Abdominal Incisions

Before performing an incision in the abdominal wall, the gynecologic surgeon should have anticipated the type(s) of surgical procedure that will be done and possible complicating aspects associated with the operation. Consideration should be given to how far cephalad from the pelvis the operative exposure will need to be. Additionally, the surgeon should weigh the cosmetic desire(s) of the patient, the urgency of the surgery, the patient’s history of previous laparotomies, and the risk of postoperative wound dehiscence.

Knowledge of pelvic anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall is essential to avoid or secure major vessels, to enhance appropriate repair so as to reduce the risk of incisional hernia or wound dehiscence, and to facilitate smooth entry. Practically, incisions may be categorized as midline or transverse. Transverse incisions may be further subdivided into muscle-splitting and muscle-cutting varieties.

Transverse Incisions

Maylard Incision

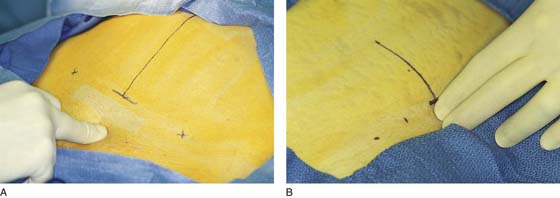

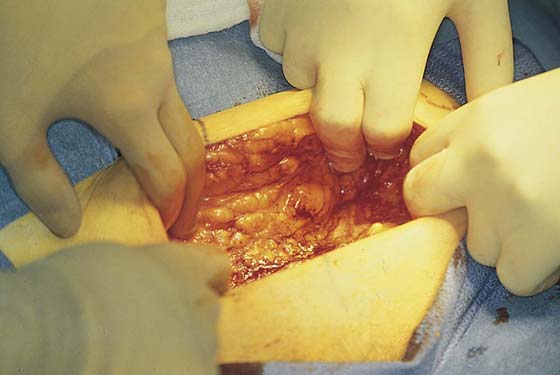

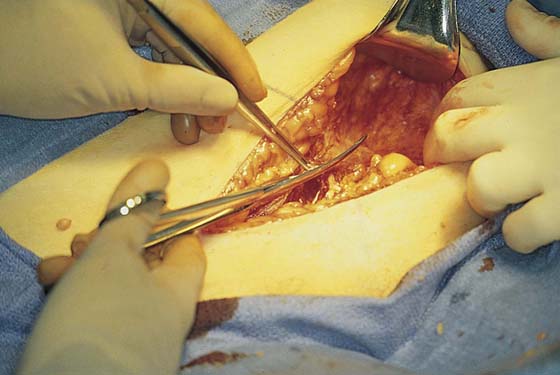

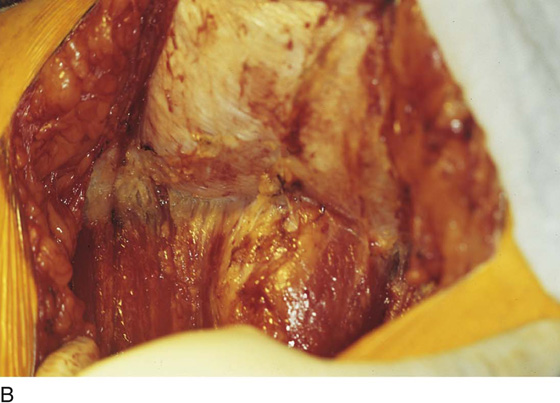

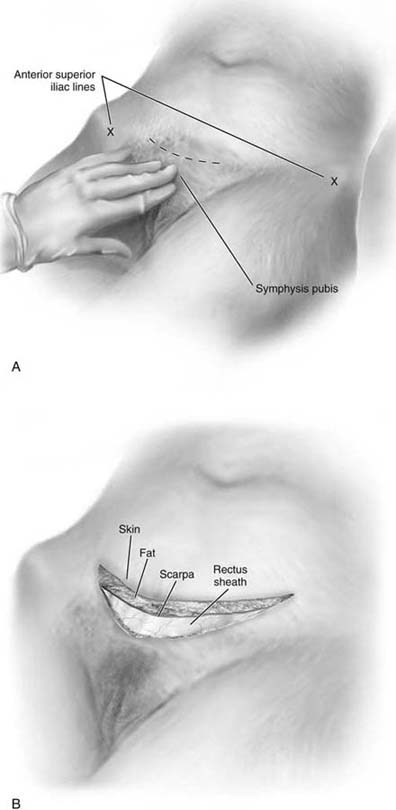

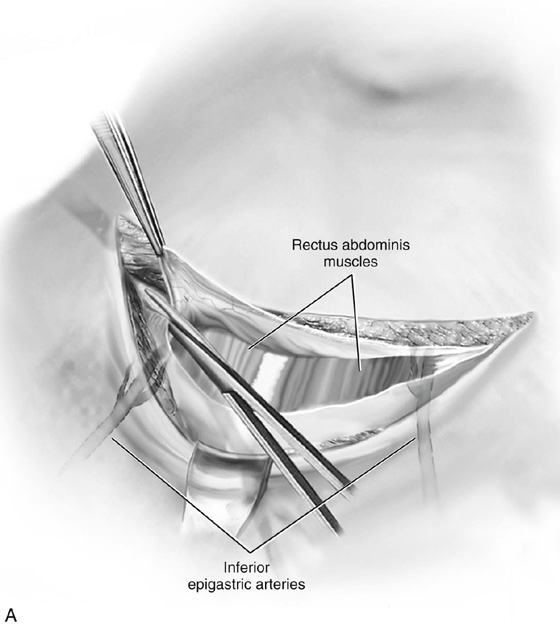

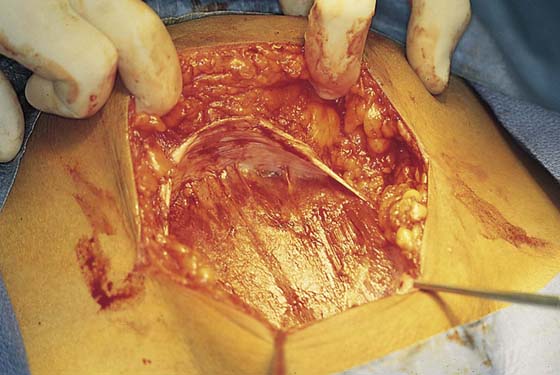

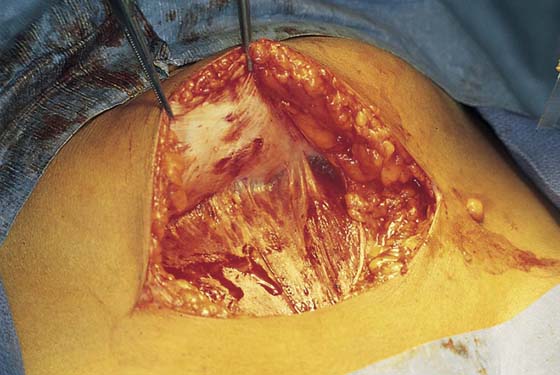

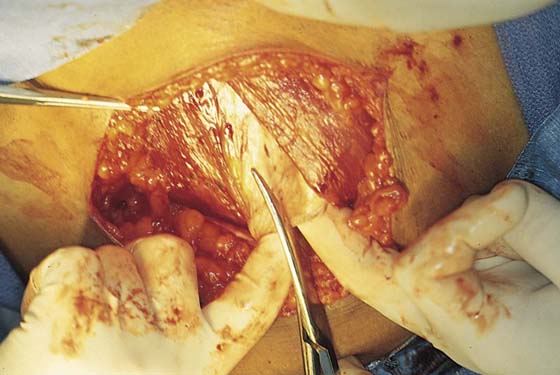

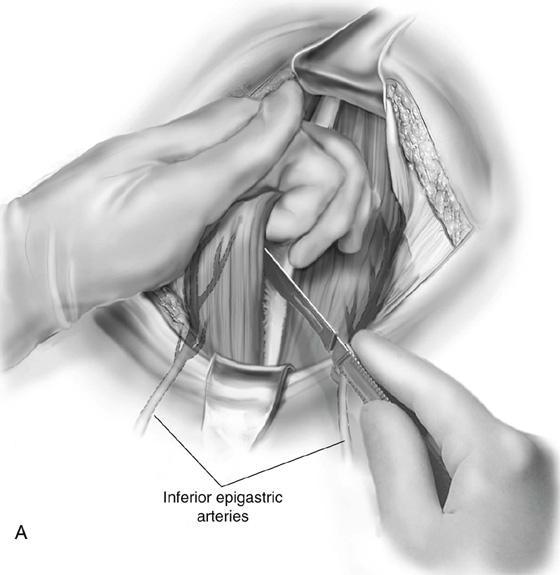

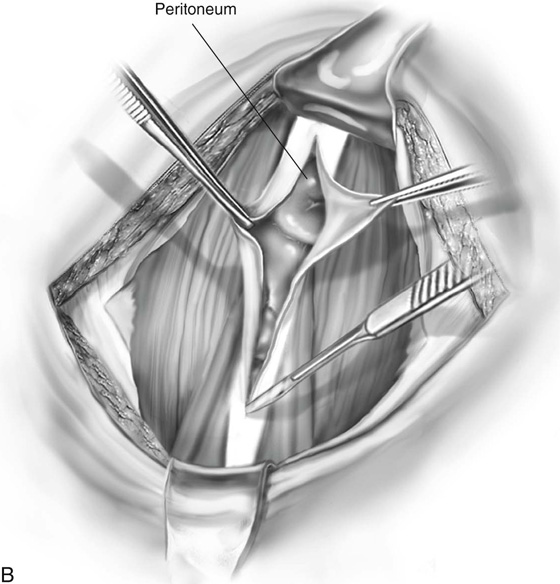

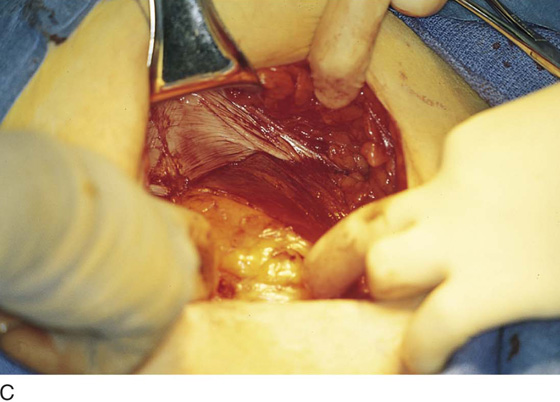

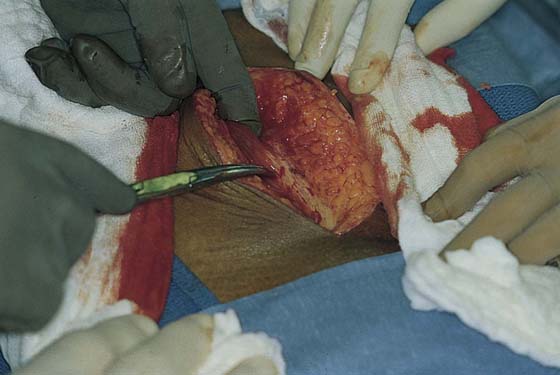

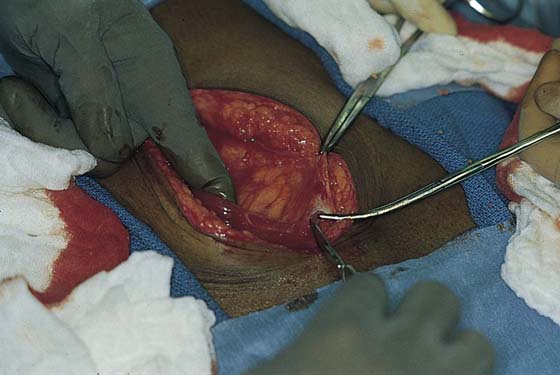

The Maylard incision is made two fingerbreadths above the symphysis pubis (i.e., approximately 3–4 cm) (Fig. 8–1A, B). It is carried down through the subcutaneous fat and through Scarpa’s fascia (Fig. 8–2). The fascia overlying the abdominal wall muscles is identified (Fig. 8–3). Scarpa’s fascia covers the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscles and the aponeurosis of the external oblique. The operator should, of course, be familiar with the course of the inferior epigastric vessels, which lie on the transversalis fascia. After taking their origin deeply at the lowest portion of the external iliac artery and vein, the inferior epigastric vessels range anteriorly, cephalad, and medially to cross the lower abdominal wall and locate alongside the rectus abdominis muscles. The fascia overlying the rectus abdominis muscles is cut transversely, and the incision is continued laterally to include a greater or lesser portion of the external oblique aponeurosis (depending on the planned width of the incision) (Fig. 8–4). Next, the fascia is cut in the midline between the two recti (Fig. 8–5A–C). The operator inserts one or two fingers under the rectus muscle from the midline to the right or left, depending on which muscle is to be cut first. The finger(s) emerges from the lateral border under the rectus muscle above the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 8–6). The muscle is carefully cut over the operator’s finger(s) or a sterile tongue blade (Fig. 8–7). A similar procedure is carried out on the opposite side (Fig. 8–8A). If the incision is to be extended, the inferior epigastric vessels are isolated, doubly clamped, cut, and suture ligated with 3-0 Vicryl or 2-0 silk. Finally, the peritoneum is elevated, incised, and opened along the length of the incision transversely (Fig. 8–8B).

FIGURE 8–1 A. The midline is marked with a solid vertical line. B. The Maylard incision is made 4 cm (two fingerbreadths) above the superior margin of the pubic symphysis, indicated by the dotted line.

FIGURE 8–2 The transverse incision is carried deep through the thick fat to Scarpa’s fascia.

FIGURE 8–3 The underlying fascia of the rectus sheath is visible at the depth of the incision.

FIGURE 8–4 The fascia of the anterior rectus sheath is incised transversely with curved Mayo scissors.

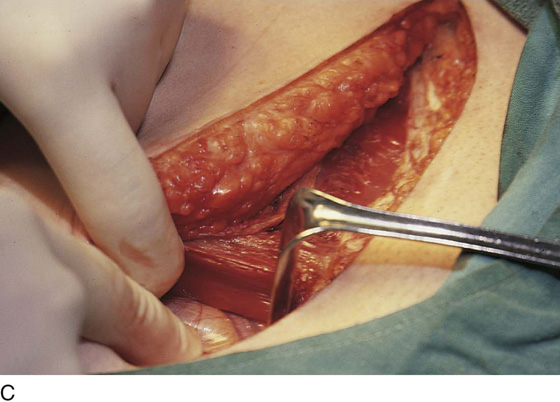

FIGURE 8–5 A. The rectus muscle is now clearly in view. B. The lower portion of the rectus fascia (sheath) is dissected from the muscle belly. C. The inferior epigastric vessels are identified.

FIGURE 8–6 The linea alba has been incised, and the fingers of the operator’s hand bluntly dissect the muscle from the posterior sheath/peritoneum.

FIGURE 8–7 The belly of the rectus sheath is isolated before it is cut.

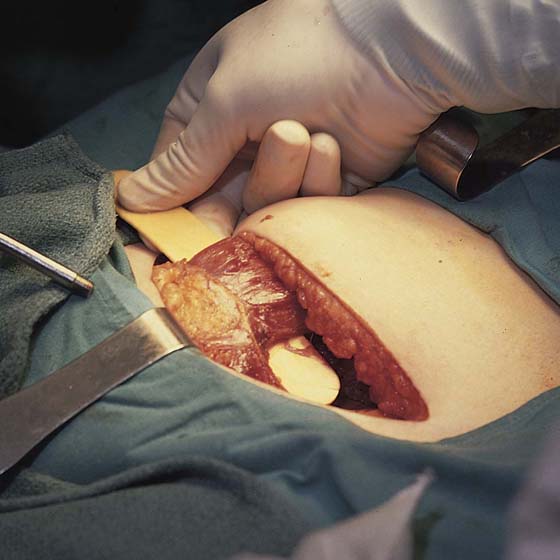

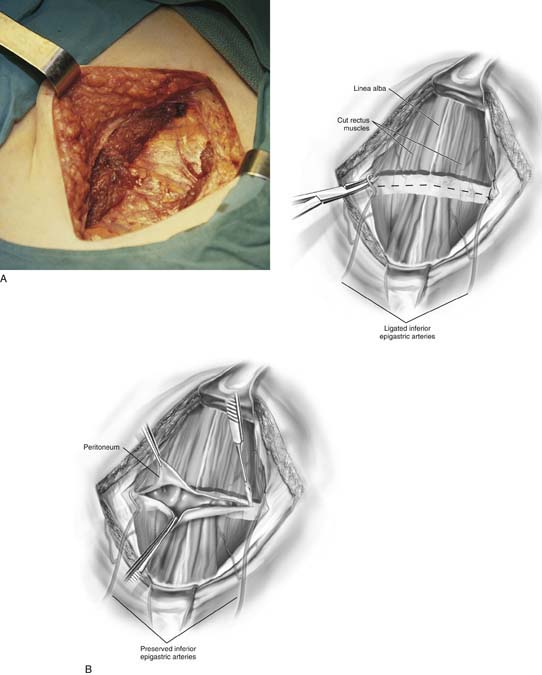

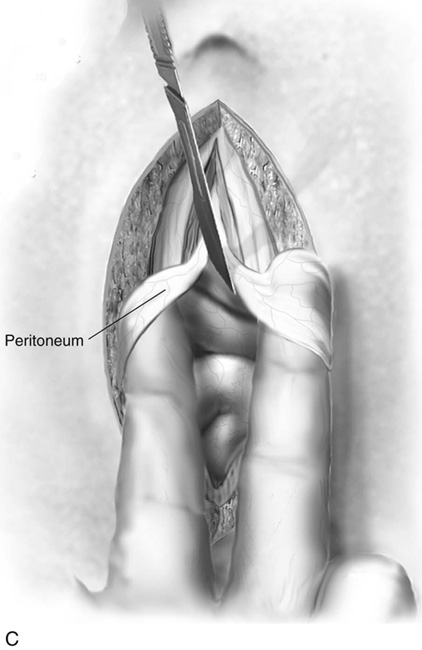

FIGURE 8–8 A. The rectus muscles have been fully divided. Note how dry the field and muscles are even in the absence of any ligatures. B. The schematic view (upper figure) shows the isolation and division of the inferior epigastric vessels and the transverse sectioning of the rectus muscles. The lower figure shows the incision through the peritoneum (in this case preserving the inferior epigastric vessels).

Pfannenstiel Incision

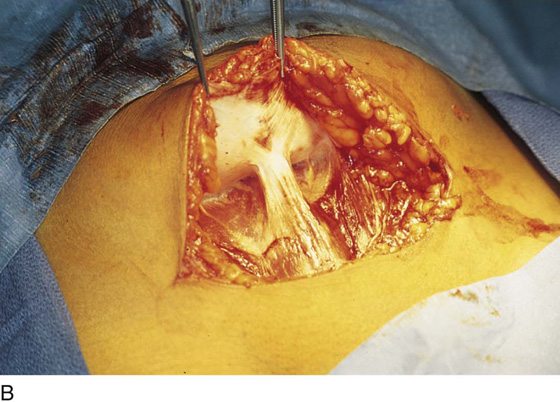

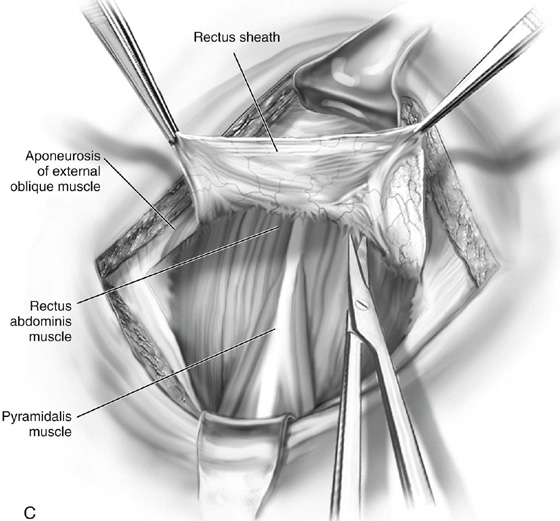

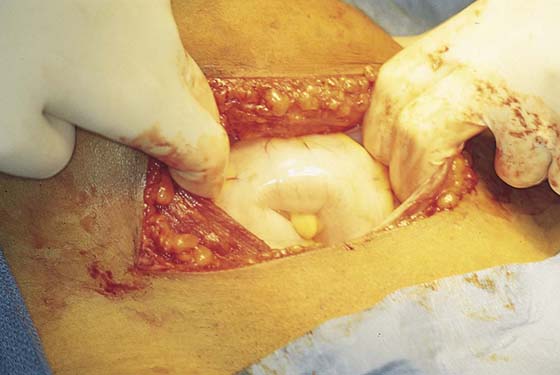

This incision is made transversely in a manner similar to the Maylard incision, although some surgeons may prefer to curve the incision upward toward the anterior superior iliac spine to gain more exposure (the “smile” incision) (Fig. 8–9A, B). The cut traverses the skin, the fat, Scarpa’s fascia, and the rectus sheath (i.e., to the lateral margin of the rectus sheath). Typically, the incision through the fascia is superficial and therefore is unlikely to impinge on the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 8–10A). The sheath is clamped and elevated to allow dissection of the sheath cranially and to free it from the underlying rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 8–10B, C). This plane can be accentuated by the operator’s spread fingers, creating countertraction via pressure on the rectus muscles (Fig. 8–11). The dissection is continued upward for several centimeters (Fig. 8–12) and may be continued to the level of the umbilicus (Fig. 8–13). The rectus muscles are separated vertically in the midline, and the peritoneum is entered. The properitoneum and peritoneum are opened together vertically in the midline (Fig. 8–14). The pyramidalis muscles are similarly cut in the midline down to the level of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 8–15A–C). The peritoneum is carefully dissected inferiorly to the level of the bladder reflection (Fig. 8–16).

Cherney Incision

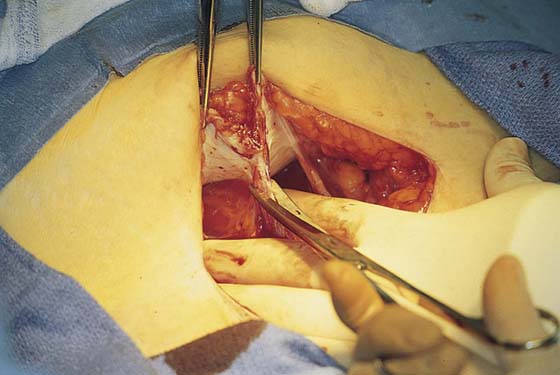

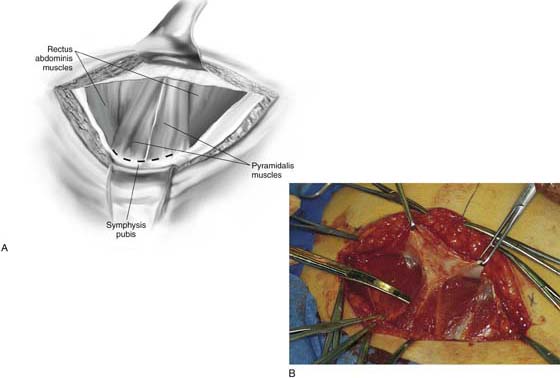

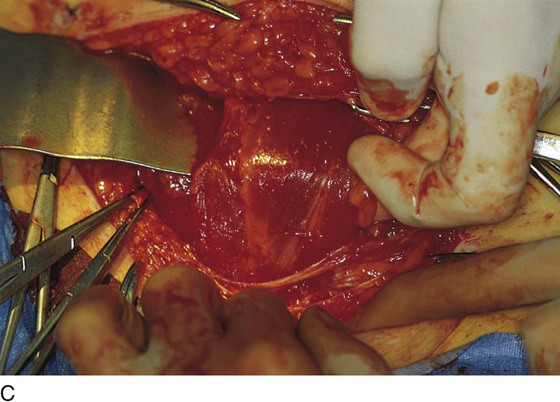

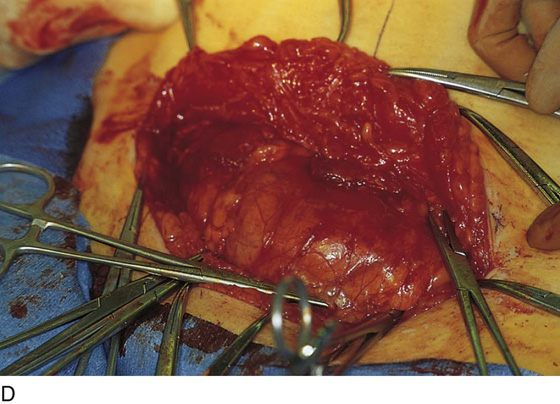

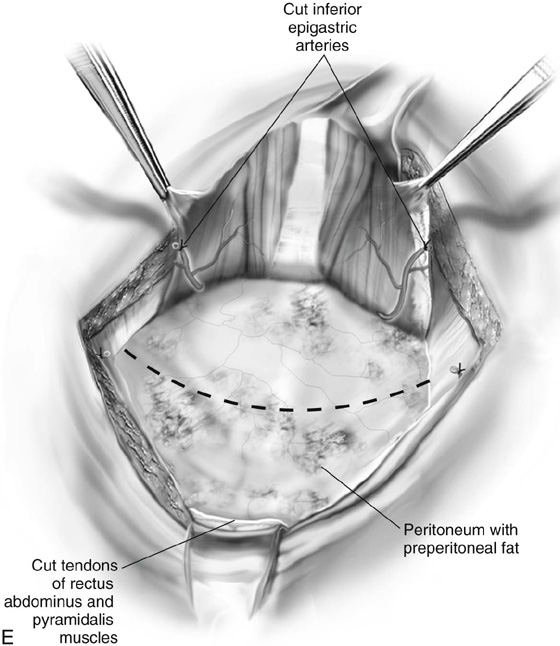

This incision is made approximately 1cm lower than the Maylard incision. The incision is carried through the skin, fat, subcutaneous tissue, and Scarpa’s fascia. The rectus sheath is opened transversely. The rectus muscles are divided transversely from their insertion onto the symphysis pubis. The incision may now be extended laterally through the aponeurosis of the external oblique by isolating, ligating, and cutting the inferior epigastric vessels. The rectus muscles may likewise be freed upward to enhance the space for surgical exposure (Fig. 8–17A–E).

Kustner Incision

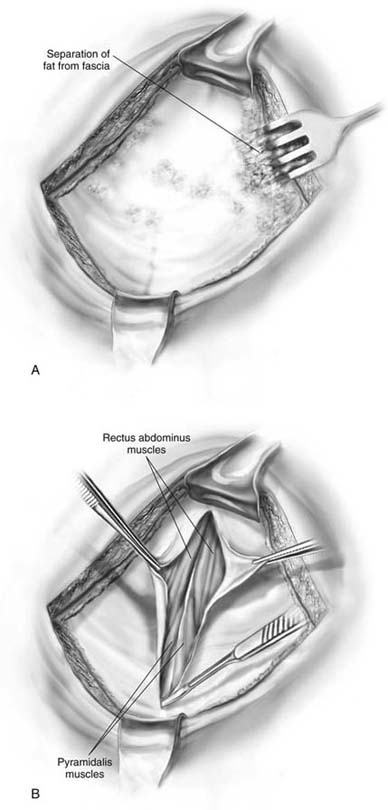

This hybrid incision is a transverse incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue only (i.e., it is used for cosmetic rather than structural reasons). From this point on the exposure is identical to that of a vertical incision. The fascia is opened in the midline, along the linea alba. The rectus muscles are separated vertically by sharp dissection. The pyramidalis muscles are cut. The peritoneum is entered and opened vertically in the midline (Fig. 8–18A, B).

FIGURE 8–9 A. Preparation is made for the curvilinear Pfannenstiel incision (smile incision) at the level of the pubic hair line. B. The incision is carried down through the skin, fat, and Scarpa’s fascia to the fascia overlying the rectus sheath.

FIGURE 8–10 A. The rectus fascia is incised, with care taken to avoid injuring the underlying inferior epigastric vessels. B and C. The cranial (upper) flap of the fascia is sharply dissected upward, exposing the underlying rectus muscles.

FIGURE 8–11 Scissors are needed to cut the rectus sheath in the midline, whereas the sheath on either side can be easily dissected with the operator’s fingers.

FIGURE 8–12 The sheath is freed both cranially and caudally.

FIGURE 8–13 The linea alba is clearly exposed for a distance of 8 cm.

FIGURE 8–14 The peritoneum is entered and opened by a midline incision.

FIGURE 8–15 A. The rectus muscles are sharply separated from each other before the incision is made into the peritoneum, as shown in Figure 8–14. B. The peritoneum may be opened vertically with scissors or a scalpel. C. The omentum is clearly visible underlying the peritoneum.

FIGURE 8–16 The underlying small intestine fills the wound as the omentum is pushed away.

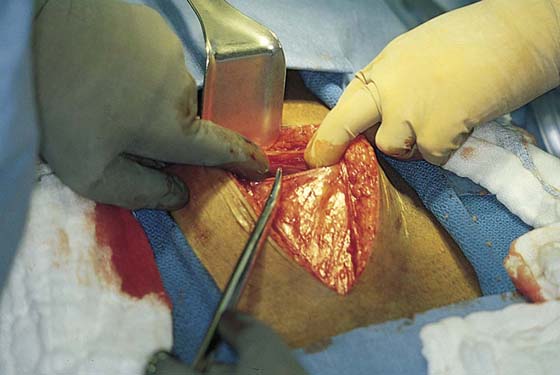

FIGURE 8–17 A. The Cherney incision is made immediately above the symphysis pubis and is carried down to the rectus sheath, which is opened transversely. The inferior epigastric vessels are sectioned and the insertion of the muscle(s) onto the pubic bone is separated and reflected upward (cranially). The peritoneum is incised laterally, thereby creating excellent exposure of the abdominal cavity and pelvis. B. The rectus sheath has been opened transversely. The Allis clamps hold the cranial portion of the sheath. The scissors point to the pyramidalis muscle. C. The rectus muscle (left) has been dissected from the underlying fascia. The operator’s finger is at the lateral margin. The assistant’s hand marks the attachment of the muscle to the symphysis pubis. D. The muscles have been cut free from the symphysis pubis. Note the excellent and wide exposure. E. The transversus fascia/peritoneum is widely exposed and may be opened transversely (dashed line) to provide excellent pelvic exposure. (See previous page for illustration.)

FIGURE 8–18 A. The skin and fat have been opened transversely. The dissection now extends vertically to separate the fascia overlying the muscles from the fatty tissue. B. The rectus sheath is opened vertically in the midline. The posterior rectus sheath and the peritoneum will be likewise cut in the midline.

Midline Incision

The midline incision is commonly used for lower abdominal operative procedures in obstetric, gynecologic, and general surgery cases. For emergencies it has the advantages of offering the most rapid entry and the least amount of incisional bleeding. The greatest deficiency of the midline incision is its diminished postoperative tensile strength compared with that of transverse fascial incisions. Therefore, a greater propensity is observed for wound dehiscence as well as ventral hernias with the midline vertical approach. Specific closure techniques have been designed principally to decrease the risk of dehiscence with midline incisions.

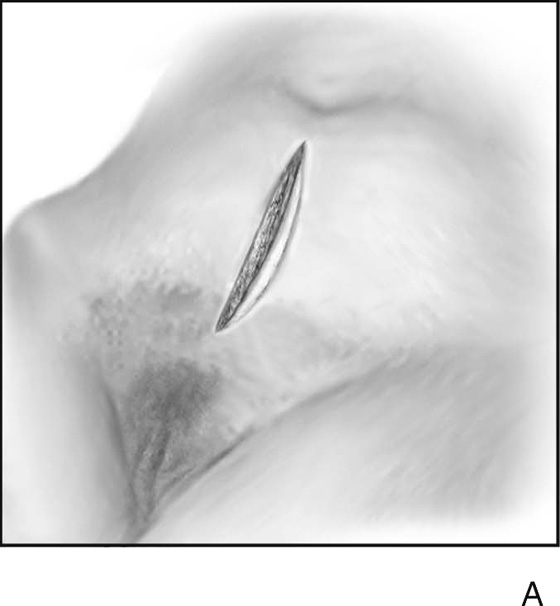

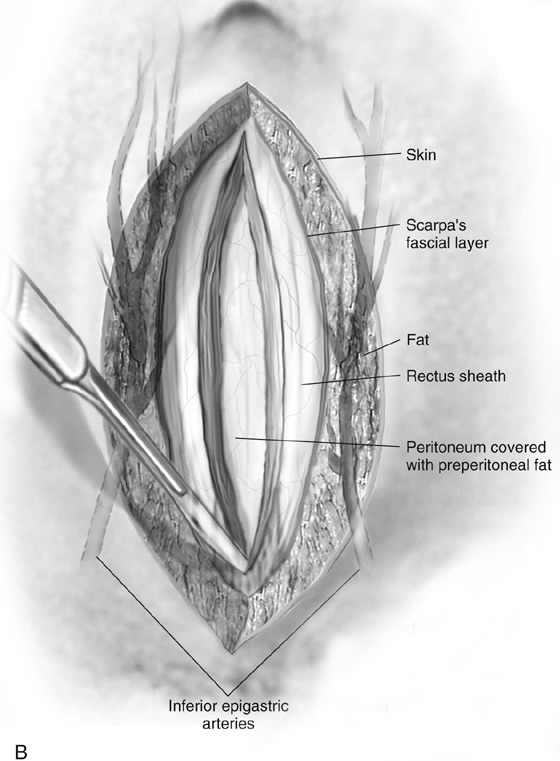

The incision starts at the level of the umbilicus and is carried as a straight line to the symphysis pubis (Fig. 8–19). Although Howard Kelly was said to have routinely opened the belly via a single vertical cut through all the layers of the abdominal wall, this method is not recommended by the authors of this book. The initial cut is, however, typically carried down through the skin, subcutaneous fat, and Scarpa’s fascia (Fig. 8–20). Next, the rectus sheath is opened vertically along the entire length of the incision (Fig. 8–21). The right and left rectus muscles are identified and, by means of sharp and blunt dissection, the muscles are separated in the midline caudad to the level of the pyramidalis muscles (Fig. 8–22). The pyramidalis muscles are cut with Mayo scissors or a scalpel in the midline down to the upper edge of the symphysis pubis.

Next the properitoneal fat is pushed to the right or left at the upper level of the incision between the rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 8–23A–C). The peritoneum is grasped with two forceps or two clamps and elevated. A sharp knife incision opens into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 8–23C). Using a Metzenbaum scissors or Mayo scissors, the peritoneum is opened for the length of the incision over the operator’s index and center fingers or a wide malleable retractor (Fig. 8–24) so as to protect the underlying intestine from injury. The lower portion of the incision should be opened with great care to avoid injury to the urinary bladder. Typically, the fatty tissue around the bladder demonstrates significantly greater vascularity when compared with the midline peritoneum and fat.

FIGURE 8–19 The linea nigra is clearly shown in this patient and is an excellent reference point for initiating a vertical incision.

FIGURE 8–20 The midline incision is carried down to the level of the rectus sheath.

FIGURE 8–21 The fat is sharply dissected from the silvery gray sheath.

FIGURE 8–22 The sheath has been opened and the two rectus abdominis muscles are separated from each other.

FIGURE 8–23 A. Schema for the vertical midline incision. The cut is made below the umbilicus and is carried caudad to the upper margin of the symphysis pubis. B. The underlying posterior sheath and the peritoneum are brought into view between the separated rectus muscles (middle). C. The peritoneum is opened in the midline sharply, with care taken to shield the underlying intestines from injury (lower).

FIGURE 8–24 The peritoneum is entered at the upper extremity of the incision and is “tented-up” to allow safe incision (i.e., well away from the underlying intestine).