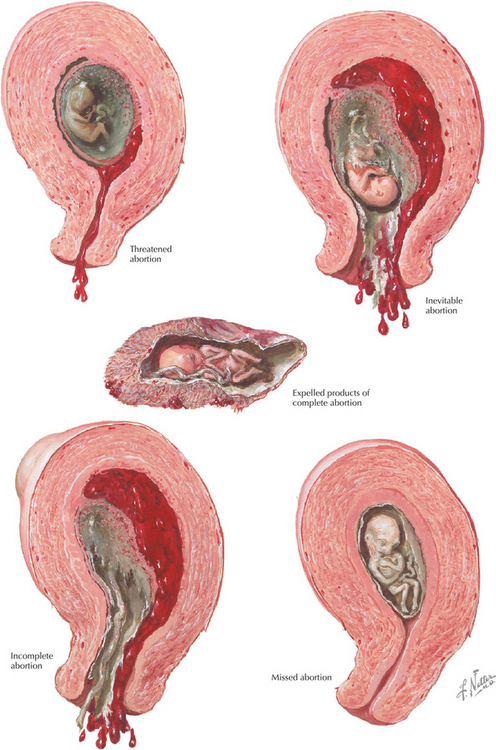

Chapter 7 Abortion

INTRODUCTION

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Workup and Evaluation

MANAGEMENT AND THERAPY

Nonpharmacologic

Drug(s) of Choice

FOLLOW-UP

MISCELLANEOUS

Batzofin JH, Fielding WI, Friedman EA. Effect of vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy on outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63:515.

Boklage CE. Survival probability of human conceptions from fertilization to term. Int J Fertil. 1990;35:75.

Bromley B, Harlow BL, Laboda LA, Benacerraf BR. Small sac size in the first trimester: a predictor of poor fetal outcome. Radiology. 1991;178:375.

Funderburk SJ, Guthrie D, Meldrum D. Outcome of pregnancies complicated by early vaginal bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;87:100.

Hakim-Elahie E, Tovell HM, Burnhill MS. Complications of first-trimester abortions: a report of 170,000 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:129.

Johannisson E, Oberholzer M, Swahn ML, Bygdeman M. Vascular changes in the human endometrium following the administration of the progesterone antagonist RU 486. Contraception. 1989;39:103.

Mackenzie WE, Holmes DS, Newton JR. Spontaneous abortion rate in ultrasonographically viable pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:81.

Schaff EA, Stadalius LS, Eisinger SH, Franks P. Vaginal misoprostol administered at home after mifepristone (RU486) for abortion. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:353.

Swahn ML, Bygdeman M. The effect of the antiprogestin RU 486 on uterine contractility and sensitivity to prostaglandin and oxytocin. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95:126.

Thom DH, Nelson LM, Vaughan TL. Spontaneous abortion and subsequent adverse birth outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:111.

Warburton D, Fraser FC. Spontaneous abortion risks in man: data from reproductive histories collected in a medical genetics unit. Am J Human Genet. 1964;16:1.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Medical management of abortion. ACOG Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians and gynecologists, Number 67. Washington, DC: ACOG, 2005.

Chen BA, Creinin MD. Contemporary management of early pregnancy failure. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:67.

Goldstein SR. Embryonic death in early pregnancy: a new look at the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:294.

Hogue CJR. Impact of abortion on subsequent fecundity. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1986;13:95.

Katz VL. Spontaneous and recurrent abortion, (CH16). In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, et al, editors. Comprehensive Gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier; 2007:359.

Kripke C. Expectant management vs. surgical treatment for miscarriage. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1125.

Poland BJ, Miller JR, Jones DC, Trimble BK. Reproductive counseling in patients who have had a spontaneous abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;127:685.

Smith RP. Gynecology in Primary Care. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997;99.

Stubblefield PG, Grimes DA. Septic abortion. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:310.

Tang OS, Ho PC. Clinical applications of mifepristone. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:655.