Ablation Techniques

The application of minimally invasive hysteroscopic techniques to surgically manage intractable uterine bleeding has been well documented as an efficacious and cost-effective alternative to hysterectomy.

The indication for the operation is abnormal uterine bleeding in a woman who wishes to preserve her uterus or in whom a hysterectomy would be judged too risky. The contraindications for surgery would include the presence of adenocarcinoma of the endometrium, atypical hyperplasia, nonreverting benign hyperplasia, dysmenorrhea, or concurrent adnexal mass.

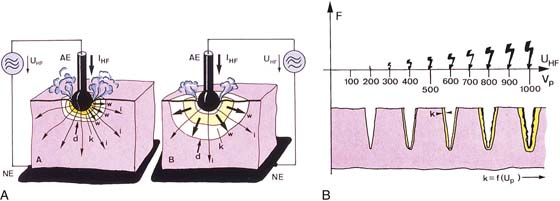

The term ablation has specific meaning. Ablation translates into vaporization of tissue, which is typically accomplished by thermal methods. When tissue cells are heated to 100°C, cell water is converted from a liquid to a gaseous state (steam). This change results in physical volume expansion within the intracellular space and a resultant explosive evaporation of the cell and its contents, that is, the cell virtually disappears. The most consistent and rapid vaporization is witnessed when the 100°C temperature is rapidly attained. For the aforementioned reasons, the best ablation procedures employ laser or radiofrequency (RF) electrosurgery techniques (Fig. 109–1A, B).

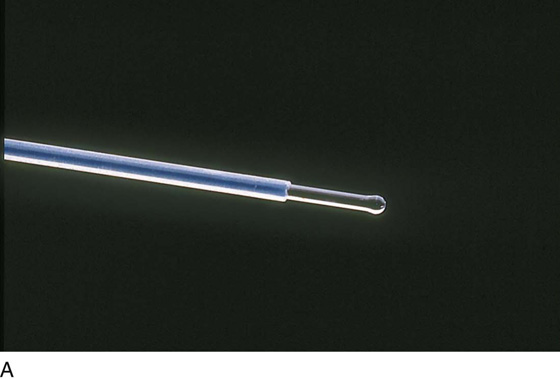

The laser used most commonly for endometrial ablation is the neodymium yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd-YAG) laser. This laser penetrates liquid media, exerts a supplementary coagulating action, is delivered by a 1-mm fiber via the operating channel of a hysteroscopic sheath, and passes through the endometrium to exert its principal action within the superficial myometrium (Fig. 109–2A through C).

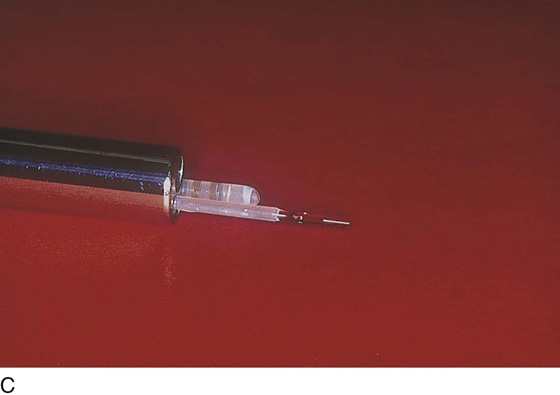

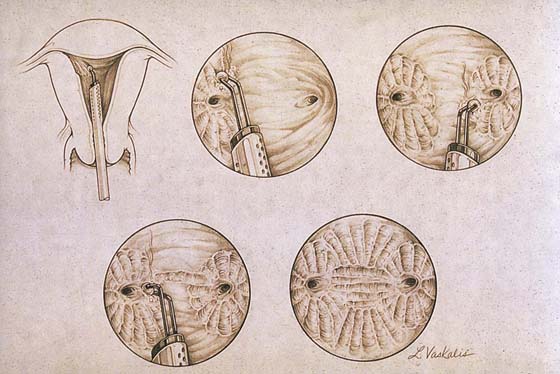

The electrosurgical device of choice is the ball electrode, which alternatively may be delivered to the operative site by a hysteroscopic operative sheath or by a specially constructed sheath designed with an “in-and-out” sliding mechanism. The electrode is a monopolar, double-armed ball, cylinder, or cutting loop (Fig. 109–3).

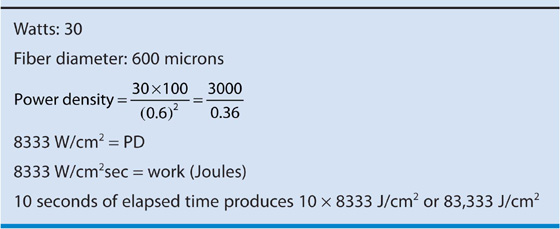

The final common path (i.e., tissue heating) is identical regardless of whether an Nd-YAG laser fiber or a monopolar electrode is used. The most important factor related to the efficiency of the ablation is the power density, that is, the power absorbed by a unit of tissue (W/cm2) or the energy density (J/cm2), or the product of power density and time in seconds (Table 109–1). For example, the energy density for laser action on tissue over a period of 10 seconds (referring to parameters shown in Table 109–1) would be 8333 × 10, or 83,333 J/cm2.

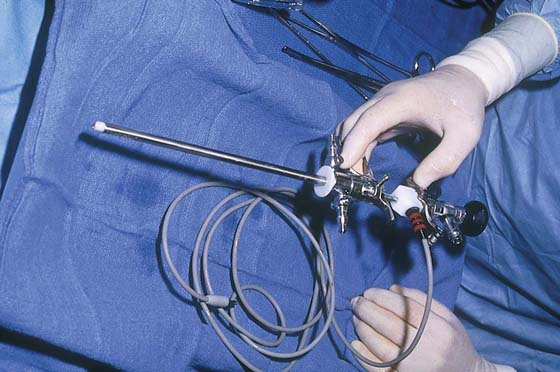

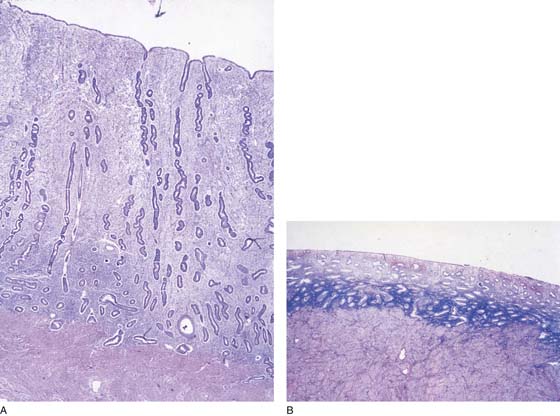

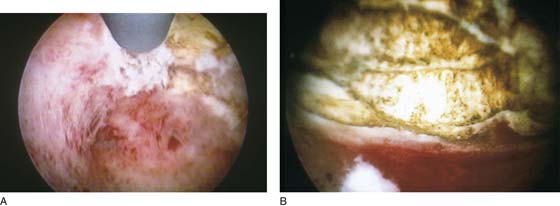

The technique for ablation utilizing an Nd-YAG laser begins with preparation of the endometrium 1 month before ablation by the administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (Lupron). The endometrium has been preoperatively sampled and has shown to be benign (Fig. 109–4A, B). The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, prepared, and draped. The cervix is dilated, and the operative hysteroscope, to which an endoscopic video camera has been attached, is inserted into the uterine cavity via the transcervical route with the medium intake channel wide open. In this instance, normal saline (0.9%) is the medium of choice (Fig. 109–5).

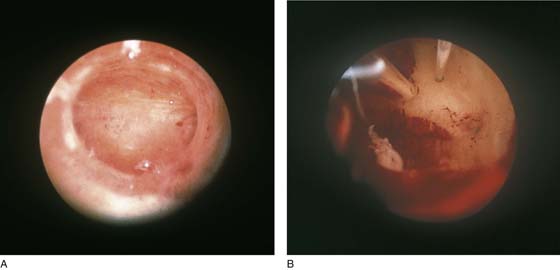

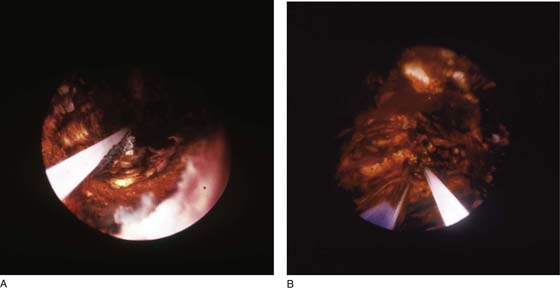

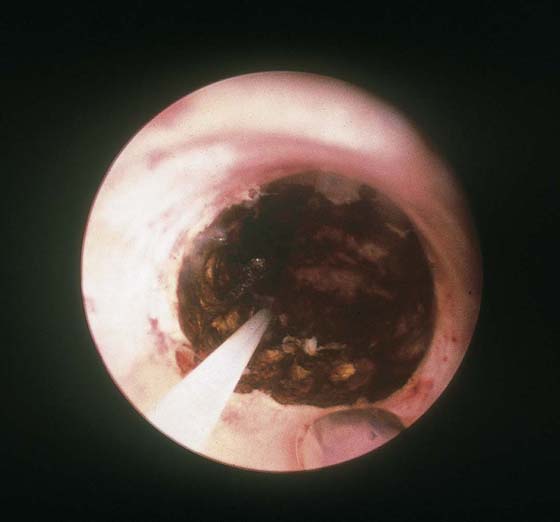

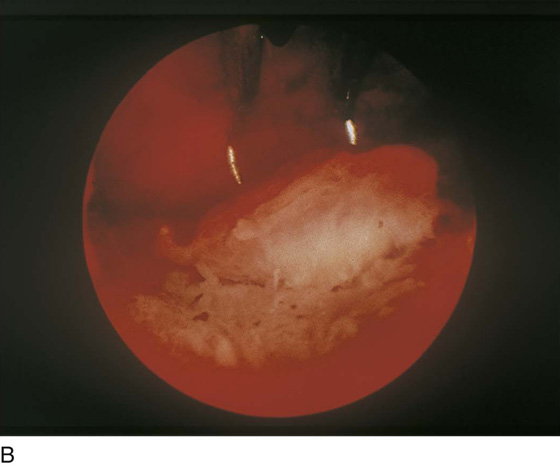

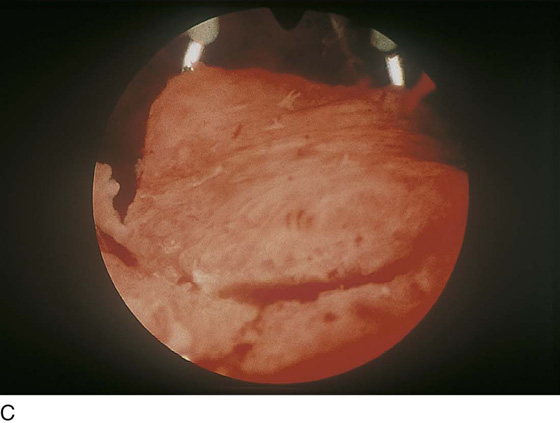

After inspection of the cavity, the 1200-µm laser fiber is inserted through the operating channel and makes light contact with the endometrium (Fig. 109–6A, B). Beginning on the anterior wall, ablation is initiated. The fiber is advanced under direct panoramic view. As the fiber is drawn toward the hysteroscope, power is effected by depressing the foot pedal of the laser. The operator views the field from the video screen (Fig. 109–7). Row upon row of endometrium is ablated as the laser fiber is dragged over it, analogous to mowing a lawn (Fig. 109–8A, B). After the anterior wall has been ablated, the fundus and the cornua are treated via a side-to-side motion. Finally, the posterior and lateral walls are destroyed (Fig. 109–9). The ablation is carried from the top of the uterus (fundus) to the level of the internal cervical os (Fig. 109–10). The cervix is not ablated. Upon completion of the operation, medium inflow is restricted and the outflow channel is shut off. These latter maneuvers decrease intrauterine pressure. The surgeon observes the cavity for any sign of bleeding. Finally, the instruments are completely removed.

FIGURE 109–1 A. The ball electrode on the left attains vaporization temperature more rapidly than the electrode on the right. On the right, lower temperatures (i.e., coagulating) produce a larger area of thermal conduction. B. Electrosurgical (RF) cutting occurs when vaporization temperatures are rapidly reached and the electrode produces high power densities. This may be demonstrated by the relative size of the spark. As greater voltages are reached, a corresponding high level of coagulation accompanies the vaporization. AE, active electrode; f, intensity of arcs; IHF, current concentrated at one point; K, depth of coagulation; NE, neutral electrode; UHF, voltage; Vp, peak voltage.

FIGURE 109–2 A. The tip of a 1000-µm, sculpted laser fiber (Nd-YAG) is shown. The bulbous tip is ideal for ablation of the endometrium. B. The fiber is being fed into one of two available operating channels of the hysteroscopic sheath. C. The sculpted point of a 1000-µm laser fiber protrudes from the end of the isolated hysteroscopic sheath. A suction cannula protrudes from a second operating channel.

FIGURE 109–3 Currently, most practitioners employ the resectoscope to ablate the endometrium. As illustrated, the advantage of this tool lies in easy manipulation of the sliding trigger operation.

FIGURE 109–4 A. The tall, vascularized, unprepped endometrium is in stark contrast to (B) the thin, inactive endometrium, which is produced by hormonal suppression.

FIGURE 109–5 A pump may be useful for delivering the distending medium to the uterine cavity because it propels the fluid at a constant rate.

FIGURE 109–6 A. A well-prepared thin endometrium is seen just before the operative equipment is inserted. B. The laser fiber is seen above at 12 o’clock. The suction cannula is located to the left of the laser fiber.

FIGURE 109–7 The operator performs hysteroscopic surgery via a video monitor. The assistant sees what the surgeon sees.

FIGURE 109–8 A. The ablation (with an Nd-YAG laser) is well under way. The cavity is 80% destroyed. B. The ablation is complete. The suction cannula is used to clean debris and blood from the field.

FIGURE 109–9 The hysteroscope views the field from the upper cervical canal.

FIGURE 109–10 The hysteroscope is withdrawn. Note: No ablation is done within the cervix.

TABLE 109–1  Energy Density for Laser Action on Tissue

Energy Density for Laser Action on Tissue

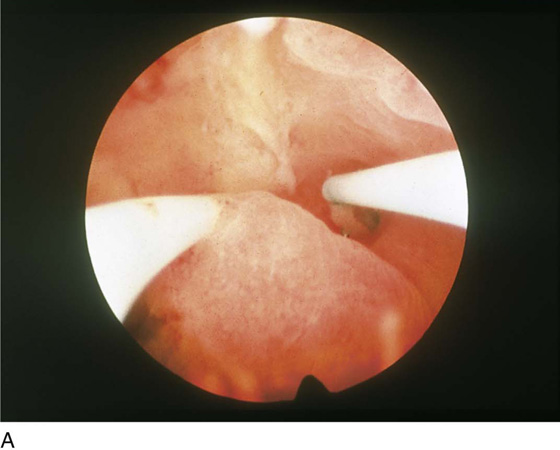

When the resectoscope and radiofrequency electrosurgically powered electrodes are employed, the general procedure is similar to that described for the Nd-YAG laser, except that the distending medium must be nonelectrolytic, that is, not saline (Fig. 109–11). The safest of these media is 5% mannitol, which is iso-osmolar and permits concentration of current density sufficient to effect ablation. As with the laser, a systematic plan is followed to accomplish a complete endometrial ablation. It is most convenient that the fundus and the cornua are treated first because the entire resectoscope (with the electrode extended) must be gingerly moved from side to side (from right to left or vice versa) (Fig. 109–12). Next, the anterior and finally posterior walls are ablated (Fig. 109–13A, B). The technique for anterior and posterior walls is to extend the electrode away from the objective lens of the hysteroscope, make contact with the endometrium, and apply power as the electrode makes its controlled return to the sheath (see Fig. 104–1).

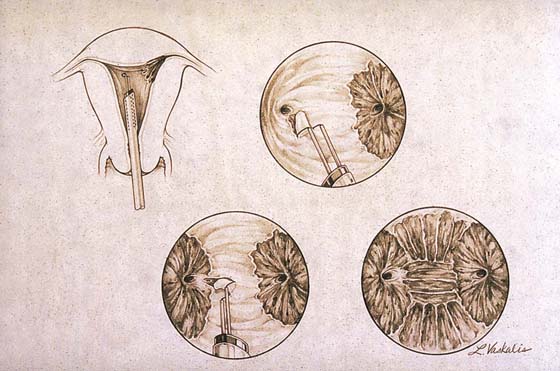

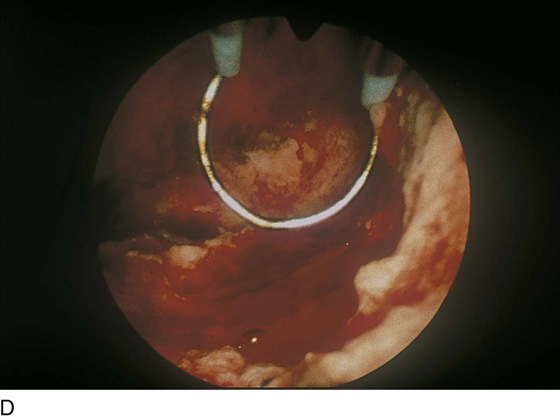

Endometrial resection has gained limited popularity in the United States; however, it is practiced widely in the United Kingdom and in Europe. In this case, a wire-loop electrode is substituted for the ball. Strips of endometrium are cut out and retrieved (Fig. 109–14). The procedure is otherwise identical to the previously described ablative technique. The risk with this operation involves resecting too deeply with resultant bleeding or perforation (Fig. 109–15A through C).

An exceedingly important part of any operative hysteroscopy is the accurate management of infused and returned medium. Fluid deficits or lack thereof must be determined continuously from the beginning to the end of the procedure. Immediately postoperatively, the patient is observed for bleeding and fluid overload. The author prefers to give a second injection of Lupron to discourage endometrial regeneration.

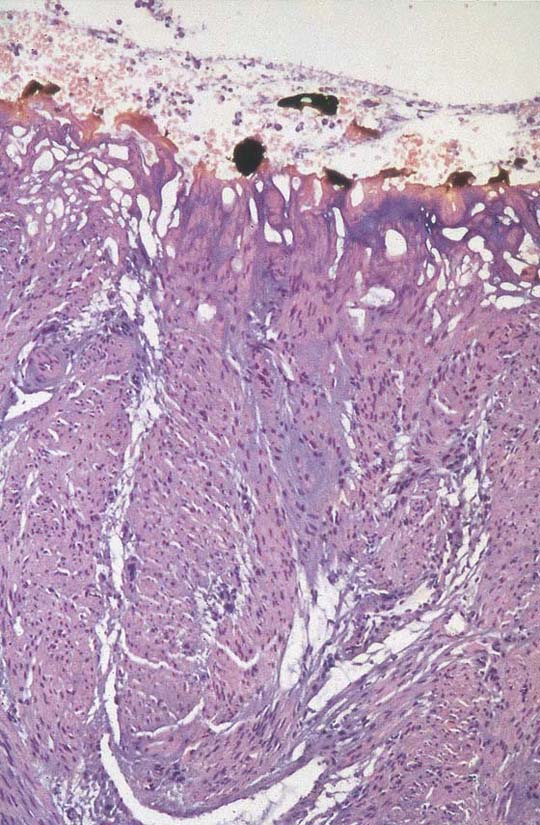

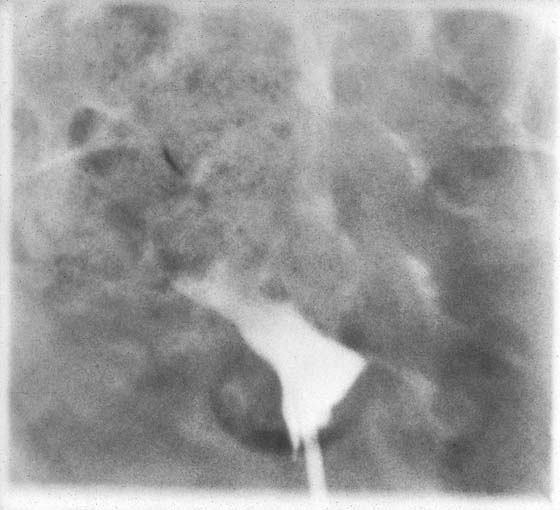

The final goal of endometrial ablation/resection is total destruction of the tissue lining the uterine cavity to the level of the inner aspect of the myometrium. Histologic sampling should be able to document the destruction (Fig. 109–16). A 4-month hysterogram should show a small, shrunken cavity with or without adhesions (Fig. 109–17).

FIGURE 109–11 The roller ball electrode is large and creates a low power density even at high power. Therefore, to ablate rather than coagulate, the time on tissue must be increased.

FIGURE 109–12 The technique for resectoscopic ablation is illustrated. The power is lowered for ablation of the cornua and fundus. It is increased for the anterior and posterior walls.

FIGURE 109–13 A. A ball electrode is shown in contact with the anterior uterine wall. The current has just been activated; the white area is coagulated; the yellow area (myometrium) has been ablated. B. The sharp demarcation between ablated tissue (anterior wall and upper half of the fundus) and intact endometrium is shown here.

FIGURE 109–14 This drawing shows an endometrial resection performed with the cutting loop electrode of the resectoscope.

FIGURE 109–15 A. The double-armed loop electrode has been extended away from the objective lens of the hysteroscope. B. As the electrode returns toward the sheath, the electric current is activated and the loop cuts through the endometrium. C. Close-up of a piece of endometrium shaved by the loop electrode. D. The tissue has been sliced away.

FIGURE 109–16 Charred and thermally damaged endometrium after hysteroscopic ablation.

FIGURE 109–17 Four-month postoperative hysterogram reveals a shrunken, deformed uterine cavity.