Chapter 21 Abnormal fetal presentations

OCCIPITOPOSTERIOR PRESENTATIONS

In about 10% of pregnancies the fetal head enters the maternal pelvis with its occiput in one of the posterior segments of the pelvis (see Fig. 8.4, p. 70).

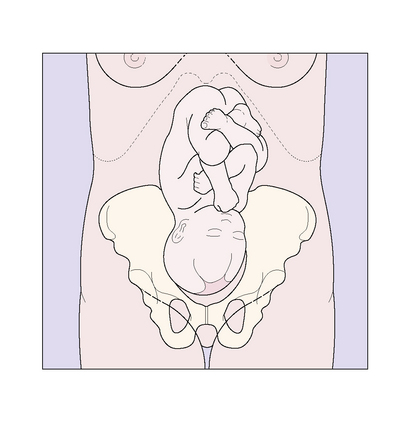

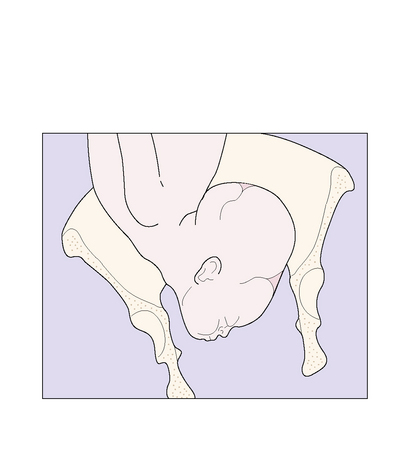

The diagnosis may be made on abdominal palpation when the fetal back is felt in one of the mother’s flanks, the fetal heart being loudest here (Fig. 21.1). In labour, vaginal examination provides more information, the occiput and the anterior fontanelle being identified (Fig. 21.2).

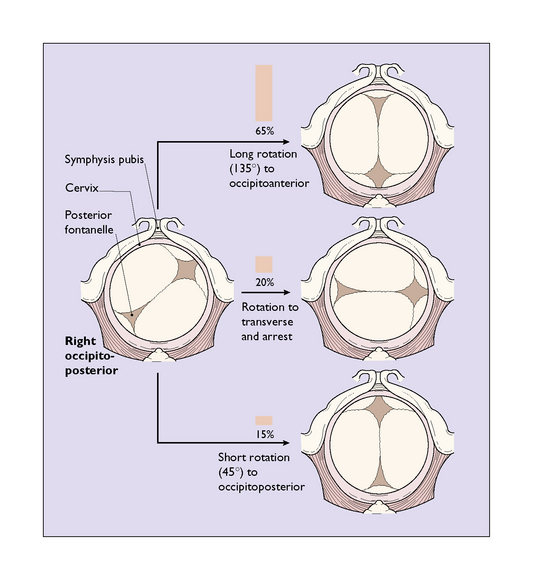

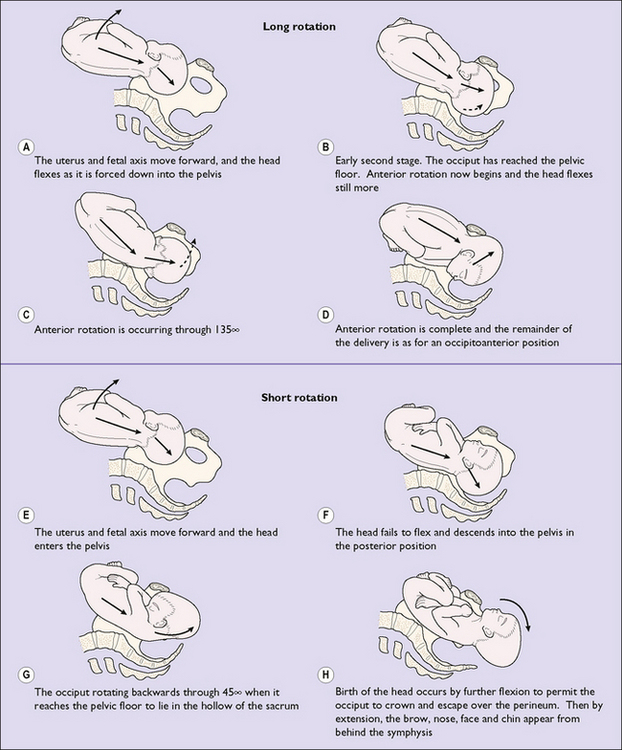

During labour the fetal head is forced deeper into the pelvis, and usually flexes on the fetal neck. Once full dilatation of the cervix has occurred its progress may be in one of three ways (Fig. 21.2):

Thus, in most cases the fetal head undergoes a long or a short rotation (Fig. 21.3).

Management of occipitoposterior presentations

There is no proven management that encourages rotation to an occipitoanterior position before labour starts. Once begun, the duration of labour tends to be longer in occipitoposterior positions and the mother requires more support, analgesia and hydration. Progress is monitored using a partogram. The descent of the head, and its position, are checked regularly. Any marked delay in the first stage of labour leads to prolonged labour (see p. 178–179) and a decision has to be made whether to continue or to perform a caesarean section. Delay in the second stage of labour of more than 1.5–2 hours’ duration indicates the need for help to deliver the baby. If the fetal head undergoes the long rotation a spontaneous vaginal delivery may be expected. This occurs in 65% of cases. If the fetal head undergoes the short rotation and descends to the pelvic floor in the posterior position, the infant may be born spontaneously (8% of all cases) or may need help by forceps or vacuum (7%). On the other hand, the fetus may not descend much beyond the ischial spines and a manual rotation and forceps delivery, Kjelland’s forceps delivery or vacuum extraction may be necessary (see Ch. 22). These procedures are also required if the fetal head arrests in a transverse diameter of the pelvis. Between 5 and 10% of babies who are occipitoposterior are delivered by caesarean section.

BREECH PRESENTATIONS

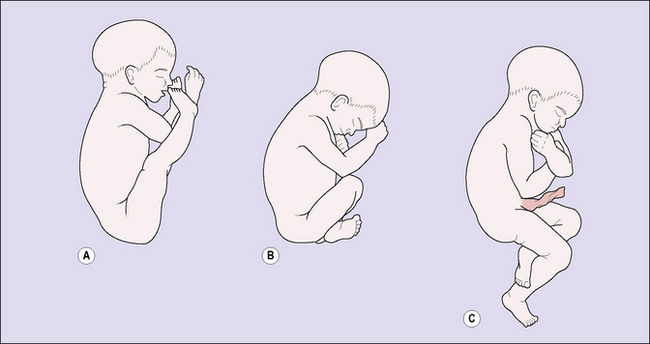

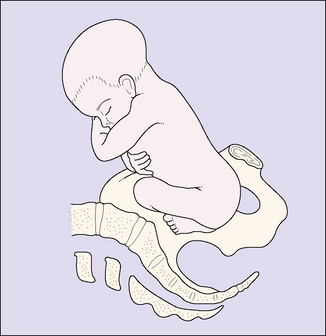

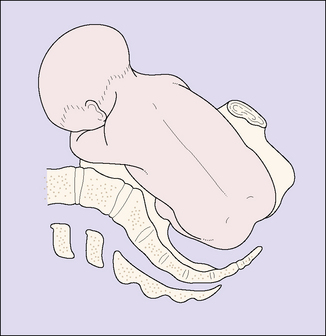

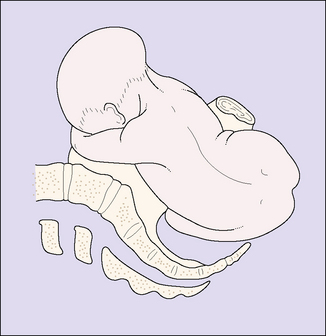

The frequency of breech presentation falls as pregnancy advances. At the 30th week of pregnancy 15% of fetuses present as a breech; by the 35th week the proportion has fallen to 6%, and by term only 3% present as a breech. Most of these babies spontaneously turn to become cephalic. If the presentation is still a breech at the 37th week many obstetricians attempt a cephalic version, which is described on pages 197–199. Version is easier if the fetus has flexed legs, one of the three types of breech presentation (Fig. 21.4).

Management of breech births

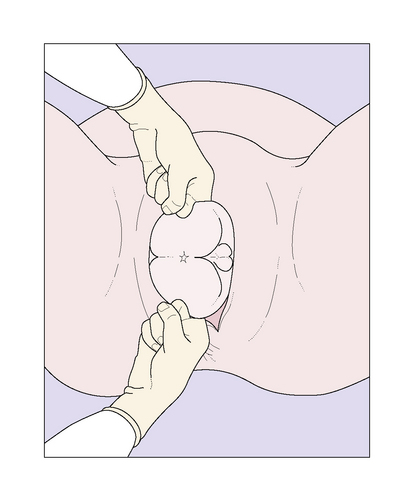

Vaginal breech birth

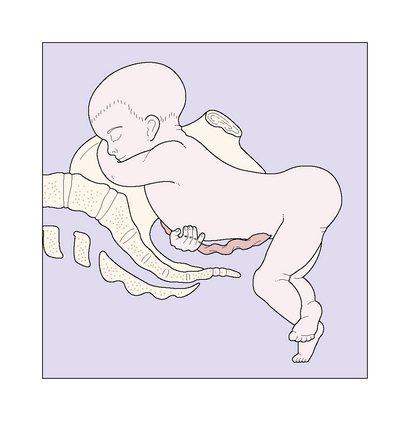

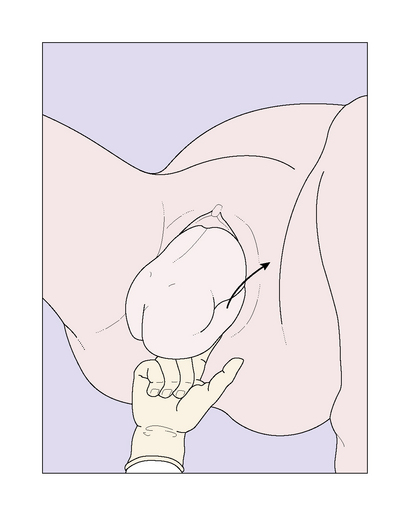

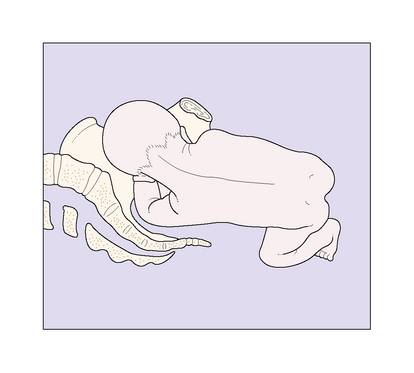

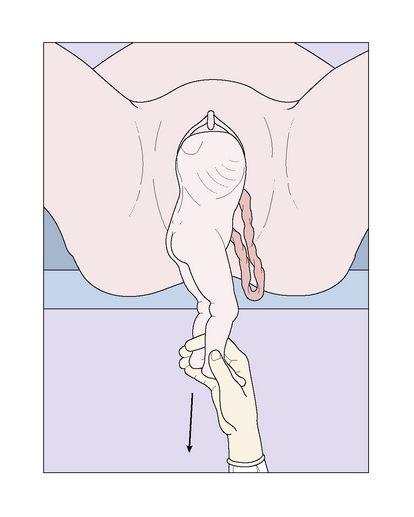

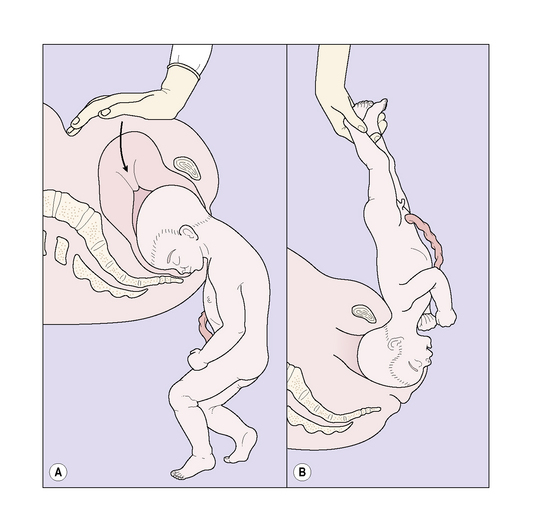

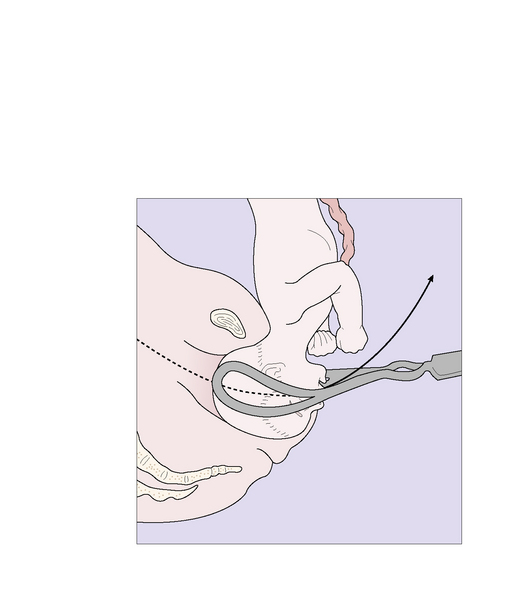

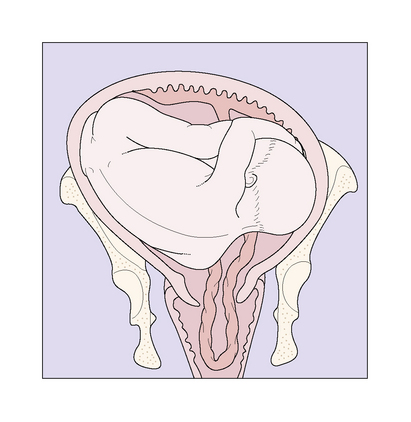

It is still important to understand the management and the mechanism of a breech birth, as an unexpected breech presentation may occur at full cervical dilatation with insufficient time to organize a caesarean section. This is shown in Figures 21.5–21.14 and is described in the captions.

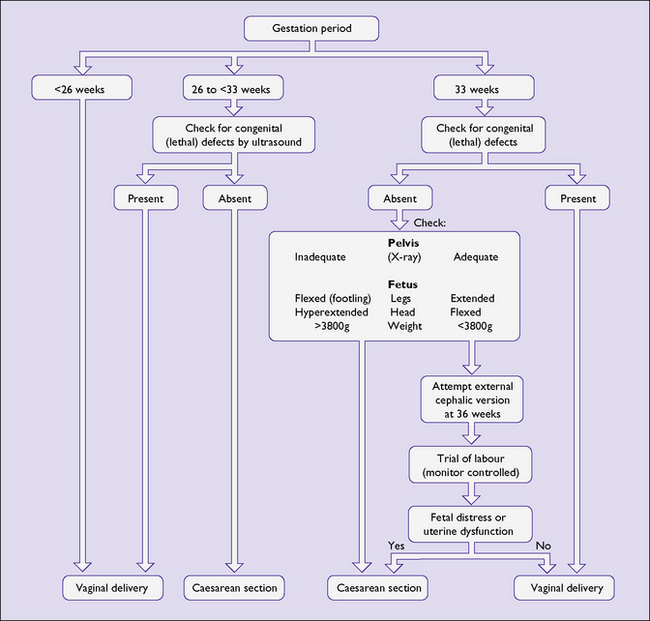

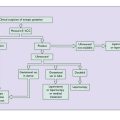

An algorithm for the management of breech presentations

Figure 21.15 presents an algorithm for the management of breech presentations. Not included is breech extraction, as in such cases the baby is delivered by the doctor. The main use of breech extraction is for the birth of a second twin, or if the breech is impacted in the midpelvic cavity. Unless the obstetrician is very skilled, caesarean section is safer.

TRANSVERSE LIES, OBLIQUE LIES AND SHOULDER PRESENTATIONS

Shoulder presentations, unstable lie, transverse lie and oblique lie may be detected in late pregnancy. These conditions occur in 1 in 200 births, usually in multiparous women. The aetiology is varied. They may occur in a lax multiparous uterus with no other complication of pregnancy, but may be associated with polyhydramnios, placenta praevia or a uterine malformation (see Fig. 36.4, p. 280). An ultrasound examination is helpful in excluding placenta praevia.

The diagnosis is made by finding a broad asymmetrical uterus with a firm, ballottable round head in one iliac fossa and a softer mass in the other (Fig. 21.16).

FACE PRESENTATIONS

Face presentation is rarely diagnosed before labour, and even then may be missed until a face with swollen, distorted lips appears at the vulva. Abdominal palpation may reveal a peculiar S-shaped fetus with feet on the opposite side to the prominent occiput. The fetal head has not usually entered the pelvis (Fig. 21.17).

Vaginal examination during labour may clarify the presentation (Fig. 21.18), but in late labour, when much facial oedema has occurred, a breech may be misdiagnosed.

Mechanism and management of labour

In most cases the face enters the transverse diameter of the pelvis with the fetal chin in a mentotransverse position. Descent into the pelvis is delayed until late in the first stage or the second stage of labour (Fig. 21.19). Rotation usually occurs anteriorly so that the chin lies behind the pubis, and delivery occurs spontaneously by flexion of the head or may be aided by forceps. In a few cases the fetal chin rotates posteriorly, impacting the fetal head and preventing vaginal delivery. The impacted fetal head may be rotated using Kjelland’s forceps or, preferably, the fetus may be delivered by caesarean section.

BROW PRESENTATIONS

Treatment consists of caesarean section, unless the baby is grossly abnormal or dead, when a destructive operation may be chosen (see p. 199).

MULTIPLE PREGNANCY

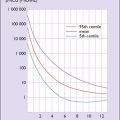

Because of the greater demands for nutrients, a fetus in a multiple pregnancy tends to be smaller than a singleton fetus, as its growth in utero is slower (Fig. 21.20).

Fig. 21.20 The intra-uterine growth of multiple and single pregnancies as assessed by ultrasound fetometry.

Management of multiple pregnancy

Compared with a singleton pregnancy, a multiple pregnancy is likely to be associated with more complications (Table 21.1). For this reason the expectant mother requires additional antenatal care. She should be seen at 2-weekly intervals from the time of diagnosis. Maternal anaemia should be sought and treated, and there is a strong argument for insisting that the patient takes folic acid 4 mg and an iron salt each day. When a woman carrying twins goes into preterm labour, the decision whether to deliver the twins by caesarean section or to attempt a vaginal birth has to be made. A problem is that in 20% of twin pregnancies the weight of one twin is 20% less than that of the other. There is no consensus about the safest method to use.

Table 21.1 Complications of pregnancy in singleton and multiple pregnancies

| Complication | Singleton (%) | Twin (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertensive disorders | 5 | 15 |

| Anaemia | 3–5 | 15 |

| Polyhydramnios | 2 | 12 |

| Intra-uterine growth restriction | 10 | 25–33 |

| Congenital anomalies | 2–4 | 4–8 |

| Preterm birth | 5 | 40 |

Management in labour

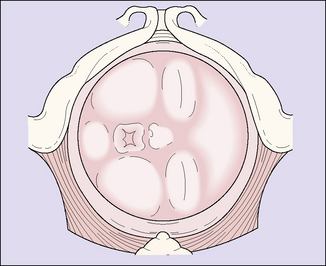

The position of the leading fetus should be checked on admission. In 45% of twin pregnancies both fetuses present as cephalic; in 25% as cephalic and breech; and as breech and cephalic or breech and breech in 10% each. If the first twin presents transversely, caesarean section is the preferable approach. If the first twin presents as a breech it is common practice (as yet unsupported by high-level evidence) to perform a caesarean section. In other cases a vaginal birth may be expected. The management of the labour is conducted in the way already described (Ch. 8). When the membranes rupture a vaginal examination is performed to check whether the umbilical cord has prolapsed.

Psychological effects of twins on the parents

In the postnatal period the demands of caring for two small babies adds to the problem of adjusting to parenthood (see p. 92–93), and usually means that the couple have little time to be with each other to enhance their general and their sexual relationship. In the period after childbirth, more women who have given birth to twins report anxiety and depression and often need support and help. Women report that discussion of these matters during pregnancy and the availability of support both during and after pregnancy reduce the stress of having twins. Fortunately, in the community there are self-help groups whose support and counselling are invaluable. However, the doctor or nurse attending the woman during and after pregnancy should be aware of the problems and of the need to talk with the woman and her partner.

PROLAPSE OF THE UMBILICAL CORD

Although prolapse of the umbilical cord is not itself a malpresentation, it is more likely to occur when there is a fetal malpresentation or position. For this reason it is included in this chapter. Prolapse of the umbilical cord occurs in 1 in 300 deliveries. The cord may be contained within the forewaters, when it is said to be presenting, or may have prolapsed to lie in front of the fetal presenting part after the membranes have ruptured (Fig. 21.21).