Abdominal Pain

Perspective

Epidemiology

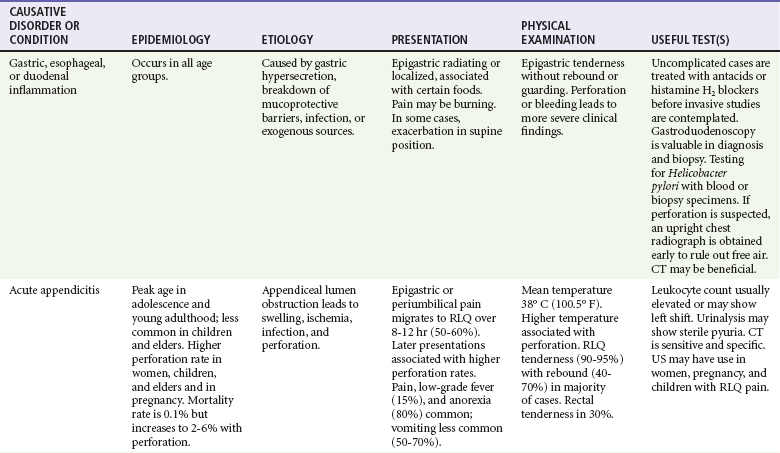

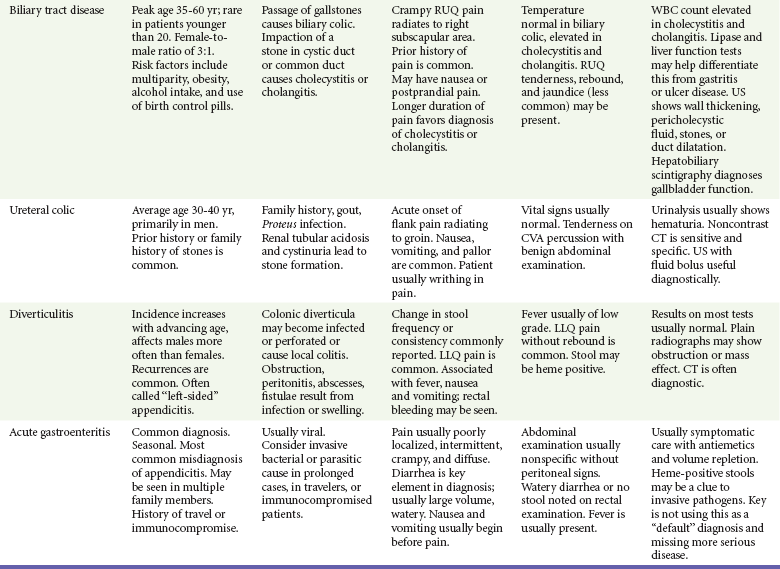

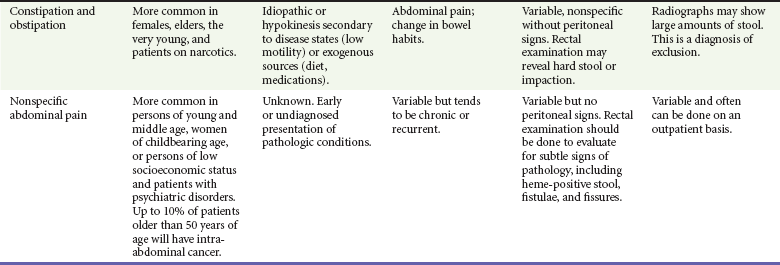

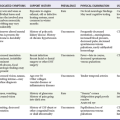

Abdominal pain accounts for up to 10% of all ED visits. Some of the most common causes of acute abdominal pain are listed in Table 27-1. Many patients have pain and other symptoms that are not typical of any specific disease process. Even after ED workup, a diagnosis may not be found in some patients. In addition, several adult groups deserve special consideration: elders (those older than 65 years of age), the immunocompromised, and women of reproductive age.

Increasingly, emergency physicians are seeing patients in immunocompromised states secondary to human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), uncontrolled diabetes, chronic liver disease, chemotherapy, and immunosuppressive drugs. For many reasons, these patients also prove challenging. Their clinical presentation can be misleading owing to atypical physical and laboratory findings, such as lack of fever. The white blood cell (WBC) count, which is unreliable in all cases of abdominal pain, may be frankly misleading in such patients, such as in those with persistent elevations. With regard to infection, the scope of the differential diagnosis also should be broader than usual.1,2 Presentations in the immunocompromised patient may be highly variable and subtle and are discussed in Chapter 183.

Pathophysiology

Pathology in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts remains the most common source of pain perceived in the abdomen. Also, pain can arise from a multitude of other intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal locations (Box 27-1). Abdominal pain is derived from one or more of three distinct pain pathways: visceral, somatic, and referred.

• Foregut structures (stomach, duodenum, liver, and pancreas) are associated with upper abdominal pain.

• Midgut derivatives (small bowel, proximal colon, and appendix) are associated with periumbilical pain.

• Hindgut structures (distal colon and genitourinary tract) are associated with lower abdominal pain.

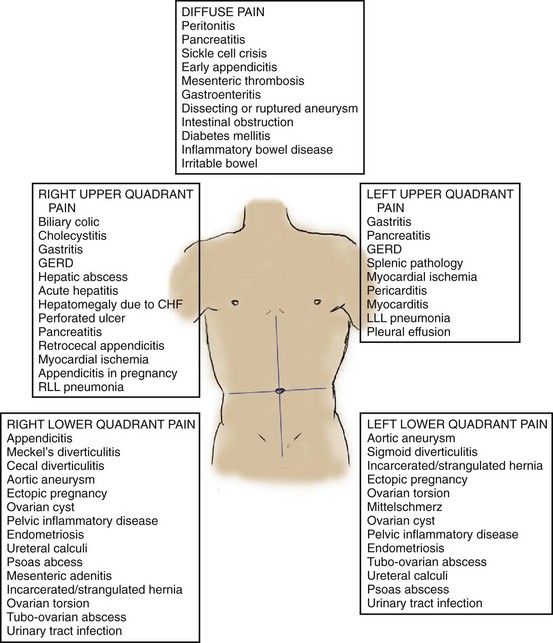

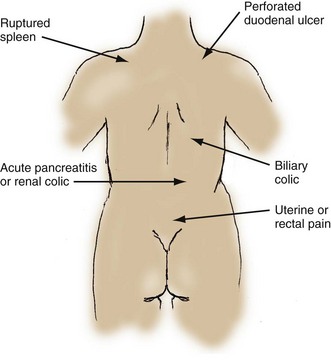

Somatic pain occurs with irritation of the parietal peritoneum. This is usually caused by infection, chemical irritation, or another inflammatory process. Sensations are conducted by the peripheral nerves and are better localized than the visceral pain component. Figure 27-1 illustrates some more typical pain locations corresponding to specific disease entities. Somatic pain is often described as intense and constant. As disease processes evolve to peritoneal irritation with inflammation, better localization of the pain to the area of pathology generally occurs.

Referred pain is defined as pain felt at a distance from its source because peripheral afferent nerve fibers from many internal organs enter the spinal cord through nerve roots that also carry nociceptive fibers from other locations, as illustrated in Figure 27-2. This makes interpretation of the location of noxious stimuli difficult for the brain. Both visceral pain and somatic pain can manifest as referred pain. Two examples of referred pain are the epigastric pain associated with an inferior myocardial infarction and the shoulder pain associated with blood in the peritoneal cavity irritating the diaphragm. It is common for a patient to interpret pain originating from the hips as pelvic pain, especially in the very young or elderly. Lower lobe pneumonias can cause referred abdominal pain secondary to diaphragmatic irritation. Finally, some metabolic disorders and toxidromes may manifest with abdominal pain.

Diagnostic Approach

Differential Considerations

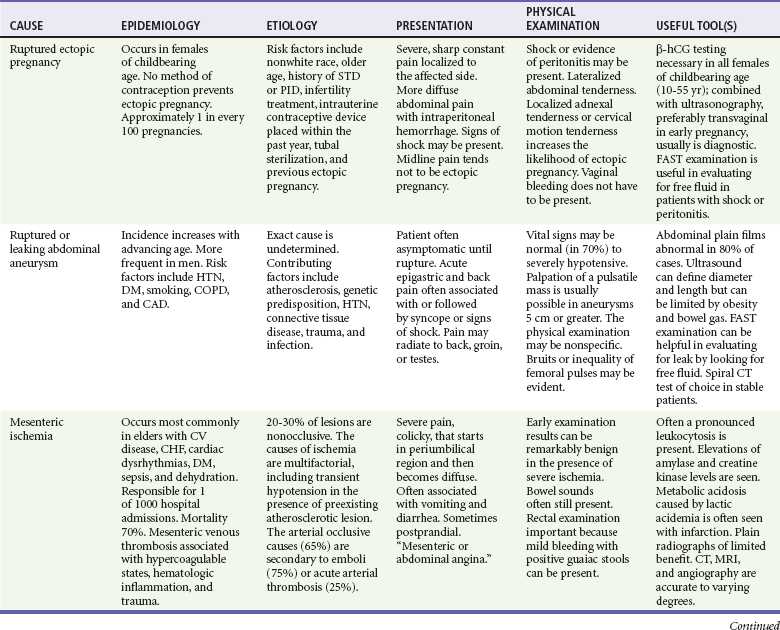

Although significant morbidity and mortality can result from many disorders causing abdominal pain, a few processes warrant careful consideration in the ED. Table 27-2 lists important potentially life-threatening nontraumatic causes of abdominal pain. This group represents the major causative disorders likely to be associated with hemodynamic compromise and for which early therapeutic intervention is critical.

Pivotal Findings

A careful and focused history is central to unlocking the puzzle of abdominal pain. Box 27-2 lists some historical questions with high yields for serious pathology. Language and cultural differences may influence accurate communication and mutual understanding; therefore use of an accurate interpreter can be invaluable.

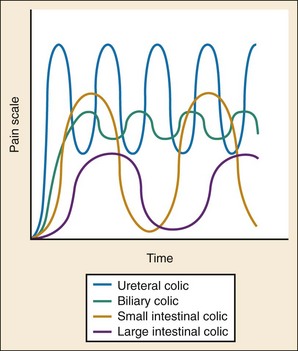

Abrupt onset often is indicative of a more serious cause; however, delayed presentations also may represent a surgical condition. Surgical causes of abdominal pain are more likely to manifest with pain first, followed by nausea and vomiting, rather than with nausea and vomiting followed by pain, although in elder patients the progression may be reversed or pain may be absent entirely. Localization and pain migration also are helpful components of the pain history. Diffuse pain generally is nonsurgical, but it may represent the early visceral component of a surgical process. Colicky pain is indicative of hollow viscus distention, and duration and time of colic may give clues to the identity of the culprit organ, as displayed in Figure 27-3.

Figure 27-3 The characteristics of colicky abdominal pain.

• The diffuse, severe, colicky pain of bowel obstruction

• The “pain out of proportion to examination” observed in patients with mesenteric ischemia

• The radiation of pain from the epigastrium straight through to the midback associated with pancreatitis, either related to primary organ inflammation or secondary to a penetrating ulcer

• The radiation of pain to the left shoulder or independent pain in the left shoulder associated with splenic pathology, diaphragmatic irritation, or free intraperitoneal fluid

• The onset of pain associated with syncope seen in perforation of gastric or duodenal ulcer, ruptured aortic aneurysm, or ruptured ectopic pregnancy

Signs

A thorough abdominal examination is an essential part of evaluation of the patient with abdominal pain. This requires properly positioning the patient supine and exposing the abdomen. The examination should begin with inspection for any signs of trauma, bruising, or skin lesions. The patient should be asked to localize the area of maximal tenderness by pointing with one finger. The abdomen can be divided into four quadrants: right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower; each area is then examined individually. Tenderness in one quadrant often corresponds with the location of the diseased organ, which will direct the workup (see Fig. 27-1). Some disease processes may manifest with pain that is not exclusively within one specific quadrant, such as the suprapubic pain of a urinary tract infection or the midepigastic pain of a gastric ulcer. Although most patients with suspected appendicitis have right lower quadrant abdominal tenderness, a small percentage of patients with proven appendicitis do not.

Ancillary Testing

Liver enzymes and coagulation studies are helpful only in a small subset of patients with suspected liver disease. If pancreatitis is suspected, the most useful diagnostic result is serum lipase elevated to at least double the normal value, because it is more specific and more sensitive than serum amylase for this process. Measurement of serum amylase is of no value if a serum lipase level is available.3 Serum lactate levels are elevated late in bowel ischemia, and such determination may be useful if this entity is suspected, but serum lactate levels cannot be considered either sufficiently sensitive or specific enough to establish or exclude the diagnosis on their own.

Plain radiography of the abdomen has limited usefulness in the evaluation of acute abdominal pain and should be performed only when bowel obstruction or radiopaque foreign body is suspected and there is no intent to obtain a CT scan. For suspected perforated hollow viscus, an upright chest radiograph is a better study than an abdominal film but is not indicated if the plan is to proceed to CT scan regardless of the findings on the plain film. CT of the abdomen has become the imaging modality of choice with nonobstetric, nonbiliary abdominal pain. It allows visualization of both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal structures and has a high degree of accuracy. Incidental findings are common on CT scans and may lead to a diagnosis. CT scan results often lead to a change in diagnosis.4 The proper execution and interpretation of CT studies will reduce morbidity, mortality, and medical expenses.5,6 CT is not indicated for biliary disease, however, for which ultrasound is a much better modality.

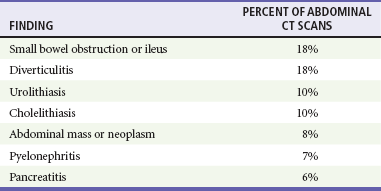

CT has increased diagnostic utility in elderly patients for several reasons. Older people with abdominal pain are significantly more likely to require surgery and have a greatly increased mortality compared with younger adults. Furthermore, evaluation of abdominal pain in elders often is more challenging owing to unreliable findings on physical examination, including vital signs, difficulties in history taking, physiologic age-related changes, and comorbid conditions. In the elderly population, CT results change management or disposition decisions in a significant proportion of patients.7 Table 27-3 lists the most common findings on CT scans in elders with abdominal pain.

Table 27-3

From Hustey FM, et al: The use of abdominal computed tomography in older ED patients with acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med 23:259-265, 2005.

Some controversy surrounds the use of oral contrast in abdominal CT in the critically ill ED patient. Technologic advances have improved image acquisition and resolution, and several studies have shown that intravenous contrast alone may now be adequate in the evaluation of certain suspected pathologic processes, such as solid organ or bowel wall disease.8 CT with intravenous contrast alone also has been shown to be sensitive and specific for the confirmation or exclusion of acute appendicitis.9 The exclusion of oral contrast in these patients significantly decreases ED time to disposition and improves patient satisfaction.

Controversy also surrounds the use of CT with regard to radiation exposure that patients receive. Several studies have attempted to quantify the radiation exposure associated with CT, but in reality there is a wide variation in dosage among different types of CT studies. One study estimated an abdominal CT with intravenous contrast to produce a dose of 10 to 50 millisieverts (mSv), enough to increase the lifetime risk of cancer to 1 in 470 in a 20-year-old woman.10 Another study demonstrated that although patients were more confident when CT imaging was part of their ED workup, they had a very poor understanding of the radiation dose involved.11 CT is an important adjunct in ED care, but the decision to scan is carefully weighed against the patient’s history, physical examination findings, age, and gender. In particular, a patient with a history of chronic undifferentiated abdominal pain, multiple previous CT scans, and alternative diagnoses may benefit from observation as opposed to another CT scan.

• Identification of an intrauterine pregnancy

• Measurement of the cross-sectional diameter of the abdominal aorta to determine the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm

• Detection of free intraperitoneal fluid indicating hemorrhage, pus, or extrusion of gut contents

• Use as a diagnostic aid for detection of the following non–life-threatening conditions:

• Gallstones or a dilated common bile duct, which may be a clue to the presence of choledocholithiasis

• Pericholecystic fluid or gallbladder wall thickening, which may be indicative of cholecystitis

• Free intraperitoneal fluid indicating ascites

• Hydronephrosis indicating possible obstructive uropathy

• Inferior vena cava distention or collapse as an indicator of volume status

Differential Diagnosis

The differential considerations with abdominal pain include a significant number of potentially life- or organ-threatening entities, particularly in the setting of a hemodynamically unstable or toxic-appearing patient. Severely ill patients require timely resuscitation and expeditious evaluation for potentially life-threatening conditions. A focused history and examination should be conducted, and the patient should be placed in a monitored acute care area well equipped for airway control, quick intravenous access, and fluid administration. Only then should appropriate diagnostics be initiated (bedside focused assessment with sonography in trauma [FAST], aorta ultrasound assessment, and radiographic, electrocardiographic, and laboratory studies). This approach is particularly important in dealing with elder or potentially pregnant patients (see Tables 27-1 and 27-2).

Despite the limitations already described, the approach to the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain generally is based on the location of maximum tenderness. Figure 27-1 shows locations of subjective pain and maximal tenderness on palpation related to various underlying causes. In women of childbearing age, a positive result on pregnancy testing may indicate ectopic pregnancy, but the entire spectrum of intra-abdominal conditions remains in the differential diagnosis, as for the nonpregnant patient. When the very broad differential list is compartmentalized by both history and physical examination, ancillary testing should proceed to either confirm or support the clinical suspicion.

Despite the significant variety of tests available, close to one half of the patients in the ED with acute abdominal pain will have no conclusive diagnosis. It is incumbent on the clinician to reconsider the extra-abdominal causes of abdominal pain (see Box 27-1), with special consideration in elders and immunocompromised patients, before arriving at the diagnosis of “nonspecific abdominal pain.”

Empirical Management

There is no evidence to support withholding analgesics from patients with acute abdominal pain to preserve the accuracy of subsequent abdominal examinations; in fact, the preponderance of evidence supports the opposite. Pain relief may facilitate the diagnosis in patients ultimately requiring surgery.12 In the acute setting, analgesia usually is accomplished with intravenously titrated opioids. Meperidine (Demerol) has an unfavorable side effect profile and should be avoided. Intravenous ketorolac, the only parenteral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug available in North America, is useful for both ureteral and biliary colic,13 as well as some gynecologic conditions, but is not indicated for general treatment of undifferentiated abdominal pain. Ketorolac has been shown to cause increased bleeding times in healthy volunteers; it should be avoided in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and potential surgical candidates.14

Aside from analgesics, a variety of other medications may be helpful to patients with abdominal pain. The burning pain caused by gastric acid may be relieved by antacids.15 Intestinal cramping may be diminished with oral anticholinergics, such as the combination agent atropine-scopolamine-hyoscyamine-phenobarbital (Donnatal), although evidence for this is scant and highly variable.

• Unless local antibiotic resistance dictates otherwise, second-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cefamandole, cefotetan, cefoxitin) or quinolone (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) may be combined with metronidazole for the initial dose of antibiotics in the ED. Other noncephalosporin, β-lactam agents with β-lactamase antagonists (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, ticarcillin-clavulanate) are alternatives.

• Many enteric gram-negative bacilli mutate rapidly to produce β-lactamases that are poorly antagonized by specific drug combinations containing clavulanate, sulbactam, or tazobactam. A carbapenem (e.g., imipenem, meropenem) or cefepime is an alternative for patients who may have recently received other antibiotics.

Disposition

• Information gained from the history, physical examination, and test results

• The likelihood of any suspected disease

• Any potential ramifications of progression of a known disease, or of incorrect diagnosis or management

• The likelihood of appropriate and timely follow-up after hospital discharge

• What to do for relief of symptoms or to maximize chances of resolution of the condition (e.g., avoiding exacerbating food or activities, taking medications as prescribed)

• Under what circumstances, with whom, and in what time frame to seek follow-up evaluation, if all goes as desired on the basis of what is known when the patient is in the ED

• Under what conditions to seek more urgent care because of unexpected changes in the condition (such as with natural progression of the process before improvement, incorrect diagnosis made in the ED, or untoward reactions to medications)

References

1. Mönkemüller, KE, Lazenby, AJ, Lee, DH, Loudon, R, Wilcox, CM. Occurrence of gastrointestinal opportunistic disorders in AIDS despite the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:230.

2. Wernck-Silva, AL, Prado, IB. Dyspepsia in HIV-infected patients under highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1712.

3. Pratt, DS, Kaplan, MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1266.

4. Lewis, LM, et al. Quantifying the usefulness of CT in evaluating seniors with abdominal pain. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:290.

5. Federle, MP. CT of the acute (emergency) abdomen. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(Suppl 4):D100.

6. Stromberg, C, Johansson, G, Adolfson, A. Acute abdominal pain: Diagnostic impact of immediate CT scanning. World J Surg. 2007;31:2347.

7. Esses, D, et al. Ability of CT to alter decision making in elderly patients with acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:270.

8. Lee, SY, et al. Prospective comparison of helical CT of the abdomen and pelvis without and with oral contrast in assessing acute abdominal pain in adult emergency department patients. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:150.

9. Mun, S, et al. Rapid diagnosis of acute appendicitis with IV contrast material. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:99.

10. Smith-Bindman, R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Radiology. 2009;169:2078.

11. Baumann, BM, et al. Patient perceptions of computed tomographic imaging and their understanding of radiation risk and exposure. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:1–7.

12. Thomas, SH, et al. Effects of morphine analgesia on diagnostic accuracy in emergency department patients with abdominal pain: A prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:18.

13. Henderson, SO, Swadron, S, Newton, E. Comparison of intravenous ketorolac and meperidine in the treatment of biliary colic. J Emerg Med. 2002;23:237.

14. Singer, AJ, Mynster, CJ, McMahon, BJ. The effect of IM ketorolac tromethamine on bleeding time: A prospective, interventional, controlled study. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:441.

15. Berman, DA, Porter, RS, Graber, M. The GI cocktail is no more effective than plain liquid antacid: A randomized, double blind clinical trial. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:239.