20 Abdominal distension

Case

A 32-year-old woman presents with a 6-day history of progressive abdominal distension and nausea. She had recently been an inpatient with an episode of acute pancreatitis. The aetiology of the pancreatitis was familial pancreatitis, with her grandmother, father and one brother having episodes of recurrent pancreatitis. She looked well, was afebrile and was not jaundiced or pale. Abdominal examination revealed a moderately distended abdomen that was tense but not tender. The bowel sounds were normal. There was evidence of shifting dullness and a fluid thrill. A provisional diagnosis of ascites was made.

Preliminary Examination of the Abdomen

2. Fluid or ascites

Intraperitoneal fluid collection is associated with dullness to percussion in the flanks with the patient lying supine. The dullness is described as shifting dullness because the upper limit of the dullness moves in relation to the abdominal wall as the patient is rolled onto the side. Massive ascites is also associated with a fluid thrill felt in one flank after tapping in the other. The distension is less globally distributed with ascites than with gaseous distension of the abdomen, with the effect that the flanks tend to sag.

3. Faeces

Stool can accumulate in the colon to produce abdominal distension. This can cause gaseous distension of more proximal bowel. The degree of distension tends to be less than can occur with ascites or bowel obstruction. The faeces can be recognised as firm to hard lumps that are indentable when prodded with the tip of the examining finger (Ch 11). The segments of colon overlying the brim of the pelvis on the left and right sides may be more prominent to the examining hand.

History and Further Examination

A classification of the causes of abdominal distension is presented in Table 20.1 and relevant symptoms are listed in Table 20.2. The duration of abdominal distension and its association with abdominal pain are key questions. Thus, abdominal pain should not usually be expected to be a feature, except with abdominal distension due to gas in bowel obstruction; with the other causes, there may be milder discomfort due to stretching of the parietal peritoneum or the capsule of an organ. Localised pain can occur with organ swelling. Similarly, the speed of development for most causes is slow, except with abdominal distension from gas, in which case it can be fast. Tense swelling of the abdomen due to fluid or a large tumour can cause increased intraabdominal pressure leading to heartburn, nausea, vomiting or dyspnoea (from elevation of the diaphragm). The specific clinical features for each cause are described below.

Table 20.1 Classification of causes of abdominal distension: the ‘six Fs’

| Cause | Example | Distension |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Flatus (gaseous distension) | ||

| Bowel obstructed | ||

| Open | Generalised | |

| Closed | Sigmoid volvulus | Localised |

| Caecal volvulus | Localised | |

| Bowel not obstructed | ||

| Paralytic ileus | Generalised | |

| Pseudo-obstruction | Generalised | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Generalised | |

| Acute gastric dilatation | Localised | |

| Gas bloat | Generalised | |

| 2. Fluid (ascites) | See Table 20.3 for detail | Generalised |

| 3. Faeces | Localised | |

| 4. Fat | Generalised | |

| 5. Fetus | Localised | |

| 6. Filthy big tumour (organomegaly) | ||

| Liver | See Chapter 19 | Localised |

| Spleen | See Chapter 19 | Localised |

| Ovary | Ovarian cyst | Localised |

| Uterus | Fibroids | Localised |

| Kidney | Polycystic kidney | Localised |

| Hydronephrosis | – | Localised |

| Bladder | Obstructed bladder | Localised |

| Mesentery | Tumour | Localised |

| Retroperitoneum | Tumour | Localised or generalised |

Table 20.2 Possible symptoms with abdominal distension

| Symptom | Relevance/significance |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain: |

Clinical Features

Gaseous distension of the bowel (flatus)

Mechanical obstruction of the bowel (small or large)

The distension is associated with other features of bowel obstruction, namely colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and constipation. The diagnosis and management of bowel obstruction is discussed in Chapter 4.

Paralytic ileus

This is often preceded by an abdominal operation. Operations involving retroperitoneal structures (e.g. repair of an aortic aneurysm), operations during which there is considerable handling of the bowel and prolonged operations are more prone to paralytic ileus. Irritation of the retroperitoneum as occurs with severe pancreatitis or a spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage can precipitate an ileus. An intraabdominal inflammatory process such as acute diverticulitis and biochemical disturbances such as hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and chronic kidney disease can also precipitate an ileus. In contradistinction to a mechanical bowel obstruction, there is no colicky pain with paralytic ileus, just the discomfort associated with distending the parietal peritoneum. The condition settles spontaneously with correction or resolution of precipitating factors. Gastric decompression and fluid replacement (and sometimes intravenous hyperalimentation) are required while resolution occurs.

Pseudo-obstruction

The time course of pseudo-obstruction is more protracted than with mechanical obstruction; the degree of distension may fluctuate considerably. Pseudo-obstruction is discussed in Chapter 7.

Irritable bowel syndrome

This may be associated with chronic fluctuating abdominal distension of moderate degree. This condition is considered in detail in Chapter 7.

Gas bloat

This particular chronic problem can occur as a complication of antireflux surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux (Ch 1). It results from air swallowing in a patient who has a diminished ability to belch because of their surgery. The degree of distension of stomach and bowel can vary considerably. It is generally worse postprandially. There is usually some degree of discomfort. This may vary from a vague feeling of fullness to a more localised epigastric discomfort to central abdominal colicky pain. It may be relieved to a degree by passage of flatus.

Ascites (fluid)

The main causes of ascites and their prevalence are listed in Table 20.3. These are:

| Cause | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 80 |

| Malignancy | 10 |

| Heart failure | 5 |

| Tuberculosis | 1 |

| Other: hypoproteinaemia caused by starvation (kwashiorkor and malignancy) or excessive loss (protein-losing enteropathy, nephrotic syndrome); pancreatic ascites; chylous ascites | 4 |

Faecal impaction of the colon (faeces)

This is a chronic problem caused by chronic constipation, and is most commonly seen in elderly people. The various causes of constipation are considered in detail in Chapter 11. Abdominal distension is an uncommon feature of the most severe end of the spectrum. A history of infrequent, usually hard bowel actions is expected. A history of laxative abuse is also very common. Lower abdominal colicky pain may be associated. When such pain occurs it should be relieved by the passage of flatus or a large evacuation of the bowel.

Investigations

The appropriate investigations to evaluate abdominal distension are detailed below.

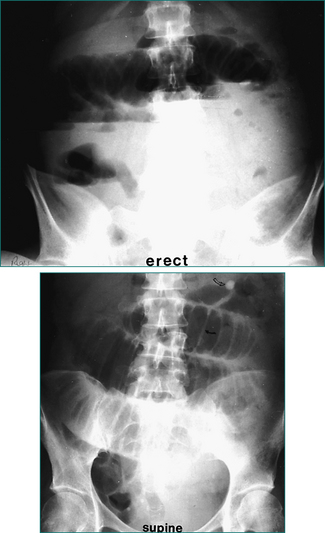

Plain radiology of the abdomen

This may demonstrate a small or large bowel obstruction and paralytic ileus (Figs 20.1 and 20.2) as well as faecal loading. The fluid of ascites may give a ‘ground glass’ appearance, a non-specific vague increased whiteness to the abdominal cavity.

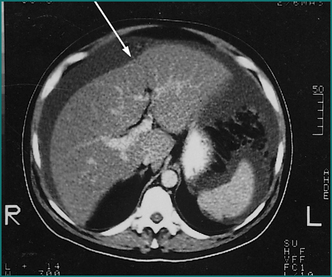

Ultrasound or CT of the abdomen

This will confirm the presence of ascites (Fig 20.3) and define organomegaly.

Blood tests

Liver function tests may indicate underlying chronic liver disease (Ch 24). A pregnancy test will confirm the presence of pregnancy.

There is no specific relevant test for obesity. Measure the weight and height to calculate the body mass index (BMI = weight [kg] divided by height squared [m2]). A BMI of 30 or over indicates frank obesity; a BMI of 40 or over indicates severe obesity (Ch 26). The diagnosis can usually be made on clinical grounds.

Of the various causes of abdominal distension, only ascites will be discussed in further detail in this chapter. Bowel obstruction is discussed in Chapter 4. Constipation is discussed in Chapter 11. Pregnancy is beyond the scope of this text.

Diagnosis of Ascites

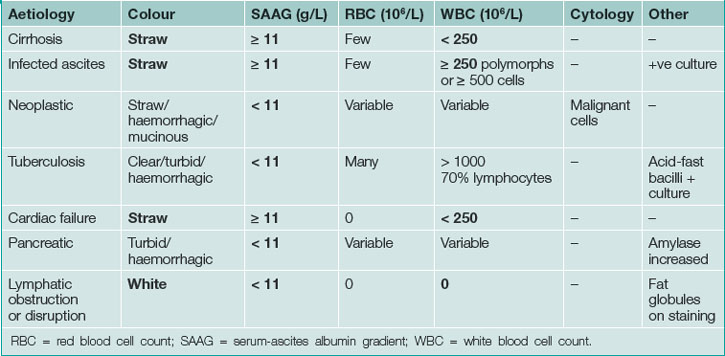

The features of ascitic fluid are summarised in Table 20.4.

Serum-ascites albumin gradient

Calculate this by subtracting the ascitic fluid albumin from the serum albumin value; the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) correlates with portal pressure. If the SAAG is 11 g/L or more, then portal hypertension is the likely diagnosis (97% accurate). Peritoneal carcinomatosis, tuberculosis and pancreatic ascites have a gradient under 11 g/L (Table 20.5).

Table 20.5 Classification of ascites by serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG)

| SAAG: high (≥ 11 g/L) | SAAG: low (< 11 g/L) |

|---|---|

Cells

Examination of the ascites for polymorphonuclear cells is important to diagnose spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A cell count of 250 × 106 polymorphs/L (250 polymorphs/mm3) or more, or 500 × 106 white cells/L (500 cells/mm3) or more, is strongly suggestive of the diagnosis. The cause is usually a gram-negative organism sensitive to treatment with a third-generation cephalosporin (e.g. cefotaxime).

Management of Ascites

This depends on the underlying diagnosis, as follows.

Malignant ascites

It is important to try to establish the site of the primary tumour because systemic hormonal or chemotherapy can result in regression of the intraperitoneal tumour and the ascites, especially if the primary site is colonic, gastric, breast or ovary. Clinical re-examination of breasts and abdomen may be helpful. The investigations used to establish the common sites of the primary tumour, namely colon, stomach, pancreas, ovary and breast, are shown in Table 20.6.

Table 20.6 Investigations for primary tumour in patients with malignant ascites

| Site of primary | Relevant investigations |

|---|---|

| Colon | Colonoscopy and biopsy |

| Stomach | Gastroscopy and biopsy |

| Pancreas |

CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; CT = computerised tomography; EUS = endoscopic ultrasound.

In the event that the primary site is colon, stomach or pancreas, local therapy may be required to palliate the discomfort of distension. The therapeutic options are limited and none is really satisfactory. They include (1) repeated major paracentesis, which is time-consuming and results in the development of hypoalbuminaemia and malnutrition; and (2) peritoneovenous shunting, which can block and can be complicated by coagulopathy. Frequently, the best option is analgesia and general support.

Key Points

Runyon B.A., Montano A.A., Akriviadis E.A., et al. The serum-ascites albumin gradient is superior to the exudate/transudate concept in the differential diagnosis of ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:215-220.

Saadeh S., Davis G.L. Management of ascites in patients with end-stage liver disease. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4:175-185.

Smith E.M., Jayson G.C. The current and future management of malignant ascites. Clin Oncol. 2003;15:59-72.

Williams J.W.Jr., Simel D.L. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have ascites? How to divine fluid in the abdomen. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267:2645-2648.