Chapter 6 Abnormalities of Menstruation

Physiological amenorrhoea

Menopause

The menopause is the cessation of menstruation (mean age 51 y) due to exhaustion of the supply of ovarian follicles. Oestrogen production therefore falls. This fall in oestrogen production is accompanied by a rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, which continues for a considerable time. In a proportion of women, menstruation ceases abruptly, but in many, the menstrual cycles alter. Frequently, they become shorter initially, but later they lengthen and tend to be irregular, before ceasing entirely. This phase is known as the menopause transition, and the final period is recognised only in retrospect, after 1 year of amenorrhoea. See Chapter 18.

Uterine and lower genital tract disorders

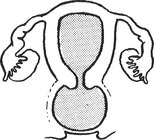

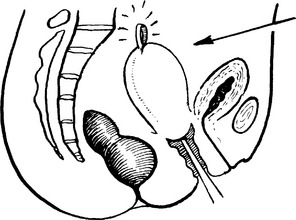

Imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum

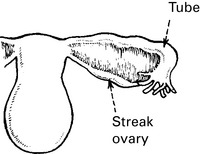

Ovarian disorders

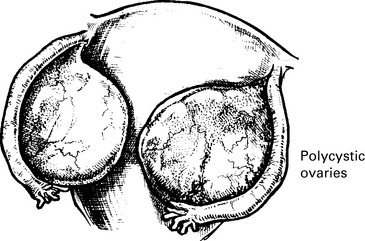

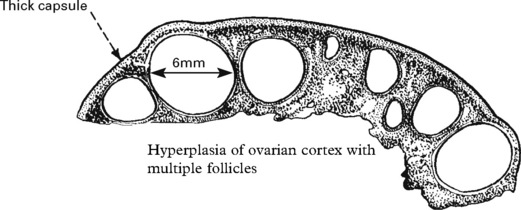

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

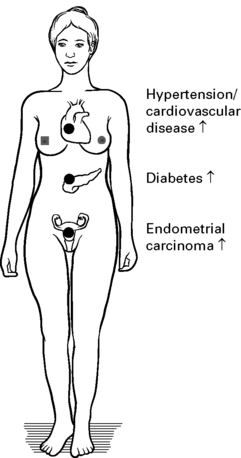

Long-term Effects of PCOS

Pituitary disorders

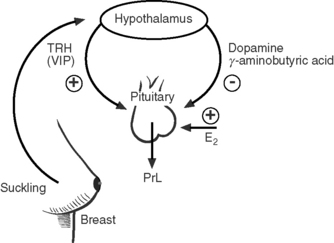

Hyperprolactinaemia

Aetiology

Hypothalamic disorders

Disorders of the hypothalamus result in hypogonoadotrophic hypogonadism, and hence amenorrhoea.

Causes

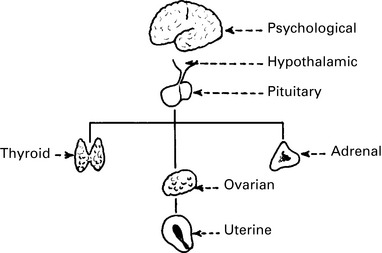

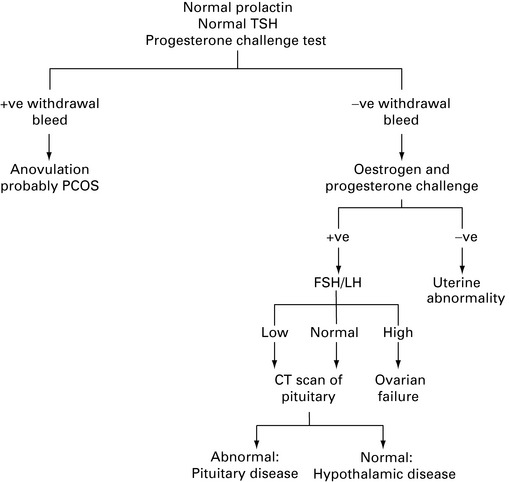

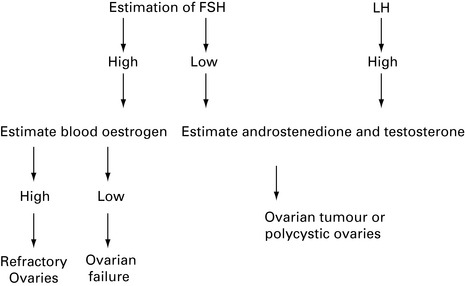

Investigation of amenorrhoea

The history should include the following:

A full physical examination should be performed. This should include the following:

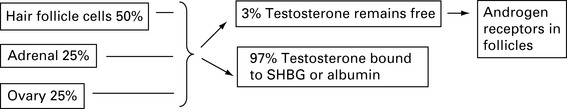

Hirsutism

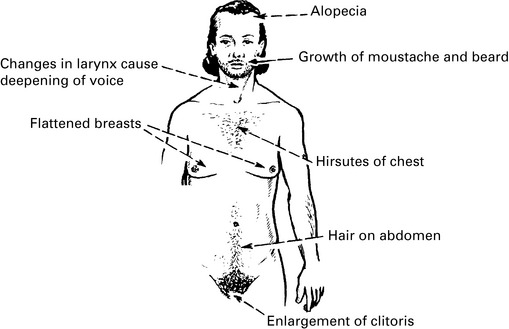

Virilisation

Masculinisation and virilisation are terms for extreme androgen effects.

Management of hirsutism

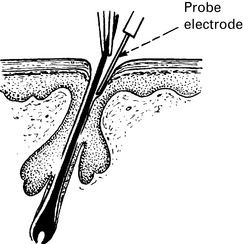

Local treatment

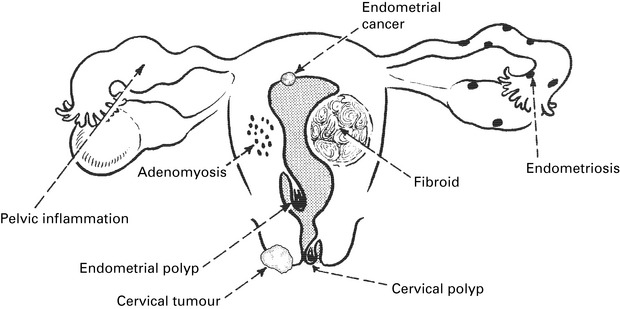

Menstrual disorder

Careful history taking is crucial in the assessment of menstrual disorder. Women with heavy regular bleeding and no additional symptoms of concern such as intermenstrual or postcoital bleeding are most likely to have dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Benign pathologies such as fibroids are a common cause of heavy menstrual bleeding. See Chapter 11.

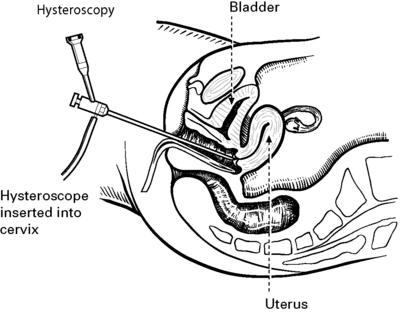

Investigation of the endometrium

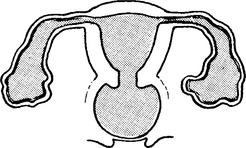

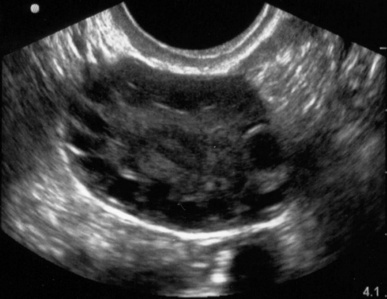

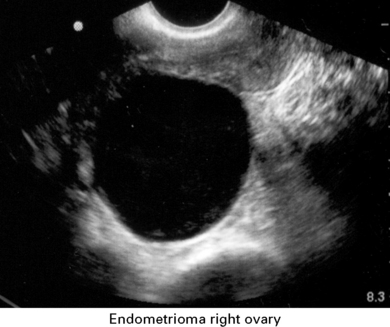

Transvaginal ultrasound scan This technique offers a close view of the uterus and adnexae.

Features noted during transvaginal scanning of the pelvis

Investigation of the Endometrium

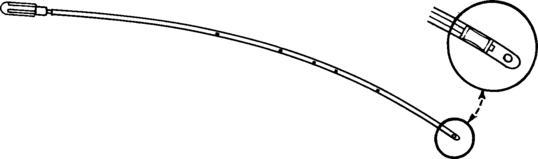

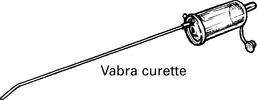

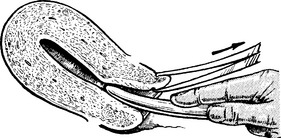

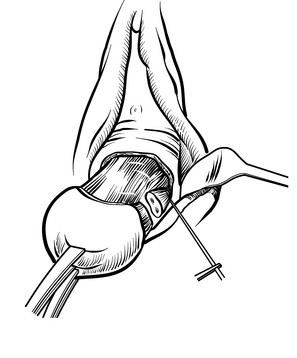

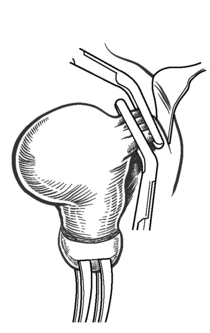

The main purpose of endometrial biopsy is to assess for endometrial hyperplasia or identify endometrial carcinoma. The risk of endometrial cancer in premenopausal women is very low, but biopsy should be performed for women over 45 with menstrual disorder. In women under 45, the need for biopsy (possibly with hysteroscopy) should be guided by other factors including intermenstrual or irregular bleeding, and scan findings. See page 201 hyperplastic conditions of the uterus.

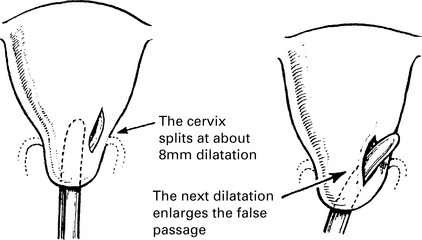

Investigations of Endometrium – Complications

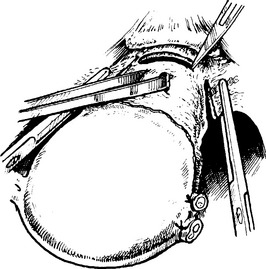

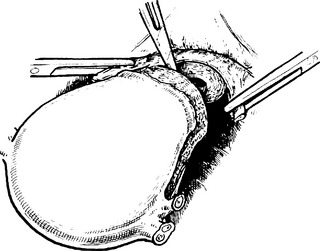

The volsellum forceps may tear the anterior lip of cervix if pulled on too forcibly.

Management of heavy menstrual bleeding

Medical management

Tranexamic Acid

Administration: tranexamic acid 1 g qds during menstruation.

Mode of action: inhibits clot breakdown within endometrial vasculature.

Side effects are usually mild but can include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea.

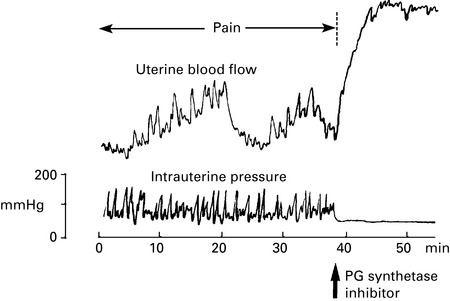

Prostaglandin Synthetase Inhibitors

Administration: for example mefenamic acid, 500 mg tid during menstruation.

Side effects can include, diarrhoea, rashes, thrombocytopenia and haemolytic anaemia.

Combined Contraceptive Pill

Administration: usual contraceptive regimen.

Mode of action: suppression of ovulation limits hormonal stimulation of the endometrium.

A reduction in menstrual loss can be seen in women both with and without menorrhagia.

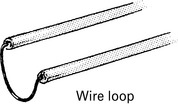

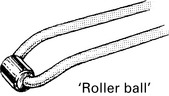

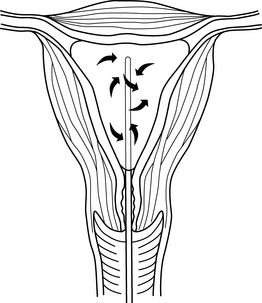

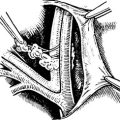

Endometrial Ablation Techniques

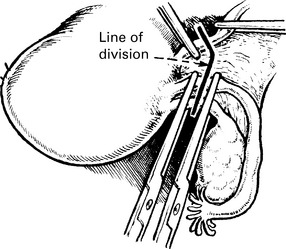

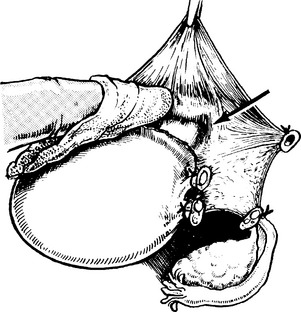

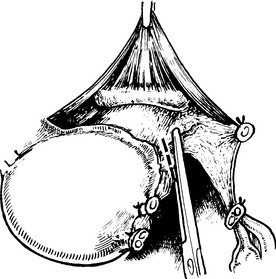

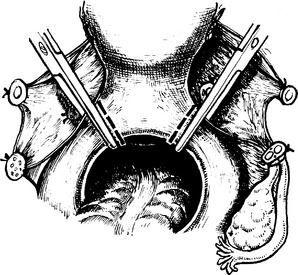

Total Hysterectomy (Removal ofuterus andcervix)

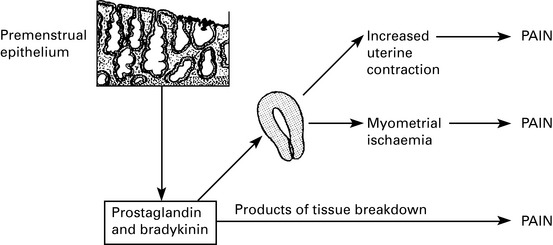

Dysmenorrhoea

Drug treatment

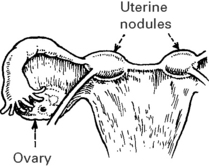

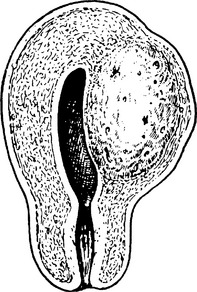

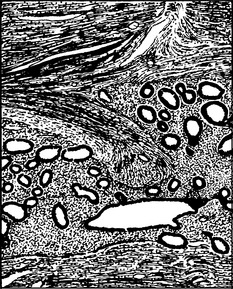

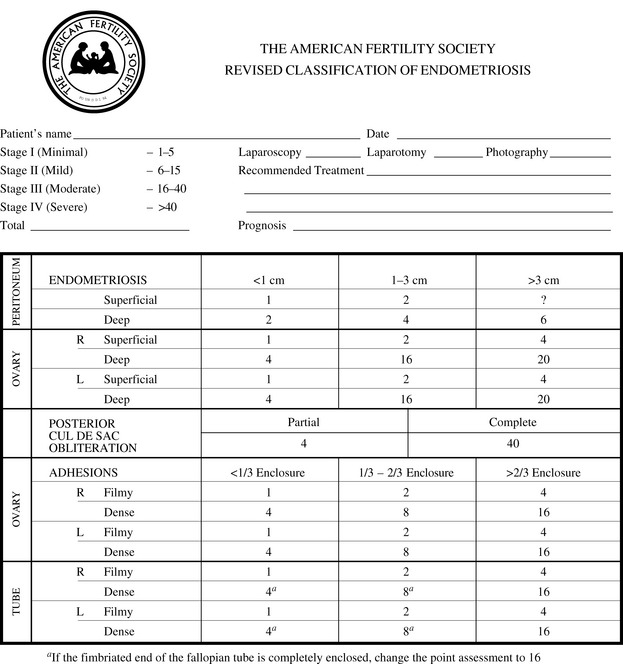

Endometriosis

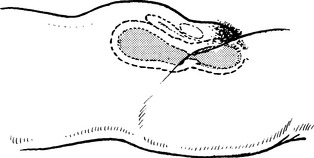

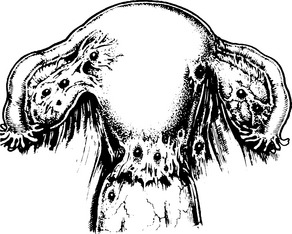

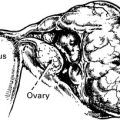

Pathology

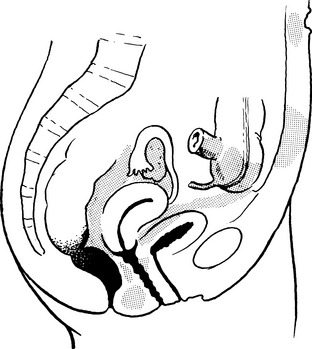

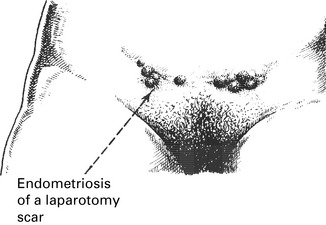

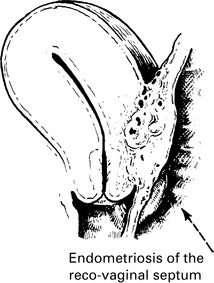

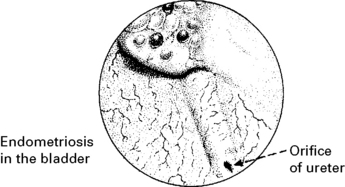

The commonest sites of these deposits are the following:

Symptomatology

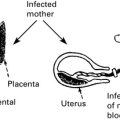

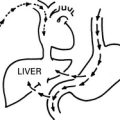

Histogenesis

Treatment

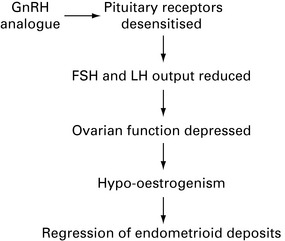

Medical Treatment

GnRH analogues are administered by depot injection or nasal spray. Their mode of action is shown above. These drugs are generally effective in treating symptoms caused by endometriosis; however, menopausal side effects are common. Add-back hormone replacement therapy will usually prevent the vast majority of vasomotor symptoms without stimulating endometriosis. These preparations are licensed for 6 months of use as there is concern that long-term use will increase the risk of osteoporosis and other effects of oestrogen deprivation.

Premenstrual syndrome

Mild – does not interfere with personal/social and professional life.

| Water retention | Pain | Autonomic reactions |

|---|---|---|

| Weight gain (up to 7lb) | Headache | Dizziness/faintness |

| Painful breasts | Backache | Cold sweats |

| Abdominal distension | Tiredness | Nausea/vomiting |

| Feeling of bloatedness | Muscle stiffness | Hot flushes |

| Mood changes | Loss of concentration | Miscellaneous |

| Tension | Forgetfulness | Feelings of suffocation |

| Irritability | Clumsiness | Chest pains |

| Depression | Difficulty in making decisions | Heart pounding |

| Crying spells | Poor sleeping | Numbness, tingling |