Chapter 22 Abnormal labour (dystocia) and prolonged labour

These matters are discussed in this chapter.

ABNORMAL SHAPE OR SIZE OF THE PELVIS (THE PASSAGES)

The ideal obstetric pelvis is described on page 55. If any of the two main diameters, particularly of the pelvic brim, is reduced by 2 cm or more the pelvis is considered to be contracted. The shape of the pelvis may also be affected, for example the sacral curve may be replaced by a straight sacrum, or the pelvis may have been damaged by a serious accident.

CEPHALOPELVIC DISPROPORTION

ABNORMALITIES OF UTERINE ACTION

Labour will only progress normally if the contractile wave is propagated over the entire uterus in a triple descending gradient of activity (see p. 61).

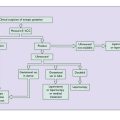

If the normal pattern of uterine activity fails to occur the progress of labour will be abnormal – usually prolonged. Until the 1940s, prolonged labour was considered to be caused by ‘uterine inertia’. Research since then has shown that several patterns of uterine activity may lead to delay in the birth of the child. The patterns are designated inefficient uterine activity and are divided into subgroups of abnormal uterine activity (Box 22.1). In some cases of labour the reverse occurs and the uterus is overactive, leading to a precipitate birth.

Inefficient uterine activity

Types of abnormal uterine action

Hypoactive states (uterine inertia)

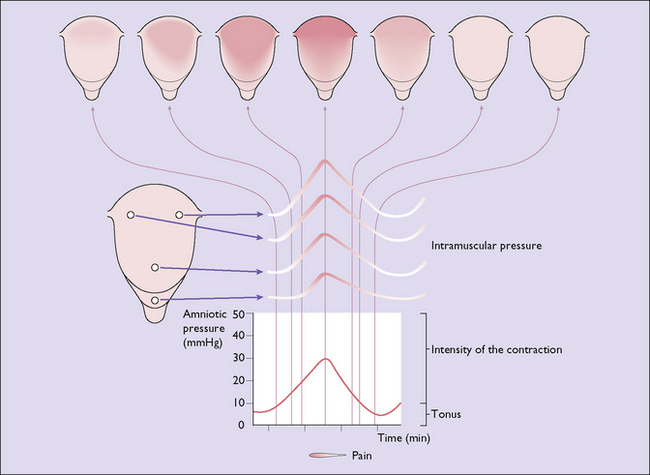

The uterine resting tone is low and the intensity of the contraction is reduced, with the result that only a feeble contractile wave is propagated (Fig. 22.1). The contractions occur at longer intervals than usual and do not cause the patient much distress.

Hyperactive incoordinate states (incoordinate uterine action)

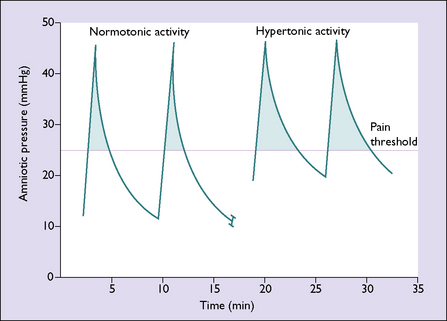

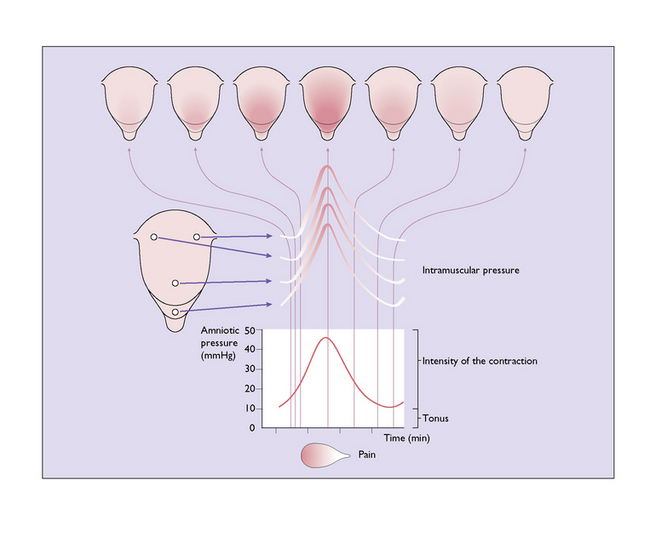

In normal labour the perception of pain is usually only reached when the uterine tone exceeds 25 mmHg. In hyperactive, incoordinate uterine activity the resting uterine tone is increased; in consequence, the pain threshold is reached earlier during the contraction and the pain persists for longer (Fig. 22.2). In spite of the strong contractions, cervical dilatation is slow because the triple gradient is reversed (Fig. 22.3).

The modern classification of inefficient uterine activity

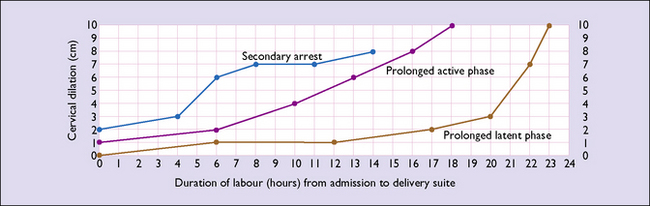

With the introduction of the partogram, a different classification has been developed (Fig. 22.4).

Management of inefficient uterine activity

Specific treatment

Prolonged latent phase

Having established that there is no major degree of CPD and that the woman is prepared to continue with the labour, two approaches are possible. In the first, no treatment beyond reassurance is given and the onset of the active phase is awaited. The alternative is to rupture the membranes and to set up an oxytocin infusion, which is increased incrementally (see p. 190). Abdominal palpation and a vaginal examination are made at 2-hourly intervals. There are no reliable data to show that the invasive approach shortens the duration of labour significantly.

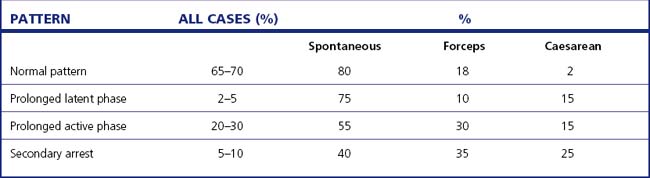

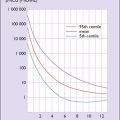

Outcome of labour

The outcome of labour treated in the above way has been reported in several studies, of which a representative is shown in Table 22.1. Since the date of that study the proportion of women delivered by caesarean section has increased but this has not led to a reduction in the perinatal mortality or morbidity, which is low.

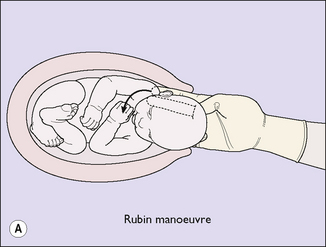

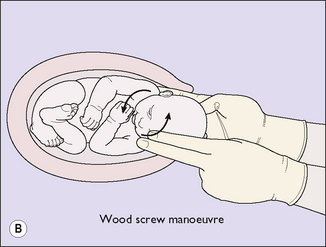

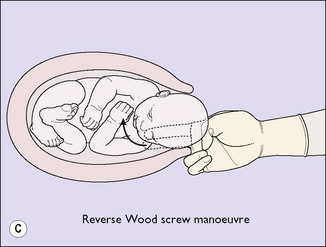

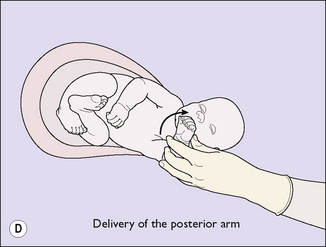

SHOULDER GIRDLE DYSTOCIA

Shoulder dystocia is frequently unanticipated as it can occur in the absence of known risk factors which include maternal diabetes, macrosomia, maternal obesity, prolonged second stage, a rotational operative vaginal delivery, or previous shoulder dystocia. The fetal head may be born but the head burrows back into the perineum (turtle sign) as the bisacromial diameter of the fetal shoulders fails to rotate to enter the transverse diameter of the pelvic brim. The baby must be delivered quickly or it will die (Fig. 22.5A–D). Shoulder girdle dystocia occurs in 1% of births and the delivery requires considerable experience: damage to the lower genital tract is a usual occurrence, and damage to the baby not uncommon. Most often the damage is to the brachial plexus, or the clavicle or humerus can be fractured. The latter two will heal without sequelae, but a brachial plexus palsy can be permanent. Only 50% of brachial plexus palsies actually follow shoulder dystocia and some 5% occur in association with a caesarean delivery which implies that at least some have an antepartum aetiology.

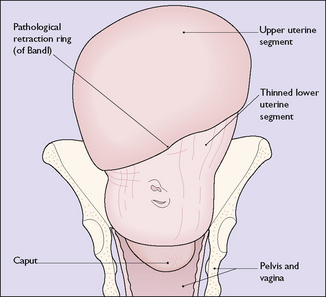

OBSTRUCTED LABOUR

During an obstructed labour, uterine contractions attempt to overcome the obstruction. In a first labour the uterus contracts strongly for a while and then, failing to overcome the obstruction, becomes hypoactive, developing secondary arrest. In contrast, if the obstruction occurs in a subsequent labour, the uterus continues to contract strongly in an attempt to push the fetus through the maternal pelvis. With each contraction there is some myometrial shortening (retraction), the upper uterine segment becoming progressively thicker and shorter, and the lower segment becoming progressively stretched and thinner. The junction between the two segments becomes obvious, forming a pathological retraction ring – Bandl’s ring (Fig. 22.6). The pathological retraction ring may be confused with a distended urinary bladder, but the oblique line is diagnostic. The patient becomes dehydrated, with a coated tongue and dry lips. She has tachycardia and concentrated urine, and faces the risk of a ruptured uterus at any time.

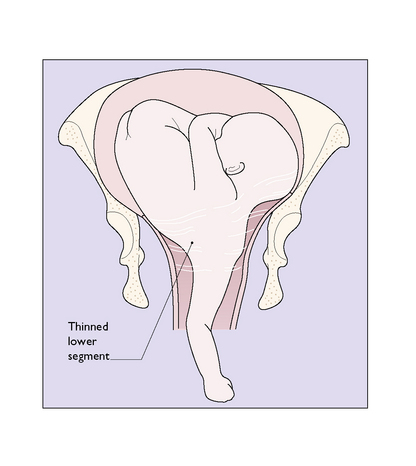

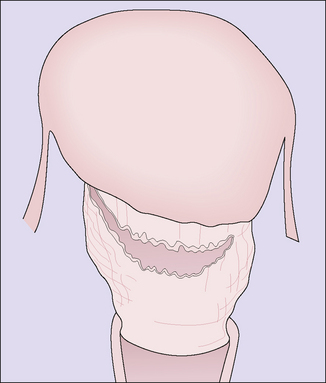

RUPTURE OF THE UTERUS

The end result of obstructed labour, unless intervention is made, is rupture of the uterus. Rupture may also occur in late pregnancy, when it may follow trauma to the uterus, or derive from a caesarean scar. In labour, as well as following an obstructed labour (Fig. 22.7), rupture of the uterus may be caused by the inappropriate use of oxytocics and the dehiscence of a caesarean section scar.

In cases of uterine rupture following trauma or obstructed labour, the rupture usually involves one or other lateral wall and extends into the upper uterine segment (Fig. 22.8).

CLASSIFICATION OF PELVIC ABNORMALITIES

Major defects of nutrition or environment

Rickets

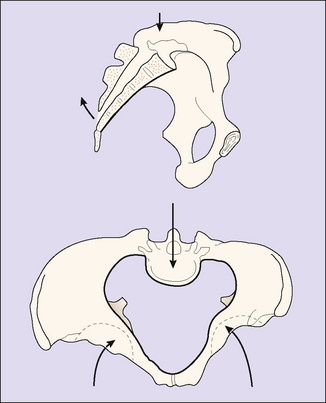

In a young child suffering from rickets the weight of the upper body presses down through the spine on to the softened pelvic bones. The sacral promontory is pushed forwards and downwards, and the sacrum itself pivots backwards. At the same time, the ligaments of the back draw the spinous process medially and the ilia flare outwards, as do the ischial tuberosities. In extreme cases the softened acetabula may be forced inwards. The main alteration in pelvic shape is a marked reduction of the anteroposterior measurement of the brim, with some irregular widening of the cavity (Fig. 22.9).

Osteomalacia

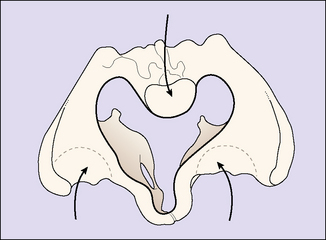

This is due to an acquired deficiency of calcium and, encountered in adult life, causes the same deformities as rickets, but is rare, except in certain inland parts of northern India and China (Fig. 22.10).

Disease or injury

Spinal

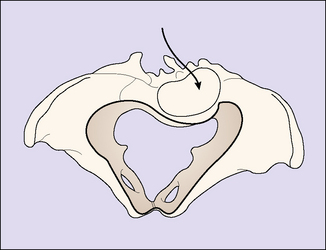

Kyphosis of the lower dorsal or lumbar region that started in childhood may alter the shape of the brim of the pelvis, as the weight of the body pushes the upper part of the sacrum backwards and the lower part forwards. The side walls of the pelvis converge, forming a funnel. In scoliosis the altered pressure distribution on the soft bones may cause bays on each side of the sacral promontory, rendering the shape of the brim asymmetrical (Fig. 22.11). Spondylolisthesis, which means the slipping forward of the fifth lumbar vertebra to project beyond the sacral promontory, is rare (Fig. 22.12).

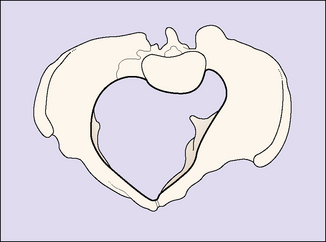

Congenital malformations

These include Naegele’s pelvis and Robert’s pelvis, and are due to the defective development of one or both sacral lateral masses, causing the sacrum to fuse with the ilium on one or both sides (Fig. 22.13). The high assimilation pelvis occurs when the fifth lumbar vertebra is fused to the sacrum, thus increasing the inclination of the pelvic brim. This hinders engagement of the fetal head.