ABDOMINAL PAIN

The causes of abdominal pain are myriad, but may be categorized by classical symptom complexes. As with most disorders, there are serious causes and minor disturbances. The purpose of taking a history and performing a physical examination is to determine the urgency of the situation, in order to plan for evacuation if necessary. Because differentiation between various causes is often difficult, the recommendations that follow are ultraconservative. Any person with severe abdominal pain should be seen by a physician as soon as possible.

GENERAL EVALUATION

1. Nature of the pain. Is the pain sharp (knife-like), aching (constant), colicky (intermittent and severe), or cramping (squeezing)? Has the victim ever suffered a similar episode? Been given a specific diagnosis?

2. Location of the pain. Is the pain well localized to one particular area, or does it radiate to another region (from the back to the groin, for example)? Did the pain begin in one region and move to another?

3. Mode of onset of the pain. Did the pain occur suddenly, or has it gradually increased in intensity? How long has the victim been in pain?

4. Associated symptoms. Is the victim short of breath, nauseated, vomiting, suffering from diarrhea or constipation, or dizzy? Is the victim vomiting blood, bile (green liquid produced by the gallbladder), or “coffee grounds” (blood darkened by stomach acid)? Does the vomit smell like feces?

5. Relief of pain. Is there a position that the victim can assume that will lessen the pain? Does the victim feel better in a quiet position, or is he agitated and constantly moving around?

6. Menstrual history. In the female victim, it is important to determine if there is any chance that the abdominal pain is related to a disorder of pregnancy.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Perform the following physical examination:

1. Observe the victim. Note whether he is active or avoids movement. If possible, note the severity of distress when the victim has his attention diverted (and so is not focusing all of his attention on your examination).

2. Note the victim’s skin color, pulse rate and strength, rate of respirations, effort of breathing, mental status, and temperature. Abnormalities of any of these heighten the possibility of a serious problem.

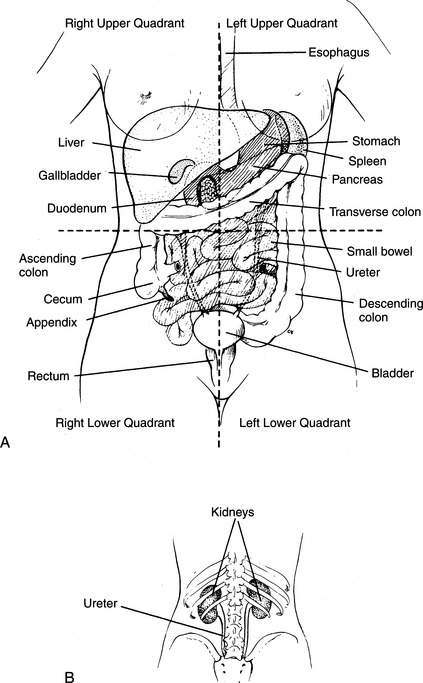

3. Examine the abdomen. This is best done by having the victim lie quietly on his back, with his knees drawn up. Gently press on the abdomen, proceeding from the area of least discomfort to the area of greatest discomfort. For the purposes of examination, the abdomen can be divided by perpendicular lines through the navel into four quadrants: right upper, left upper, right lower, and left lower (Figure 95). The epigastrium is the area of the abdomen directly below (not underneath) the breastbone in the midline. Note where the victim complains of pain and whether the pain is affected by your examination. If the victim has increased sharp pain when you suddenly release your hands from his abdomen after a pressing maneuver, this may indicate “rebound” pain associated with general inflammation of the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis). Rebound pain may be caused by severe infection or leakage of blood or stomach/bowel contents into the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity, or by other problems that are generally quite severe.

When a specific area of the abdomen is tender, there are certain disorders to consider:

Epigastrium. Heart attack, ulcer, gastroenteritis, heartburn, pancreatitis.

Right upper quadrant. Injured liver, hepatitis, gallstones, pneumonia.

Left upper quadrant. Injured spleen, gastroenteritis, pancreatitis, pneumonia.

Right lower quadrant. Appendicitis, kidney stone, ovarian infection (pelvic inflammatory disease), ectopic (fallopian tube [“tubal”]) pregnancy, colitis, bowel obstruction, hernia, miscarriage, kidney stone, painful menses.

Left lower quadrant. Diverticulitis, colitis, kidney stone, ovarian infection, ectopic (fallopian tube [“tubal”]) pregnancy, bowel obstruction, hernia, miscarriage, kidney stone, painful menses.

Lower abdomen (central). Abdominal aortic aneurysm, ovarian infection, ovulation disorder, ectopic (fallopian tube [“tubal”]) pregnancy, bladder infection, colitis, bowel obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease (“irritable bowel”).

Flank. Abdominal aortic aneurysm, kidney stone, kidney infection, pneumonia.

By quadrant, brief descriptions of and treatments for these disorders follow.

EPIGASTRIUM

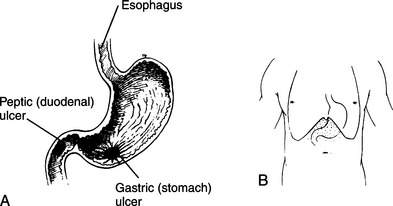

Ulcer (See Also Page 223)

An ulcer is an erosion in the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (peptic ulcer) that penetrates the protective mucous layer and allows acid and digestive juices to erode deeper into the tissues (Figure 96). This causes extreme pain and can lead to bleeding from leaking blood vessels in the ulcer crater. Symptoms include constant burning pain in the epigastrium that is made worse by pressing and is often associated with nausea and/or belching. In a minor case, the pain may be relieved by a meal. In a severe case, when the ulcer has eroded into a blood vessel or has perforated the wall of the stomach or bowel, the victim will vomit red blood or dark brown clotted blood (“coffee grounds”) and complain of pain that may radiate to his back. Rebound tenderness and peritonitis may be present. Dark black tarry bowel movements (melena) are caused by blood that has made its transit through the bowel. Bright red blood or blood clots with a bowel movement can be caused by brisk bleeding from an ulcer, but more commonly originate from bleeding that is occurring within the large intestine (colon) or rectum, or from hemorrhoids (see page 220). Mild bleeding from an ulcer may actually transiently decrease the pain, because blood acts as an antacid. Some ulcers are caused by bacterial (usually, Helicobacter pylori) infection. To eradicate the bacteria and allow the ulcer to heal, a physician must prescribe specific, intense antibiotic therapy.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is often called the “stomach flu” (see the discussion of diarrhea on page 207). Symptoms include waves of crampy upper and/or lower abdominal pain, followed by loose bowel movements. Nausea and vomiting may be present. Occasionally, the victim has symptoms of an upper respiratory infection, with cough, runny nose, sore throat, headache, and fever. The treatment for viral gastroenteritis consists of an adequate liquid diet (hydration is the key to recovery—see page 208) and medicine for intractable vomiting (see page 222). When a victim vomits green bile, this should be taken as a sign that the problem is more serious than straightforward gastroenteritis, although bilious vomiting can occur with repetitive retching, when the stomach has been emptied and duodenal contents are all that is left for regurgitation.

RIGHT UPPER QUADRANT

Injured Liver

If a fall or blow to the abdomen, right flank, or right lower chest is followed by abdominal pain that is worsened by pressing on the right upper quadrant, a torn or bruised liver should be considered. The victim is at risk for severe internal bleeding and should be observed for signs of shock (see page 60). Evacuate him as soon as possible.

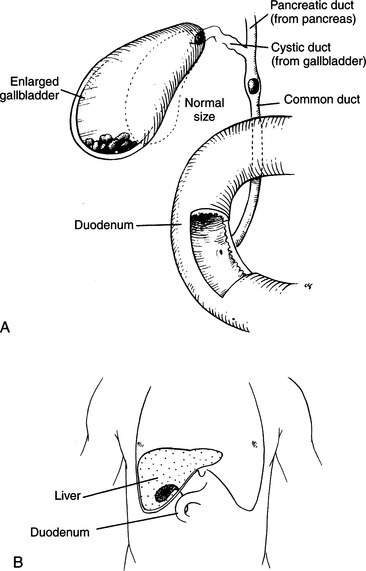

Gallstones (Cholelithiasis)

Gallstones are formed in the gallbladder, which lies under the liver in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The gallbladder stores bile (manufactured in the liver), which is released into the duodenum to aid in digestion following each meal (Figure 97). An attack of gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) occurs when the outlet from the gallbladder or the main bile duct into the duodenum becomes obstructed (usually by a gallstone) and the gallbladder cannot empty. This causes stretching of the gallbladder, inflammation, and painful contraction against an impenetrable passage. There is often an element of infection.

LEFT UPPER QUADRANT

Injured Spleen

If a fall or blow to the abdomen, left flank, or left lower chest is followed by abdominal pain that is worsened by pressing on the left upper quadrant, consider a torn or bruised spleen. The victim is at risk for severe internal bleeding and should be observed for signs of shock (see page 60). Evacuate the victim as soon as possible.

RIGHT LOWER QUADRANT

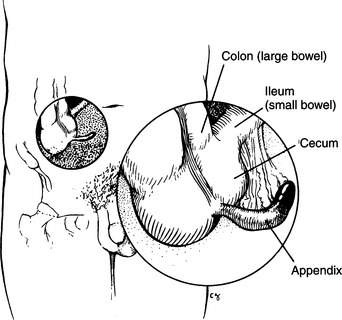

Appendicitis

The appendix is a small (average length 9 cm) sausage-shaped outpouching of the cecum (which is a part of the small bowel), with no modern physiological function, that is located near the transition point where the small bowel becomes the large bowel (colon) (Figure 98). When it becomes obstructed or infected/inflamed (acute appendicitis), the victim typically has a history of crampy pain that begins in the central abdomen (often around the umbilicus), and then moves, over the course of a few hours, to become constant in the right lower quadrant. He may also suffer loss of appetite, constipation or diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and weakness. Pain nearly always precedes any other symptoms. There may be burning on urination if the appendix rests against a ureter carrying urine from the kidney to the bladder. Sometimes, if one presses on the left lower quadrant of a victim of appendicitis, there is pain noted in the right lower quadrant. If an inflamed appendix lies close to the obturator or psoas muscles, there may be pain when the right leg is internally rotated (obturator) or pulled away from the midline (psoas) of the body.

If a woman of childbearing age develops right lower quadrant pain, the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy (see page 133) should always be considered. It is useful to carry a “home” urine pregnancy test kit in the first-aid kit.

Bowel Obstruction

If the intestine becomes obstructed by scar tissue, cancer, injury, or feces, the victim rapidly becomes quite ill. Symptoms include nausea and vomiting, frequently of green bile or feculent (feces-like) material. The victim has waves of cramping pain associated with waves of bowel motion (contractions) that may be visible through the abdominal wall, which is often distended by the dilated loops of bowel. Occasionally, the victim will have small, squirting bowel movements, as a little liquid slips past the obstruction. If a bowel obstruction is suspected, the victim should be immediately evacuated to a hospital.

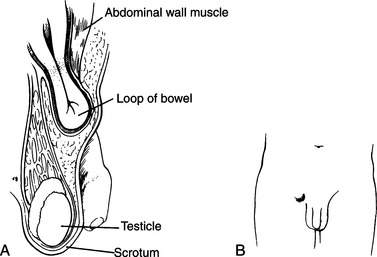

Hernia

If the intestine slips through the muscles of the abdominal wall, usually in the groin or around the umbilicus (navel), a hernia is formed (Figure 99). Symptoms include a visible bulge, abdominal pain, and pain at the site of the hernia. The victim should be made to lie quietly on his back with his knees drawn up; place cold packs directly on the bulge. Give pain medicine to control the discomfort. If sufficient relaxation is obtained, the hernia may slip back through the wall, and the bulge will disappear. Afterward, the victim should wear a support (truss or belt) to prevent recurrence until the problem can be corrected surgically. Straining and heavy lifting should be avoided.

If the intestine will not slip back through, the hernia is trapped (incarcerated). This is an emergency, because if the blood supply to the bowel is pinched off, the tissue can be severely damaged or die, and/or a bowel obstruction (see page 127) can be created. An incarcerated hernia is extremely painful, and if the bowel is injured, the overlying skin frequently becomes reddened or dusky in appearance. Because the aforementioned maneuvers for reduction of a hernia will not be successful and pain will increase, the victim should be rapidly evacuated to a hospital.

LEFT LOWER QUADRANT

Diverticulitis

Diverticula are small outpouchings that develop at weak points along the wall of the colon (large bowel), probably because of high pressures associated with muscle contractions during the passage of stool. When these sacs become obstructed and/or inflamed (most frequently in middle-aged or elderly individuals), they enlarge and create pain and fever. Usually, the left lower quadrant is involved, because diverticula tend to form in the left-side portion of the colon (descending colon) more frequently than in the right-side portion (ascending colon) or horizontal connecting section (transverse colon). A ruptured diverticulum can cause a clinical picture much like that of a ruptured appendix (see page 126), with pain in the left side of the abdomen instead of the right side. The victim should seek medical attention, and his diet should be limited to clear fluids. Antibiotics (metronidazole, metronidazole combined with doxycycline, amoxicillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cefixime, ciprofloxacin, or cefpodoxime) should be administered if help is more than 24 hours away.

LOWER ABDOMEN (CENTRAL)

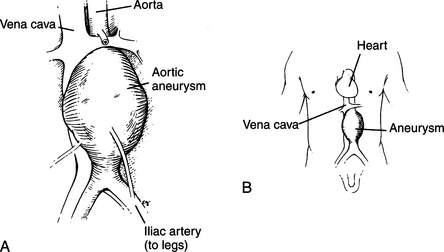

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

An aneurysm is a dilated blood vessel that has been weakened by the ravages of age, high blood pressure, and atherosclerosis (Figure 100). At a certain point, the wear and tear become too much and the blood vessel rips, causing either a slow leak or rapid, massive bleeding that leads to sudden collapse and death. This generally occurs spontaneously only in the elderly, unless there is a congenital defect; traumatic tears of the aorta occur in all age groups.

Any elderly person who suddenly develops abdominal pain or back pain associated with weakness, a fainting spell, decreased sensation and/or abnormal color in the legs or feet (even if transient) or shortness of breath should be immediately rushed to a hospital. In the best of circumstances, this is a highly critical situation. Be prepared to treat the victim for shock (see page 60).

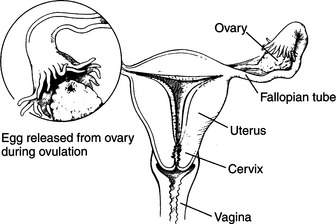

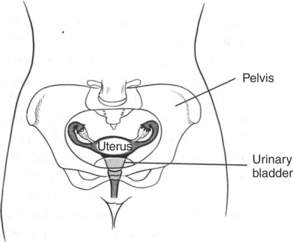

Ovarian Infection

The ovaries and fallopian tubes (Figures 101 and 102), which carry eggs from the ovaries to the uterus, may become infected, commonly with the bacteria that cause gonorrhea (a form of venereal disease) or by other infectious agents, such as Chlamydia trachomatis. Symptoms include abdominal pain in the lower quadrants (greatest on the side of the affected ovary), fever, shaking, chills, nausea, vomiting, and weakness. Occasionally, the victim will complain of a yellow-greenish vaginal discharge. If you suspect an infection, take the victim to a hospital immediately. If more than 24 hours will pass before a doctor can be reached, the victim should be started on tetracycline 500 mg four times a day, amoxicillin-clavulanate 500 mg 2 to 3 times per day, or doxycycline 100 mg two times a day, for 14 days (doxycycline and tetracycline are effective against Chlamydia). Azithromycin 1 g in a single dose is also effective against chlamydial infection. If you suspect gonorrhea, administer cefixime 400 mg orally twice a day (for single-dose therapies for gonorrhea, see page 299). To treat gonorrhea and chlamydial infection at the same time (the two germs often “travel” together), administer azithromycin in a 2 g single dose (again, see page 299). If the victim is pregnant or allergic to penicillin and gonorrhea is suspected, administer azithromycin 2 g in a single dose or erythromycin base 250 mg four times a day for 14 days. Another treatment regimen that may be used is ofloxacin 400 mg twice a day or levofloxacin 500 mg once a twice for 14 days, either of these with the addition of metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 14 days, noting that this regimen may be less effective than the others noted because of bacterial resistance to fluoroquinolone drugs.

Ovulation, Ovarian Cyst, and Torsed (Twisted) Ovary

Some women suffer sudden, intense abdominal pain at the time of ovulation (when the egg is released from the ovary) (see Figure 101). This is caused by a small amount of blood and ovarian fluid, which irritates the lining of the abdomen. Symptoms include pain that suddenly develops in the right or left lower quadrant, and is worsened by movement or deep palpation of the area. Treatment is pain medicine and rest. A ruptured ovarian cyst (which releases tissue fluid or blood) or torsed (twisted) ovary causes similar but much more severe symptoms, which may include excruciating pain, nausea and vomiting, and a rigid (to the pressing hand) abdomen. Any of these conditions may be difficult to distinguish from appendicitis (see page 126) if the right ovary is involved. Treatment for a torsed ovary may require surgery. Any sudden abdominal discomfort in a woman of childbearing age should be promptly evaluated by a physician.

Bleeding from the Vagina

If abnormal (in amount or character) pain and/or bleeding occurs during or between menstrual periods, the cause should be determined by a physician. Until the evaluation is performed, exertion should be kept to a minimum. If periods have been missed (or if the victim is known to be pregnant) and copious vaginal bleeding develops, place the victim at rest and transport her rapidly—by litter, if possible—to a physician. If the bleeding is spotty, the victim may walk with assistance. A ruptured tubal (ectopic) pregnancy can rapidly become life threatening. In this situation, a pregnancy situated in a fallopian tube (rather than in the uterus) causes the tube to rupture. The symptoms include vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain (which can become severe), and signs of shock (see page 60). This is a true medical emergency.

Vaginitis, Vaginal Discharge, and Vaginal Infections

Bacterial vaginosis is caused by a shift in vaginal bacterial flora from lactobacilli-dominant to mixed flora, and is characterized by a milky (white or gray), sticky, homogeneous, and sometimes thin discharge with an abnormal (“fishy,” particularly after intercourse) odor, as well as occasional itching and pain. It is definitively diagnosed by measuring the vaginal pH at a value greater than 4.5 and noting a specific type of cell (“clue cell”) when the discharge is examined with a microscope. Treatment is either metronidazole 500 mg by mouth twice a day for 7 days or 0.5% or 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel (such as MetroGel-Vaginal) once a day for 5 days; or clindamycin phosphate 300 mg by mouth twice a day or 1 applicator (5 g) of 2% vaginal cream at bedtime for 7 consecutive nights; or 2% extended-release clindamycin cream, one application intravaginally.

For first episode of genital herpes (take medication by mouth for 7 to 10 days): acyclovir 200 mg 5 times a day or 400 mg 3 times a day; or valacyclovir 1 g twice a day; or famciclovir 250 mg 3 times a day.

For recurrent episode of genital herpes (take medication by mouth for 5 days): acyclovir 200 mg 5 times a day or 800 mg twice a day; or valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily or 1 g once a day; or famciclovir 125 mg twice a day.

For suppressive therapy against genital herpes (take medication twice a day for as long as suppression is desired: acyclovir 400 mg; or valacyclovir 500 mg; or famciclovir 250 mg. It is possible that taking any of these medications once a day, rather than twice a day, may be effective.

Emergency Contraception

In the event that emergency contraception is desired (e.g., for unprotected sexual intercourse or contraceptive failure), levonorgestrel tablets 0.75 mg (Plan B) are available over-the-counter and approved for women age 18 years and older. A prescription is required for a woman age 17 years or younger. This medication does not protect against infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted diseases. The medication provides a short burst of hormones that affects the lining of the uterus and alters sperm transport, which prevents sperm from meeting the egg to achieve fertilization. Levonorgestrel is effective if given within 5 days (120 hours) of intercourse, but is most effective if given within the first 24 hours after intercourse. The dose is one pill by mouth, followed by a second pill 12 hours after the initial pill.

FLANK

Kidney Stone

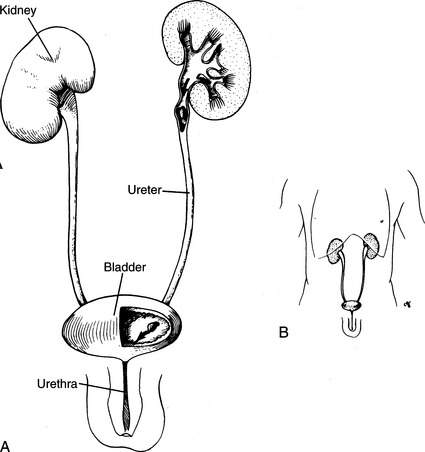

A “kidney stone” originates in the urine-collecting system of the kidney, and most commonly causes pain when it travels down the ureter (ureteral stone) to the bladder (Figure 103). After traversing the bladder, it may enter the urethra and continue to wreak havoc. The most common compositions of stones are calcium-derived (80%), struvite (15% to 20%; magnesium ammonium phosphate), uric acid (5% to 10%), and cysteine (less than 1%).

The pain of a kidney stone is usually sudden in onset and often becomes intolerable. The location of the pain is related to the location of the stone. If the stone is high in the ureter, the pain localizes to the victim’s back (on the affected side), with some radiation to the abdomen. Lightly tapping over the flank and lower ribs on the back of a victim with a kidney stone will often cause extreme pain. If the stone is passing through the lower ureter, the victim will have extreme pain in the back, abdomen, and genitals. When the stone is not moving, the pain (renal “colic”) may disappear as quickly as it began. A small (less than or equal to 2 mm in diameter) stone may take 7 to 10 days to pass; a 2 to 4 mm stone may take up to 2 weeks; and a stone larger than 4 mm may take up to 3 weeks.

If the diagnosis of a kidney stone appears relatively certain, give the victim the strongest pain medicine that is necessary and available, and encourage him to drink copious amounts of fluid. Ketorolac (10 mg by mouth every 4 to 6 hours, not to exceed 5 days) has been recommended as a pain medication for kidney stone because it may decrease spasm in the ureter; it may be given along with a narcotic drug, such as hydrocodone, to enhance the analgesic effect. Another useful drug if ketorolac is not available is diclofenac 50 mg by mouth 2 or 3 times a day. Some urologists recommend adding tasmulosin (Flomax) 0.4 mg by mouth once a day for a few days after the onset of pain associated with passing a kidney (ureteral) stone. Seek physician evaluation as soon as possible. If the victim is elderly, consider the diagnosis of ruptured aortic aneurysm (see page 130). If you have any suspicion that the victim might have an aneurysm, evacuate him immediately.