Chapter 2 ABNORMAL PREMENOPAUSAL UTERINE BLEEDING

In women of childbearing age, abnormal uterine bleeding includes any change in menstrual period frequency, duration, or amount of flow, as well as bleeding between cycles. A menstrual cycle of fewer than 21 days or more than 35 days is considered abnormal. Likewise, a menstrual flow of fewer than 2 days or more than 7 days is abnormal.

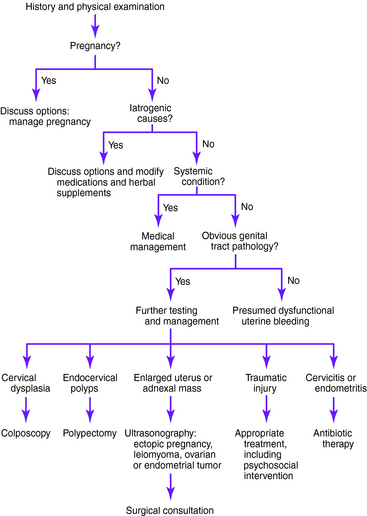

When abnormal uterine bleeding is evaluated (Figs. 2-1 and 2-2), it is important to make certain that the bleeding is not from a gastrointestinal or urinary source. Once it is clear that the bleeding is vaginal, pregnancy should be the first consideration in women of childbearing age. After pregnancy has been ruled out, iatrogenic causes of abnormal uterine bleeding should be considered. Medications linked to abnormal premenopausal uterine bleeding are outlined later in this chapter. After pregnancy and iatrogenic causes have been excluded, systemic conditions should be considered. These systemic causes and the suggested workup, outlined later in the chapter, include thyroid, hematologic, pituitary, hepatic, adrenal, and hypothalamic disorders.

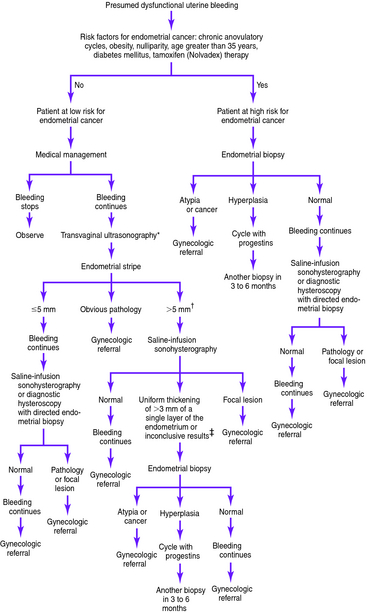

Figure 2-2. Presumed dysfunctional uterine bleeding in women of childbearing age: evaluation based on risk factors for endometrial cancer.*†‡

Of cases of endometrial carcinoma, 20% to 25% occur before menopause, and the risk of developing endometrial cancer increases with age. Thus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends endometrial evaluation in women aged 35 and older who have abnormal uterine bleeding. Endometrial evaluation is also recommended for patients younger than 35 who are at high risk for endometrial cancer. Women with vaginal bleeding who are younger than 35 years and have no identifiable risk factors for neoplasia can be assumed to have dysfunctional bleeding and treated accordingly. However, if bleeding continues in a patient at low risk for neoplasia despite medical management, endometrial evaluation is indicated.

Causes of Abnormal Premenopausal Uterine Bleeding

Adrenal hyperplasia and Cushing disease

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding

Estrogen-producing ovarian tumors

Hypothalamic suppression (stress, weight loss, excessive exercise)

Medications and herbal supplements

Pregnancy (intrauterine or ectopic)

Testosterone-producing ovarian tumors

Trauma (foreign body, abrasions, lacerations, sexual abuse or assault)

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

✓ General assessment of health and evaluation for obesity

✓ Search for evidence of eating disorders

✓ Thyroid examination for thyromegaly or thyroid tenderness

✓ Cardiovascular examination for tachycardia

✓ Skin examination for acne or acanthosis nigricans (signs of polycystic ovary syndrome or diabetes mellitus); also evaluation for bruising as a sign of coagulopathy and for jaundice

✓ Breast examination for galactorrhea

✓ Pelvic examination to evaluate for vulvar or vaginal lesions, signs of trauma, cervical polyps or dysplasia, cervical motion tenderness, uterine enlargement, uterine tenderness, or adnexal masses

Suggested Work-Up

| Pregnancy test | To evaluate for pregnancy |

| Pap smear | To evaluate for cervical dysplasia |

| Cultures for gonorrhea and chlamydia or nucleic acid amplification tests | If infection is suspected or the patient is at risk for sexually transmitted disease |

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) | If bleeding is heavy or prolonged and anemia is suspected |

| Endometrial biopsy or transvaginal ultrasonography or saline infusion sonohysterography or dilatation and curettage with hysteroscopy | Recommended in women aged 35 and older with abnormal uterine bleeding; also recommended for patients younger than 35 who are at high risk for endometrial cancer and for patients at low risk who continue bleeding abnormally despite medical management. See previous text for an explanation of benefits and drawbacks of each. |

Additional Work-Up

| Transvaginal ultrasonography | If there is uterine enlargement or an adnexal mass |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurement | If hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism is suspected |

| Prolactin level measurement | If pituitary adenoma or hyperprolactinemia is suspected |

| Blood glucose measurement | If diabetes mellitus is suspected |

| Liver function tests and prothrombin time measurement | If liver disease is suspected |

| CBC with measurements of platelet count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time | If coagulopathy is suspected |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), free testosterone, and 17α-hydroxyprogesterone measurements | If ovarian or adrenal tumor is suspected on the basis of signs of hyperandrogenism |

| von Willebrand factor measurement | If von Willebrand disease is suspected |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and TSH measurements | If edema is present |

| Colposcopy | If cervical dysplasia is found on Pap smear |

ACOG Community on Practice Bulletins—American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin: management of anovulatory bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;73:263-271.

Albers JR, Hull SH, Wesley RM. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1915-1926.

Apgar BS. Dysmenorrhea and dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Prim Care. 1997;24:161-178.

Chen BH, Giudice LC. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. West J Med. 1998;169:280-284.

Davidson KG, Dubinsky TJ. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the endometrium in postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:769-780.

Elford KJ, Spence JE. The forgotten female: pediatric and adolescent gynecological concerns and their reproductive consequences. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002;15:65-77.

Goldstein SR. Abnormal uterine bleeding: the role of ultrasound. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;44:901-910.

Goldstein SR, Zeltser I, Horan CK, et al. Ultrasonography-based triage for perimenopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:102-108.

Goodman A. Abnormal genital tract bleeding. Clin Cornerstone. 2000;3(1):25-35.

Kilbourn C, Richards C. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Postgrad Med. 2001;109:137-140.

Schrager S. Abnormal uterine bleeding associated with hormonal contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:2073-2080.

Smith-Bindman R, Kerlikowske K, Feldstein VA, et al. Endovaginal ultrasound to exclude endometrial cancer and other endometrial abnormalities. JAMA. 1998;280:1510-1517.

Tabor A, Watt HC, Wald NJ. Endometrial thickness as a test for endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:663-670.

* Transvaginal ultrasonography ideally is performed during the late proliferative stage.

† Some investigators consider an endometrial stripe of 7 to 8 mm or larger to be abnormal in premenopausal or perimenopausal women.

‡ These determinants are based on information from Goldstein SR, Zeltser I, Horan CK, Snyder JR, Schwartz LB. Ultrasonography-based triage for perimenopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:102-108.