administered radiolabeled hepatobiliary agent (e.g., 99mTc-diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid) is concentrated in the gallbladder, and a computer-assisted gamma camera measures activity before and after stimulation of gallbladder contraction with a slow intravenous infusion of CCK over 30 minutes. The GBEF is defined as the change in activity divided by the baseline activity. Studies in healthy volunteers have shown that normal GBEF averages 75% and virtually always exceeds 35%.5 Fatty meal cholescintigraphy is a less costly alternative to the CCK-stimulated test and uses oral fat intake (typically half-and-half milk) to stimulate gallbladder contraction physiologically; normal values for GBEF tend to be lower than those for CCK-stimulated cholescintigraphy.14

Ironically, as stimulated cholescintigraphy gains clinical acceptance, its positive predictive value is expected to fall. When the test was first developed, most patients referred for testing had been experiencing biliary pain for years, thereby allowing ample time for other causes of pain to become evident; therefore, the pretest probability of having a primary gallbladder motility derangement was high, and the specificity of the test was excellent. Now, the test is employed earlier in the evaluation of patients with biliary pain (sometimes immediately after ultrasonography fails to demonstrate gallstones), and patients with nonbiliary or self-limiting diseases have not been weeded out. The earlier that cholescintigraphy is employed, the lower the pretest probability of acalculous biliary pain and, unfortunately, the lower the predictive value of a positive result.15

Fewer than half of patients with acalculous biliary pain have a depressed GBEF, but most of those who do have a depressed GBEF continue to have symptoms when followed for as long as 3 years. If cholecystectomy is performed in these patients, histologic evidence of chronic cholecystitis is found in approximately 90%, cystic duct narrowing in 80%, and cholesterolosis in 30%.11 Long-term symptom relief following cholecystectomy typically occurs in 65% to 80% of patients with an abnormal GBEF5,16,17; however, up to 50% of patients managed without surgery also experience symptom relief.18

ACUTE ACALCULOUS CHOLECYSTITIS

DEFINITION

Acute acalculous cholecystitis is acute inflammation of the gallbladder in the absence of stones. Acute cholecystitis resulting from calculi is discussed in Chapter 65. The designation acalculous cholecystitis has been questioned as incorrectly suggesting that the disease is simply cholecystitis without stones. Instead, the term necrotizing cholecystitis has been proposed to reflect the distinct etiology, pathology, and prognosis of the disease.19

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Acute acalculous cholecystitis accounts for 5% to 10% of cholecystectomies performed in the United States. In fact, of the cholecystectomies performed in postoperative or hospitalized patients recovering from trauma or burns, more than half are for acalculous disease.20

Less commonly, acute acalculous cholecystitis may occur in the absence of antecedent trauma or stress, especially in children,21 elderly patients with coexisting vascular disease,22 bone marrow transplant recipients, patients who receive cytotoxic drugs via the hepatic artery,23 and patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.24 In some cases, specific infectious causes can be identified, such as Salmonella,25 Staphylococcus aureus,26 cytomegalovirus in immunocompromised patients,27 and Epstein-Barr virus in children.21 Systemic vasculitides such as polyarteritis nodosa and systemic lupus erythematosus may manifest as acute acalculous cholecystitis caused by ischemic injury to the gallbladder.28 Finally, acute acalculous cholecystitis is being recognized increasingly in otherwise healthy people without any risk factors.29,30 As a group, patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis are more likely to be men and old than are patients with cholecystitis caused by calculi, cases of which cluster in younger women.31

PATHOGENESIS

Most cases of acute acalculous cholecystitis occur in the setting of prolonged fasting, immobility, and hemodynamic instability. The gallbladder epithelium, although normally a robust tissue, is exposed continuously to one of the most noxious agents in the body: a concentrated solution of bile acid detergents. In the course of a normal day, the gallbladder empties the concentrated bile several times and is replenished with dilute (and presumably less noxious) hepatic bile. With prolonged fasting, the gallbladder is not stimulated by CCK to empty, and concentrated bile stagnates in the gallbladder lumen.32 In addition, the gallbladder epithelium has relatively high metabolic energy requirements in order to absorb electrolytes and water from the bile. Therefore, in an immobile, fasting patient with splanchnic vasoconstriction (often resulting from septic shock in a patient in the intensive care unit), ischemic and chemical injury to the gallbladder epithelium may occur.33 A study that compared the microcirculation of gallbladders removed for gallstone disease or acute acalculous cholecystitis showed that the capillaries barely filled in acalculous cholecystitis, indicating that disturbed microcirculation may play an important role in its pathogenesis.34

Inappropriate activation of factor XII (demonstrated to initiate gallbladder inflammation in animals)35 and local release of prostaglandins in the gallbladder wall36,37 have also been implicated in the tissue injury associated with acalculous cholecystitis. In animal models, tissue destruction can be attenuated by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis with indomethacin. Expression of tight junction proteins in the gallbladder epithelium of patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis differs from calculous cholecystitis, perhaps reflecting the role of increased gallbladder wall permeability in the systemic inflammatory response.38 Infection of the gallbladder mucosa with bacteria, usually gram-negative enteric organisms and anaerobes,39 is thought to be a secondary event in acute acalculous cholecystitis, following rather than causing the initial injury.

One postulated explanation for the rising incidence of acute acalculous cholecystitis, particularly in younger patients, is obesity and the accompanying increase in gallbladder wall fat, which has been demonstrated to interfere with gallbladder emptying in animal models. In one study, sixteen patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis had significantly more gallbladder wall fat than normal subjects without cholecystitis.40

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical features of acute acalculous cholecystitis often differ from those of acute cholecystitis caused by stone disease. Although right upper quadrant pain, fever, localized tenderness overlying the gallbladder, and leukocytosis may be evident in classic presentations, such as those of younger outpatients, some or all of these features are commonly lacking in elderly postoperative patients.41 Symptoms or signs referable to the right upper quadrant are initially absent in 75% of cases. Unexplained fever or hyperamylasemia may be the only clues that something is amiss.

Compared with the clinical course of typical calculous cholecystitis, that of acute acalculous cholecystitis is more fulminant. By the time the diagnosis has been made, at least half of the patients have experienced a complication of cholecystitis, such as gangrene or a confined perforation of the gallbladder.42 Empyema of the gallbladder and ascending cholangitis may further complicate cases in which bacterial superinfection of the gallbladder has occurred. Because the disease often occurs in debilitated patients and complications occur rapidly, the mortality rate of acute acalculous cholecystitis is high, ranging from 10% to 50%, as compared with a 1% mortality rate in patients with calculous cholecystitis. Such high mortality rates have led some investigators to propose that empirical cholecystostomy be considered in gravely ill patients in the intensive care unit in whom no source of sepsis can be found.43

DIAGNOSIS

The rapid development of complications in acute acalculous cholecystitis makes early diagnosis critical for avoiding excessive mortality. Unfortunately, the lack of specific clinical findings pointing to the gallbladder, combined with a confusing clinical picture related to antecedent surgery or trauma, makes early diagnosis difficult. For elderly patients at risk, a high index of suspicion for biliary tract sepsis is the best hope for early recognition and treatment. Table 67-2 delineates several diagnostic criteria for acute acalculous cholecystitis.

Table 67-2 Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis

| TECHNIQUE | FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Clinical examination | Right upper quadrant tenderness is helpful, if present, but is lacking in three quarters of cases |

| Unexplained fever, leukocytosis, or hyperamylasemia is frequently the only finding | |

| Ultrasonography | Thickened gallbladder wall (defined as >4 mm) in the absence of ascites and hypoalbuminemia (defined as serum albumin <3.2 g/dL) |

| Presence of sonographic Murphy’s sign (maximum tenderness over the ultrasonographically localized gallbladder) | |

| Pericholecystic fluid collection | |

| Bedside availability is a major advantage | |

| Computed tomography | Thickened gallbladder wall (defined as >4 mm) in the absence of ascites and hypoalbuminemia |

| Pericholecystic fluid, subserosal edema (in the absence of ascites), intramural gas, or sloughed mucosa | |

| Best test for excluding other intra-abdominal diseases but requires moving the patient to a scanner | |

| Hepatobiliary scintigraphy | Nonvisualization of the gallbladder with normal excretion of radionuclide into the bile duct and duodenum indicates a positive result for acute cholecystitis |

| Results in critically ill, immobilized patients may be falsely positive because of viscous bile | |

| Morphine augmentation may reduce the number of false-positive results (see text) | |

| Better at excluding than confirming acute cholecystitis |

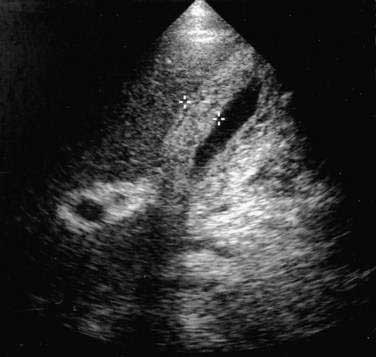

Ultrasonography

In the evaluation of patients with suspected acute acalculous cholecystitis, ultrasonography offers the distinct advantages of being widely available and easily transportable to the bedside.44 Three ultrasonographic findings indicative of gallbladder disease are a (1) thickened gallbladder wall (defined as >4 mm) in the absence of ascites or hypoalbuminemia, (2) sonographic Murphy’s sign (defined as maximum tenderness over the ultrasonographically localized gallbladder), and (3) pericholecystic fluid collection. A thickened gallbladder wall (Fig. 67-1) is not specific for cholecystitis but in the proper clinical setting is suggestive of gallbladder involvement and should prompt further evaluation. A sonographic Murphy’s sign is operator dependent and requires a cooperative patient but, when present, is a reliable indicator of gallbladder inflammation.45 A pericholecystic fluid collection indicates advanced disease. Sensitivity rates of ultrasonography for detecting acute acalculous cholecystitis have been reported to range from 67% to 92%, with specificity rates of more than 90%.44 Investigators have proposed an ultrasonographic scoring system to improve the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in critically ill patients.46 Two points are given for distention of the gallbladder or thickening of the gallbladder wall, and 1 point each is given for “striated” thickening (alternating hypoechoic and hyperechoic layers) of the gallbladder wall, sludge, or pericholecystic fluid. Scores of 6 or higher accurately predict acalculous cholecystitis.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) findings suggestive of cholecystitis include gallbladder wall thickening (>4 mm), pericholecystic fluid, subserosal edema (in the absence of ascites), intramural gas, and sloughed gallbladder mucosa. Sensitivity and specificity rates of these findings for predicting acute acalculous cholecystitis at surgery have been reported to exceed 95%. CT is also superior to ultrasonography in detecting disease elsewhere in the abdomen that could be the cause of a patient’s fever or abdominal pain.47 An obvious disadvantage of CT is that it cannot be performed at the bedside, which is necessary in many critically ill patients. Several investigators have emphasized that CT is complementary to ultrasonography and often detects gallbladder disease in high-risk patients with normal ultrasonographic findings.

Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy may be useful for excluding cystic duct obstruction in patients with clinical features suggestive of acute cholecystitis. Under normal conditions, intravenously administered radionuclide is taken up by the liver, secreted into bile, concentrated in the gallbladder (where it produces a “hot spot” on a scan), and emptied into the duodenum. A positive scan result for cystic duct obstruction is defined as failure of filling of the gallbladder despite the normal passage of radionuclide into the duodenum. In suspected calculous cholecystitis, the pathogenesis of which involves obstruction of the cystic duct by a stone, filling of the gallbladder on scintigraphy virtually excludes cholecystitis as the cause of the patient’s symptoms.48

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy is less precise in acute acalculous cholecystitis. Gallbladder and cystic wall edema can cause an obstructive picture similar to calculous cholecystitis on scintigraphy. Patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis have often fasted for prolonged periods, a state that can result in concentrated, viscous bile that flows poorly through the cystic duct and causes a false-positive hepatobiliary scan result. Most patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis (in contrast to those with calculi) do not have an obstructed cystic duct; hence, hepatobiliary scans can be falsely negative as well.49 The sensitivity of the test may exceed 90%, but the lack of specificity in fasted, critically ill patients limits the usefulness of the test primarily to excluding acute acalculous cholecystitis rather than confirming the diagnosis. A study in which ultrasonography and cholescintigraphy were performed in critically ill patients found cholescintigraphy to be useful for the early diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis, whereas ultrasonography alone did not permit an early decision regarding the need for surgery.50

In an effort to improve the accuracy of biliary scintigraphy, investigators have proposed the use of morphine-augmented cholescintigraphy, in which morphine sulfate is administered intravenously (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) to patients in whom the gallbladder has not been visualized on standard cholescintigraphy.51 The rationale for this procedure is that morphine increases resistance to the flow of bile through the sphincter of Oddi and thus forces filling of the gallbladder if the cystic duct is patent, thereby reducing the likelihood of a false-positive result. In approximately 60% of critically ill patients with possible biliary tract sepsis and a nonvisualized gallbladder on standard cholescintigraphy, the gallbladder is visualized after morphine augmentation, and, therefore, acute cholecystitis can be excluded as the source of sepsis.

TREATMENT

Surgical Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy

Traditionally, the definitive therapeutic approach for acute acalculous cholecystitis has been urgent laparotomy and cholecystectomy (see Chapter 66). Nowadays, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard approach.52 In patients too unstable to tolerate anesthesia, radiographically guided percutaneous cholecystostomy can be performed53; definitive cholecystectomy can be undertaken when the patient is stable, if necessary.

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy

Several investigators have reported favorable results with the ultrasonographically guided percutaneous transhepatic placement of a cholecystostomy drainage tube, coupled with intravenous administration of antibiotics, as definitive therapy in patients in whom surgery poses a high risk.43,54–55 Studies suggest that most patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis can be treated with percutaneous drainage; if the postdrainage cholangiogram is normal, the catheter can be removed, and cholecystectomy is not necessary.54,56

Transpapillary Endoscopic Cholecystostomy

Some critically ill patients with suspected acute acalculous cholecystitis are poor candidates for ultrasonographically guided percutaneous cholecystostomy, let alone surgery, because of massive ascites or uncorrectable coagulopathy. Such patients may benefit from an endoscopic approach in which the cystic duct is selectively cannulated during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with an obliquely angled guidewire that tracks along the lateral wall of the bile duct and facilitates cannulation of the cystic duct.57 If the wire can negotiate the spiral valves within the cystic duct successfully, a nasobiliary catheter is introduced over the guidewire into the gallbladder, the contents are aspirated, and the gallbladder is lavaged with 1% N-acetylcysteine in saline to dissolve mucus and sludge. The nasocholecystostomy catheter is allowed to drain by gravity for several days and can be easily removed when the patient has recovered and is stable.

Studies have shown that successful intubation of the gallbladder can be achieved in 90% of attempts and that drainage and lavage of the viscous black bile and sludge from the gallbladder result in clinical resolution in most of these critically ill patients. The technique is more cumbersome and expensive than ultrasonographic placement of a cholecystostomy tube and should be reserved for patients who would not tolerate a percutaneous approach.58

PREVENTION

Daily stimulation of gallbladder contraction with intravenously administered CCK, 50 ng/kg over 10 minutes, has been shown to prevent the formation of gallbladder sludge in fasting patients receiving total parenteral nutrition (see Chapter 62).59 The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of such prophylaxis remain to be established.

CHOLESTEROLOSIS

DEFINITION

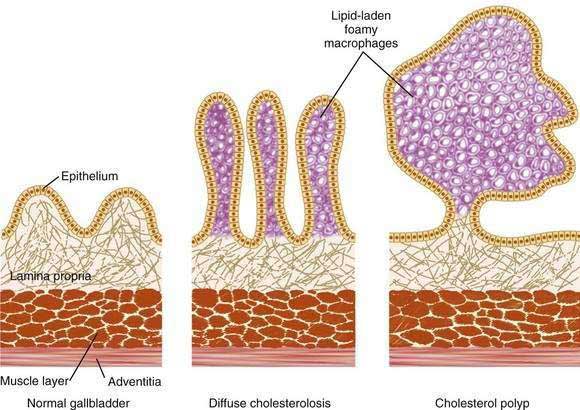

Cholesterolosis is an acquired histologic abnormality of the gallbladder epithelium characterized by excessive accumulation of cholesterol esters and triglyceride within epithelial macrophages (Fig. 67-2).60 Clinicians generally encounter the lesion only as an incidental pathologic finding after surgical resection of the gallbladder, although the diagnosis may be suspected in certain patients before surgery.

Figure 67-2. Schematic representation of a normal gallbladder, diffuse cholesterolosis, and a cholesterol polyp. Note the distribution of lipid-laden foamy macrophages in cholesterolosis and the cholesterol polyp. The diffuse form of cholesterolosis (center; see also Fig. 67-3) accounts for 80% of cases and generally causes no symptoms. Cholesterol polyps (right), present in 20% of cases, are typically small, fragile excrescences that have a tendency to ulcerate or detach spontaneously from the mucosa. Although usually asymptomatic, these polyps have been associated with biliary pain and even acute pancreatitis.

Cholesterolosis, as well as adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder (see later), has been classified as one of the hyperplastic cholecystoses, a term introduced in 1960 to describe several diseases of the gallbladder thought to share the common features of mucosal hyperplasia, hyperconcentration and hyperexcretion of dye on cholecystography, and absence of inflammation.61 The proponents of this concept believed that biliary pain, in the absence of gallstones, could be explained by the presence of one of the hyperplastic cholecystoses. Other investigators, citing the lack of a common etiology and the nonspecificity of the clinical features, have recommended that the term hyperplastic cholecystoses be abandoned.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although cholesterolosis has been recognized as a distinct pathologic entity for more than a century, its actual prevalence remains a matter of some dispute. Depending on whether gross or microscopic criteria are used for diagnosis, the frequency of cholesterolosis in autopsy specimens has ranged from 5% to 40%. A large autopsy series involving more than 1300 cases in which each gallbladder was examined microscopically found the prevalence of cholesterolosis to be 12%.62 When surgically resected gallbladders were examined, the frequency was, not surprisingly, about 50% higher (18%) than that found in autopsy material.63 The incidence of cholesterolosis has not been calculated because its onset is rarely known.

The epidemiology of cholesterolosis is analogous to that of cholesterol gallstone disease,64 in that similar groups of persons are predisposed; however, the two lesions occur independently and do not usually coexist in the same person. Like gallstone disease, cholesterolosis is uncommon in children (the youngest reported patient was a 13-year-old girl) and shows a marked predilection for women up to 60 years of age. After that, the gender differences are less pronounced. No racial, ethnic, or geographic differences in prevalence have been described, although if the analogy with cholesterol gallstone disease is extended, the prevalence would be expected to be higher in Western than non-Western societies. Obesity also appears to be a risk factor for cholesterolosis; a frequency of 38% has been observed in gallbladders resected during weight loss surgery.65

PATHOLOGY

Cholesterolosis is defined pathologically by the accumulation of lipid (cholesteryl esters and triglyceride) within the gallbladder mucosa. The four patterns of lipid deposition are as follows60:

Gross Appearance

When the gallbladder is inspected visually at the time of laparotomy or laparoscopy, a diagnosis of cholesterolosis can be made in 20% of the cases on the basis of the gross appearance of the gallbladder mucosa as seen through the translucent serosal surface. When the gallbladder is opened, the mucosa characteristically has pale, yellow linear streaks running longitudinally, giving rise to the term strawberry gallbladder (although the mucosa is usually bile stained rather than red). When cholesterolosis is diagnosed at the time of surgical resection of the gallbladder, gallstones are also present in 50% of cases. If the diagnosis of cholesterolosis is made at autopsy, stones are present in only 10%,62 demonstrating that the two disease processes are independent of each other.

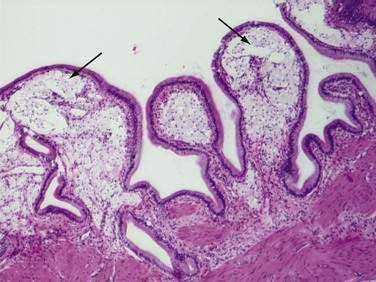

Microscopic Appearance

Hyperplasia of the mucosa is invariably present and is described as marked in 50% of cases. Usually, the hyperplasia is of the villous type. The most prominent feature is an abundance of macrophages within the elongated villi. Each macrophage is stuffed with lipid droplets and has a characteristic appearance of a foam cell (Fig. 67-3). In milder cases, the foam cells are limited to the tips of the villi (accounting for the linear streaks seen on gross examination); with more severe involvement, the foam cells may fill the entire villi and spill over into the underlying submucosa. Although extracellular deposits of lipid are rare, small yellow particles (lipoidic corpuscles) representing detached masses of foam cells are occasionally seen floating in the bile.

PATHOGENESIS

The cause of the accumulation of cholesteryl esters and triglyceride in cholesterolosis remains obscure.66 Postulated mechanisms are that the cholesterol is derived from the blood67 or that mechanical factors that impede emptying of the gallbladder lead to local deposition of lipid.68 Data have shown unequivocally that the gallbladder epithelium is capable of absorbing cholesterol from the bile, as might be expected in epithelium that is embryologically and histologically similar to intestinal absorptive cells.69,70 Moreover, the cholesterol in gallbladder bile is already in the ideal physical state for absorption (i.e., a mixed micelle). The question remains as to why, in some patients, resorbed biliary cholesterol is esterified and then stored in foamy macrophages as cholesterolosis.71 Like cholesterol stones, cholesterolosis is frequently, but not always, found in gallbladders exposed to bile that is supersaturated with cholesterol.72 The two disorders (cholesterolosis and stone disease), both of which lead to the ectopic accumulation of cholesterol, probably share common pathogenic mechanisms (such as the secretion of abnormal bile) but progress independently in a given patient, depending on other factors such as the presence of nucleating proteins in bile and the rate of mucosal esterification of cholesterol.73 Cholesterolosis is not associated with high serum cholesterol levels.64

CLINICAL FEATURES

Cholesterolosis usually does not cause symptoms, as is evident by how frequently autopsy specimens show the lesion in patients who never had biliary symptoms. On occasion, individual patients have dull, vague, right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that resembles biliary pain and are found subsequently to have cholesterolosis without stones or gallbladder inflammation after cholecystectomy. Of the patients who undergo cholecystectomy for the syndrome of acalculous biliary pain, pain is more likely to resolve in those in whom incidental cholesterolosis is found on pathologic examination of the gallbladder than in those in whom cholesterolosis is not found.74

In retrospective surgical series of nearly 4000 gallbladders removed by cholecystectomy, 55 patients with acalculous cholesterolosis were identified.75 The investigators found that nearly half of these patients had presented with recurrent pancreatitis of unknown etiology and speculated that small cholesterol polyps had detached from the gallbladder wall and transiently obstructed the sphincter of Oddi, thereby provoking the acute pancreatitis. In 5 years of postoperative follow-up, pancreatitis did not recur. These investigators and others76,77 have suggested that cholesterolosis (or more specifically, cholesterol polyps) should be considered in the differential diagnosis of idiopathic pancreatitis.

DIAGNOSIS

Diffuse cholesterolosis (which, as noted earlier, constitutes 80% of cases) is only rarely detectable by either ultrasonography or oral cholecystography. In the polypoid form, however, polyps of sufficient size have a characteristic appearance on ultrasonography as single or multiple, nonshadowing, fixed echoes that project into the lumen of the gallbladder.78 Most of the polyps are small (2 to 10 mm). The polyps can be identified accurately as cholesterolosis polyps by endoscopic ultrasonography, which demonstrates a characteristic aggregation of hyperechoic spots.79 On oral cholecystography, the polyps appear as small, round radiolucencies in the lumen of the opacified gallbladder and are best demonstrated after the gallbladder has emptied partially and abdominal compression has been applied.

TREATMENT

Because cholesterolosis is only rarely diagnosed before resection of the gallbladder, the issue of treatment is usually irrelevant. In the rare case of polypoid cholesterolosis diagnosed on ultrasonography or cholecystography, the absence of biliary tract symptoms argues against any intervention. If the patient has symptoms consistent with biliary pain or pancreatitis, a cholecystectomy is indicated.75 There is no medical therapy for cholesterolosis.

ADENOMYOMATOSIS

DEFINITION

Adenomyomatosis (an unwieldy term that obscures its meaning) of the gallbladder is an acquired, hyperplastic lesion characterized by excessive proliferation of surface epithelium with invaginations into the thickened muscularis or even more deeply.80 Despite the prefix adeno-, the lesion is generally benign and unrelated to adenomatous epithelia elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Simple adenomyomatosis is not thought to have the potential for malignant transformation.

The literature on this obscure condition is complicated by the use of a number of different terms to describe the same lesion. One researcher noted that adenomyomatosis has been described by at least 18 distinct names, the more common of which are adenomyoma (used when the lesion is localized to the gallbladder fundus), diverticulosis of the gallbladder (ignores the hyperplasia), cholecystitis glandularis proliferans (overemphasizes the role of inflammation), Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses (familiar but anatomically incorrect), adenomyosis, and adenomyomatous hyperplasia.81 Some terms are used in the radiologic literature, whereas others are used exclusively by pathologists. None is familiar to most gastroenterologists.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder varies greatly according to the criteria used for diagnosis and whether resected gallbladders or autopsy specimens are examined. In a large series of more than 10,000 cholecystectomy specimens, Shepard and associates82 found only 103 cases of adenomyomatosis, for a prevalence of about 1%. The lesion is more common in women than men by a 3 : 1 ratio, and the prevalence rises with age. Neither ethnic nor geographic differences in prevalence have been described.

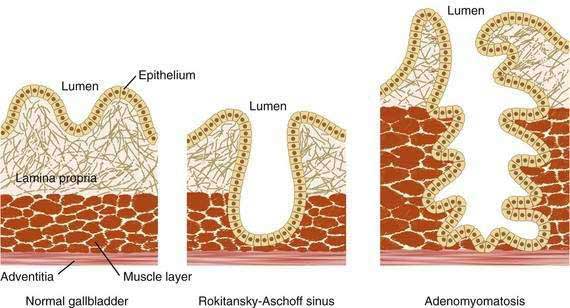

PATHOLOGY

A review of the normal histologic architecture of the gallbladder and Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses is useful for understanding the pathology of adenomyomatosis (Fig. 67-4). Unlike the small intestine, the gallbladder has no muscularis mucosa, and the lamina propria abuts directly on the muscular layer. In childhood, the epithelial layer is cast up into folds and supported by the lamina propria. As the gallbladder ages, the valleys of the epithelial layer may deepen so that they penetrate into the muscular layer and form Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses. These sinuses are acquired lesions present in about 90% of resected gallbladders. If the Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses are deep and branching and are accompanied by thickening (hyperplasia) of the muscular layer, a diagnosis of adenomyomatosis can be made.80 Rupture of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses is thought to underlie the rare entity xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, in which the gallbladder is involved in an inflammatory process with lipid-laden macrophages.

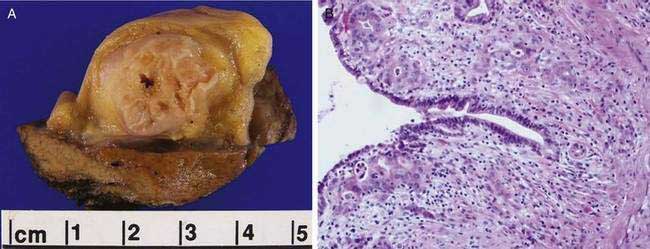

Gross Appearance

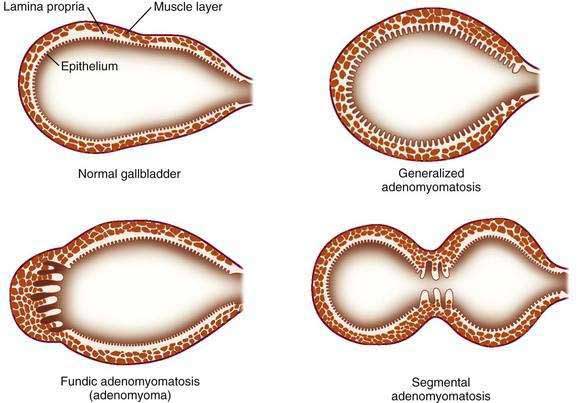

Adenomyomatosis may involve the entire gallbladder (diffuse or generalized adenomyomatosis) or, more commonly, may be localized to the gallbladder fundus, in which case the lesion is often termed adenomyoma. On rare occasions, the process may be limited to an annular segment of the gallbladder wall (segmental adenomyomatosis) and may give rise to luminal narrowing and a “dumbbell-shaped” gallbladder (Fig. 67-5). In any case, the involved portion of the gallbladder wall is thickened to 10 mm or more, and the muscle layer is three to five times its normal thickness. On cut sections, cystic dilatations of the Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses are evident and may be filled with pigmented debris or calculi.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of adenomyomatosis is unknown. Increased intraluminal pressure in the gallbladder from mechanical obstruction (e.g., from an obstructing calculus, kink in the cystic duct, or congenital septum) has been postulated to result in cystic dilatation of the Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses, subsequent hyperplasia of the muscle layer, and adenomyomatosis.80 Like pressure-related colonic diverticula, Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses are most likely to be found where the muscle layer is weakest (at the site of a penetrating blood vessel). Nevertheless, evidence of outflow obstruction of the gallbladder is not always found; for example, calculi are present in only about 60% of cases of adenomyomatosis.82 Some investigators have proposed that adenomyomatosis is a consequence of chronic inflammation, but inflammation is not always present, particularly when the lesion is localized to the fundus.83 Finally, several investigators have noted an association between adenomyomatosis and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union (see Chapter 55). In one study, half of the patients with adenomyomatosis had anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union,84 and in another study, one third of patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union had adenomyomatosis.85 The pathogenic link between these two peculiar entities is unclear.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Adenomyomatosis, like cholesterolosis, usually causes no symptoms and is typically an incidental finding at autopsy or surgical resection. As noted earlier, gallstones are present in more than half of the resected gallbladders that are found to have adenomyomatosis; in these cases the symptoms can be ascribed to the stones.82 Uncommonly, acalculous adenomyomatosis appears to cause symptoms indistinguishable from the biliary pain of cholelithiasis.

On rare occasions, adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder has been found in association with adenomyomatosis (Fig. 67-6)86; however, the malignancy is often far removed from the localized area of adenomyomatosis, and the association has been thought to be coincidental rather than causal. Nevertheless, several reports of adenocarcinoma occurring in an area of gallbladder wall involved with adenomyomatosis have created diagnostic uncertainty on ultrasonography or cholecystography.87 A retrospective review of more than 3000 resected gallbladders revealed a significantly higher frequency (6.4%) of gallbladder cancer in gallbladders with the segmental form of adenomyomatosis than would have been expected by chance alone. The investigators proposed that segmental adenomyomatosis should be considered a potentially premalignant lesion.88 A second review of gallbladder cancers associated with segmental adenomyomatosis revealed a spectrum of cytologic atypia in the specimens ranging from hyperplastic to malignant epithelium, suggestive of neoplastic progression.89

DIAGNOSIS

On oral cholecystography (see Chapter 65), the mural diverticula that constitute Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses may fill with contrast material and produce characteristic radiopaque dots that parallel the margin of the gallbladder lumen.90 Any portion of the gallbladder wall may be involved (Fig. 67-7). Localized, fundal adenomyomatosis (adenomyoma) may manifest as a filling defect in the fundus, whereas segmental adenomyomatosis may appear as a circumferential narrowing of the gallbladder lumen. As is the case with cholesterolosis, the radiologic findings in adenomyomatosis are best appreciated when the gallbladder has partially emptied of contrast material and external pressure has been applied during the examination.90

Although ultrasonography has largely replaced oral cholecystography in the evaluation of the gallbladder, the ultrasonographic findings in adenomyomatosis are less specific. A thickened gallbladder wall (>4 mm) is not specific for adenomyomatosis and can also be seen in many other conditions such as liver disease with ascites.91 Carefully performed studies in which radiologic and ultrasonographic findings of adenomyomatosis were correlated with pathologic findings have shown that diffuse or segmental thickening of the gallbladder wall in association with intramural diverticula (seen as round anechoic foci) accurately predicts adenomyomatosis.92 If the intramural diverticula (dilated Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses) are filled with sludge or small calculi, the lesions may appear echogenic with acoustic shadowing or a reverberation artifact.93 Endoscopic ultrasonography may demonstrate the characteristic finding of multiple microcysts, corresponding to the proliferated Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses.79 CT and magnetic resonance imaging findings in adenomyomatosis include94 differential enhancement of gallbladder wall layers, detection of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses within a thickened gallbladder wall,95 and subserosal fatty proliferation.96 In a study of 20 patients with surgically proved adenomyomatosis who had preoperative ultrasound, helical CT, and MRI evaluation, the diagnostic accuracies of the three modalities were 66%, 75%, and 93%, respectively.97 In one case report, an adenomyoma without histologic evidence of cancer was the cause of a false-positive finding on 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET), likely because of the associated inflammatory activity.98

TREATMENT

In the absence of biliary tract symptoms, adenomyomatosis requires no treatment. If the patient has biliary pain and radiographic or ultrasonographic evidence of adenomyomatosis with calculi, a cholecystectomy is indicated. A more difficult clinical problem arises when a patient is symptomatic and has suspected adenomyomatosis but no stones.87 In such cases, the more extensive or severe the adenomyomatosis appears to be, the more likely that the symptoms are related to the lesion and that the patient will benefit from cholecystectomy. Fear of malignant transformation is not a reason to operate, unless an ultrasonographic or radiologic image suggests a mass or perhaps shows the segmental form of adenomyomatosis.99

POLYPS OF THE GALLBLADDER

DEFINITION

The term polyp of the gallbladder is used to describe any mucosal projection into the lumen of the gallbladder.100 The vast majority of gallbladder polyps are the result of lipid deposits or inflammation, rather than neoplasms. Because the nature of a polyp cannot be defined without histologic evaluation, however, clinicians must decide whether the concern of malignancy is sufficient to perform cholecystectomy based on indirect information such as the radiographic appearance of the polyp, patient demographics, and symptoms.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The frequency of gallbladder polyps, defined either pathologically or radiologically,101 ranges from 1% to 4%. Often, gallbladder polyps are an incidental finding at the time of cholecystectomy.

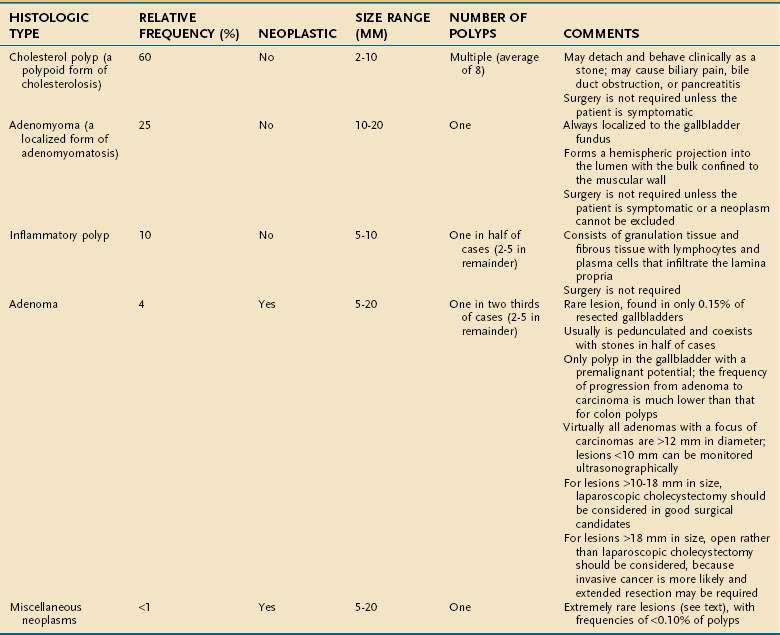

PATHOLOGY

Polyps of the gallbladder may be classified as shown in Table 67-3 as either non-neoplastic (95% of all gallbladder polyps) or neoplastic.102

Cholesterol Polyps

Cholesterol polyps (also known as papillomas of the gallbladder, although the term should be discarded) are the most common type of gallbladder polyp. They are benign variants of cholesterolosis that result from infiltration of the lamina propria with lipid-laden foamy macrophages. The pathogenesis of cholesterol polyps is discussed in the section on cholesterolosis (see earlier). Cholesterol polyps are typically small (>10 mm in diameter), pedunculated polyps that are attached to the mucosa by a thin, fragile stalk.102 Frequently, detached tiny cholesterol polyps are found floating in the bile when the gallbladder is opened in the operating room.103 Although they may be solitary in 20% of cases, the mean number of cholesterol polyps present in one series was eight.104

Adenomyomas

Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder localized to the fundus may produce a hemispheric projection into the lumen that resembles a polyp. Such a lesion has come to be known as an adenomyoma, although it is not neoplastic in origin. The pathogenesis of an adenomyoma is discussed in the section on adenomyomatosis (see earlier). The lesion is usually approximately 15 mm in size, and its bulk is confined to the muscular wall of the gallbladder.102

Inflammatory Polyps

Inflammatory polyps are small sessile lesions that consist of granulation and fibrous tissue infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells. The average size is 5 to 10 mm. A solitary polyp is found in 50% of cases, and two to five polyps are found in the remainder.102 When discovered at the time of cholecystectomy, an inflammatory polyp is almost always an incidental finding.

Adenomas

In light of the high frequency of adenomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, gallbladder adenomas are surprisingly uncommon. Their frequency in resected gallbladder specimens is only about 0.15%.105

Adenomas are typically solitary, pedunculated masses from 5 to 20 mm in diameter. They may occur anywhere in the gallbladder. When multiple, as they are in approximately one third of cases, two to five polyps are usually present. Histologically, they are classified as either papillary or nonpapillary. The former type consists of a branching, tree-like skeleton of connective tissue covered with tall columnar cells, whereas the latter consists of a proliferation of glands encased by a fibrous stroma. On rare occasions, the entire gallbladder mucosa may undergo adenomatous transformation that results in innumerable tiny mucosal polyps termed multicentric papillomatosis. Notably, gallstones are present in half of cases of adenomatous polyps.102

Unlike the colon, in which adenomas are much more common than adenocarcinomas, the gallbladder is affected less commonly by adenomas than by carcinomas (by a 1 : 4 ratio). The frequency of progression from adenoma to adenocarcinoma is not well defined. In a series of more than 1600 consecutive cholecystectomies from Japan, 18 of the operated patients were found to have gallbladder adenomas.106 Seven of the adenomas contained foci of carcinoma. In the same series, 79 cases of invasive carcinoma were found; 15 (19%) of the lesions were thought to have residual adenomatous tissue within the cancer, suggesting that the initial lesion may have been an adenoma. Notably, all the adenomas that contained foci of carcinoma were larger than 12 mm, a finding that suggests that large adenomas may represent premalignant lesions.

Miscellaneous Polyps

Although a wide variety of benign lesions may manifest as polyps in the gallbladder, these lesions are rare. Fibromas, leiomyomas, and lipomas of the gallbladder are extraordinarily rare, particularly considering how commonly they are found elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract. Neurofibromas, carcinoids,107 and heterotropic gastric glands occur even less frequently.108 Taken together, the combined frequency of nonadenomatous neoplastic polyps of the gallbladder is considerably less than 1 per 1000 resected specimens.102

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

Polyps of the gallbladder typically do not cause symptoms. They are often noted as an incidental finding during cholecystectomy for gallstones or by imaging studies performed for other indications. In the exceptional case in which a polyp (without gallstones) is identified ultrasonographically or radiographically because of symptoms, the clinical symptomatology may resemble that of biliary pain, although classic features (e.g., intense epigastric or right upper quadrant pain starting suddenly, rising in intensity over a 15-minute period, and continuing at a steady plateau for several hours before slowly subsiding) may be absent. Rare instances of acute acalculous cholecystitis and even hemobilia have been ascribed to benign gallbladder polyps.109

The histologic types of gallbladder polyps cannot be distinguished on clinical grounds alone.99 Nor do ultrasonographic and cholecystographic findings predict histology reliably (Fig. 67-8).91 The sensitivity of conventional ultrasonography may be as high as 80% for detecting polyps greater than 10 mm in diameter, but its accuracy in characterizing the type of polyp may be as low as 20%.110 Endoscopic ultrasonography is a more sensitive and specific method for diagnosing gallbladder polyps. One study comparing conventional and endoscopic ultrasonography found that the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography for differentiating polyp types exceeded 90%.111 Several studies have shown that an endoscopic ultrasonographic scoring system that incorporates the size, number, shape, and echogenicity of polyps and polyp margins may predict the neoplastic potential of gallbladder polyps.111–113 Several cases in which preoperative 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET accurately predicted the presence of malignant tumor of the gallbladder in patients with gallbladder polyps have been reported.114

Other studies have evaluated clinical predictors of malignancy. Aside from polyp size (>10 mm), patient age greater than 60 years is the strongest predictor of neoplastic disease. The presence of concurrent gallstones is also associated with a higher risk of malignancy.115 Single polyps and symptomatic polyps may be more likely to be malignant than multiple polyps and asymptomatic polyps, respectively.

NATURAL HISTORY

The few studies that have attempted to define the natural history of untreated gallbladder polyps highlight the benign nature of most polyps and support a “watch and wait” approach in most cases.116 On the basis of records at the Mayo Clinic, one study identified approximately 200 patients in whom cholecystograms demonstrated gallbladder polyps and immediate cholecystectomy was not performed.117 After 15 years of follow-up, symptoms sufficient to warrant surgery developed in fewer than 10% of the patients, and none of the patients available for follow-up had evidence of gallbladder cancer.

One group of investigators performed annual or semiannual ultrasound for a 5-year period on 109 patients with polyps smaller than 10 mm. During this time, gallbladder cancer developed in no patient, and the polyp exhibited no growth in more than 88% of patients.118

Another study identified 224 patients with gallbladder polyps, 95% of which were predicted to be cholesterol polyps on the basis of the ultrasonographic appearance and the remainder of which were classified as “polypoid lesions of uncertain benignity.”119 After an average follow-up of 9 months, all the polyps thought initially to be benign remained the same size or were proved to be benign at resection. Two thirds of the polypoid lesions in which a benign nature was uncertain were found to be adenomas or carcinomas when resected. These findings suggest that although most gallbladder polyps are benign, high-risk polyps often have an identifiable characteristic such as larger size.

TREATMENT

The likelihood of malignancy is correlated with polyp size. Polyps less than 10 mm in diameter are unlikely to be cancerous and generally do not require intervention in the absence of symptoms. Because polyps larger than 10 mm have a greater likelihood of being cancerous, elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be considered in acceptable surgical candidates.120–122 In a patient who is a poor surgical risk with a polyp larger than 10 mm, periodic monitoring for polyp growth (perhaps every 6 to 12 months) with ultrasound or endoscopic ultrasound may be reasonable.120,122 Polyps larger than 18 mm in diameter pose a significant risk of malignancy and should be resected if possible. One study found that lesions of this size often contain advanced, invasive cancer that involves the serosal surface of the gallbladder and requires a more extensive dissection than can be accomplished by laparoscopy.123 As a result, the investigators advocate open cholecystectomy for these large polypoid lesions of the gallbladder.

The 10-mm cut-off rule for following gallbladder polyps expectantly may not apply to patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis, in whom the risk of malignancy in polypoid lesions of the gallbladder may be as high as 60%.124 In this high-risk population, cholecystectomy for polyps smaller than 10 mm may be justifiable. In low-risk populations, such as asymptomatic patients with small, presumably benign polyps, periodic surveillance for polyp growth may be prudent. One group of investigators recommends conventional ultrasonographic evaluation every 3 to 6 months in the immediate post-diagnostic period to exclude a rapidly growing tumor, but less frequent or no investigation after 1 to 2 years of stability in polyp size.125

Akatsu T, Aiura K, Shimazu M, et al. Can endoscopic ultrasonography differentiate nonneoplastic from neoplastic gallbladder polyps? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:416-21. (Ref 79.)

Albores-Saavedra J, Shukla D, Carrick K, Henson D. In situ and invasive adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder extending into or arising from Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses: A clinicopathologic study of 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:621-8. (Ref 89.)

Boulton R, Adams D. Gallbladder polyps: When to wait and when to act. Lancet. 1997;349:817-18. (Ref 116.)

Hansel S, DiBaise J. Gallbladder dyskinesia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:78-84. (Ref 6.)

Kalliafas S, Ziegler DW, Flancbaum L, Choban PS. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: Incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and outcome. Am Surg. 1998;64:471-5. (Ref 31.)

Kmiot WA, Perry EP, Donovan IA, et al. Cholesterolosis in patients with chronic acalculous biliary pain. Br J Surg. 1994;81:112-15. (Ref 74.)

Laurila J, Syrajala H, Laurila P. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in critically ill patients. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2004;48:986-91. (Ref 52.)

Lee K, Wong J, Li J, Lai P. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Am J Surg. 2004;188:186-90. (Ref 125.)

Mirvis SE, Vainright JR, Nelson AW, et al. The diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis: A comparison of sonography, scintigraphy, and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:1171-5. (Ref 44.)

Rastogi A, Slivka A, Moser A, Wald A. Controversies concerning pathophysiology and management of acalculous biliary-type abdominal pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1391-401. (Ref 16.)

Terzi C, Sökmen, Seckin S, et al. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: report of 100 cases with special reference to operative indications. Surgery. 2000;127:622-7. (Ref 115.)

Weedon D. Adenomyomatosis. In: Pathology of the Gallbladder. New York: Masson; 1984:185-94. (Ref 80.)

Weedon D. Cholesterolosis. In: Pathology of the Gallbladder. New York: Masson; 1984:161-5. (Ref 60.)

Yap L, Wycherley AG, Morphett AD, Toouli J. Acalculous biliary pain: Cholecystectomy alleviates symptoms in patients with abnormal cholescintigraphy. Gastroenterology. 1991;3:786-93. (Ref 5.)

1. Traverso LW, Lonborg R, Pettingell K, Fenster LF. Utilization of cholecystectomy—a prospective outcome analysis in 1325 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:1-5.

2. Fenster LF, Lonborg R, Thirlby RC, Traverso LW. What symptoms does cholecystectomy cure? Insights from an outcomes measurement project and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1995;169:533-8.

3. Festi D, Sottili S, Colecchia A, et al. Clinical manifestations of gallstone disease: Evidence from the multicenter Italian study on cholelithiasis (MICOL). Hepatology. 1999;30:839-46.

4. Corraziari E, Shaffer EA, Hogan WJ, et al. Functional disorders of the biliary tract and pancreas. In: Drossman DA, editor. Rome II: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. McLean, VA: Degnon; 2000:433-481.

5. Yap L, Wycherley AG, Morphett AD, Toouli J. Acalculous biliary pain: Cholecystectomy alleviates symptoms in patients with abnormal cholescintigraphy. Gastroenterology. 1991;3:786-93.

6. Hansel S, DiBaise J. Gallbladder dyskinesia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:78-84.

7. Venkataramani A, Strong RM, Anderson DS, et al. Abnormal duodenal bile composition in patients with acalculous chronic cholecystitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;3:434-41.

8. Herrera BA, Canelles GP, Medina CE, et al. [Cholecystectomy: A choice technique in biliary microlithiasis] [Spanish]. An Med Interna. 1995;12:111-14.

9. Susann PW, Sheppard F, Baloga AJ. Detection of occult gallbladder disease by duodenal drainage collected endoscopically: A clinical and pathologic correlation. Am Surg. 1985;51:162-5.

10. Porterfield G, Cheung LY, Berenson M. Detection of occult gallbladder disease by duodenal drainage. Am J Surg. 1977;134:702-4.

11. Halverson JD, Garner BA, Siegel BA, et al. The use of hepatobiliary scintigraphy in patients with acalculous biliary pain. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1305-7.

12. Chen P, Nimeri A, Pham Q, et al. The clinical diagnosis of chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Surgery. 2001;130:578-83.

13. Moskovitz M, Min TC, Gavaler JS. The microscopic examination of bile in patients with biliary pain and negative imaging tests. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:329-33.

14. Kakhi V, Zkavi S, Davoudi Y. Normal values of gallbladder ejection fraction using 99m Tc-sestamibi scintigraphy after a fatty meal formula. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2007;16:157-61.

15. Ziessman HA. Cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy: Victim of its own success? J Nucl Med. 1999;40:2038-42.

16. Rastogi A, Slivka A, Moser A, Wald A. Controversies concerning pathophysiology and management of acalculous biliary-type abdominal pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1391-401.

17. Goncalves RM, Harris JA, Rivera DE. Biliary dyskinesia: Natural history and surgical results. Am Surg. 1998;64:493-7.

18. Ozden N, DiBaise J. Gallbladder ejection fraction and symptom outcome in patients with acalculous biliary-like pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:890-7.

19. Barrett DS, Chadwick SJ, Fleming JA. Acalculous cholecystitis—a misnomer. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:664.

20. Barie PS, Fischer E. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:232-44.

21. Gora-Gebka M, Liberek A, Bako W, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis of viral etiology—a rare condition in children? J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:25-7.

22. Savoca PE, Longo WE, Zucker KA, et al. The increasing prevalence of acalculous cholecystitis in outpatients: Results of a 7-year study. Ann Surg. 1990;211:433-7.

23. Wiboltt KS, Jeffrey RBJr. Acalculous cholecystitis in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:519-24.

24. Nash JA, Cohen SA. Gallbladder and biliary tract disease in AIDS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1997;26:323-35.

25. Winkler AP, Gleich S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis caused by Salmonella typhi in an 11-year-old. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:125-8.

26. Merchant S, Falsey A. Staphylococcus aureus cholecystitis: Report of three cases with review of literature. Yale J Biol Med. 2002;75:285-91.

27. Cappell MS. Hepatobiliary manifestations of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1-15.

28. Kamimura T, Mimori A, Takeda A, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and review of the literature. Lupus. 1998;7:361-3.

29. Parithivel VS, Gerst PH, Banerjee S, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in young patients without predisposing factors. Am Surg. 1999;65:366-8.

30. Ganpathi I, Diddapur R, Eugene H, Karim M. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: Challenging the myths. HPB (Oxford). 2007;9:131-4.

31. Kalliafas S, Ziegler DW, Flancbaum L, Choban PS. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: Incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and outcome. Am Surg. 1998;64:471-5.

32. Lee SP. Pathogenesis of biliary sludge. Hepatology. 1990;12:200-3S.

33. Warren BL. Small vessel occlusion in acute acalculous cholecystitis. Surgery. 1992;111:163-8.

34. Hakala T, Nuutinen PJ, Ruokonen ET, Alhava E. Microangiopathy in acute acalculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1249-52.

35. Becker CG, Dubin T, Glenn F. Induction of acute cholecystitis by activation of factor XII. J Exp Med. 1980;151:81-90.

36. Kaminski DL, Andrus CH, German D, Deshpande YG. The role of prostanoids in the production of acute acalculous cholecystitis by platelet-activating factor. Ann Surg. 1990;212:455-61.

37. Kaminski DL, Feinstein WK, Deshpande YG. The production of experimental cholecystitis by endotoxin. Prostaglandins. 1994;47:233-45.

38. Laurila J, Karttunen T, Koivukangas V, et al. Tight junction proteins in gallbladder epithelium: Different expression in acute acalculous and calculous cholecystitis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;11:835-42.

39. Claesson BE. Microflora of the biliary tree and liver-clinical correlates. Dig Dis. 1996;4:93-118.

40. Al-Azzawi H, Nakeeb A, Saxena R, et al. Cholecystosteatosis: An explanation for increased cholecystectomy rates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:835-42.

41. Cornwell E, Rodriguez A, Mirvis SE, Shorr RM. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in critically injured patients: Preoperative diagnostic imaging. Ann Surg. 1989;210:52-5.

42. Johnson LB. The importance of early diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:197-203.

43. Boland GW, Lee MJ, Leung J, Mueller PR. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in critically ill patients: Early response and final outcome in 82 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:339-42.

44. Mirvis SE, Vainright JR, Nelson AW, et al. The diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis: A comparison of sonography, scintigraphy, and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:1171-5.

45. Laing FC, Federle MP, Jeffrey RB, Brown TW. Ultrasonic evaluation of patients with acute right upper quadrant pain. Radiology. 1981;140:449-55.

46. Helbich TH, Mallek R, Madl C, et al. Sonomorphology of the gallbladder in critically ill patients: Value of a scoring system and follow-up examinations. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:129-34.

47. Blankenberg F, Wirth R, Jeffrey RJ, et al. Computed tomography as an adjunct to ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:149-53.

48. Shuman WP, Rogers JV, Rudd TG, et al. Low sensitivity of sonography and cholescintigraphy in acalculous cholecystitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:531-4.

49. Schneider PB. Acalculous cholecystitis: A case with variable cholescintigram. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:64-5.

50. Prevot N, Mariat G, Mahul P, et al. Contribution of cholescintigraphy to the early diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis in intensive-care-unit patients. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:1317-25.

51. Flancbaum L, Choban PS, Sinha R, Jonasson O. Morphine cholescintigraphy in the evaluation of hospitalized patients with suspected acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1994;220:25-31.

52. Laurila J, Syrajala H, Laurila P. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in critically ill patients. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2004;48:986-91.

53. Sosna J, Copel L, Kane RA. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cholecystostomy: Update on technique and clinical application. Surg Technol Int. 2003;11:135-9.

54. Shirai Y, Tsukada K, Kawaguchi H, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1440-2.

55. Kim KH, Sung CK, Park BK, et al. Percutaneous gallbladder drainage for delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2000;179:111-13.

56. Tierney S, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Physiology and pathophysiology of gallbladder motility. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:1267-90.

57. Johlin FC, Neil GA. Drainage of the gallbladder in patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis by transpapillary endoscopic cholecystostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:645-51.

58. Brugge WR, Friedman LS. A new endoscopic procedure provides insight into an old disease: Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1718-20.

59. Sitzmann J, Pitt H, Steinborn P. Cholecystokinin prevents parenteral nutrition induced biliary sludge in humans. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:25-31.

60. Weedon D. Cholesterolosis. In: Pathology of the Gallbladder. New York: Masson; 1984:161-5.

61. Jutras JA, Longtin JM, Levesque HP. Hyperplastic cholecystoses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1960;83:795-827.

62. Feldman M, Feldman MJr. Cholesterolosis of the gallbladder: An autopsy study of 165 cases. Gastroenterology. 1954;27:641-8.

63. Elfving G, Palmu A, Asp K. Regional distribution of hyperplastic cholecystoses in the gallbladder wall. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn. 1969;58:204-7.

64. Mendez-Sanchez N, Tanimoto M, Cobos, et al. Cholesterolosis is not associated with high cholesterol levels in patients with and without gallstone disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:518-21.

65. Dittrick G, Thompson J, Campos S, et al. Gallbladder pathology in morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2005;15:238-42.

66. Sahlin S, Stahlberg D, Einarsson K. Cholesterol metabolism in liver and gallbladder mucosa of patients with cholesterolosis. Hepatology. 1995;21:1269-75.

67. Juvonen T, Savolainen MJ, Kairaluoma MI, et al. Polymorphisms at the apoB, apoA-I, and cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene loci in patients with gallbladder disease. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:804-12.

68. Behar J, Lee KY, Thompson WR, Biancani P. Gallbladder contraction in patients with pigment and cholesterol stones. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1479-84.

69. Jacyna MR, Ross PE, Bakar MA, et al. Characteristics of cholesterol absorption by human gallbladder: Relevance to cholesterolosis. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:524-9.

70. Tilvis RS, Aro J, Strandberg TE, et al. Lipid composition of bile and gallbladder mucosa in patients with acalculous cholesterolosis. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:607-15.

71. Satoh H, Koga A. Fine structure of cholesterolosis in the human gallbladder and the mechanism of lipid accumulation. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;39:14-21.

72. Braghetto I, Antezana C, Hurtado C, Csendes A. Triglyceride and cholesterol content in bile, blood, and gallbladder. Am J Surg. 1988;156:26-8.

73. Watanabe F, Hanai H, Kaneko E. Increased acyl CoA-cholesterol ester acyltransferase activity in gallbladder mucosa in patients with gallbladder cholesterolosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1518-23.

74. Kmiot WA, Perry EP, Donovan IA, et al. Cholesterolosis in patients with chronic acalculous biliary pain. Br J Surg. 1994;81:112-15.

75. Parrilla PP, Garcia OD, Pellicer FE, et al. Gallbladder cholesterolosis: An aetiological factor in acute pancreatitis of uncertain origin. Br J Surg. 1990;77:735-6.

76. Miquel JF, Rollan A, Guzman S, Nervi F. Microlithiasis and cholesterolosis in “idiopathic” acute pancreatitis [letter; comment]. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:2188-90.

77. Neoptolemos JP, Isgar B. Relationship between cholesterolosis and pancreatitis. HPB Surg. 1991;3:217-20.

78. Price RJ, Stewart ET, Foley WD, Dodds WJ. Sonography of polypoid cholesterolosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139:1197-8.

79. Akatsu T, Aiura K, Shimazu M, et al. Can endoscopic ultrasonography differentiate nonneoplastic from neoplastic gallbladder polyps? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:416-21.

80. Weedon D. Adenomyomatosis. In: Pathology of the Gallbladder. New York: Masson; 1984:185-94.

81. Ram MD, Midha D. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. Surgery. 1975;78:224-9.

82. Shepard VD, Walters W, Dockerty MB. Benign neoplasms of the gallbladder. Arch Surg. 1942;45:1-18.

83. Young TE. So-called adenomyoma of the gallbladder. Am J Clin Pathol. 1959;31:423-7.

84. Wang HP, Wu MS, Lin CC, et al. Pancreaticobiliary diseases associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:184-9.

85. Tanno S, Obara T, Maguchi H, et al. Association between anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union and adenomyomatosis of the gall-bladder. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:175-80.

86. Kurihara K, Mizuseki K, Ninomiya T, et al. Carcinoma of the gallbladder arising in adenomyomatosis. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993;43:82-5.

87. Aldridge MC, Gruffaz F, Castaing D, Bismuth H. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: A premalignant lesion? Surgery. 1991;109:107-10.

88. Ootani T, Shirai Y, Tsukada K, Muto T. Relationship between gallbladder carcinoma and the segmental type of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. Cancer. 1992;69:2647-52.

89. Albores-Saavedra J, Shukla D, Carrick K, Henson D. In situ and invasive adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder extending into or arising from Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses: A clinicopathologic study of 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:621-8.

90. Berk RN, van der Vegt JH, Lichtenstein JE. The hyperplastic cholecystoses: Cholesterolosis and adenomyomatosis. Radiology. 1983;146:593-601.

91. Cooperberg P, Gibney R. Imaging of the gallbladder. Radiology. 1987;163:605-13.

92. Raghavendra BN, Subramanyam BR, Balthazar EJ, et al. Sonography of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1983;146:747-52.

93. Hwang JI, Chou YH, Tsay SH, et al. Radiologic and pathologic correlation of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:73-7.

94. Yoshimitsu K, Honda H, Jimi M, et al. MR diagnosis of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder and differentiation from gallbladder carcinoma: Importance of showing Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1535-40.

95. Clouston JE, Thorpe RJ. Case report-CT findings in adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. Australas Radiol. 1991;35:86-7.

96. Miyake H, Aikawa H, Hori Y, et al. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder with subserosal fatty proliferation: CT findings in two cases. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:21-3.

97. Yoshimitsu K, Honda H, Aibe H, et al. Radiologic diagnosis of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: Comparative study among MRI, helical CT and transabdominal US. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:843-50.

98. Maldjian P, Ghesani N, Ahmed S, Liu Y. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: Another cause for “hot” gallbladder on 18F-FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:W36-8.

99. Nahrwold DL. Benign tumors and pseudotumors of the biliary tract. In: Way LW, Pellegrini CA, editors. Surgery of the Gallbladder and Bile Ducts. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1987:459-69.

100. Okamoto M, Okamoto H, Kitahara F, et al. Ultrasonographic evidence of association of polyps and stones with gallbladder cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:446-50.

101. Jorgensen T, Jensen KH. Polyps in the gallbladder: A prevalence study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:281-6.

102. Weedon D. Benign mucosal polyps. In: Pathology of the Gallbladder. New York: Masson; 1984:195-9.

103. Takii Y, Shirai Y, Kanehara H, Hatakeyama K. Obstructive jaundice caused by a cholesterol polyp of the gallbladder: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1994;24:1104-6.

104. Selzer DW, Dockerty MB, Stauffer MH, Priestly JT. Papillomas (so-called) in the non-calculous gallbladder. Am J Surg. 1962;103:472-6.

105. Swinton NW, Becker WF. Tumors of the gallbladder. Surg Clin North Am. 1948;28:669-72.

106. Kozuka S, Tsubone M, Yasui A, Hachisuka K. Relation of adenoma to carcinoma in the gallbladder. Cancer. 1982;50:2226-34.

107. Tanaka K, Iida Y, Tsutsumi Y. Pancreatic polypeptide-immunoreactive gallbladder carcinoid tumor. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1992;42:115-18.

108. Vallera DU, Dawson PJ, Path FR. Gastric heterotopia in the gallbladder: Case report and review of literature. Pathol Res Pract. 1992;188:49-52.

109. Cappell MS, Marks M, Kirschenbaum H. Massive hemobilia and acalculous cholecystitis due to benign gallbladder polyp. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1156-61.

110. Akyürek N, Salman B, Irkörücü O, et al. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of true gallbladder polyps: The contradiction in the literature. HPB (Oxford). 2005;7:155-8.

111. Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Yamato T. Endoscopic ultrasonography for differential diagnosis of polypoid gallbladder lesions: Analysis in surgical and follow-up series. Gut. 2000;46:250-4.

112. Azuma T, Yoshikawa T, Araida T, Takasaki K. Differential diagnosis of polypoid lesions on the gallbladder by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Surg. 2001;181:65-70.

113. Choi WB, Lee SK, Kim MH, et al. A new strategy to predict the neoplastic polyps of the gallbladder based on a scoring system using EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:372-9.

114. Koh T, Taniguchi H, Kunishima S, Tamagishi H. Possibility of differential diagnosis of small polypoid lesions in the gallbladder using FDG-PET. Clin Positron Imaging. 2000;3:213-18.

115. Terzi C, Sökmen, Seckin S, et al. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: Report of 100 cases with special reference to operative indications. Surgery. 2000;127:622-7.

116. Boulton R, Adams D. Gallbladder polyps: When to wait and when to act. Lancet. 1997;349:817-18.

117. Eelkema HH, Hodgson JR, Stauffer MH. Fifteen-year follow-up of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder diagnosed by cholecystography. Gastroenterology. 1962;42:144-7.

118. Moriguchi H, Tazawa J, Hayashi Y, et al. Natural history of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Gut. 1996;39:860-2.

119. Heyder N, Gunter E, Giedl J, et al. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder [German]. Deutsche Med Wochenschrift. 1990;115:243-7.

120. Mainprize KS, Gould SW, Gilbert JM. Surgical management of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Br J Surg. 2000;87:414-17.

121. Kubota K, Bandai Y, Otomo Y, et al. Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in treating gallbladder polyps. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:42-6.

122. Sheth S, Bedford A, Chopra S. Primary gallbladder cancer: Recognition of risk factors and the role of prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1402-10.

123. Kubota K, Bandai Y, Noie T, et al. How should polypoid lesions of the gallbladder be treated in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Surgery. 1995;117:481-7.

124. Karlsen T, Schrumpf E, Boberg K. Gallbladder polyps in primary sclerosing cholangitis: Not so benign. Current Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:395-9.

125. Lee K, Wong J, Li J, Lai P. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Am J Surg. 2004;188:186-90.