Chapter 20 Abdominoplasty

Summary

Introduction

The modern history of abdominal contouring began in 1899 with Kelly1,2 performing an abdominal apronectomy or dermolipectomy to eliminate a large abdominal pannus. In 1957, Vernon3 described umbilicus transposition. Gonzalez-Ulloa4 in 1959 popularized the abdominoplasty technique describe by Somalo5 in 1946 where he resected a circular skin pattern from the lower abdominal region extending around the waist in a belt lipectomy fashion. In 1967, Pitanguy6 presented his technique consisting of inconspicuous scars in the lower abdomen and groin, wide superior dissection up to the costal margins and xiphoid, plication of the transverse abdominal rectus muscle and umbilicoplasty. Regnault,7 in 1972, introduced the concept of abdominoplasty in a ‘W’ pattern, and in subsequent years described modifications of the technique including a fleur-de-lis and modified belt lipectomy. Grazer,8 in 1973, reported 44 cases of abdominoplasty hiding the incision in the bikini line. The concept of miniabdominoplasty was introduced by Elbaz and Flageul9 in 1971, and later modified by Glicenstein10 in 1975. The introduction of liposuction in the late 70s added a significant tool to abdominoplasty and body contouring in general.11 Matarasso,12,13 in the late 80s, made a significant contribution by introducing his classification scheme and by describing the incorporation of liposuction with modified abdominoplasty procedures. Lockwood,14 in 1991, described a new concept – the superficial fascial system (SFS), which is a highly organized collagen structure responsible for anchoring the skin of the body and for supporting the weight of the fat throughout life. In 1995 he introduced a high lateral tension abdominoplasty (HLTA), which was designed to create more lateral abdominal improvement and anterior thigh elevation.15 Within the past decade Saldanha16 introduced and popularized ‘lipoabdominoplasty’, which has become fairly popular in South America and Europe. It is a technique that utilizes extensive liposuction of the entire abdomen combined with minimal undermining in the hope of reducing the risks of tissue necrosis and seroma formation.

Indications

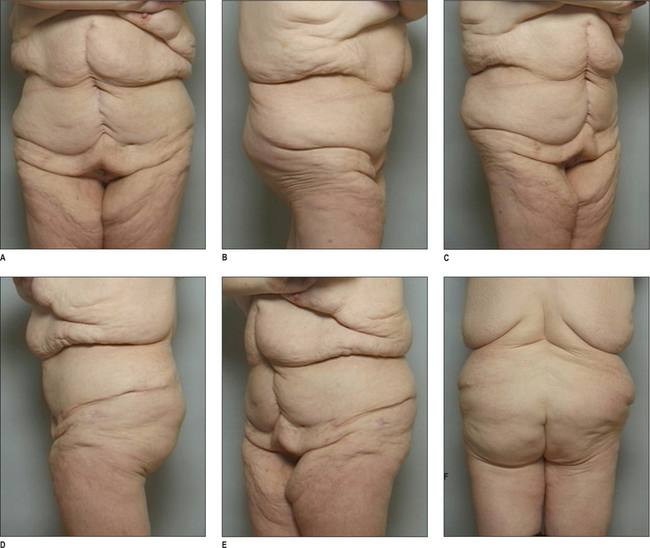

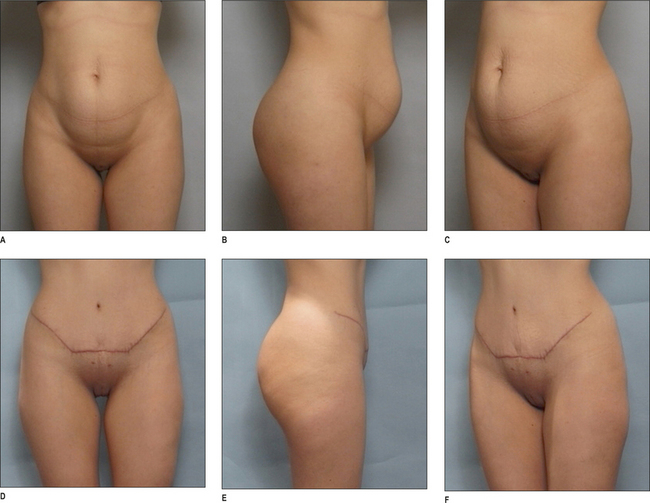

Patients seeking abdominoplasty most often complain of excess skin and subcutaneous tissue in the abdomen and abdominal protrusion due to laxity of abdominal wall caused by previous pregnancy, weight fluctuations and/or aging. Many of these patients will present with lipodystrophy of the hips and lateral thighs as well.17 A traditional abdominoplasty is indicated when the deformities involve both the supra and infraumbilical regions whereas a mini-abdominoplasty is usually indicated if the problems are limited to the infraumbilical region. Although most patients are female, males do present with similar problems, but often complain of adiposity in the flank areas and supraumbilical rectus diastasis.18–20

Smoking has been implicated in occlusive microvascular thrombosis and delayed wound healing and when associated with a procedure that already compromises the blood supply of the abdominal skin flap, can result in tissue necrosis and jeopardize the outcome. Active smokers are excluded by most surgeons, but some surgeons are willing to operate on them utilizing techniques that reduce abdominal flap elevation to reduce the risk of vascular compromise.21–23

Previous abdominal scars

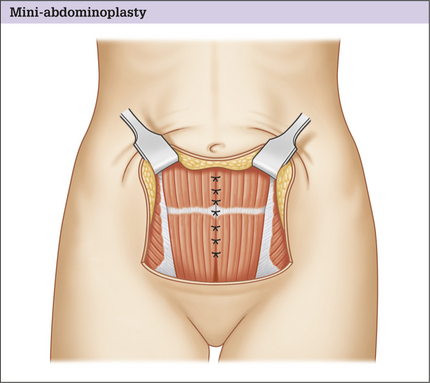

Mini-abdominoplasty

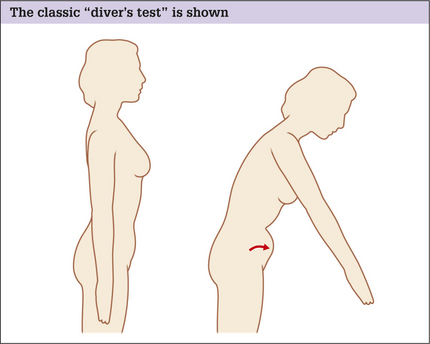

Indications for mini-abdominoplasty are limited to patients who present with abdominal laxity restricted to the infraumbilical region.24 The laxity has to be minimal and may be of the abdominal wall and/ or of the skin/fat envelope. Physical examination of the abdomen in the supine position will demonstrate infraumbilical rectus diastasis, which can be confirmed by the ‘diver’s test’ (see Fig. 20.1). These patients are usually young women who have had one or two pregnancies, have good skin elasticity, and are not overweight. Mini-abdominoplasty, with any of its modifications, is not a procedure that is often employed because it is the unusual patient that will fit its required criteria.

High lateral tension abdominoplasty

An HLTA15,25 is fundamentally different from the traditional abdominoplasty in the following ways:

Lipoabdominoplasty

Lipoabdominoplasty was introduced and popularized by Saldanha16 from Brazil. This technique, with a variety of its forms, is becoming more popular around the world especially in South America and Europe. For the surgeons who espouse lipoabdominoplasty, it is an alternative technique that accomplishes many of the same goals as traditional abdominoplasty but maybe safer and associated with less complications (Box 20.1). Currently many American plastic surgeons are starting to utilize the technique in its entirety or at least in some of its main aspects. Lipoabdominoplasty has some similarities to HLTA.

Box 20.1 Theoretical advantages of lipoabdominoplasty

Preoperative Considerations

Physical examination

Skin

The overall quality of skin, including scars and stretch marks should be noted. The skin should be examined to determine its vertical excess and the extent of its laxity in the different regions of the abdomen. Often multiparous women present with stretch marks that involve the infra and supraumbilical regions.26 The patient needs to understand that infraumbilical skin will most often be removed, but supraumbilical stretch marks will not. These remaining stretch marks are often less unattractive when stretched by the procedure and can be hidden by some bikini patterns because of their transference to the lower abdomen.

Subcutaneous fat

A protruding abdomen may be caused by a number of factors, alone or in combination.

Abdominal wall laxity

A third reason for a protruding abdomen is abdominal wall laxity. It is essential to ascertain the integrity of the abdominal wall, whether there are any hernias present, and the extent of intra-abdominal or visceral fat. The exam is fairly easy in thin patients, but can be more cumbersome and difficult in the overweight or obese patient.

A number of tests can be performed, which alone or in combination, can give the examiner a feel for the degree and extent of any laxity. Initially the patient is asked to stand and relax their abdominal wall completely. For many this is not easy and they must be coaxed into cooperating. An appreciable amount of abdominal protrusion in this position usually indicates significant abdominal wall laxity. To confirm the result of this simple test, the patient is asked to perform the classic ‘diver’s test’ (Fig. 20.1).

Operative Approach

Relevant anatomy

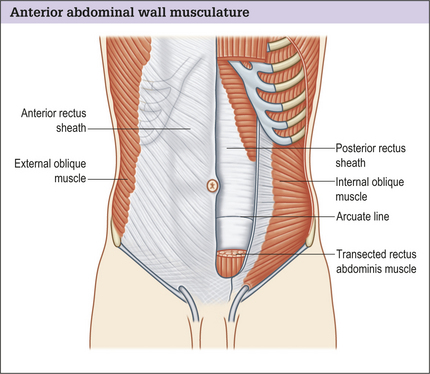

The anterior abdominal muscle wall may be considered to have two parts:

The rectus muscle is enclosed in a stout sheath formed by a bilaminar aponeurosis, which passes anteriorly and posteriorly around the muscle, decussating in the midline to form the linea alba. Anteriorly the sheath is made up of the external oblique fascia and the anterior portion of internal oblique fascia. Posteriorly the sheath is made of the posterior portion of the internal oblique fascia and the transversus abdominis muscle fascia. Halfway between the umbilicus and the pubis, the posterior sheath layers pass anteriorly at the arcuate line of Douglas. The lack of support below the line of Douglas leads to a natural tendency toward lower abdominal fullness.

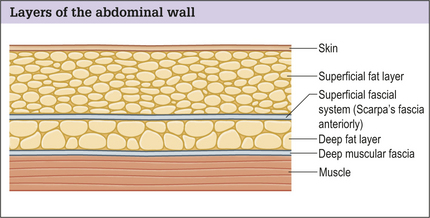

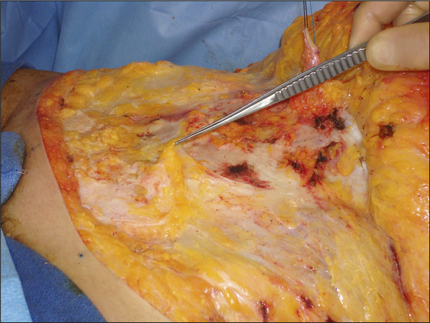

Subcutaneous abdominal fat is compartmentalized into superficial and deep layers divided by the superficial fascial system, which in this region of the body is called Scarpa’s fascia. In patients who are relatively thin, the two layers of fat are fairly close to each other in thickness. In patients who have a large BMI the superficial fat layer is often much thicker than the deep layer (Fig. 20.3). The superficial fat layer is compact, dense with fat cells contained within well organized fibrous septa, whereas the deep fat is a loose areolar layer.

Vascular zones

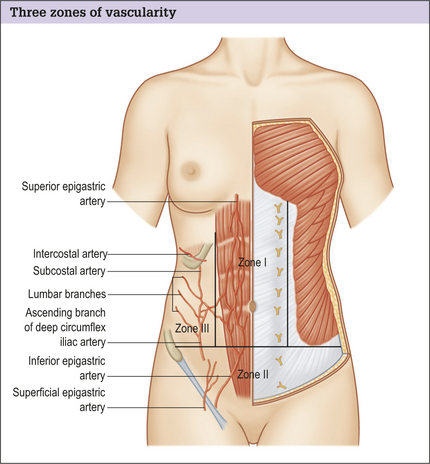

Regardless of the technique used when performing abdominoplasty, vascular territories are interrupted and should be taken into account especially when upper abdominal scars are present.27 Thus a thorough knowledge of the blood supply of the abdominal skin and fat is essential. Huger28 studied the blood supply to the abdomen and designated three vascular zones (Fig. 20.4):

Sensory innervation

Iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves supply sensory innervation to the groin and symphysis pubis, proximal portions of the scrotum and labia, and small adjacent area on the inner aspect of the thigh. These nerves can be entrapped during plication of the anterior rectus sheath in the lower abdomen.29,30

Fascial attachments

The lower trunk has fascial attachments between the skin and underlying muscle fascia that act as anchoring points or zones of adherence31 (Fig. 20.5), which tether the overlying skin to the underlying musculoskeletal anatomy, not allowing either descent or elevation with aging, weight fluctuation, or surgical manipulation.

Operative techniques

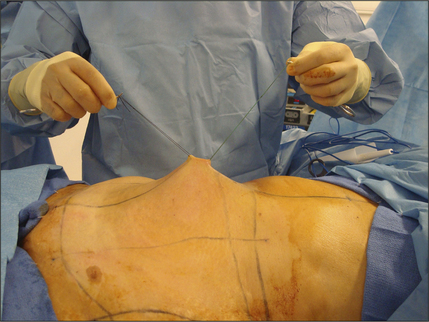

Markings

To eliminate dog-ears three general approaches, individually or in combination, can be utilized.

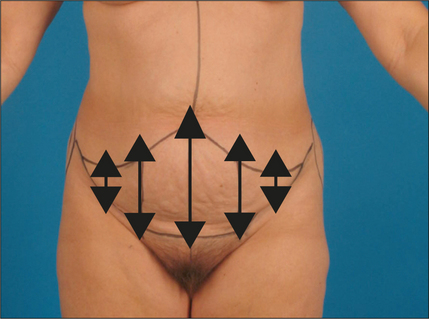

It is obviously important to control final scar position in abdominoplasty, and it is therefore helpful to think of an abdominoplasty closure in the same way as the closure of any elliptical defect. The greatest tension and tissue distortion occurs centrally, with minimal to no tension or distortion laterally (Fig. 20.6).

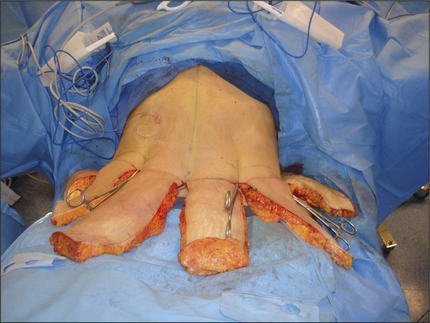

Abdominoplasty

Fig. 20.7 Traction sutures. These put traction on the umbilicus to facilitate the circumumbilical incision.

Fig. 20.12 Abdominal flap after being advanced. The amount to be resected is determined at key points.

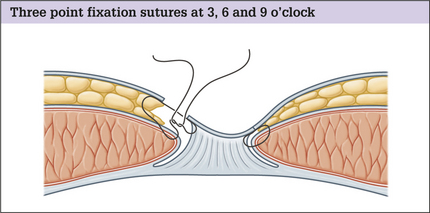

Our preferred method of umbilicoplasty

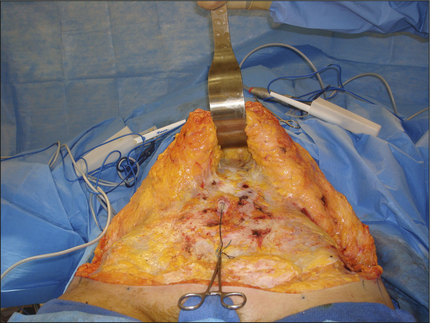

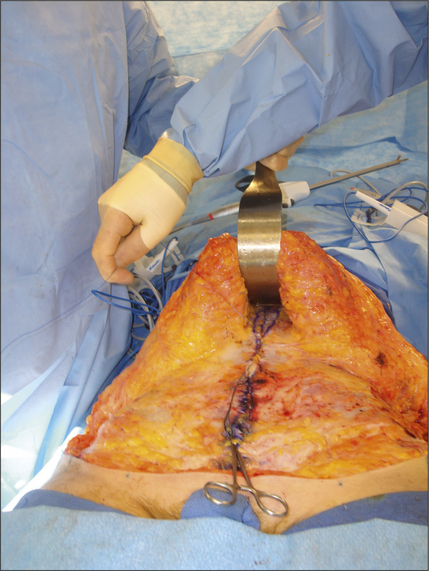

Closure of the abdominal wound

Mini-abdominoplasty

Fig. 20.14 Mini-abdominoplasty. The extent of flap dissection and abdominal wall plication is shown.

Modifications

High lateral tension abdominoplasty

Lipoabdominoplasty

Optimizing outcomes

Complications

Abdominoplasty is an extensive operation with potential risks and complications that need to be considered by both the patient and plastic surgeon.21,32–38 Abdominoplasty, alone or in combination with other procedures, carries the highest risk among body contouring procedures. As a general rule complications are more common in higher BMI patients and because many patients that present for abdominoplasty may be in the overweight-to-obese range, they need to be approached with caution and full disclosure.

Seroma

Most surgeons believe that closed suction drainage is the best way to prevent seromas from occurring, along with compression. Surgeons who utilize lipoabdominoplasty techniques consider that the etiology of seromas is related to creating a very large dissection pocket and the elimination of lymphatics, especially of the femoral region. Thus this technique tries to minimize both problems in the hope of reducing seroma occurrence. Other surgeons feel that it is the lack of adherence of the abdominal flap to the underlying abdominal wall that is responsible for seroma formation and advocate eliminating as much dead space as possible with mattress sutures.

Tissue necrosis

As discussed on p. 5, the blood supply of the abdominal flap skin and fat is reduced to varying degrees depending on the particular technique utilized and whether the patient has any concomitant risk factors such as a history of smoking or diabetes. Based on the pattern of the blood supply, the area most likely to necrose is located in a triangle of the abdominal flap that has its apex at the umbilicus and its base along the scar on either side of the midline, especially if there is T-shaped closure. To help reduce the risk of tissue necrosis it is wise to avoid operating on high-risk patients such as diabetics and smokers if possible, though not all surgeons steer clear of them. As a general rule, it is wise to perform as little elevation of the abdominal flap as possible that will create the desired contour, no matter which technique is utilized.

Contour irregularity

Contour irregularity is not an uncommon complication after abdominoplasty.

Box 20.2 Inverted ‘T’ or fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty

Some plastic surgeons prefer to utilize inverted ‘T’ or fleur-de-lis39-pattern procedures in patients that present with circumferential lower truncal excess, especially if the patient presents with a midline abdominal scar. We have almost abandoned this pattern as a primary procedure, especially since circumferential dermatolipectomy procedures have become main stream in plastic surgery as a reaction to the frequent presentation of the massive-weight-loss patient. The theoretical advantage of utilizing this technique is that it can eliminate horizontal as well as vertical excess and create waist narrowing by pulling the lateral tissues centrally. It is important to note that to safely utilize this technique it must not be thought of as a traditional abdominoplasty with a simple addition of a vertical wedge.

Disadvantages

Other disadvantages of a T-type resection are:

The position of the mons pubis can be altered for better or worse after abdominoplasty. If the mons is ptotic prior to surgery, it should be lifted, which is easy to accomplish because of the tension created by the resection of an abdominoplasty. It is more difficult, however, to keep the mons pubis from ending up too high, especially in patients who have a highly positioned umbilicus. To avoid this problem it best to place the mons pubis where it is felt to be most ideal and then tailor the abdominal flap based on that position. This may necessitate leaving the umbilical defect behind as a vertical scar either as part of a midline T-shaped closure or a vertical scar between the neoumbilicus and the mons. If such scars are contemplated, it is imperative that the patient is warned about the possibility prior to surgery with an explanation of why this may be necessary. To further hold the position of the mons in its ideal position, its underlying Scarpa’s fascia can be sutured to the underlying muscle fascia to prevent superior migration.

Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolus

Postoperative Care

Conclusion

Patients best suited for abdominoplasty surgery present with lower truncal excess limited to the anterior abdomen. Those with a high BMI greater than or equal to 30 have a greater complication rate. The technique used in any particular patient should be individualized to accommodate the patient’s anatomy and desires, but the extent of flap should be minimal to reduce vascular compromise. Complications are minimized by use of sequential compression devices, early ambulation, vigorous pulmonary toilet, appropriate hydration, discontinuing nicotine, birth control pills, and hormone replacement therapy, and avoiding lengthy operations.

1. Kelly H.A. John Hopkins Med J. 1899;10:197. Report of gynecological cases

2. Kelly H.A. Excision of the fat of the abdominal wall – lipectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910;10:229.

3. Vernon S. Umbilical transplantation upward and abdominal contouring in lipectomy. Am J Surg. 1957;94:490.

4. Gonzalez-Ulloa M. Belt lipectomy. Br J Plast Surg. 1967;13:179.

5. Somalo M. Cruciform ventral dermal lipectomy swallow-shaped incision. Prensa Med Argent. 1946;33:75.

6. Pitanguy I. Abdominal lipectomy: an approach to it through an analysis of 300 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40:384.

7. Regnault P. The history of abdominal dermolipectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1978;2:113.

8. Grazer F.M. Abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51:617.

9. Elbaz J.S., Flageul G. Chirurigie plastic de l’abdomen. Paris: Masson, 1971.

10. Glicenstein J. Difficulties of surgical treatment of abdominal dermodystrophies. Ann Chir Plast. 1975;20:147.

11. Illouz Y.G. Body contouring by lipolysis: a 5 year experience with over 3000 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:591.

12. Matarasso A. Abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16:289.

13. Matarasso A. Abdominolipoplasty: a system of classification and treatment for combined abdominoplasty and suction-assisted lipectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1991;15:111.

14. Lockwood T. Superficial fascial system (SFS) of the trunk and extremities: a new concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1009.

15. Lockwood T. High-lateral tension abdominoplasty with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:603.

16. Saldanha O.R., De Souza Pinto E.B., Mattos W.N.Jr, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty with selective and safe undermining.. 2003;27:322.

17. Aly A.S. Approach to the massive weight loss patient. In: Aly A.S., editor. Body contouring after massive weight loss. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006:49.

18. Borkan G.A., Norris A.H. Fat redistribution and the changing body dimensions of the adult male. Hum Biol. 1977;49:495.

19. Bouchard C., Bray G.A., Hubbard V.S. Basic and clinical aspects of regional fat distributions. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:946.

20. Fried S.K., Kral J.G. Sex differences in regional distribution of fat cell size and lipoprotein lipase activity in morbidly obese patients. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1987;11:129.

21. Grazer F.M., Goldwyn R.M. Abdominoplasty assessed by survey, with emphasis on complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:513.

22. Forrest C.K., Pang C.Y., Lindsay W.K. Detrimental effect of nicotine on skin flap viability and blood flow in randon skin flap operations on rats and pigs. Surg Forum. 1985;36:611.

23. Krueger J.K., Rohrich R.J. Clearing the smoke: the scientific rationale for tobacco abstention with plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1063.

24. Greminger R.F. The mini-abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:356.

25. Lockwood T. Maximizing aesthetics in lateral-tension abdominoplasty and body lifts. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31:523.

26. Elling S.V., Powell F.C. Physiological changes in the skin during pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:35.

27. Boyd J.B., Taylor G.I., Corbett R. The vascular territories of the superior epigastric and deep inferior epigastric systems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:1.

28. Huger W.E.Jr. The anatomic rationale for abdominal lipectomy. Am J Surg. 1979;45:612.

29. Choi P.D., Nath R., Mackinnon S.E. Iatrogenic injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in the groin: a case report, diagnosis, and management. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:1.

30. Liszka T.G., Dellon A.L., Manson P.N. Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment following abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:181.

31. Aly A.S. Options in lower truncal surgery. In: Aly A.S., editor. Body contouring after massive weight loss. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006:59.

32. Teimourian B., Rogers WBIII. A national survey of complications associated with suction lipectomy: a comparative study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:628.

33. Laub D.R.Jr, Laub D.R. Fat embolism syndrome after liposuction: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:48.

34. Hunter G.R., Carpo R.O., Broadbent T.R., Woolf R.M. Pulmonary complications following abdominal lipectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:809.

35. Davison S.P., Venturi M.L., Attinger C.E., Baker S.B., Spear S.L. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the plastic surgery patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;43e:114.

36. Matarasso A., Swift R.W., Rankin M. Abdominoplasty and abdominal contour surgery: a national plastic surgery survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1797.

37. Van Uchelen J.H., Werker P.M.N., Kon M. Complications of abdominoplasty in 86 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1869.

38. Kim J., Stevenson T.R. Abdominoplasty, liposuction of the flanks and obesity: analysing risk factors for seroma formation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:773.

39. Dellon A.L. Fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1985;9:27.