26 Abdominal incidentalomas

Case

Mrs AI, a slim, previously well 65-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner with dysuria. There was a trace of blood in her urine and erythrocytes were seen on urine microscopy, so a renal ultrasound scan was carried out. This did not detect any renal abnormality, but did reveal a 1-cm solitary, mobile gallstone in an otherwise normal, thin-walled gallbladder. A complete ultrasound scan assessment of the liver, biliary tree and pancreas was carried out and no other pathology was identified; in particular, there was no evidence of choledocholithiasis. Following first principles, her doctor first of all revisited her medical history and found no symptoms other than the dysuria and in particular no biliary symptoms. No abnormality was detected on physical examination, in particular no biliary signs. Her liver function tests were normal.

Diagnosis and Management

In women, unexpected pelvic mass lesions are common. However, these are not covered here. Dystrophic calcification (normal serum calcium, abnormal tissue) is a very common incidental finding on abdominal imaging. Dystrophic calcification is often seen in malignancies but is most commonly due to age-related degeneration or inflammation and scarring and will not be treated as an incidental mass in the context of this chapter.

The investigation plan

The investigation of incidentalomas is a two-stage process. The first stage is non-invasive and includes a thorough review of the clinical history and examination with particular focus on the organ systems and the most likely disease processes (see Box 26.1). Disease risk factors and symptom patterns may suggest a particular diagnosis or disease process and may help focus the diagnostic plan. A thorough physical examination, including a careful and complete examination outside the system involved looking for signs of primary or secondary involvement elsewhere, may similarly shorten the time to diagnosis.

Box 26.1 Investigation of an incidental, scan-detected abdominal mass. Stage 1: non-invasive investigations

It will not always be necessary to proceed to the second stage, that of invasive investigations (Box 26.2). The indications for this and the pattern of investigations chosen in stage 2 will depend on the findings from the non-invasive investigations of stage 1. Invasive or physiologically disruptive diagnostic procedures may include imaging guided biopsies, arteriography, barium enema, endoscopic procedures and associated biopsies or, less frequently, diagnostic laparoscopic or open surgery. All invasive investigations incur some risk, discomfort and expense. The patient must be fully informed about this and must be able to comply with the requirements of the investigation. Hence, a patient who cannot remain still may not be suitable for a percutaneous biopsy. A patient who suffers from claustrophobia may not be suitable for an MRI scan.

Biliary Incidentalomas

Asymptomatic gallstones

Prophylactic cholecystectomy may be justifiable for gallstones larger than 2.5 cm; the risk of acute cholecystitis may be higher due to a higher risk of gallstone impaction in Hartmann’s pouch causing gallbladder outflow obstruction and acute cholecystitis. Prophylactic cholecystectomy may also be justified for diabetic patients with asymptomatic gallstones as acute cholecystitis may be more dangerous in these patients. Other situations where prophylactic cholecystectomy may be justified for asymptomatic gallstones include the very young, haemolytic disease, non-hepatic transplantation and porcelain gallbladder, where chronic infection associated with gallstones has resulted in calcification of the gallbladder wall (Figs 26.1 and 26.2). In all such cases, the clinical decision making should include appropriate specialist advice.

Incidentally detected gallbladder polyps

Polyps in the gallbladder are usually asymptomatic and are frequently detected by upper abdominal ultrasound carried out for other reasons. On ultrasound scanning, gallbladder polyps are differentiated from gallstones by their lack of mobility within the gallbladder (as they are attached to the gallbladder wall), and by the lack of acoustic shadowing that is a usual ultrasound scan feature of gallstones. Gallbladder polyps may be non-neoplastic or neoplastic. Non-neoplastic gallbladder polyps are made up of cholesterol and attached to the gallbladder epithelium so they do not move. Neoplastic (or adenomatous) gallbladder polyps arise from the gallbladder epithelium. Most gallbladder polyps are small (less than 1 cm) and most small gallbladder polyps are non-neoplastic. The risk that a polyp is an unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma is very low but increases with increasing polyp size. For this reason, polyps greater than 1 cm are generally removed by cholecystectomy. For polyps less than 1 cm the possibility of a small carcinoma is addressed by repeating the ultrasound in 3–6 months. If the lesion is stable the ultrasound is repeated at 12 months. A carcinoma would be expected to increase in size whereas small adenomatous polyps and cholesterol polyps are unlikely to change. Polyps larger than 1 cm or that enlarge should be regarded as suspicious, removed by cholecystectomy and submitted for histopathology.

Asymptomatic common bile duct dilatation

In normal patients younger than 60 years of age the upper limit of common bile duct size on ultrasound is 6 mm. This limit increases by 1 mm per decade after 60 years of age. The bile duct tends to be a little wider in women and also after cholecystectomy. Other causes of bile duct dilatation are listed in Box 26.3. The likelihood that incidentally detected common bile duct dilation is due to significant pathology and is revealing extrahepatic cholestasis is increased if the liver function tests, especially the serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels, are abnormal, so these are usually performed first. The likelihood of a malignant cause such as pancreatic head carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma is increased if the tumour marker CA-19-9 is elevated, so this too should be checked in the phase of non-invasive investigations, especially if the serum bilirubin and serum alkaline phosphatase level are raised.

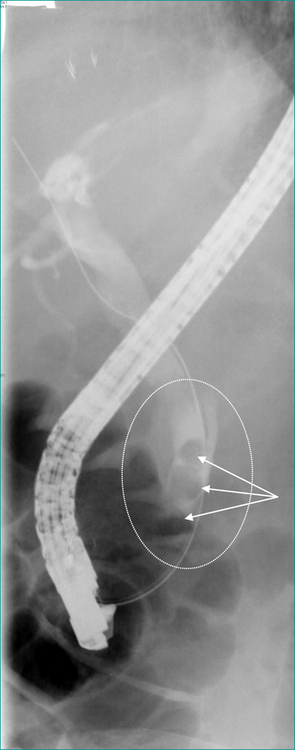

Asymptomatic choledocholithiasis

Where it is available, ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic stone extraction is the most common treatment for common bile duct stones that do not pass spontaneously (Fig 26.3). If ERCP is not available the duct is usually cleared by laparoscopic or open surgery. If the gallbladder is still present it is usually removed at the same operation. Thus, if ERCP is not readily available or, in patients not needing urgent clearance of the bile duct, a two-stage treatment (ERCP and subsequent surgical removal of the gallbladder) can on occasion be condensed into a single phase treatment by omitting the ERCP and utilising a single surgical procedure to remove the gallbladder and clear the bile duct, usually laparoscopically.

Choledochal cysts

Choledochal cysts may occur anywhere in the biliary tree. They may be focal or diffuse, single or multiple. They are classified on the number of cysts present and on their position in the intra- or extrahepatic biliary tree (Table 26.1). Though not primarily caused by bile duct obstruction or by strictures, tumours or stones, all these problems may develop in association with them and may in turn lead to complications such as cholestasis (obstructive jaundice), infection in the biliary tree (cholangitis), impaired hepatic function (liver failure), hepatocellular loss and hepatic fibrosis (cirrhosis) and bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma).

| Site of cyst | Classification | ERCP findings |

|---|---|---|

| Extrahepatic | I | Solitary fusiform cyst |

| II | Supraduodenal diverticulum | |

| III | Intraduodenal diverticulum (choledochocoele) | |

| IVB | Multiple extrahepatic cysts | |

| Extrahepatic and intrahepatic | IVA | Extra and intrahepatic cysts |

| Intrahepatic | V | Multiple intrahepatic cysts (Caroli’s disease) |

ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

The discovery of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct dilation consistent with choledochal cysts necessitates further investigation, initially by assessment of liver function and by MRCP or CT cholangiography. Masses associated with choledochal cysts anywhere in the biliary tree may be due to cholangiocarcinoma and should be assumed to be so until proven otherwise.

Pancreatic Incidentalomas

Unexpected imaging detected masses in the pancreas may be cystic or solid and may be derived from stromal, exocrine or endocrine elements of the pancreas. Lymph glands lying in or adjacent to the pancreas may also be responsible for incidentally detected asymptomatic pancreatic masses. As with incidentalomas elsewhere, the first step in non-invasive investigation of pancreatic incidentalomas is always to revisit the clinical history and examination. A past history of epigastric pain may correspond to a previous episode of pancreatitis. Epigastric pain associated with back pain may be consistent with pancreatic cancer, as would a history of nausea or weight loss. A palpable epigastric mass is possible and should be looked for but is unlikely unless a pancreatic lesion is very large. An enlarged supraclavicular lymph node, an umbilical nodule or a hepatic mass may betray previously unsuspected metastatic disease.

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas

These are usually multilocular and commonly have solid elements or irregular thickening of their walls. They are often asymptomatic and so are liable to present as incidental imaging findings. The most common pancreatic cystic neoplasms are serous cystadenoma and mucinous cystadenoma. Less common mixed solid and cystic pancreatic neoplasms include microcystic adenomas and papillary and cystic tumours (Ch 17). Though it may be difficult, distinguishing between these neoplastic lesions is important as they have quite different malignancy risks. If a lesion can be demonstrated to be a serous cystadenoma by detection of tiny flecks of calcium in the cysts wall on CT or MRI scanning and on endoscopic ultrasound suggestive cytology features and elevated cyst fluid tumour marker levels, then no treatment is required as pancreatic serous cystadenomas are benign with no malignant potential. Conversely, if the lesion is a mucinous cystadenoma and the patient is fit, resection should be considered as some of these are malignant (cystadenocarcinoma) even though they may look histologically benign on biopsy. Pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma carries a much higher chance of cure than does the more common pancreatic adenocarcinoma, especially if detected early and resected completely (see Ch 17).

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Cure rates for pancreatic adenocarcinoma are dismal, but perhaps the best chance of cure will be for the occasional small, asymptomatic, incidentally detected case. All such cases should be referred promptly for specialist evaluation. Most will require some form of invasive investigation to secure the diagnosis, most commonly endoscopic ultrasound scanning and ERCP. Those that are malignant will also require staging investigations before pancreatic resection is considered (see Ch 17).

Endocrine pancreatic neoplasms

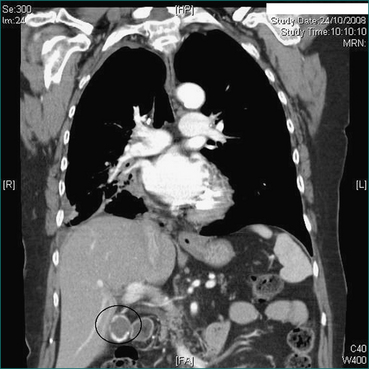

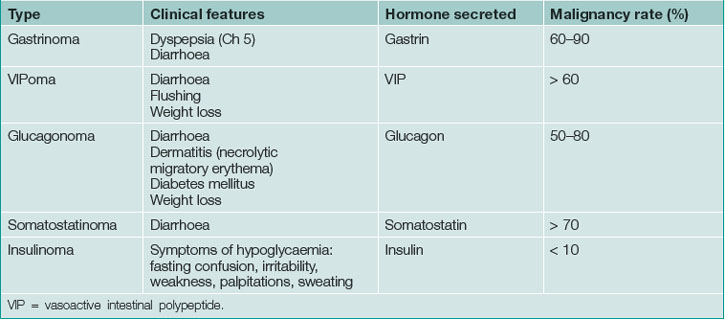

Endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas may be functional (secretory) or non-functional (non-secretory). Functional endocrine tumours of the pancreas usually present with symptoms caused by an excess of the secreted hormone and are rarely incidental. Non-functional endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas are more prone to be detected as incidental findings (incidentalomas) on intravenous contrast CT scans (Table 26.2) where they appear as small, well-vascularised, mass lesions (Fig 26.4). In general, endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas grow very slowly or not at all and, as with lymph nodes, investigation and management can be problematic as their true nature can be very difficult to determine with certainty. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasound scanning may help clarify the diagnosis, especially if endoscopic ultrasound scanning guided fine needle aspiration biopsy and cytology can be carried out (see Ch 17).

Hepatic Incidentalomas

Simple hepatic cysts

Simple hepatic cysts are more common in women than men, are lined by thin, smooth, epithelium and contain serous fluid. They do not connect with the biliary tree and they vary in size, ranging from only just detectable on scan (5 mm) to greater than 20 cm and palpable. These rarely require treatment although very large cysts may be symptomatic (abdominal discomfort or pain) and very occasionally they may cause abnormal liver function tests or even obstructive jaundice by compression of the bile duct. Simple cysts may be multiple, but this finding should raise the possibility of polycystic liver disease (Fig 25.5).

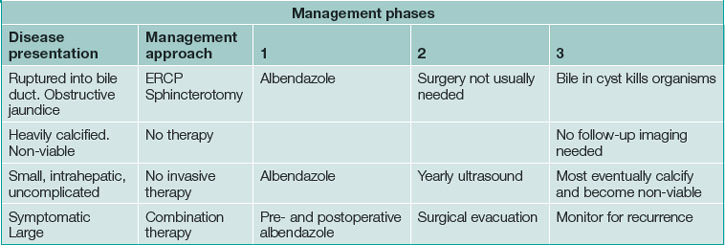

Hepatic hydatid cysts

Dead hydatid cysts tend to calcify and to collapse and may then show up on scans or on plain x-rays as amorphous, coarse, heavily calcified lesions with little or no residual cystic component. Provided other potentially viable hydatid cysts are excluded on the abdominal scan and chest x-ray examination, further diagnostic investigations are not usually required and calcified, non-viable hydatid cysts rarely require treatment.

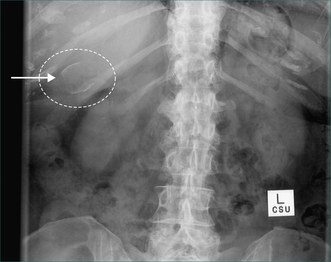

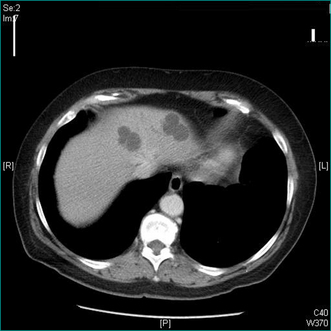

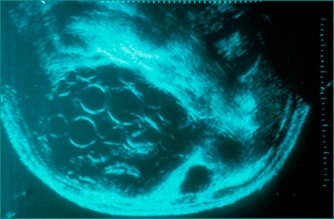

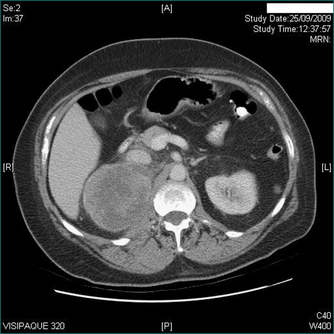

Viable hydatid cysts show no calcification or incomplete calcification and non-uniform internal density due to daughter cysts or hydatid debris within the main cyst (Figs 26.6 and 26.7). Potentially viable hydatid cysts require careful investigation, even if they are truly asymptomatic, because of the risk of rupture into the peritoneal cavity. Hepatic hydatid disease must always be excluded before needling of hepatic cysts is considered as this procedure may result in leakage of hydatid cyst fluid containing viable hydatid protoscolices and cause intraperitoneal dissemination of the disease. Leakage of hydatid fluid into the peritoneal cavity may also cause acute hypersensitivity reactions. Hydatid serology may be positive in the presence of a non-viable cyst and is occasionally negative in the presence of a viable cyst. However, a positive test is a useful way of confirming that a patient has had hydatid disease at some time, but is not diagnostic of active hydatidosis.

Figure 26.6 Photograph taken during an operation on an hepatic hydatid cyst. Large liver hydatid cyst open to show daughter cysts within it. Hydatid daughter cysts cause the circular shadows seen within larger hydatid cysts on US and CT scans (see Fig 26.7).

Potentially viable hydatid cysts that are completely intrahepatic may safely be kept under observation after treatment with an antihelminthic agent such as albendazole. Cysts that discharge into the biliary tree may present with jaundice and are usually treated by endoscopic drainage to clear the bile duct. Further invasive treatment is not usually needed in these cases as bile contamination of the cysts kills the organisms, rendering the residual hepatic hydatid cyst non-viable. Cysts that are large involve the surface of the liver, become infected, are associated with compromise of liver function or are symptomatic usually do need treatment. This is usually surgical evacuation of the cyst plus an antihelminthic agent given before and after surgery to reduce the risk of postsurgical recurrence. See Table 26.3 for treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts.

Solid hepatic incidentalomas

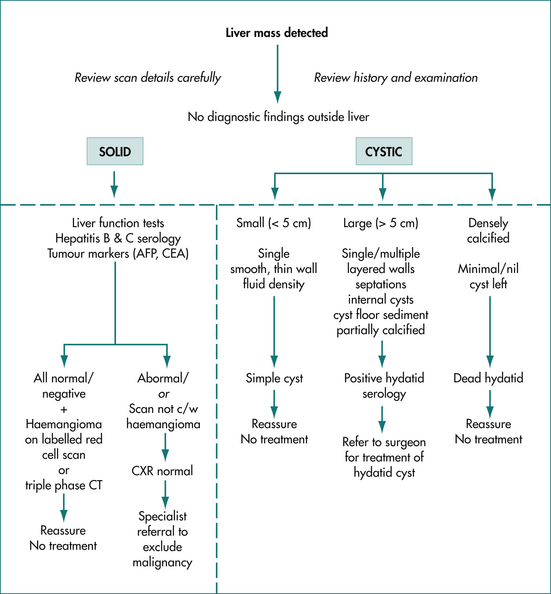

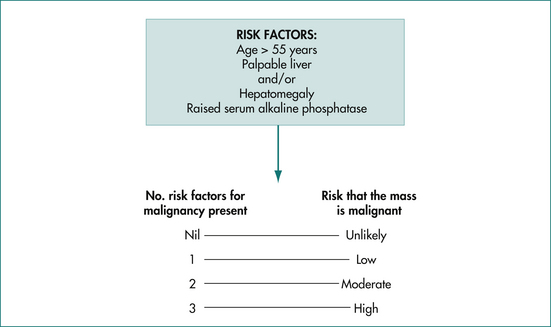

Solid hepatic lesions are more likely to be malignant than are cystic hepatic lesions. However, approximately 75% of solid liver lesions presenting as incidentalomas will be benign and the majority will also be non-neoplastic. The chance of a solid hepatic lesion being malignant does increase with age (especially over 55 years), if the lesion is palpable, if the liver function tests are abnormal and if known risk factors for primary or metastatic liver disease are present (Fig 26.8). These factors should be taken into consideration in assessing the risks associated with any particular solid hepatic incidentaloma.

Hepatic metastases

Solid hepatic incidentalomas identified on scanning may not be primary liver lesions at all. They may be metastases acting as the diagnostic clue for a primary malignancy elsewhere. This should be suspected in all cases of solid hepatic incidentaloma and the finding of one or more solid hepatic incidentalomas mandates exclusion of this possibility. Multiple solid lesions are more likely to be malignant than benign and are more likely to be metastases than primary liver tumours.

A careful history and physical examination are required. Physical examination should include the skin (for melanoma), breasts, lungs, lymph nodes (especially supraclavicular nodes), genitals, anus and rectum as well as the abdomen for other abdominal masses. A chest x-ray examination should be carried out looking for a lung primary or pulmonary metastases. Upper and lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy should be considered, particularly if the serum carcinoembryonic antigen level is elevated, looking for stomach or colon cancer (Fig 26.9). If a lesion can be found outside the liver, the diagnostic problem may be more simply and safely solved by biopsy of that lesion than of the liver lesion.

Summary of solid hepatic incidentalomas

Hepatic haemangiomas are common, generally harmless and asymptomatic, rarely require treatment and should not be biopsied. The majority of solid lesions remaining after hepatic haemangioma has been excluded are also benign. However, all must be regarded as possibly malignant, particularly in older people, when the liver or a liver mass is palpable, when liver function is disturbed, when there is a history of hepatitis B or C or when metastatic disease is possible. The index of suspicion of a malignant mass rises according to the number of risk factors present (Fig 26.10). Clinical, biochemical and imaging characteristics are useful in assessing the risk of malignancy, but none of these can reliably distinguish benign from malignant neoplasms in the liver. The final diagnosis is usually made on a combination of findings, but may depend on histopathology, either from a biopsy or on excision of the whole lesion. Biopsy should not be undertaken without prior surgical consultation.

Radioactive pharmaceutical imaging in the investigation of hepatic masses

Biliary scan

Biliary scanning can also be useful in characterising liver masses when the diagnosis remains unclear after cross-sectional imaging, liver-spleen scanning and labelled red cell scanning. Masses caused by fibronodular hyperplasia contain functioning hepatocytes, but have few biliary drainage radicals. Fibronodular hyperplasia will therefore tend to take up and hold a radiolabelled tracer excreted into the bile. Therefore, fibronodular hyperplasia will initially appear isodense with the rest of the liver. But, due to its deficiency of biliary drainage radicals, fibronodular hyperplasia will hold the tracer and therefore appear as a delayed hot spot on the biliary scan after the normal liver has cleared the radiolabelled tracer into the biliary tree.

Invasive diagnostic procedures in the diagnosis of hepatic masses

Retroperitoneal Masses

Lymph node masses

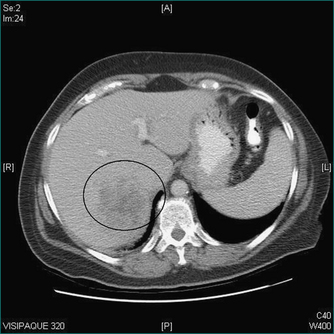

Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy may be reactive (inflammatory) or neoplastic (malignant). Reactive lymphadenopathy is usually a response to inflammation somewhere in the draining field of that lymph node but can also be part of a diffuse inflammatory response. Reactive nodal enlargement is usually modest, non-progressive and temporary. Malignant retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy tends to be progressive and may be quite bulky, particularly when due to malignant lymphoma (Fig 26.11). Lymphadenopathy due to metastatic carcinoma is usually slowly but inexorably progressive whereas that due to lymphoma may fluctuate, particularly early in the course of the disease. Close questioning of lymphoma patients may uncover systemic symptoms (e.g. fever, rash, pruritus) and careful examination may detect enlarged lymph nodes in the groin, axilla or neck. In patients with metastatic skin cancer (squamous cell carcinoma or melanoma), there may be a history of a mole or lump, which may have been ignored, may have regressed or may have been previously removed. Some of the more common visceral primary sites leading to unexpected retroperitoneal masses (usually nodal) include the colon, stomach, pancreas and testis. There may be previously unrecognised or undetected symptoms arising from the nodal mass or from the primary lesion, or there may be signs in the organ draining to the site. There may also be non-specific symptoms consistent with malignancy, such as lethargy or weight loss.

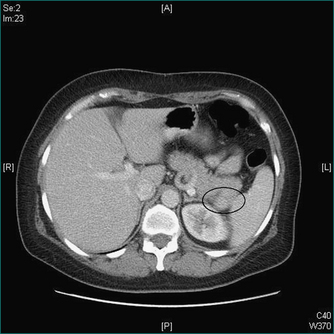

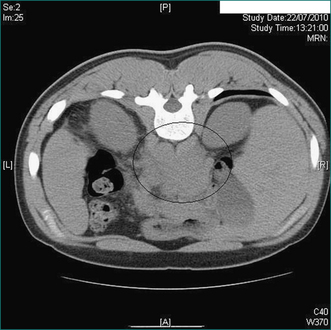

Figure 26.11 Retroperitoneal mass (circle). CT taken at time of needle biopsy. Histopathology diagnosis lymphoma.

Metastatic carcinoma in retroperitoneal nodes denotes disseminated disease that usually cannot be cured by surgery. The aim here should be to carry out and to take into consideration the findings from all investigations that may advance the diagnosis and development of the treatment plan, but to avoid unhelpful investigations and inappropriate or misguided treatments that could be instituted on the basis of inadequate or inappropriate investigations. Other simple investigations such as a tumour marker screen and a chest x-ray may help characterise and stage the disease, but will not be specifically diagnostic (see Ch 15). Definitive diagnosis is generally based on histopathology, established by biopsy of a metastasis or of the primary tumour and treatment is generally non-surgical.

Extraadrenal endocrine tumours

These can be functional or non-functional and should be particularly thought of for those retroperitoneal incidentalomas that are close to the kidney. A family history of an endocrine neoplasm, a past history of hypertension and symptoms such as episodic palpitations (e.g. phaeochromocytoma) or flushing and diarrhoea (e.g. carcinoid) should also arouse suspicion of an endocrine neoplasm. If an endocrine tumour is a possibility (Fig 26.12), a search for other endocrine tumours (multiple endocrine neoplasia; Box 26.4) should also be undertaken, particularly in the thyroid, parathyroid and adrenal glands (see Table 25.4). Invasive investigations must be avoided until the secretory status of the tumour has been ascertained.

Table 26.4 Unexpected retroperitoneal mass: basic diagnostic possibilities

| Tissue of origin | Benign neoplasm or process | Malignant neoplasm |

|---|---|---|

| Retroperitoneal tissue | Benign | Malignant |

| Lymph nodes | Reactive lymphadenopathy |

Biopsy of retroperitoneal incidentalomas

Other manoeuvres such as bone marrow biopsy or lymph node biopsy in the neck, axilla or groin may remove the need for an abdominal operation to make the diagnosis of lymphoma after the discovery of a retroperitoneal mass. However, if the lesion is a lymphoma or a mesenchymal tumour, needle biopsy may well be non-diagnostic. The pathologist may still not be able to differentiate benign reactive changes from a lymphoma unless an incisional or excisional node biopsy is done. If the lesion is a sarcoma, needle aspiration cytology may be non-diagnostic in very well differentiated sarcoma as the cells may not look particularly abnormal, particularly on cytology. Core biopsy will be more accurate, but care in selecting the appropriate case and biopsy site is essential as a needle biopsy of a sarcoma may compromise subsequent treatment by seeding along the needle track. Detailed staging scanning should be undertaken for all suspected mesenchymal tumours, but biopsy of potentially sarcomatous lesions is best deferred until the advice of a surgical oncologist has been sought.

Mesenteric Masses

Mesenteric lymph node masses and neoplasms

The investigation of these may be approached in the same way as for retroperitoneal masses. Like the retroperitoneum, the mesentery contains many lymph nodes and unexpected masses in the mesentery most commonly arise in these lymph nodes. Non-lymphatic mesenchymal neoplasms are less common. A rare form of fibrotic mass known as a desmoid tumour (also known as ‘aggressive fibromatosis’) can also present as an unexpected mass in the small bowel mesentery or occasionally, in the pelvis, on CT or ultrasound scanning (Fig 26.13).

Diagnosis of mesenteric masses, especially desmoid tumour, can be difficult to secure as small biopsies are often inconclusive. Final diagnosis may rest on tissue obtained by surgical excision. Metastatic carcinoma in a mesenteric mass should trigger a search for a primary site as outlined for metastatic disease found in the liver or in retroperitoneal nodes. Mesenteric desmoid tumour may be associated with Gardner’s syndrome (Ch 22) in which case there should be other features of that syndrome identifiable and a relevant family history should be sought. Desmoid tumours that arise in the pelvis are often asymptomatic until they become very large.

Peritoneal masses

The majority of these are metastases due to transcoelomic spread of pelvic (especially ovarian) or abdominal (especially gastric) adenocarcinomas but any intraabdominal cancer can be the primary site. Primary malignancies of the peritoneum are uncommon conditions that occur in two forms: mesothelioma and primary peritoneal carcinoma. A background history of asbestos exposure should be sought if mesothelioma is suspected. Primary peritoneal carcinoma is very similar to ovarian carcinoma. These two malignancies usually present with abdominal or pelvic symptoms and signs, particularly palpable masses and ascites. A careful history may also reveal non-specific symptoms such as mild abdominal discomfort, weight loss, malaise and lethargy. They are rarely incidental scan findings. A definitive diagnosis may be made on cytology from samples of peritoneal fluid or needle biopsy, but open biopsy is still occasionally required.

Key Points

Carling T. Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome: genetic basis for clinical management. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:7-12.

Friedel D.M., Abraham B., Georgiou N., et al. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms. South Med J. 2010;103(1):51-57.

Garcea G., Ong S.L., Rajesh A., et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. A diagnostic and management dilemma. Pancreatology. 2008;8(3):236-251.

Levy M.J., Clain J.E. Evaluation and management of cystic pancreatic tumors: emphasis on the role of EUS FNA. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:639-653.

Metcalfe M.S., Wemyss-Holden S.A., Maddern G.J. Management dilemmas with choledochal cysts. Arch Surg. 2003;138:333-339.

Petrov M.S., Savides T.J. Systematic review of endoscopic ultrasonography versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for suspected choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg. 2009;96(9):967-974.

Rubens D.J. Hepatobiliary imaging and its pitfalls. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:257-278.

Schipper H.G., Kager P.A. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic echinococcosis: an overview. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2004;241:50-55.

Strasberg S.M. Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(26):2804-2811.

Stratakis C.A., Carney J.A. The triad of paragangliomas, gastric stromal tumours and pulmonary chondromas (Carney triad), and the dyad of paragangliomas and gastric stromal sarcomas (Carney-Stratakis syndrome): molecular genetics and clinical implications. J Intern Med. 2009;266(1):43-52.