Chapter 1 Abdominal Wall Anatomy and Vascular Supply

1 Clinical Anatomy

1 Overview

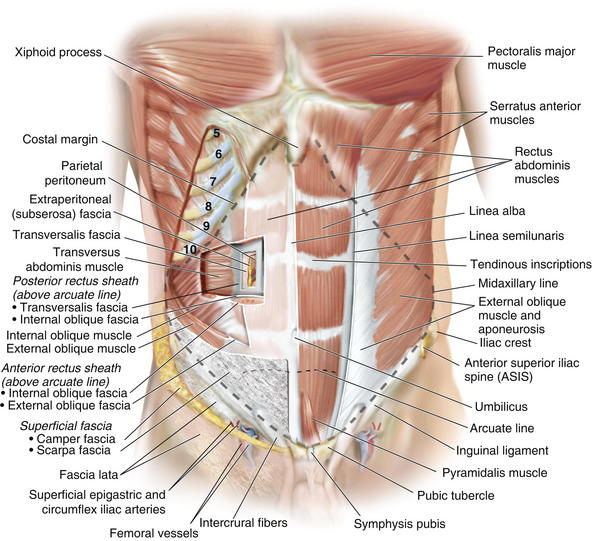

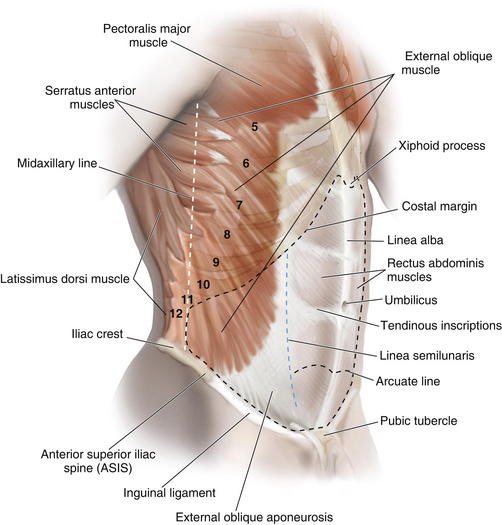

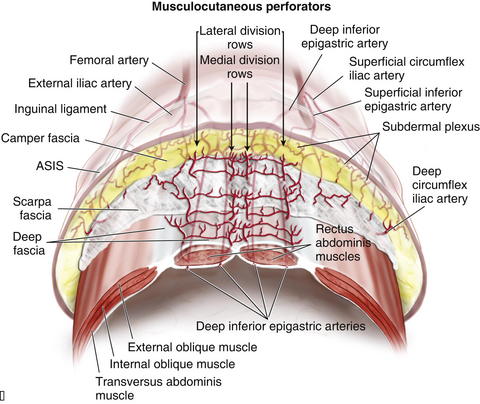

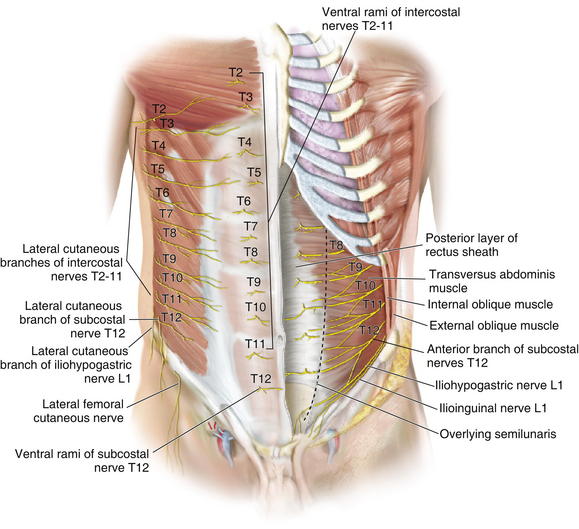

The anterior abdominal wall (Figs. 1-1 to 1-3) is a hexagonal area defined superiorly by the costal margin and xiphoid process; laterally by the midaxillary line; and inferiorly by the symphysis pubis, pubic tubercle, inguinal ligament, anterior superior iliac spine, and iliac crest.

The anterior abdominal wall (Figs. 1-1 to 1-3) is a hexagonal area defined superiorly by the costal margin and xiphoid process; laterally by the midaxillary line; and inferiorly by the symphysis pubis, pubic tubercle, inguinal ligament, anterior superior iliac spine, and iliac crest.2 Superficial Fascial Layers (see Figs. 1-1 and 1-2)

The superficial fascia of the abdominal wall consists of a single layer above the umbilicus, consisting of the fused Camper and Scarpa fasciae.

The superficial fascia of the abdominal wall consists of a single layer above the umbilicus, consisting of the fused Camper and Scarpa fasciae. Below the umbilicus the superficial fascia consists of a fatty outer layer (Camper fascia) and a membranous inner layer (Scarpa fascia).

Below the umbilicus the superficial fascia consists of a fatty outer layer (Camper fascia) and a membranous inner layer (Scarpa fascia). Camper fascia is continuous inferiorly with the superficial thigh fascia and extends inferiorly to the scrotum in males and labia majora in females.

Camper fascia is continuous inferiorly with the superficial thigh fascia and extends inferiorly to the scrotum in males and labia majora in females.3 Deep Fascial Layers (see Figs. 1-1 and 1-2)

Laterally, layers of the abdominal wall deep to superficial fascia include external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and parietal peritoneum.

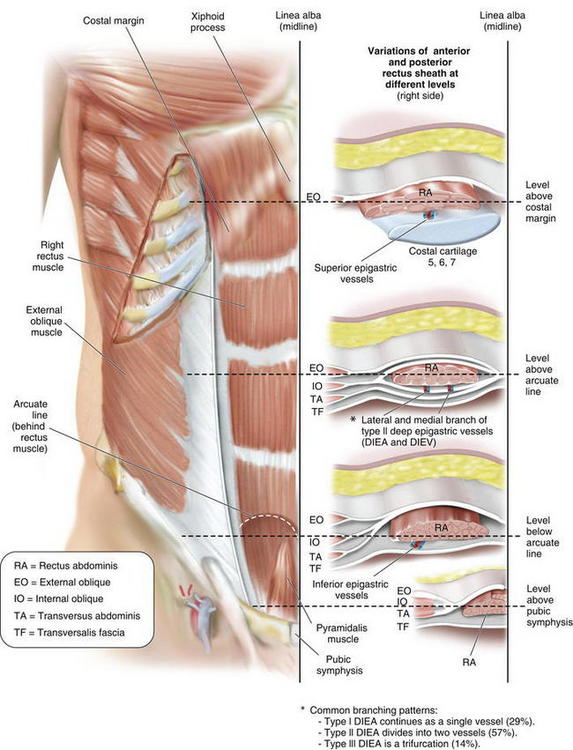

Laterally, layers of the abdominal wall deep to superficial fascia include external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and parietal peritoneum. The arcuate line (see Fig. 1-3) is located midway between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis and is a transition point where the posterior rectus sheath transitions from being the fusion of part of internal oblique fascia and transversalis fascia superiorly to only transversalis fascia inferiorly.

The arcuate line (see Fig. 1-3) is located midway between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis and is a transition point where the posterior rectus sheath transitions from being the fusion of part of internal oblique fascia and transversalis fascia superiorly to only transversalis fascia inferiorly. Above the arcuate line, the anterior rectus sheath consists of external oblique fascia and part of internal oblique fascia. The posterior rectus sheath consists of internal oblique fascia and transversalis fascia. The anterior and posterior layers of the rectus fascia therefore invest the rectus abdominis muscles.

Above the arcuate line, the anterior rectus sheath consists of external oblique fascia and part of internal oblique fascia. The posterior rectus sheath consists of internal oblique fascia and transversalis fascia. The anterior and posterior layers of the rectus fascia therefore invest the rectus abdominis muscles. Below the arcuate line, the external oblique and internal oblique fasciae merge to form the anterior rectus sheath. The posterior rectus sheath consists of transversus abdominis fascia, making this only a thin layer with minimal strength.

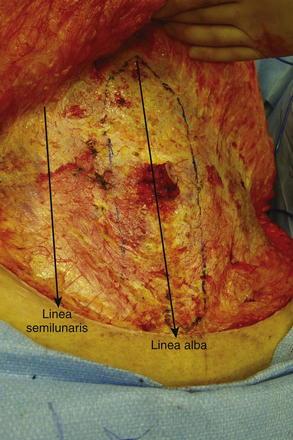

Below the arcuate line, the external oblique and internal oblique fasciae merge to form the anterior rectus sheath. The posterior rectus sheath consists of transversus abdominis fascia, making this only a thin layer with minimal strength. The linea alba results from fusion of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths and lies in the midline, extending cranially from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis caudally Figure 1-4 shows the anterior wall fascia after dissection of the abdominal wall skin and subcutaneous tissue, showing the linea alba and linea semilunaris.

The linea alba results from fusion of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths and lies in the midline, extending cranially from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis caudally Figure 1-4 shows the anterior wall fascia after dissection of the abdominal wall skin and subcutaneous tissue, showing the linea alba and linea semilunaris. Pearls and Pitfalls

Pearls and Pitfalls

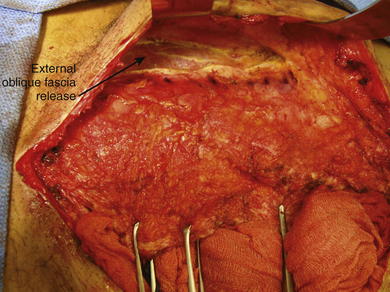

Incision, release, and dissection of the anterior external oblique fascia can be done for repair of ventral hernias. This technique is called the components separation (Fig. 1-5). The incision in the external oblique fascia is made 1 to 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris, and the fascia is released to attain primary closure. Incisions also can be made in the posterior rectus sheath to gain additional length.

4 Abdominal Wall Musculature (see Figs. 1-1 to 1-3)

The paired rectus abdominis muscles are the principal flexors of the anterior abdominal wall. They function to stabilize the pelvis while walking. They also protect the abdominal organs and help in forced expiration.

The paired rectus abdominis muscles are the principal flexors of the anterior abdominal wall. They function to stabilize the pelvis while walking. They also protect the abdominal organs and help in forced expiration. The rectus abdominis muscles originate from the pubic symphysis and pubic crest and insert on the anterior surfaces of the fifth, sixth, and seventh costal cartilages and the xiphoid processes. Laterally, the rectus sheath merges with the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscles to form the linea semilunaris (Fig. 1-4).

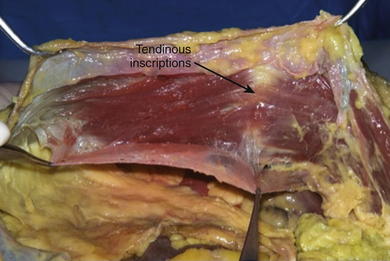

The rectus abdominis muscles originate from the pubic symphysis and pubic crest and insert on the anterior surfaces of the fifth, sixth, and seventh costal cartilages and the xiphoid processes. Laterally, the rectus sheath merges with the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscles to form the linea semilunaris (Fig. 1-4). Three to four tendinous inscriptions, which are adherent to the anterior rectus sheath, interrupt the rectus abdominis along its length (Fig. 1-6).

Three to four tendinous inscriptions, which are adherent to the anterior rectus sheath, interrupt the rectus abdominis along its length (Fig. 1-6). The external oblique muscle is the most superficial and thickest of the three lateral abdominal wall muscles. It originates from the lower eight ribs and courses in an inferomedial direction. Inferiorly it folds back on itself and forms the inguinal ligament, which extends between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle. It is attached medially to the pubic crest.

The external oblique muscle is the most superficial and thickest of the three lateral abdominal wall muscles. It originates from the lower eight ribs and courses in an inferomedial direction. Inferiorly it folds back on itself and forms the inguinal ligament, which extends between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle. It is attached medially to the pubic crest. The internal oblique muscle is deep to the external oblique muscle, and its aponeurosis splits medially above the arcuate line to form part of the anterior rectus sheath and part of the posterior rectus sheath. Below the arcuate line, the inferior oblique aponeurosis does not split and fuses with the external oblique fascia to form the anterior rectus sheath. The internal oblique muscle runs in a superomedial direction, perpendicular to the external oblique muscle. It originates from the thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two thirds of the iliac crest, and lateral half of the inguinal ligament. It inserts on the inferior and posterior borders of the tenth through twelfth ribs superiorly. Inferiorly, the internal oblique inserts on the pectineal line with fibers from the transversus abdominis, forming the conjoint tendon, which inserts on the pubic crest.

The internal oblique muscle is deep to the external oblique muscle, and its aponeurosis splits medially above the arcuate line to form part of the anterior rectus sheath and part of the posterior rectus sheath. Below the arcuate line, the inferior oblique aponeurosis does not split and fuses with the external oblique fascia to form the anterior rectus sheath. The internal oblique muscle runs in a superomedial direction, perpendicular to the external oblique muscle. It originates from the thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two thirds of the iliac crest, and lateral half of the inguinal ligament. It inserts on the inferior and posterior borders of the tenth through twelfth ribs superiorly. Inferiorly, the internal oblique inserts on the pectineal line with fibers from the transversus abdominis, forming the conjoint tendon, which inserts on the pubic crest. The transversus abdominis muscle is the deepest of the three lateral abdominal wall muscles and courses in a horizontal direction. It originates from the anterior three fourths of the iliac crest; lateral third of the inguinal ligament; and inner surface of the lower six costal cartilages, interdigitating with fibers of the diaphragm. The muscle ends medially in a broad flat aponeurosis, merging above the arcuate line with the posterior lamella of the internal oblique aponeurosis and the linea alba. Below the arcuate line, it inserts into the pubic crest and pectineal line, forming the conjoint tendon with the internal oblique.

The transversus abdominis muscle is the deepest of the three lateral abdominal wall muscles and courses in a horizontal direction. It originates from the anterior three fourths of the iliac crest; lateral third of the inguinal ligament; and inner surface of the lower six costal cartilages, interdigitating with fibers of the diaphragm. The muscle ends medially in a broad flat aponeurosis, merging above the arcuate line with the posterior lamella of the internal oblique aponeurosis and the linea alba. Below the arcuate line, it inserts into the pubic crest and pectineal line, forming the conjoint tendon with the internal oblique. The pyramidalis is a small triangular muscle found anterior to the inferior aspect of the rectus abdominis; it is absent in about 20% of the population. It originates from the body of the pubis and inserts into the linea alba inferior to the umbilicus.

The pyramidalis is a small triangular muscle found anterior to the inferior aspect of the rectus abdominis; it is absent in about 20% of the population. It originates from the body of the pubis and inserts into the linea alba inferior to the umbilicus. The semilunar lines are formed by fusion of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis aponeuroses at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis.

The semilunar lines are formed by fusion of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis aponeuroses at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis.5 Neurovascular Supply of the Abdominal Wall

Pearls and Pitfalls

Pearls and Pitfalls

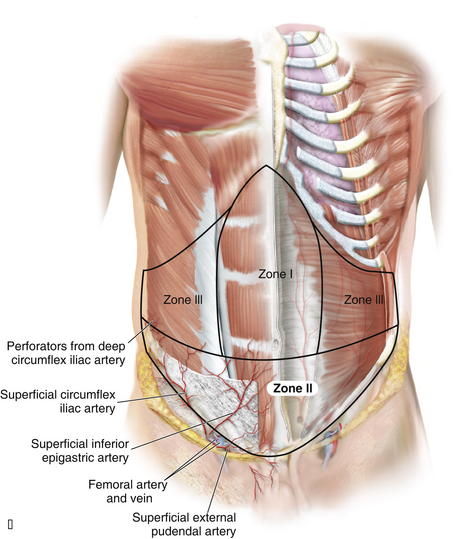

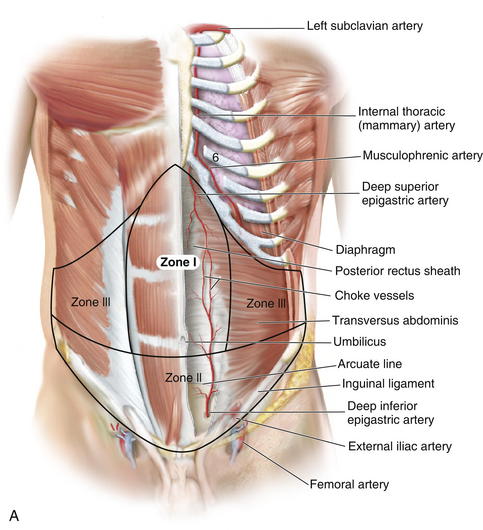

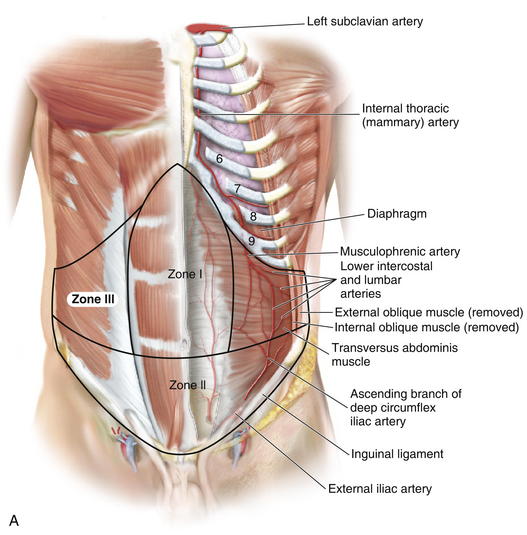

Zone I consists of the upper and midcentral abdominal walls and is supplied by the vertically oriented deep superior (Fig. 1-7, A).and deep inferior epigastric arteries (Fig. 1-7, B).

Zone I consists of the upper and midcentral abdominal walls and is supplied by the vertically oriented deep superior (Fig. 1-7, A).and deep inferior epigastric arteries (Fig. 1-7, B). Zone II consists of the lower abdominal wall and is supplied by the epigastric arcade, superficial inferior epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. Perforators from the deep circumflex iliac arteries also supply a region of skin posterior and cephalad to the anterior superior iliac spine along the axis of the iliac crest.

Zone II consists of the lower abdominal wall and is supplied by the epigastric arcade, superficial inferior epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. Perforators from the deep circumflex iliac arteries also supply a region of skin posterior and cephalad to the anterior superior iliac spine along the axis of the iliac crest. Vascular Supply

Vascular Supply

Knowledge of these zones of blood supply to the anterior abdominal wall is important when planning incisions for surgical procedures. A previous subcostal incision can compromise the circulation to Huger’s zone III of the abdominal wall. In transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap harvest, the presence of a subcostal scar was found to increase donor site complications, with a significantly higher incidence of abdominal wall skin necrosis (25%) compared with patients without abdominal wall scars (5%).

Knowledge of these zones of blood supply to the anterior abdominal wall is important when planning incisions for surgical procedures. A previous subcostal incision can compromise the circulation to Huger’s zone III of the abdominal wall. In transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap harvest, the presence of a subcostal scar was found to increase donor site complications, with a significantly higher incidence of abdominal wall skin necrosis (25%) compared with patients without abdominal wall scars (5%). The superior epigastric artery and deep inferior epigastric arteries lie on the posterior aspect of the rectus abdominis muscles and supply the muscle and overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue through musculocutaneous perforators (Fig. 1-9).

The superior epigastric artery and deep inferior epigastric arteries lie on the posterior aspect of the rectus abdominis muscles and supply the muscle and overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue through musculocutaneous perforators (Fig. 1-9). A study by Saber et al. (2004) provides guidelines for location of the epigastric vessels based on computed tomography (CT) scan data in 100 patients. At the xiphoid process, the superior epigastric arteries (SEA) were 4.41 ± 0.13 cm from the midline on the right and 4.53 ± 0.14 cm from the left. Midway between xiphoid and umbilicus, the SEA was 5.50 ± 0.16 cm on right of midline and 5.36 ± 0.16 cm on the left. At the umbilicus, the epigastric vessels were 5.88 ± 0.14 cm on the right and 5.55 ± 0.13 on left of midline. Midway between umbilicus and symphysis pubis, the inferior epigastric arteries (IEA) were 5.32 ± 0.12 cm on right and 5.25 ± 0.11 cm on left of midline. While at the symphysis pubis, the IEA were 7.47 ± 0.10 cm from the midline on the right and 7.49 ± 0.09 cm from midline on the left side.

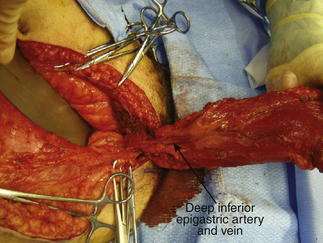

A study by Saber et al. (2004) provides guidelines for location of the epigastric vessels based on computed tomography (CT) scan data in 100 patients. At the xiphoid process, the superior epigastric arteries (SEA) were 4.41 ± 0.13 cm from the midline on the right and 4.53 ± 0.14 cm from the left. Midway between xiphoid and umbilicus, the SEA was 5.50 ± 0.16 cm on right of midline and 5.36 ± 0.16 cm on the left. At the umbilicus, the epigastric vessels were 5.88 ± 0.14 cm on the right and 5.55 ± 0.13 on left of midline. Midway between umbilicus and symphysis pubis, the inferior epigastric arteries (IEA) were 5.32 ± 0.12 cm on right and 5.25 ± 0.11 cm on left of midline. While at the symphysis pubis, the IEA were 7.47 ± 0.10 cm from the midline on the right and 7.49 ± 0.09 cm from midline on the left side. The deep inferior epigastric artery is dominant in the vascular supply of the abdominal compared with the superior epigastric artery. The two arborizing vascular systems converge within the rectus abdominis muscle at a point in between the xiphoid process and umbilicus. In a study by Taylor et al. (2003), the mean diameter of the deep inferior epigastric artery at its point of origin was 3.4 mm, compared to 1.6 mm for the superior epigastric artery, perhaps explaining the dominant arterial supply of the deep inferior epigastric artery.

The deep inferior epigastric artery is dominant in the vascular supply of the abdominal compared with the superior epigastric artery. The two arborizing vascular systems converge within the rectus abdominis muscle at a point in between the xiphoid process and umbilicus. In a study by Taylor et al. (2003), the mean diameter of the deep inferior epigastric artery at its point of origin was 3.4 mm, compared to 1.6 mm for the superior epigastric artery, perhaps explaining the dominant arterial supply of the deep inferior epigastric artery. The deep inferior epigastric artery arises from the medial aspect of the external iliac artery opposite the origin of the deep circumflex iliac artery, approximately 1 cm above the inguinal ligament. It passes superomedially behind the transversalis fascia and towards the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle. It then enters the rectus sheath, passing anterior to the arcuate line, midway between pubis and umbilicus.

The deep inferior epigastric artery arises from the medial aspect of the external iliac artery opposite the origin of the deep circumflex iliac artery, approximately 1 cm above the inguinal ligament. It passes superomedially behind the transversalis fascia and towards the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle. It then enters the rectus sheath, passing anterior to the arcuate line, midway between pubis and umbilicus. The superior epigastric artery originates at the bifurcation of the internal mammary artery into the musculophrenic artery and deep superior epigastric artery, around the region of the sixth costal cartilage. It subsequently passes inferolaterally and pierces the posterior rectus sheath to lie on the posterior surface of the abdominal muscle. It then gives off two or more branches before anastomosing with the branches of the deep inferior epigastric artery.

The superior epigastric artery originates at the bifurcation of the internal mammary artery into the musculophrenic artery and deep superior epigastric artery, around the region of the sixth costal cartilage. It subsequently passes inferolaterally and pierces the posterior rectus sheath to lie on the posterior surface of the abdominal muscle. It then gives off two or more branches before anastomosing with the branches of the deep inferior epigastric artery. The superior epigastric artery, when described, refers in general to the deep superior epigastric artery. A superficial superior epigastric artery has been noted in anatomic studies, but it is not clinically significant.

The superior epigastric artery, when described, refers in general to the deep superior epigastric artery. A superficial superior epigastric artery has been noted in anatomic studies, but it is not clinically significant. The musculophrenic artery passes inferolaterally behind the seventh, eighth, and ninth costal cartilages and provides large branches to the intercostal spaces, which become continuous with the posterior intercostal vessels. Together with the lumbar arteries, it supplies the lateral part of the abdominal wall. The musculophrenic artery provides an alternative vascular supply for a pedicled TRAM flap when the proximal portion of the internal mammary artery has been divided or is obstructed.

The musculophrenic artery passes inferolaterally behind the seventh, eighth, and ninth costal cartilages and provides large branches to the intercostal spaces, which become continuous with the posterior intercostal vessels. Together with the lumbar arteries, it supplies the lateral part of the abdominal wall. The musculophrenic artery provides an alternative vascular supply for a pedicled TRAM flap when the proximal portion of the internal mammary artery has been divided or is obstructed. Three patterns of blood supply of the rectus abdominis muscle were described by Taylor et al. (2003), based on divisions of the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) at the level of the arcuate line. In type 1 (29%), there was a single intramuscular artery. In type 2 (57%), the DIEA divided at the arcuate line into two major intramuscular vessels. In type 3 (14%) the DIEA divided into three branches at the arcuate line.

Three patterns of blood supply of the rectus abdominis muscle were described by Taylor et al. (2003), based on divisions of the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) at the level of the arcuate line. In type 1 (29%), there was a single intramuscular artery. In type 2 (57%), the DIEA divided at the arcuate line into two major intramuscular vessels. In type 3 (14%) the DIEA divided into three branches at the arcuate line. Musculocutaneous perforators arise from the deep inferior epigastric artery and lie in a medial and lateral subdivision in the form of longitudinal rows of perforators parallel to the sagittal plane.

Musculocutaneous perforators arise from the deep inferior epigastric artery and lie in a medial and lateral subdivision in the form of longitudinal rows of perforators parallel to the sagittal plane. Medial row perforators, in general, tend to have a vascular territory that is larger and crosses the midline, well perfusing Hartrampf zones I and II.

Medial row perforators, in general, tend to have a vascular territory that is larger and crosses the midline, well perfusing Hartrampf zones I and II. Lateral row perforators tend to have a zone of perfusion that is localized to a hemiabdomen and may be used preferentially when a smaller flap is required.

Lateral row perforators tend to have a zone of perfusion that is localized to a hemiabdomen and may be used preferentially when a smaller flap is required. A study by Chowdhry et al. (2010) reported that the DIEA encountered the lateral border of the rectus abdominis at a mean distance of 10.45 ± 1.58 cm from the umbilicus, with the first perforator transversing the rectus abdominis muscle around 7.4 ± 1.64 cm from the umbilicus.

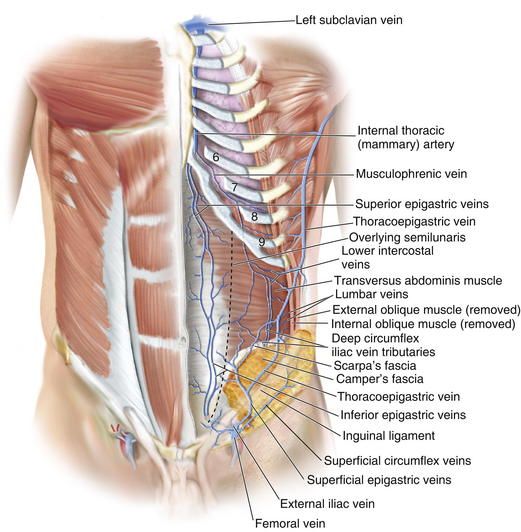

A study by Chowdhry et al. (2010) reported that the DIEA encountered the lateral border of the rectus abdominis at a mean distance of 10.45 ± 1.58 cm from the umbilicus, with the first perforator transversing the rectus abdominis muscle around 7.4 ± 1.64 cm from the umbilicus. Veins draining the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 1-10) run as venae comitantes, accompanying the perforators and subsequently main arteries of the deep inferior and superior epigastric arteries. These ultimately drain into the azygos system and external iliac veins.

Veins draining the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 1-10) run as venae comitantes, accompanying the perforators and subsequently main arteries of the deep inferior and superior epigastric arteries. These ultimately drain into the azygos system and external iliac veins. The superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA) arises from the external iliac artery or superficial circumflex iliac artery, and together with its accompanying vein, lies in the plane between the Camper and Scarpa fasciae on each side, lateral to the rectus abdominis muscles. These provide an accessory blood supply to the anterior abdominal wall, which may be used in the harvesting of flaps.

The superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA) arises from the external iliac artery or superficial circumflex iliac artery, and together with its accompanying vein, lies in the plane between the Camper and Scarpa fasciae on each side, lateral to the rectus abdominis muscles. These provide an accessory blood supply to the anterior abdominal wall, which may be used in the harvesting of flaps. The SIEA was reported to have a mean diameter of 0.6 mm, with a diameter >1.5 mm only in 24% of patients. Location of the SIEA is highly variable, with a mean position 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris (range 0 to 8 cm).

The SIEA was reported to have a mean diameter of 0.6 mm, with a diameter >1.5 mm only in 24% of patients. Location of the SIEA is highly variable, with a mean position 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris (range 0 to 8 cm). The location of the superficial inferior epigastric vein (SIEV) is highly variable compared with the SIEA, with the distance between SIEA and SIEV ranging from 0.3 to 8.5 cm apart. Unlike the veins accompanying the other arteries supplying the anterior abdominal wall, the SIEV often runs a distance away from its corresponding artery, the SIEA.

The location of the superficial inferior epigastric vein (SIEV) is highly variable compared with the SIEA, with the distance between SIEA and SIEV ranging from 0.3 to 8.5 cm apart. Unlike the veins accompanying the other arteries supplying the anterior abdominal wall, the SIEV often runs a distance away from its corresponding artery, the SIEA. Nerve Supply (Fig. 1-11)

Nerve Supply (Fig. 1-11)

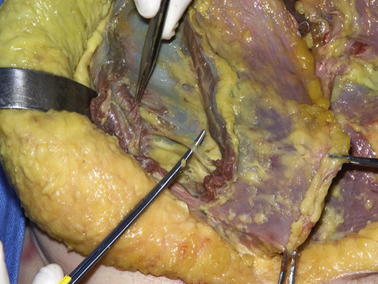

Sensory innervation of the abdominal wall is derived from the anterior branches of the intercostals and subcostal nerves, from T7 to L1. These nerves run together with the intercostal and lumbar arteries in the plane between the internal oblique and transversalis muscles. Figure 1-12 shows the motor nerves to the rectus abdominis muscle. The internal oblique muscle has been divided, showing the nerve deep to the internal oblique muscle and superficial to the transversus abdominis muscle.

Sensory innervation of the abdominal wall is derived from the anterior branches of the intercostals and subcostal nerves, from T7 to L1. These nerves run together with the intercostal and lumbar arteries in the plane between the internal oblique and transversalis muscles. Figure 1-12 shows the motor nerves to the rectus abdominis muscle. The internal oblique muscle has been divided, showing the nerve deep to the internal oblique muscle and superficial to the transversus abdominis muscle. Lateral cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves supply the lateral areas of the abdominal wall.

Lateral cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves supply the lateral areas of the abdominal wall. Motor innervation is supplied by the seventh through twelfth intercostal nerves, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves.

Motor innervation is supplied by the seventh through twelfth intercostal nerves, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves. The rectus abdominis muscle is innervated segmentally by ventral rami of the lower six intercostal nerves.

The rectus abdominis muscle is innervated segmentally by ventral rami of the lower six intercostal nerves. The internal oblique is innervated by the lower thoracic intercostal nerves (T6 to T12) and the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves.

The internal oblique is innervated by the lower thoracic intercostal nerves (T6 to T12) and the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves.2 Abdominal Wall Physiology

1 Function in Respiration

The abdominal wall plays an accessory role to the intercostal muscles, thorax, and diaphragm in respiration.

The abdominal wall plays an accessory role to the intercostal muscles, thorax, and diaphragm in respiration. The diaphragm maintains a constant positive pressure differential between the abdomen and thorax, increasing the volume of the thorax in inspiration and decreasing the volume of the thorax in expiration.

The diaphragm maintains a constant positive pressure differential between the abdomen and thorax, increasing the volume of the thorax in inspiration and decreasing the volume of the thorax in expiration. The abdominal wall primarily functions in expiration, whereas the transversus abdominis and external and internal obliques raise intraabdominal pressure to meet increased demands of breathing during exercise. This increase in intraabdominal pressure is transmitted through the diaphragm to the thorax and forces air from the lungs.

The abdominal wall primarily functions in expiration, whereas the transversus abdominis and external and internal obliques raise intraabdominal pressure to meet increased demands of breathing during exercise. This increase in intraabdominal pressure is transmitted through the diaphragm to the thorax and forces air from the lungs. In the absence of exertion or exercise, expiration is largely passive, and relies on relaxation of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm.

In the absence of exertion or exercise, expiration is largely passive, and relies on relaxation of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm. In inspiration, the abdominal wall provides anterior support for the abdominal cavity, allowing for generation of a pressure differential between the abdomen and thorax through the diaphragm.

In inspiration, the abdominal wall provides anterior support for the abdominal cavity, allowing for generation of a pressure differential between the abdomen and thorax through the diaphragm. The large mass of the intraabdominal contents hydraulically transmits a negative pressure to the thorax at steady state, through gravity, when a person is upright. When a person is supine, this effect is diminished, therefore resulting in a decrease of functional respiratory capacity of the lungs by around 15% to 20% of vital capacity.

The large mass of the intraabdominal contents hydraulically transmits a negative pressure to the thorax at steady state, through gravity, when a person is upright. When a person is supine, this effect is diminished, therefore resulting in a decrease of functional respiratory capacity of the lungs by around 15% to 20% of vital capacity.2 Muscle Function

The musculature of the anterior abdominal wall works in a synkinetic fashion to protect intraabdominal contents and also increase abdominal pressure where required.

The musculature of the anterior abdominal wall works in a synkinetic fashion to protect intraabdominal contents and also increase abdominal pressure where required. An increase in intraabdominal pressure facilitates expiration, micturition, defecation, and even parturition.

An increase in intraabdominal pressure facilitates expiration, micturition, defecation, and even parturition. The diaphragm, iliopsoas, and quadratus lumborum muscle form a kinetic chain that integrates upper and lower body activity, allowing coordinated movement and weight shifts.

The diaphragm, iliopsoas, and quadratus lumborum muscle form a kinetic chain that integrates upper and lower body activity, allowing coordinated movement and weight shifts. Together with this kinetic chain, the rectus abdominis muscle stabilizes the pelvis during walking, running, and jumping.

Together with this kinetic chain, the rectus abdominis muscle stabilizes the pelvis during walking, running, and jumping. A number of studies have been performed to evaluate function of the abdominal wall after bilateral TRAM flaps for breast reconstruction. Although results are highly variable, it is generally agreed that loss of both rectus muscles results in some degree of pain, back pain, and decreased flexor strength of the anterior abdominal wall.

A number of studies have been performed to evaluate function of the abdominal wall after bilateral TRAM flaps for breast reconstruction. Although results are highly variable, it is generally agreed that loss of both rectus muscles results in some degree of pain, back pain, and decreased flexor strength of the anterior abdominal wall.3 Abdominal Wall Disruption Relevant to Anatomy

1 Rectus Diastasis

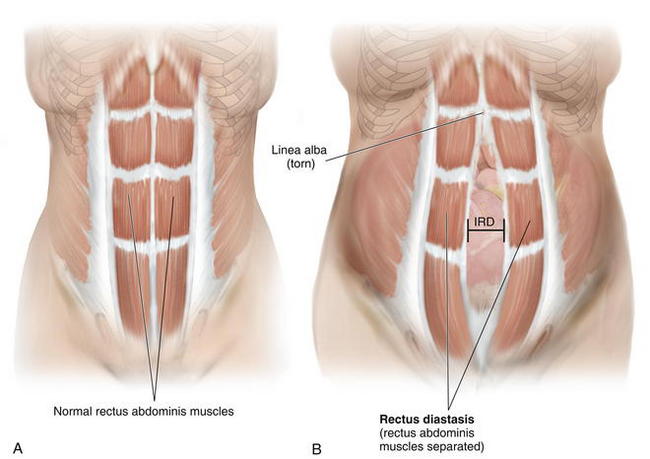

Diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles is defined as separation of the paired recti at the midline (Fig. 1-13).

Diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles is defined as separation of the paired recti at the midline (Fig. 1-13). The inter-recti distance (IRD) has been reported to be up to 58 mm in the antenatal period, with a continuing increase in IRD up to four times in the postpartum period.

The inter-recti distance (IRD) has been reported to be up to 58 mm in the antenatal period, with a continuing increase in IRD up to four times in the postpartum period. Severe cases in adults, typically in postpartum women, can be treated by plication of the rectus abdominis muscles.

Severe cases in adults, typically in postpartum women, can be treated by plication of the rectus abdominis muscles. Another reported association with diastasis recti is abdominal aortic aneurysm, particularly in males.

Another reported association with diastasis recti is abdominal aortic aneurysm, particularly in males.2 Ventral Hernia

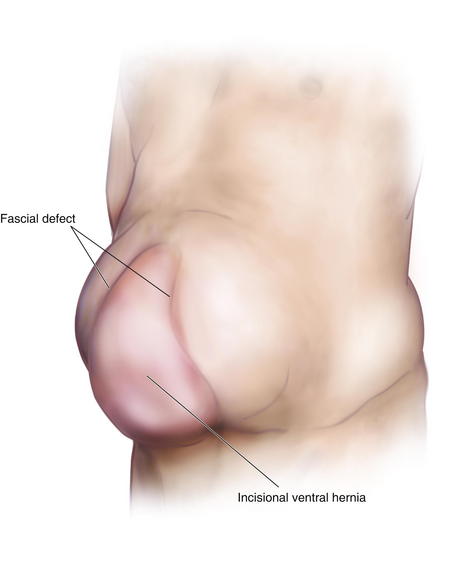

Ventral hernia typically develops as an incisional hernia, following a midline laparotomy through the linea alba; it is due to incomplete healing that results in a fascial defect.

Ventral hernia typically develops as an incisional hernia, following a midline laparotomy through the linea alba; it is due to incomplete healing that results in a fascial defect. Greater than 10% of patients undergoing abdominal surgical procedures develop incisional hernias (>150,000 incisional hernias per year).

Greater than 10% of patients undergoing abdominal surgical procedures develop incisional hernias (>150,000 incisional hernias per year). Risk factors for developing an incisional hernia are obesity, smoking, aneurysmal disease, malnourishment, steroid dependency, renal disease, and malignancy.

Risk factors for developing an incisional hernia are obesity, smoking, aneurysmal disease, malnourishment, steroid dependency, renal disease, and malignancy. Patients present with a mass protruding through the fascia defect and causing localized protuberance of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 1-14).

Patients present with a mass protruding through the fascia defect and causing localized protuberance of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 1-14). Repair can be achieved with laparoscopic or open ventral hernia repairs with or without mesh or components separation techniques.

Repair can be achieved with laparoscopic or open ventral hernia repairs with or without mesh or components separation techniques. Optimization of nutrition is essential for wound healing after reconstructive surgery in the anterior abdominal wall. During closure, it is important to ensure proper alignment of layers of the abdominal wall and tension-free closure. Meticulous surgical technique and avoidance of smoking in patients before and after surgery minimize the incidence of abdominal wall complications.

Optimization of nutrition is essential for wound healing after reconstructive surgery in the anterior abdominal wall. During closure, it is important to ensure proper alignment of layers of the abdominal wall and tension-free closure. Meticulous surgical technique and avoidance of smoking in patients before and after surgery minimize the incidence of abdominal wall complications.3 Physiology of Ventral Hernia Formation

Most incisional hernias resulting from disruption of laparotomy wounds begin forming within 30 days after surgery.

Most incisional hernias resulting from disruption of laparotomy wounds begin forming within 30 days after surgery. In mechanical failure of the midline laparotomy wound, fibrosis, myopathic disuse atrophy, and change in muscle fiber type occur in abdominal wall musculature.

In mechanical failure of the midline laparotomy wound, fibrosis, myopathic disuse atrophy, and change in muscle fiber type occur in abdominal wall musculature. Abnormal load signaling, together with the above pathologic changes, results in reduced abdominal wall compliance.

Abnormal load signaling, together with the above pathologic changes, results in reduced abdominal wall compliance. Animal studies confirm lateral abdominal wall shortening and atrophy of internal oblique muscles, leading to decreased extensibility and increased stiffness of the abdominal wall. This results in persistent mechanical disruption of the hernia at a lower force compared with nonherniated abdominal walls.

Animal studies confirm lateral abdominal wall shortening and atrophy of internal oblique muscles, leading to decreased extensibility and increased stiffness of the abdominal wall. This results in persistent mechanical disruption of the hernia at a lower force compared with nonherniated abdominal walls.4 Congenital Abnormalities

Omphalocele is the protrusion of abdominal wall contents from a midline defect in the abdominal wall at the base of the umbilicus. The herniated contents are covered by a very thin membrane of tissue and can become dry and necrotic after birth. In infants with omphalocele, the incidence of other congenital anomalies, such as bowel atresia, chromosomal abnormalities, and cardiac and renal anomalies, is very high (up to 70%).

Omphalocele is the protrusion of abdominal wall contents from a midline defect in the abdominal wall at the base of the umbilicus. The herniated contents are covered by a very thin membrane of tissue and can become dry and necrotic after birth. In infants with omphalocele, the incidence of other congenital anomalies, such as bowel atresia, chromosomal abnormalities, and cardiac and renal anomalies, is very high (up to 70%). Gastroschisis is the protrusion of abdominal wall contents through a defect in the abdominal wall that is NOT midline, usually to the right of the umbilicus. No membrane covers the abdominal wall contents, and the bowel is usually very edematous and inflamed. There are no associated congenital anomalies in these infants.

Gastroschisis is the protrusion of abdominal wall contents through a defect in the abdominal wall that is NOT midline, usually to the right of the umbilicus. No membrane covers the abdominal wall contents, and the bowel is usually very edematous and inflamed. There are no associated congenital anomalies in these infants.Atisha D., Alderman A.K. A systematic review of abdominal wall function following abdominal flaps for post mastectomy breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:222-230.

Blanchard P.D. Diastasis recti abdominis in HIV-infected men with lipodystrophy. HIV Med. 2005;6:54-56.

Boyd J.B., Taylor G.I., Corlett R. The vascular territories of the superior epigastric and the deep inferior epigastric systems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:1-16.

Chowdhry S., Hazani R., Collis P., Wilhelmi B.J. Anatomical landmarks for safe elevation of the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap: a cadaveric study. Eplasty. 2010;10:e41.

DuBay D.A., Choi W., Urbanchek M.G., et al. Incisional herniation induces decreased abdominal wall compliance via oblique muscle atrophy and fibrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:140-146.

Ducic I., Moxley M., Al-Attar A. Algorithm for treatment of postoperative incisional groin pain after cesarean delivery or hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:27-31.

El-Mrakby H.H., Milner R.H. The vascular anatomy of the lower anterior abdominal wall: a microdissection study on the deep inferior epigastric vessels and the perforator branches. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:539-543.

Franz M.G. The biology of hernia formation. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1-15.

Hartrampf C.R., Scheflan M., Black P.W. Breast reconstruction with a transverse abdominal island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:216-225.

Hsia M., Jones S. Natural resolution of rectus abdominis diastasis. Two single case studies. Aust J Physiother. 2000;46:301-307.

Huger W.E.Jr. The anatomic rationale for abdominal lipectomy. Am Surg. 1979;45:612-617.

Losken A., Carlson G.W., Jones G.E., Culbertson J.H., Schoemann M., Bostwick J.3rd. Importance of right subcostal incisions in patients undergoing TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:115-119.

Moesbergen T., Law A., Roake J., Lewis D.R. Diastasis recti and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Vascular. 2009;17:325-329.

Moon H.K., Taylor G.I. The vascular anatomy of rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flaps based on the deep superior epigastric system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:815-832.

Ramirez O.M., Ruas E., Dellon A.L. “Components separation” method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:519-526.

Rozen W.M., Chubb D., Grinsell D., Ashton M.W. The variability of the superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA) and its angiosome: A clinical anatomical study. Microsurgery. 2010 Jan 7. [Epub ahead of print]

Saber A.A., Meslemani A.M., Davis R., Pimental R. Safety zones for anterior abdominal wall entry during laparoscopy: a CT scan mapping of epigastric vessels. Ann Surg. 2004;239:182-185.

Schneid H., Vazquez M.P., Vacher C., Gormelen M., Cabrol S., Le Bouc Y. The Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome phenotype and the risk of cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:411-415.

Taylor G.I. The angiosomes of the body and their supply to perforator flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:331-342.

Wong C., Saint-Cyr M., Mojallal A., et al. Perforasomes of the DIEP flap: vascular anatomy of the lateral versus medial row perforators and clinical implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:772-782.