Abdominal Cerclage of the Cervix Uteri

Typically, cervical cerclage is performed via the vaginal route. The simple purse-string McDonald closure and the submucosal Shirodkar closure are accomplished with a low level of bleeding and relatively little pain, and within a short time.

When the cervix is extremely short as a result of obstetric injury, deep conization, multiple excisional/ablative procedures, or virtual amputation, vaginal placement of a constricting suture or band may be difficult or impossible to perform. In fact, anecdotal accounts about ureteral ligation have been reported in conjunction with McDonald suture placement.

Clearly, the observed lengthening of the cervix following cerclage cannot be accounted for by narrowing the cervical canal. It is obvious that the increased cervical length is attributable to inclusion of the uterine isthmus within the suture.

A laparotomy is required for this technique. Five steps are critical for the successful and safe performance of abdominal cerclage: (1) elevation of the uterus to expose the isthmus and cervix, (2) identification of the uterine vessels, (3) precise identification of the position of the ureters, and (4) placement of the cerclage band above the uterosacral ligaments by (5) location of an avascular plane between the uterine vessels and the isthmus.

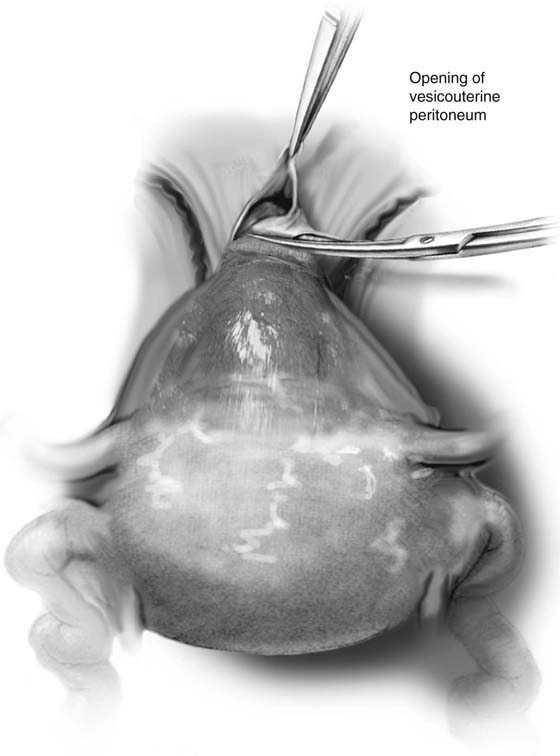

This operation is performed during the second trimester at approximately 14 to 16 weeks’ gestation. The fundus is grasped between the operator’s thumb and forefinger over a lap pad. A space is opened in the vesicouterine and rectouterine peritoneum (Fig. 17–1). The bladder is gently pushed inferiorly. The peritoneum will be advanced at the end of the operation to cover the strap. The job of holding the uterus is transferred to an assistant once proper traction and positioning have been achieved.

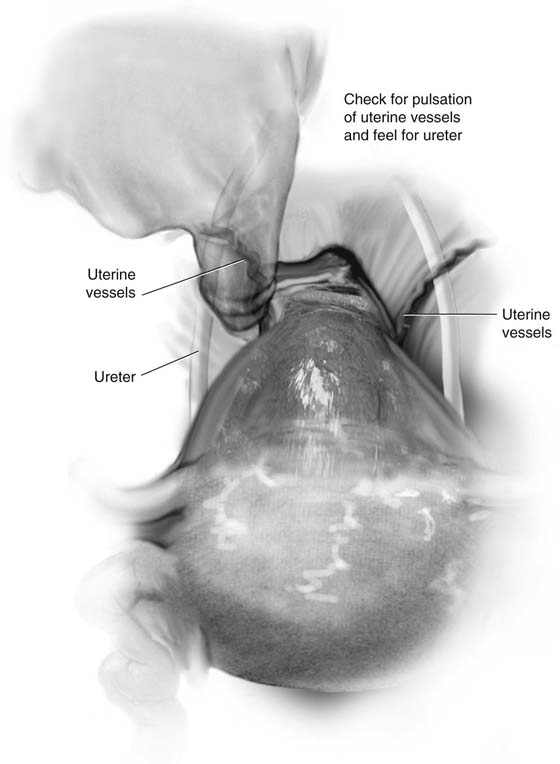

The uterosacral ligaments are identified. The uterine vessels are felt pulsating as they ascend the side of the uterus (Fig. 17–2). The pelvic ureter is identified relative to the uterine vessels and the uterosacral ligament. An avascular space is identified between the uterine vessels and isthmus. If this cannot be seen, then the peritoneum should be opened over the uterine artery similar to skeletonization so that a space can be seen.

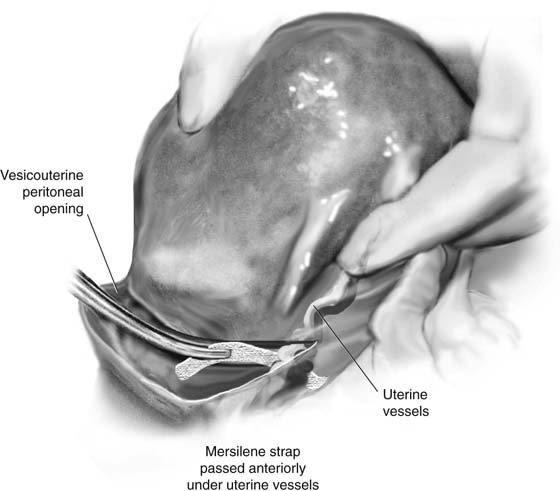

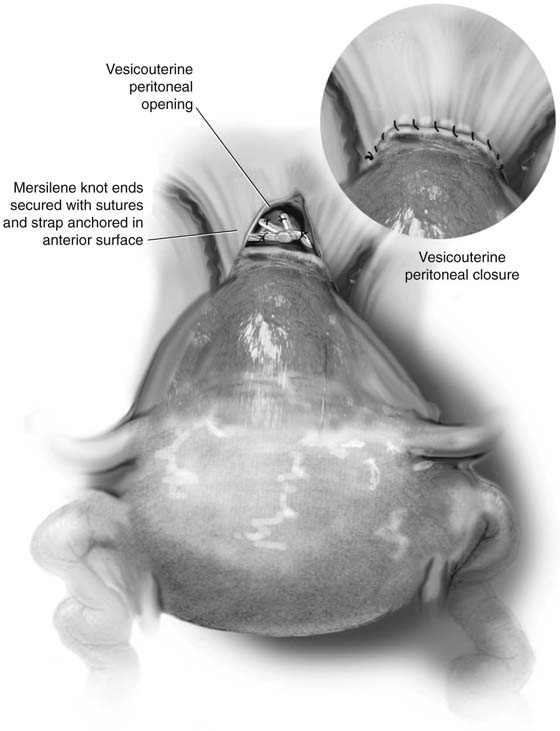

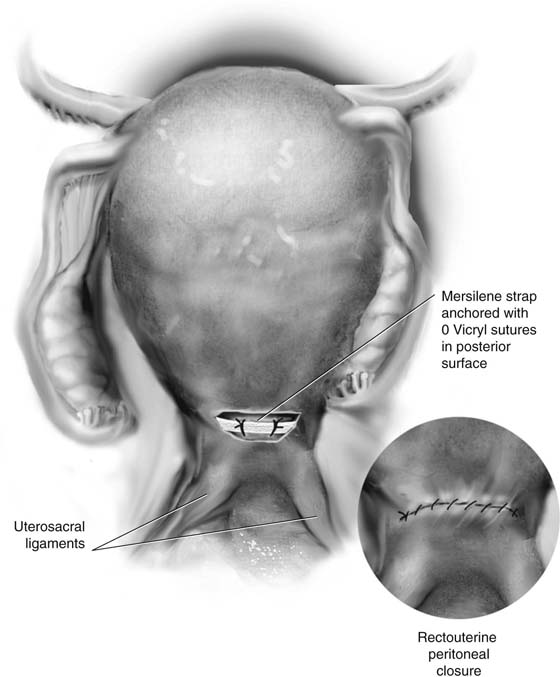

The needle or carrier is passed anteroposteriorly above the uterosacral ligament and posteroanteriorly again above the uterosacral ligament on the opposite side (Fig. 17–3). The strap of Mersilene mesh is gently tightened and tied into place (Fig. 17–4). The anterior and posterior surfaces are anchored to prevent migration up or down with 0 Vicryl sutures (Fig. 17–5). The vesicouterine and rectouterine peritoneum is folded over the strap and sutured closed with 3-0 Vicryl.

FIGURE 17–1 The vesicouterine and rectouterine folds are incised. The bladder is pushed down with a sponge stick to expose the cervicocorporal junction of the uterus.

FIGURE 17–2 The uterine vessels are palpated at the side of the uterus, and an avascular space is identified between these vessels and the uterus.

FIGURE 17–3 A Mersilene strap is placed under the vessels via a needle or carrier and brought out posteriorly above the uterosacral ligaments.

FIGURE 17–4 The Mersilene is tied anteriorly and closes the cervix. The operator’s finger in the cervix determines the tightness of the suture. The Mersilene is then suture-anchored with 3-0 Vicryl to the uterine wall to prevent slippage. The peritoneum is replaced between the bladder and the uterus and closed with a 3-0 running Vicryl stitch.

FIGURE 17–5 The posterior portion of the strap is sutured to the uterine wall with 3-0 Vicryl and the rectouterine peritoneum is replaced. It is sutured closed with a running 3-0 Vicryl suture.