Abdominal Repair of Vesicovaginal and Vesicouterine Fistula

Abdominal Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

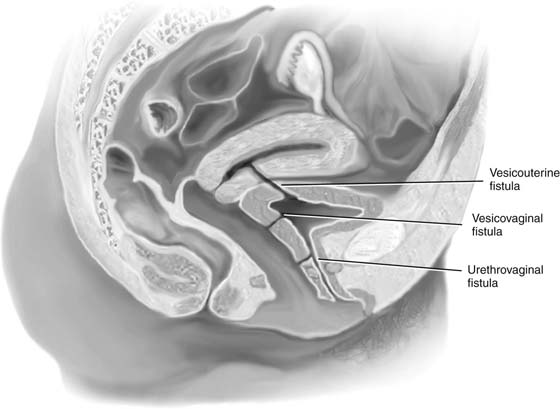

Lower urinary tract fistulas can communicate with the vagina or the uterus (Fig. 89–1). Although the indications for abdominal repair of vesicovaginal fistula are somewhat controversial, certain conditions involving the bladder are best approached via an abdominal route. These include high and inaccessible fistulas, multiple fistulas, involvement of uterus or bowel, and the need for ureteral reimplantation.

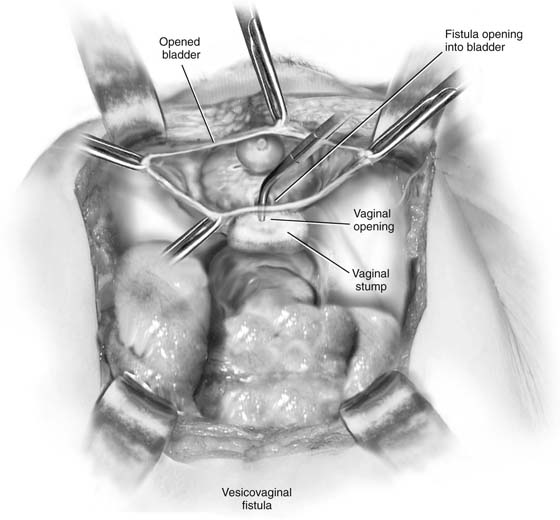

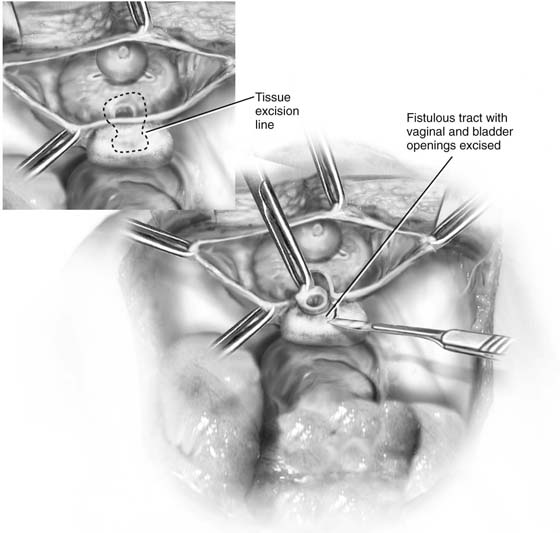

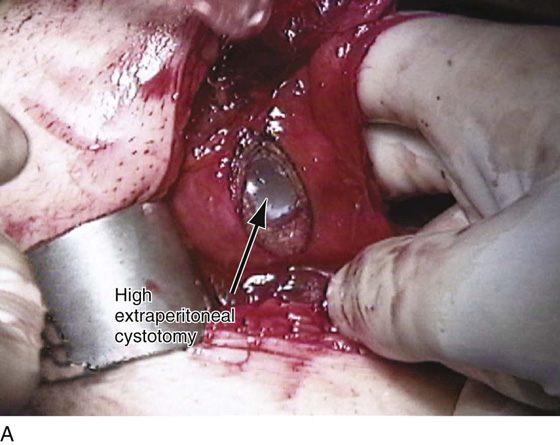

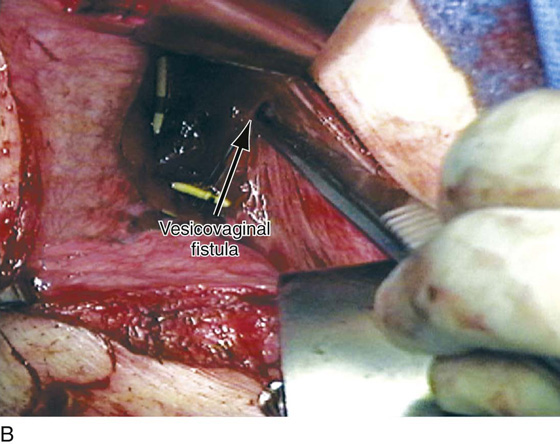

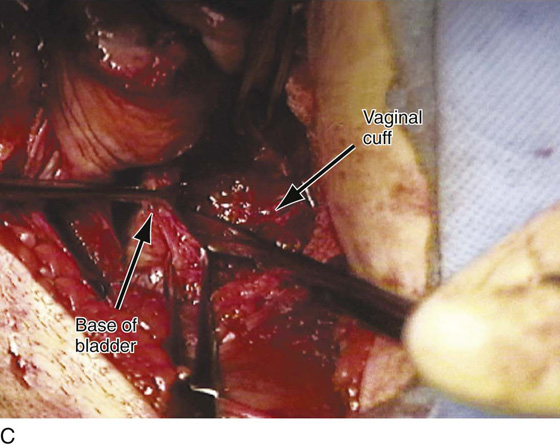

A midline or transverse skin incision can be made. A midline incision will allow easier access to the abdomen for retrieval and mobilization of omentum. If a transverse incision is utilized, often a muscle-splitting incision such as a Maylard or Cherney incision (Fig. 89–2) will facilitate exposure. Once the peritoneum has been opened, the bowel is packed posteriorly and usually a self-retaining retractor is placed. The bladder is then exposed, and a high extraperitoneal intentional cystotomy is made (see previous section on opening and closing the bladder). The fistulous tract is then visualized from the inside of the bladder (Figs. 89–3 and 89–4). If it is in close proximity to the ureteral orifices, ureteral stents should be placed (Fig. 89–5). They can be placed via a cystoscopic approach or intraoperatively via a transvesical approach. The bladder incision is then taken down along the back of the bladder all the way to the fistulous tract (Figs. 89–6 and 89–7). The fistulous tract is completely excised, and the vagina is sharply mobilized off the back of the bladder (Fig. 89–8). A pack or EEA (end-to-end anastomosis) sizer placed in the vagina will produce vaginal distention and facilitates countertraction, which assists the dissection. Traction and countertraction on the vagina and bladder facilitate sharp accurate separation of these two surfaces (Fig. 89–9). It is important to proceed with this dissection well beyond any scarification produced by the fistula (see Figs. 89–9 and 89–10). The vagina is then closed with interrupted 2-0 absorbable sutures, preferably in two layers (see Figs. 89–10 and 89–11). The bladder is closed with 3-0 absorbable sutures in a running fashion or with interrupted sutures. The bladder is also preferably closed in two layers (see Figs. 89–10 through 89–12). It is usually advantageous to mobilize a piece of omentum down to the site of the fistula repair. It is sutured to the anterior wall of the vagina or the posterior wall of the bladder to thus give additional blood supply and a tissue barrier between the suture lines (Figs. 89–13 and 89–14). Fig. 89–15 shows the inside of the bladder after closure and repair of the fistula. Fig. 89–16 is a drawing of the completed repair. Fig. 89–17 reviews again, in a stepwise fashion, the abdominal repair of a vesicovaginal fistula. Catheter drainage may be accomplished with a transurethral or suprapubic catheter (or both), depending on the extent and circumstances of the repair.

FIGURE 89–1 Lower urinary tract fistulas can communicate with the vagina or the uterus. The extent of the fistula and the anatomic location are important factors to be considered when deciding whether to approach the repair vaginally or transabdominally.

FIGURE 89–2 Low transverse muscle-cutting incision of the Cherney variety. Note that the muscle is detached from the pubic bone very low near its insertion. The peritoneum is then usually opened transversely.

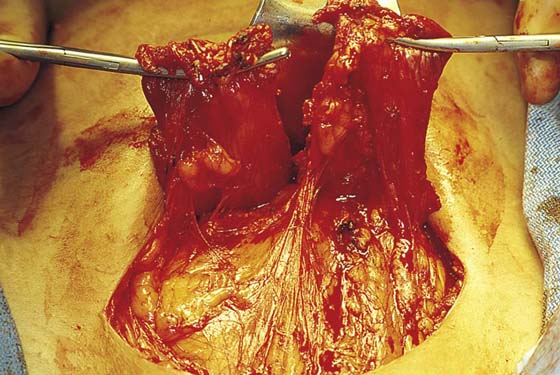

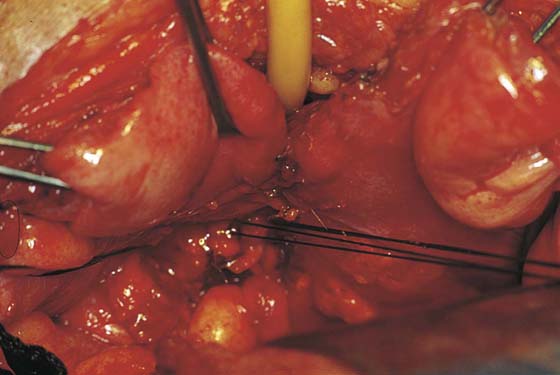

FIGURE 89–3 View of the inside of the bladder in a patient with multiple vesicovaginal fistulas involving the lowest portion of the bladder base just above the trigone. These particular fistulas occurred after an abdominal hysterectomy for severe endometriosis in which the bladder wall was most likely included in the sutures utilized to close the vaginal cuff. Note the stent in the right ureter.

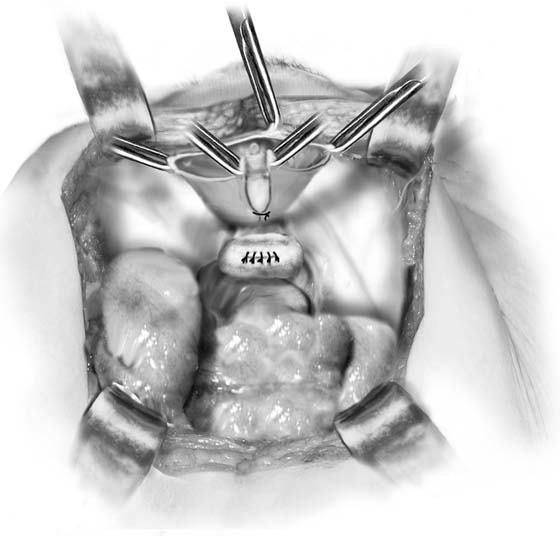

FIGURE 89–4 Drawing showing the inside of the bladder with a fistulous tract into the vagina.

FIGURE 89–5 Inside view of the bladder. Both ureters have now been catheterized secondary to the close proximity of the fistulous tracts to the trigone and ureteral orifices. An incision has been initiated down the back of the bladder toward the fistulous tracts.

FIGURE 89–6 The back wall of the bladder has been cut down to the level of the fistulous tracts. Note that two probes have been placed into the fistulous tracts.

FIGURE 89–7 Sharp dissection has been used to completely mobilize the vaginal cuff from the back of the bladder. Multiple probes demonstrate the fistulous tracts in this particular case. It is very important to continue the dissection of the bladder off the vagina wall beyond the lowest portion of scarification, thus allowing bladder closure without tension.

FIGURE 89–8 Fistulous tract and scarred vagina and bladder are excised.

FIGURE 89–9 Mobilization of the bladder and excision of the fistulous tract have been completed. An EEA sizer was placed in the vagina to facilitate sharp dissection of the bladder off the vagina. Note that dissection has been extended beyond the lowest portion of the fistulous tract.

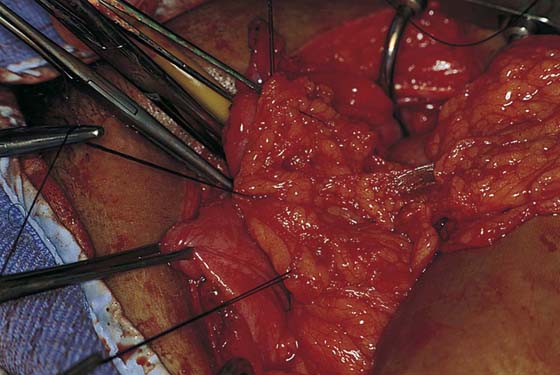

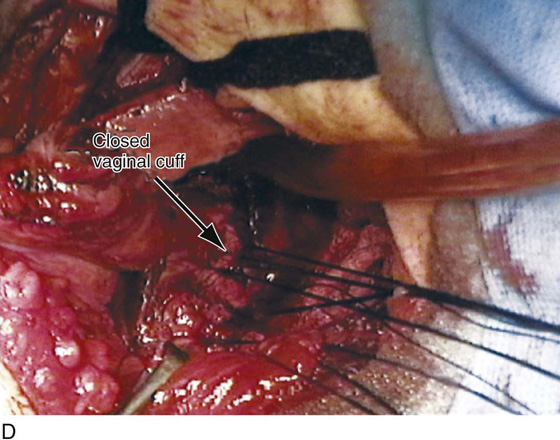

FIGURE 89–10 The vaginal cuff has been closed with interrupted absorbable sutures, which are tagged in this photograph. The lowest portion of the bladder incision has been closed with interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures.

FIGURE 89–11 Dissection has been completed, and the fistulous tract has been excised. The vagina has been closed, and closure of the back of the bladder has been initiated. Note that dissection has extended well below the level of the fistula.

FIGURE 89–12 Closure of the lower part of the bladder viewed from the inside. Because this is a very dependent portion of the bladder, it is probably best to place the sutures in the submucosa if possible.

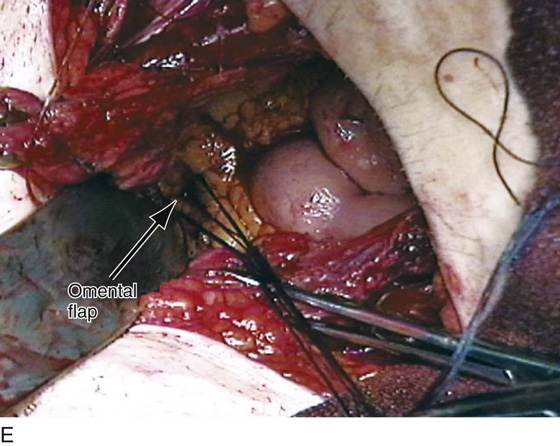

FIGURE 89–13 Omentum is mobilized down into the pelvis.

FIGURE 89–14 Omentum is fixed to the top of the vagina and will act as interposition tissue between the vagina and the bladder.

FIGURE 89–15 Inside of the bladder viewed from the dome after completion of the repair. Note that the bladder has been repaired with very minimal distortion of the trigone.

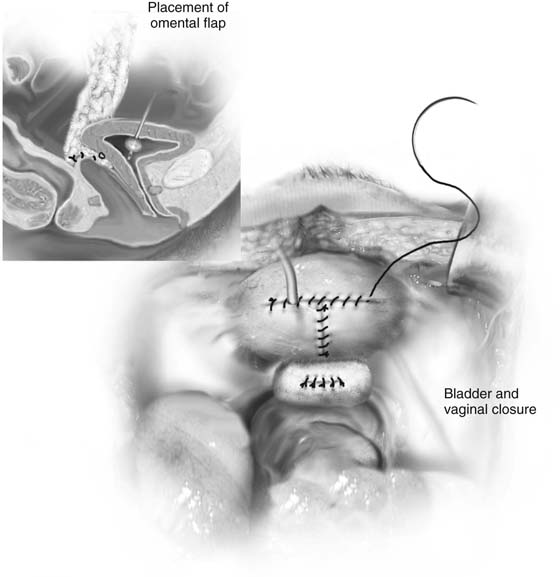

FIGURE 89–16 Drawing of the completed repair. Note the closure of the bladder and vagina with interposition of an omental flap (see inset).

FIGURE 89–17 Abdominal repair of vesicovaginal fistula. A. The repair begins with high extraperitoneal cystotomy to visualize the inside of the bladder and identify the exact location of the fistula. B. The fistula has been identified at its intravesical portion. C. Sharp dissection with a scalpel is utilized to mobilize the scarred vagina away from the base of the bladder. It is very important to extend this dissection to a level well below the scarification to allow for appropriate healing of the bladder and the vaginal cuff. D. The vaginal cuff has been closed with interrupted 2-0 delayed absorbable sutures. E. The back of the bladder has been closed as has the vaginal cuff, and an omental flap has been brought down to be fixed to the anterior aspect of the vaginal cuff as an interposition between the vagina and the base of the bladder.

Repair of Vesicouterine Fistula

Fistulas between the bladder and uterus usually result from obstetric trauma, particularly bladder injuries at cesarean section. Extravasation of urine, superimposed infection, and subsequent dehiscence of the uterine incision constitute the most likely sequence of events in formation of the fistula. Women with vesicouterine fistulas may have cyclic hematuria (menouria; Youssef syndrome). Incontinence or loss of urine through the cervix may at times be absent secondary to a valve mechanism. The tract between the bladder and the uterus is best demonstrated by hysterosalpingography. Small fistulas can heal spontaneously with long-term bladder drainage or hormonal suppression of menstruation for a few months.

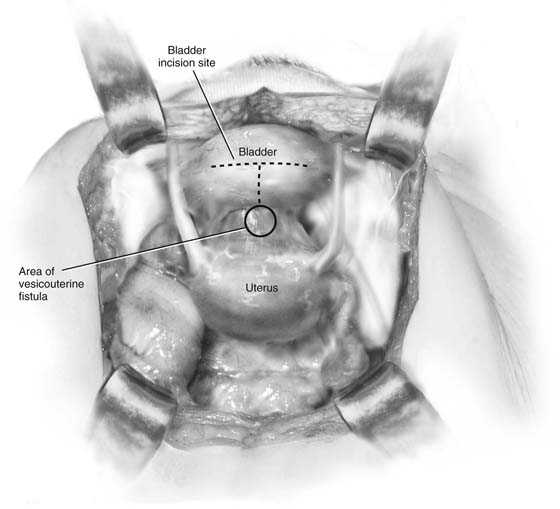

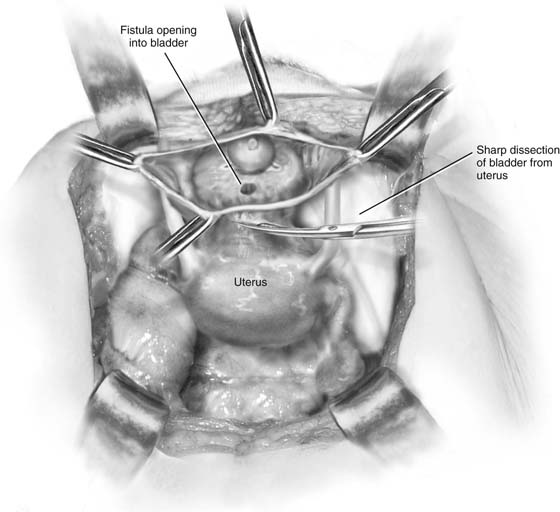

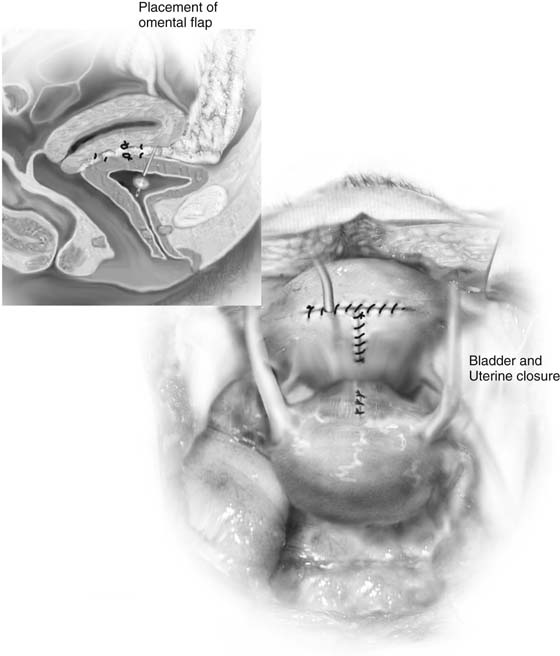

Surgical repair of a vesicouterine fistula is very similar to abdominal repair of a vesicovaginal fistula. A transverse or longitudinal skin incision is made. The peritoneum is opened, and a high cystotomy is made in the extraperitoneal portion of the bladder (see Fig. 89–17A). The fistulous tract is then identified, and sharp dissection is used to dissect between the bladder and the uterus (Figs. 89–18 through 89–20). Once the bladder is completely mobilized off the uterus and the fistulous tract has been excised (Fig. 89–21), the bladder is closed in two layers with interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures. This is followed by interrupted closure of the defect in the uterus. The repair is completed by the interposition of a piece of omentum between the two suture lines (Fig. 89–22). If the patient is not desirous of future fertility, abdominal hysterectomy with closure of the bladder defect is the definitive therapy for a vesicouterine fistula.

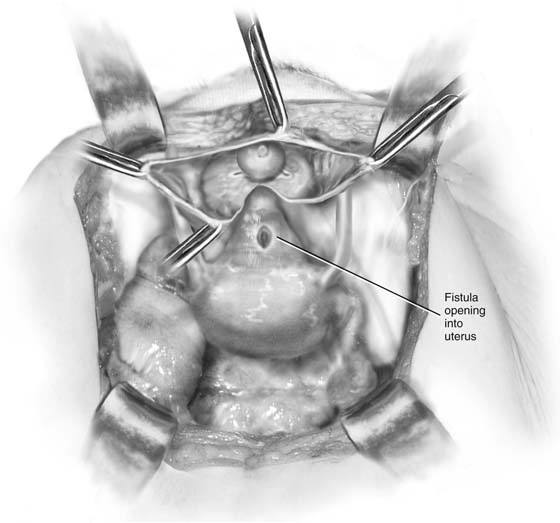

FIGURE 89–18 Vesicouterine fistula between the lower uterine segment and possibly the upper cervix and the base of the bladder. Dotted line shows the bladder incisions used to expose the fistula.

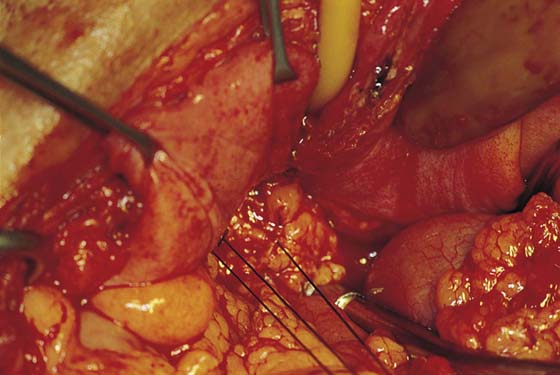

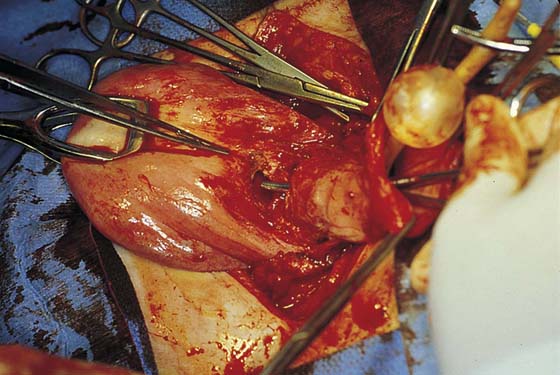

FIGURE 89–19 A high cystotomy has been made and sharp dissection used to separate the bladder from the uterus.

FIGURE 89–20 Vesicouterine fistula. Note that a high cystotomy has been made and a probe has been placed from the inside of the bladder through the fistulous tract into the uterus.

FIGURE 89–21 Sharp dissection has been completed, as there is complete separation of the bladder and the uterus.

FIGURE 89–22 Both bladder and uterus are closed in two layers. Inset shows omental flap interposed between the two structures.