Abdominoperineal Resection

Principles of Preoperative Evaluation

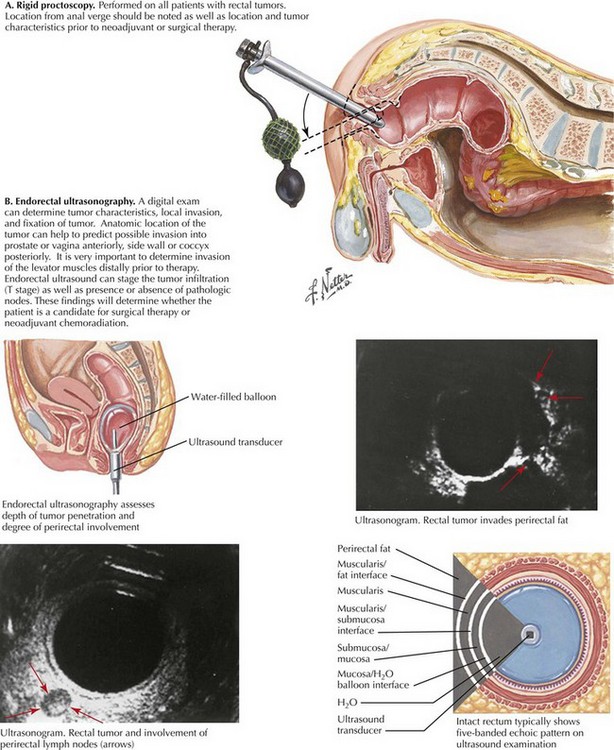

The patient is screened with a full colonoscopy. Digital rectal examination and proctoscopy are performed to confirm tumor location and to assess feasibility of a sphincter-sparing approach (Fig. 25-1, A). Digital vaginal examination and vaginoscopy are performed with the proctoscope to assess for local invasion. CT scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is done to survey for metastatic disease. Endorectal ultrasound is used for staging to assess the need for preoperative chemoradiation (Fig. 25-1, B).

Anatomic Approach to Left Colon Mobilization

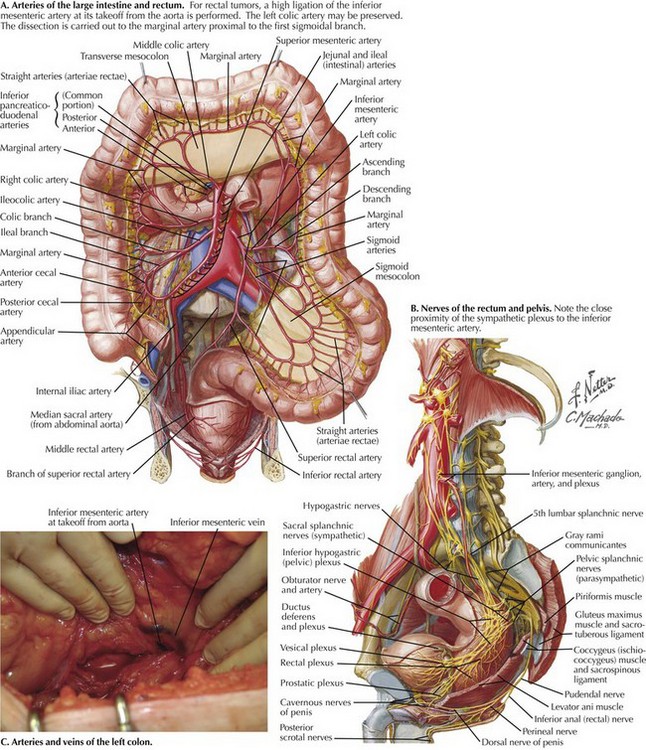

The mobilization is extended to the root of the mesentery, and the inferior mesenteric artery is identified at its takeoff from the aorta (Fig. 25-2, A). Branches of the sympathetic nerves, which lie deep to the IMA, are protected by keeping close to the fascia of the mesocolon as it wraps around the IMA, if necessary sweeping nerve branches dorsally and away from the vessel (Fig. 25-2, B). The IMA is isolated, clamped, and ligated. The left colic artery and the inferior mesenteric vein are divided and ligated at the level of the IMA (Fig. 25-2, C). The mesentery is divided perpendicularly to the level of the marginal artery, just proximal to the 1st sigmoidal branch. Unlike in low anterior resection, where extra length is needed for a tension-free colorectal anastomosis, mobilization of the splenic flexure is not required unless the patient is morbidly obese and extra length is needed for stoma construction.

Approach for Rectal Dissection

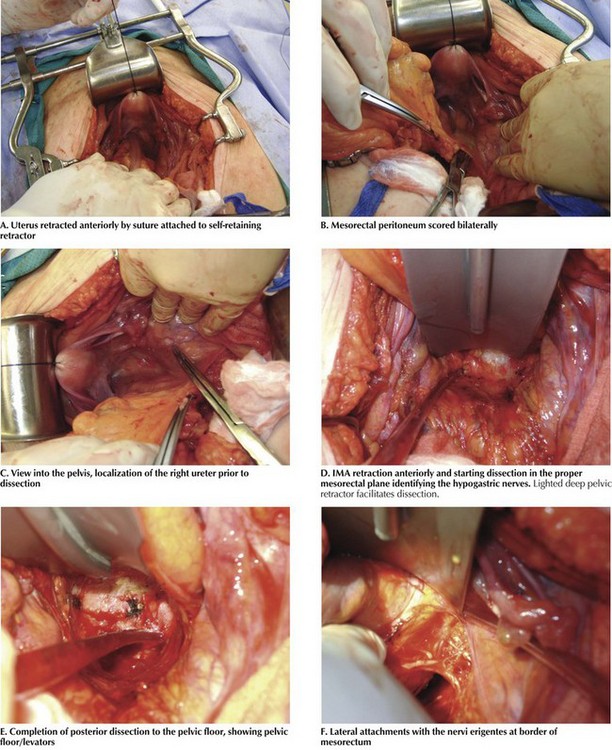

The patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position and a self-retaining retractor is inserted. It is helpful to place a figure-of-eight absorbable suture in the uterine fundus, retracting it anteriorly, and securing the suture to the self-retaining retractor (Fig. 25-3, A). In open surgical cases, the dissection is greatly facilitated by the use of lighted, deep pelvic retractors.

Mobilization of the rectum and its investing mesorectum and fascia begins behind the inferior mesenteric vessels, in the loose areolar tissue between the mesorectal fascia and the presacral fascia. The lateral peritoneum overlying the mesorectum is then scored (Fig. 25-3, B). Unless an extended resection is being performed, the ureters are generally easily protected because they lie deep to the fascia of the retroperitoneum. Nevertheless, the ureters’ location is verified throughout the dissection (Fig. 25-3, C). The right and left hypogastric nerves are identified and swept posteriorly and are carefully avoided. The dissection continues posteriorly to the pelvic floor with the use of electrocautery (Fig. 25-3, D).

Dissection of the pelvis proceeds posteriorly, then laterally, and finally anteriorly. By lifting the rectosigmoid junction anterior and cephalad and indenting the mesentery, this avascular plane can be identified and entered, anterior to the nerves. If in the proper plane, cautery is adequate for hemostasis. Posteriorly, the dissection is continued through the filmy, avascular plane until the dissection reaches the rectosacral (Waldeyer’s) fascia. While the dissection proceeds posteriorly, its direction will tilt more anteriorly, above the level of the coccyx (Fig. 25-3, E).

Laterally, the presacral parasympathetic nerves (nervi erigentes) can be seen along the pelvic side wall at approximately the level of the lateral stalks and middle rectal arteries (Fig. 25-3, F). The mesorectum is retracted medially and the dissection is continued on the right and left, and the nervi erigentes are allowed to fall laterally as the dissection ensues. This procedure is continued until the pelvic floor and levator muscles are reached.

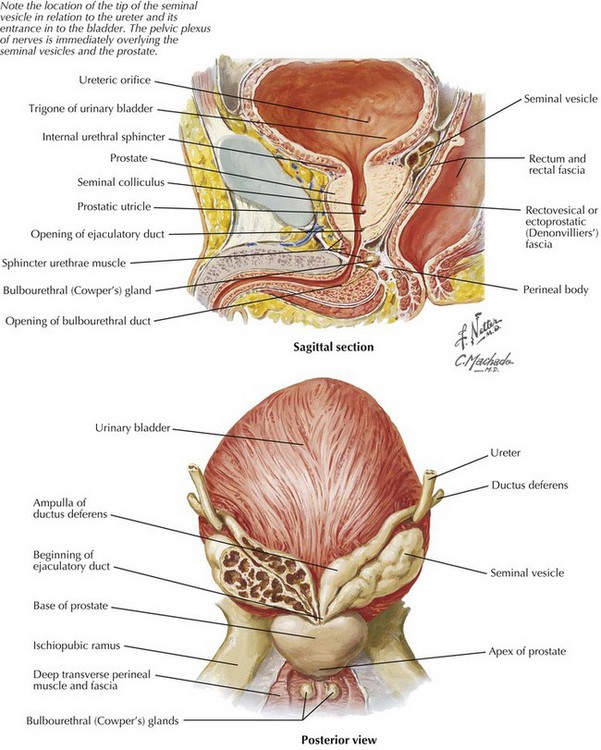

The anterior dissection is now begun. The peritoneum in the cul-de-sac is scored just anterior to the fold at the peritoneal reflection. Denonvilliers’ fascia is reflected posteriorly to keep the mesorectum intact on the specimen. The surgeon must keep in mind the location of the pelvic plexus of nerves that overlies the seminal vesicles anteriorly in the male. It is important to avoid skeletonizing the vesicles to prevent nerve injury. Also to avoid injury, the proximity of the ureters to the apex of the seminal vesicles must be considered (Fig. 25-4). The anterior dissection is continued to the pelvic floor.

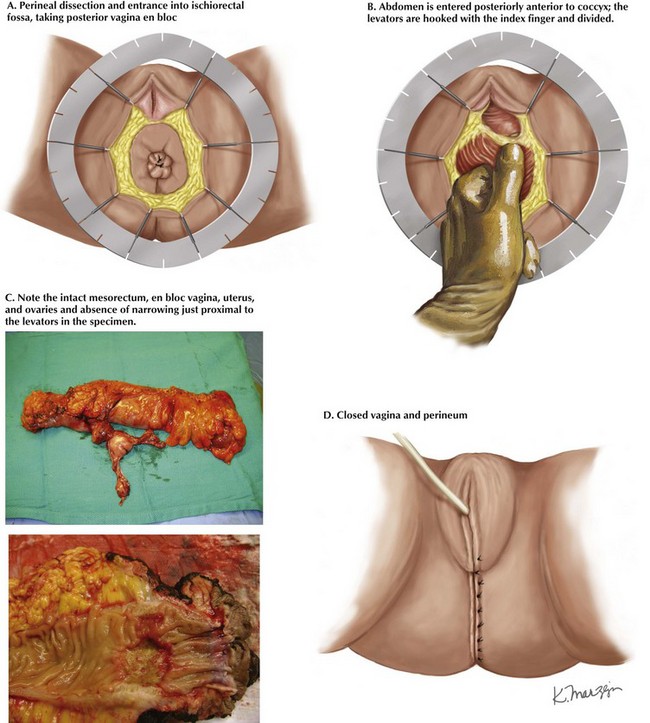

After outlining margins, the skin is scored. The amount of skin that needs to be taken is not great, and usually the anal verge suffices, except with a larger squamous lesion. The dissection is continued until the ischiorectal fossa is entered circumferentially (Fig. 25-5, A). Usually, the posterior dissection is performed first because it has the clearest landmarks. The dissection proceeds to join the abdominal dissection, just above the coccyx. The surgeon continues the lateral dissection up to the lateral origin of the levator muscles, staying in an extra-levator plane. A finger is placed in the patient’s pelvis and hooked behind the levators, and cautery is used to divide the left and right muscles (Fig. 25-5, B).

The anterior dissection is finally undertaken. In the male patient, the urethra is noted by palpation of the Foley catheter, and great care is taken to avoid injury. In the female patient, a finger in the vagina can help to define the anterior plane. After the dissection is completed circumferentially, the specimen is delivered through the perineum and carefully examined for adequacy of margins (Fig. 25-5, C).

Closure of the perineum is accomplished in layers with absorbable sutures. Generous bites are taken from the remaining ischiorectal fat. A deep layer is placed in the subcutaneous fat. The vagina, although somewhat narrowed, can usually be closed in a tubular fashion. The perineum is then closed with interrupted vertical mattress sutures, beginning at the introitus (Fig. 25-5, D).

Han, JG, Want, ZJ, Wei, GH, et al. Randomized clinical trial of conventional versus cylindrical abdominoperineal resection for locally advanced lower rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2012;204:274–282.

Perry, WB, Connaughton, JC. Abdominoperineal resection: how is it done and what are the results? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20(3):213–220.

Stelzner, S, Hellmich, G, Schubert, C, et al. Short-term outcome of extra-levator abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:919–925.