Abdomen

Conceptual overview

General description

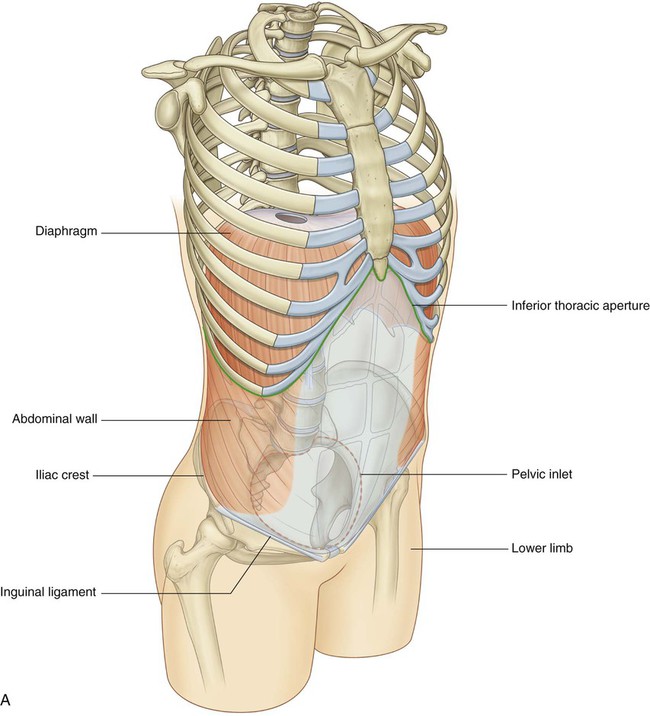

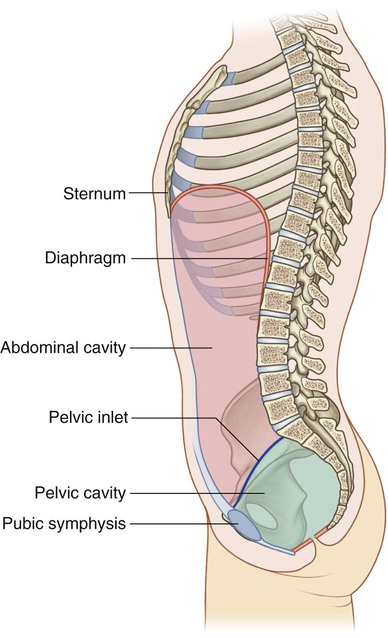

The abdomen is a roughly cylindrical chamber extending from the inferior margin of the thorax to the superior margin of the pelvis and the lower limb (Fig. 4.1A).

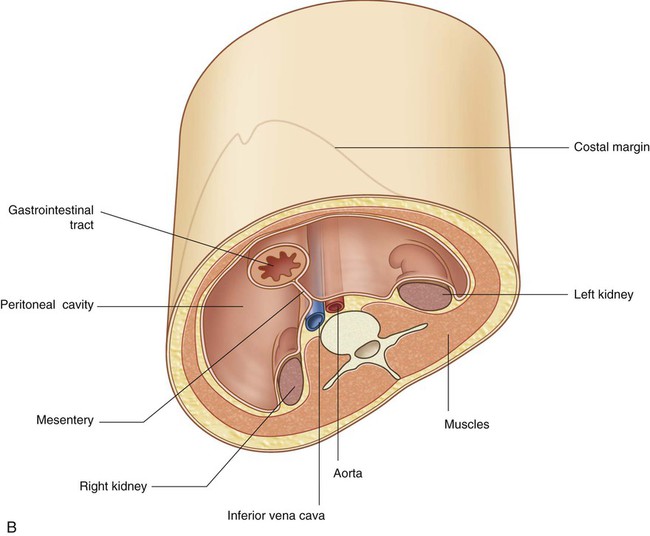

Abdominal viscera are either suspended in the peritoneal cavity by mesenteries or positioned between the cavity and the musculoskeletal wall (Fig. 4.1B).

major elements of the gastrointestinal system—the caudal end of the esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder;

major elements of the gastrointestinal system—the caudal end of the esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder;

Functions

Houses and protects major viscera

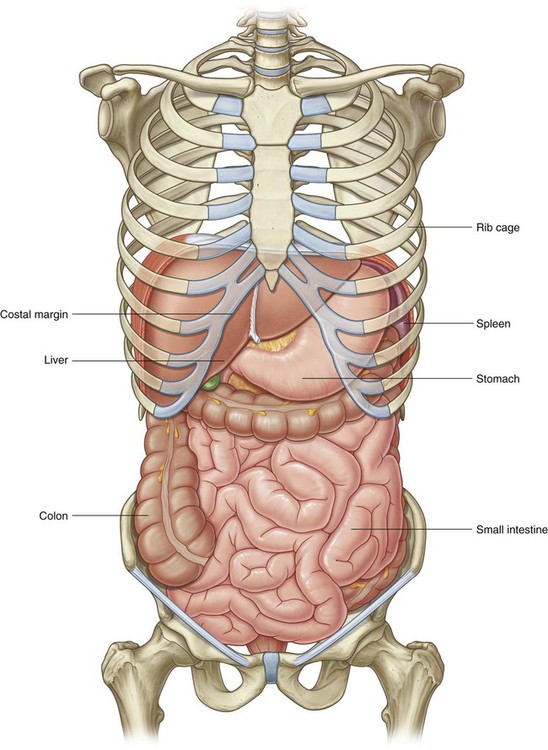

The abdomen houses major elements of the gastrointestinal system (Fig. 4.2), the spleen, and parts of the urinary system.

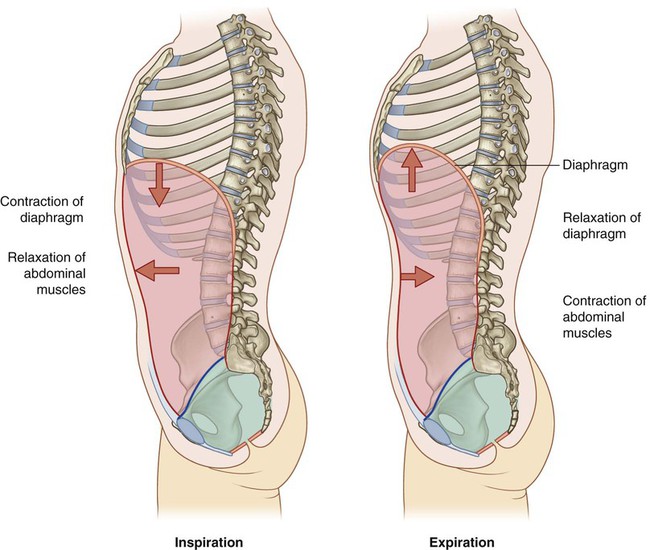

Breathing

One of the most important roles of the abdominal wall is to assist in breathing:

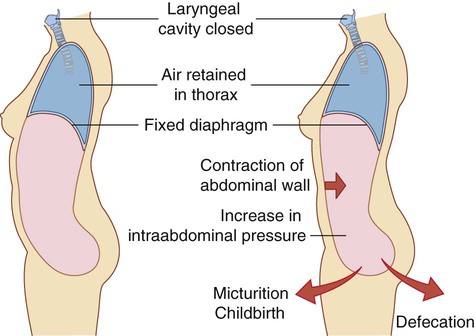

Changes in intraabdominal pressure

Contraction of abdominal wall muscles can dramatically increase intraabdominal pressure when the diaphragm is in a fixed position (Fig. 4.4). Air is retained in the lungs by closing valves in the larynx in the neck. Increased intra-abdominal pressure assists in voiding the contents of the bladder and rectum and in giving birth.

Component parts

Wall

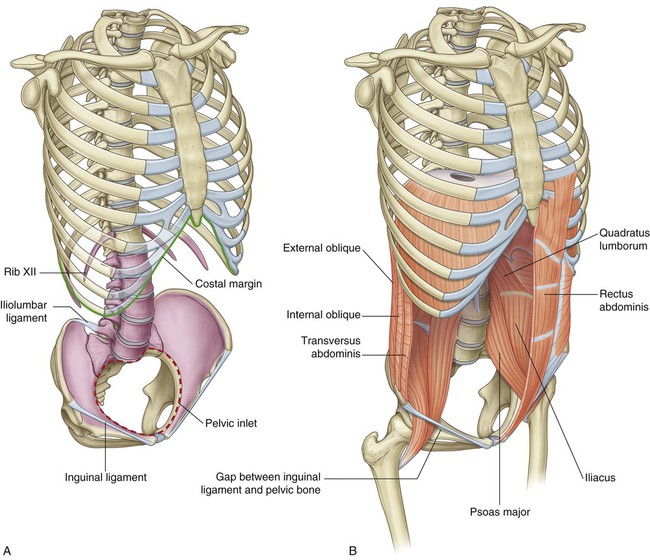

The abdominal wall consists partly of bone but mainly of muscle (Fig. 4.5). The skeletal elements of the wall (Fig. 4.5A) are:

the five lumbar vertebrae and their intervening intervertebral discs,

the five lumbar vertebrae and their intervening intervertebral discs,

the superior expanded parts of the pelvic bones, and

the superior expanded parts of the pelvic bones, and

bony components of the inferior thoracic wall, including the costal margin, rib XII, the end of rib XI, and the xiphoid process.

bony components of the inferior thoracic wall, including the costal margin, rib XII, the end of rib XI, and the xiphoid process.

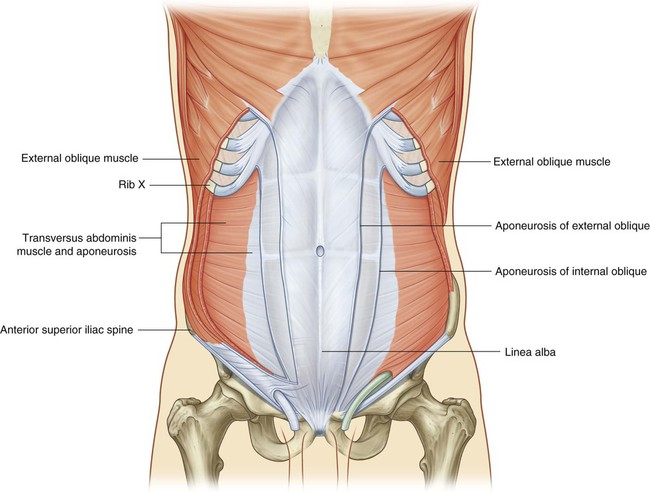

Muscles make up the rest of the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.5B):

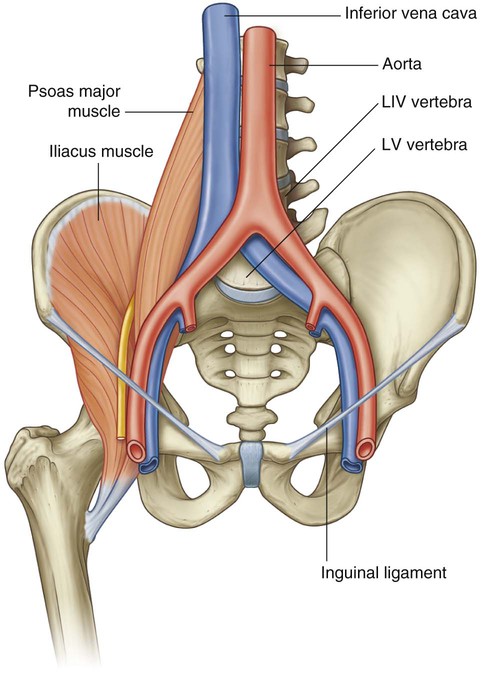

Lateral to the vertebral column, the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and iliacus muscles reinforce the posterior aspect of the wall. The distal ends of the psoas major and iliacus muscles pass into the thigh and are major flexors of the hip joint.

Lateral to the vertebral column, the quadratus lumborum, psoas major, and iliacus muscles reinforce the posterior aspect of the wall. The distal ends of the psoas major and iliacus muscles pass into the thigh and are major flexors of the hip joint.

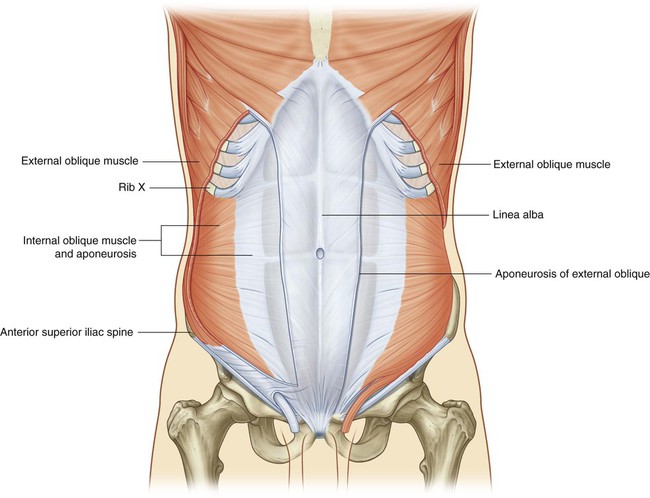

Lateral parts of the abdominal wall are predominantly formed by three layers of muscles, which are similar in orientation to the intercostal muscles of the thorax—transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique.

Lateral parts of the abdominal wall are predominantly formed by three layers of muscles, which are similar in orientation to the intercostal muscles of the thorax—transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique.

Anteriorly, a segmented muscle (the rectus abdominis) on each side spans the distance between the inferior thoracic wall and the pelvis.

Anteriorly, a segmented muscle (the rectus abdominis) on each side spans the distance between the inferior thoracic wall and the pelvis.

Abdominal cavity

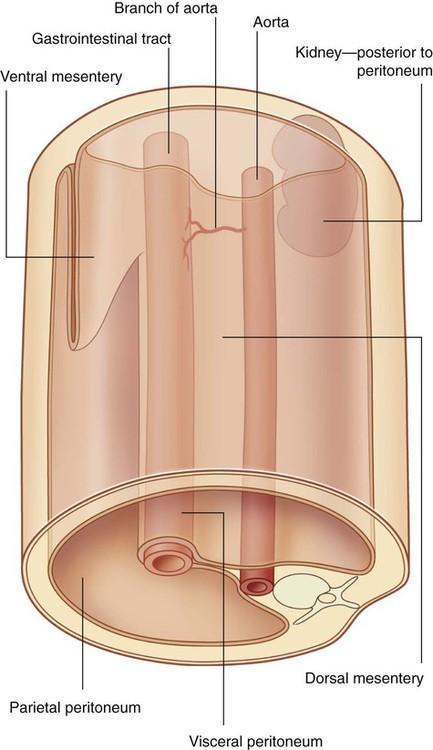

The general organization of the abdominal cavity is one in which a central gut tube (gastrointestinal system) is suspended from the posterior abdominal wall and partly from the anterior abdominal wall by thin sheets of tissue (mesenteries; Fig. 4.6):

a ventral (anterior) mesentery for proximal regions of the gut tube;

a ventral (anterior) mesentery for proximal regions of the gut tube;

a dorsal (posterior) mesentery along the entire length of the system.

a dorsal (posterior) mesentery along the entire length of the system.

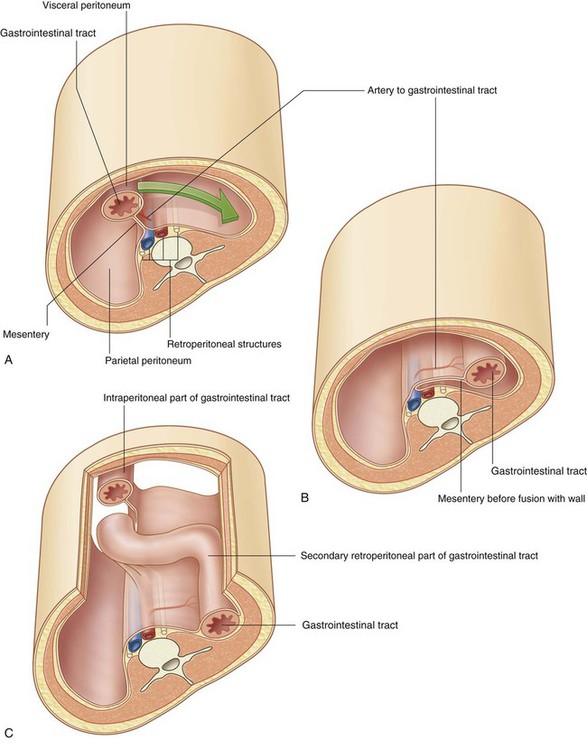

Abdominal viscera are either intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal:

Intraperitoneal structures, such as elements of the gastrointestinal system, are suspended from the abdominal wall by mesenteries;

Intraperitoneal structures, such as elements of the gastrointestinal system, are suspended from the abdominal wall by mesenteries;

Structures that are not suspended in the abdominal cavity by a mesentery and that lie between the parietal peritoneum and abdominal wall are retroperitoneal in position.

Structures that are not suspended in the abdominal cavity by a mesentery and that lie between the parietal peritoneum and abdominal wall are retroperitoneal in position.

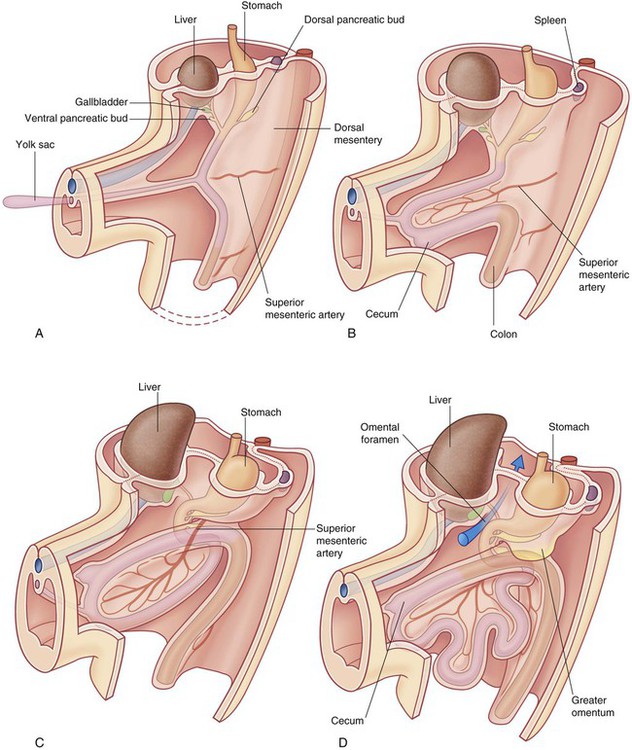

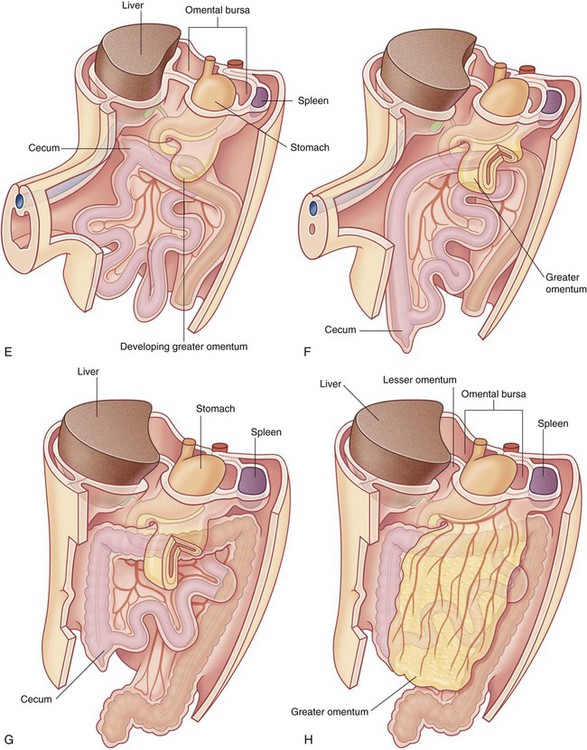

During development, some organs, such as parts of the small and large intestines, are suspended initially in the abdominal cavity by a mesentery, and later become retroperitoneal secondarily by fusing with the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.7).

Inferior thoracic aperture

The superior aperture of the abdomen is the inferior thoracic aperture, which is closed by the diaphragm (see pp. 126-127). The margin of the inferior thoracic aperture consists of vertebra TXII, rib XII, the distal end of rib XI, the costal margin, and the xiphoid process of the sternum.

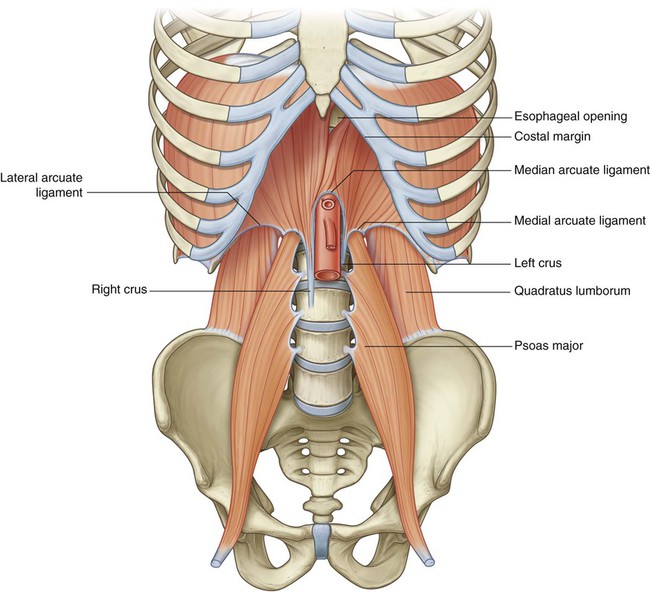

Diaphragm

The musculotendinous diaphragm separates the abdomen from the thorax.

The diaphragm attaches to the margin of the inferior thoracic aperture, but the attachment is complex posteriorly and extends into the lumbar area of the vertebral column (Fig. 4.8). On each side, a muscular extension (crus) firmly anchors the diaphragm to the anterolateral surface of the vertebral column as far down as vertebra LIII on the right and vertebra LII on the left.

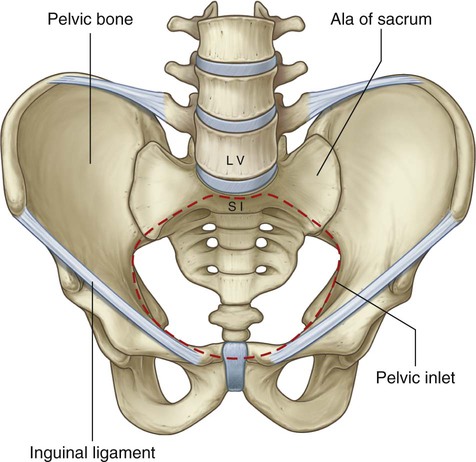

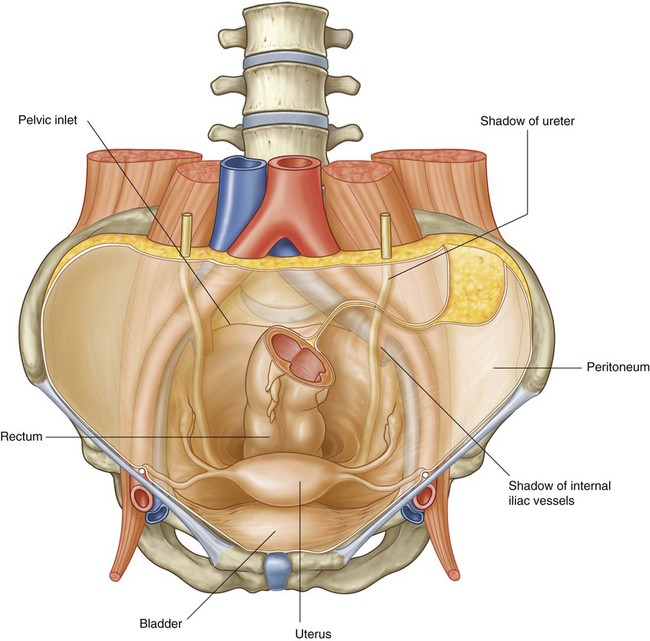

Pelvic inlet

The circular margin of the pelvic inlet is formed entirely by bone:

anteriorly by the pubic symphysis, and

anteriorly by the pubic symphysis, and

laterally, on each side, by a distinct bony rim on the pelvic bone (Fig. 4.9).

laterally, on each side, by a distinct bony rim on the pelvic bone (Fig. 4.9).

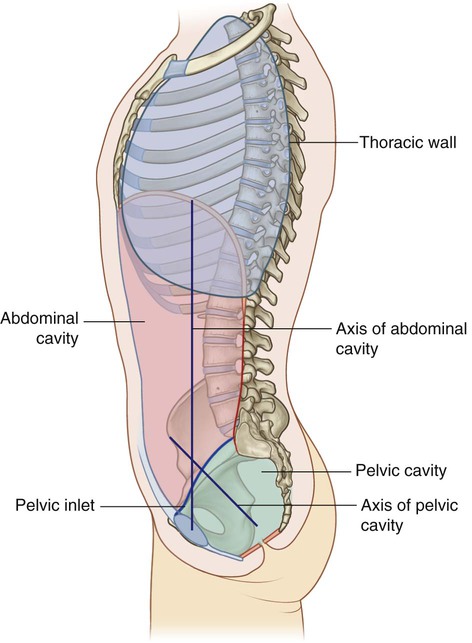

Because of the way in which the sacrum and attached pelvic bones are angled posteriorly on the vertebral column, the pelvic cavity is not oriented in the same vertical plane as the abdominal cavity. Instead, the pelvic cavity projects posteriorly, and the inlet opens anteriorly and somewhat superiorly (Fig. 4.10).

Relationship to other regions

Thorax

The abdomen is separated from the thorax by the diaphragm. Structures pass between the two regions through or posterior to the diaphragm (see Fig. 4.8).

Lower limb

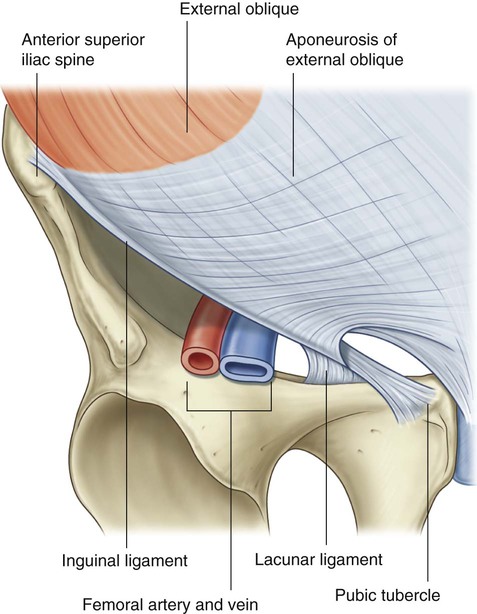

The abdomen communicates directly with the thigh through an aperture formed anteriorly between the inferior margin of the abdominal wall (marked by the inguinal ligament) and the pelvic bone (Fig. 4.12). Structures that pass through this aperture are:

Key features

Arrangement of abdominal viscera in the adult

A basic knowledge of the development of the gastrointestinal tract is needed to understand the arrangement of viscera and mesenteries in the abdomen (Fig. 4.13).

Superiorly, the dorsal and ventral mesenteries are anchored to the diaphragm.

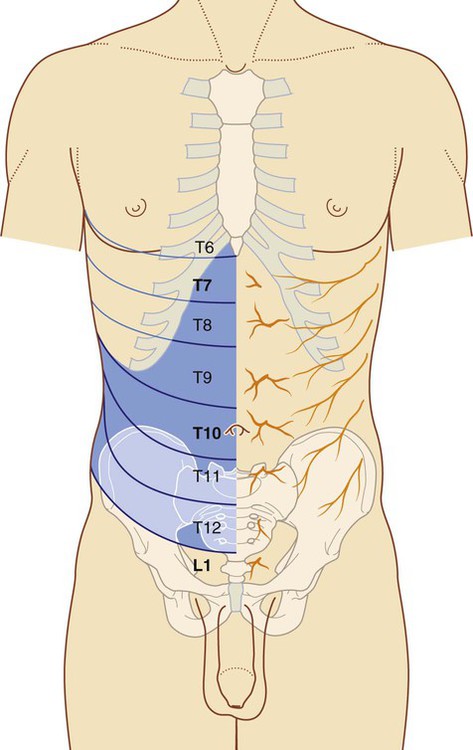

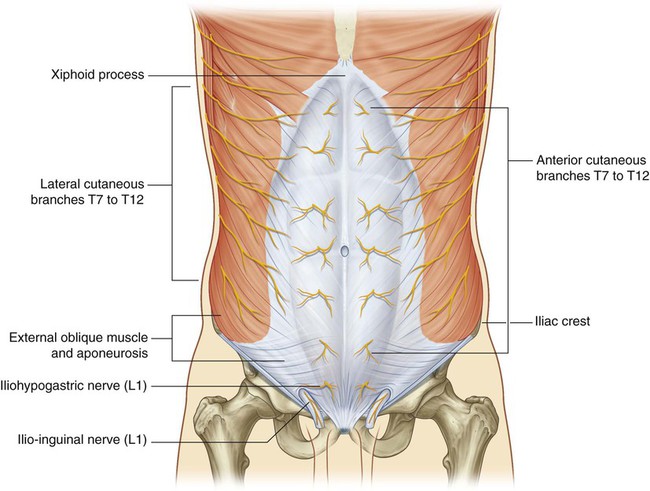

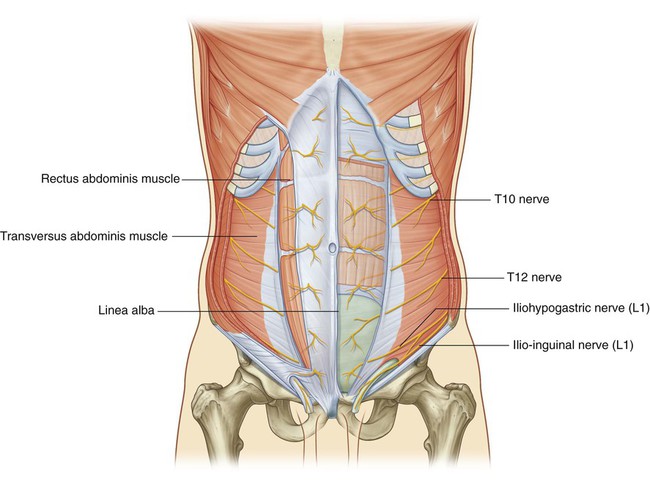

Skin and muscles of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall and thoracic intercostal nerves

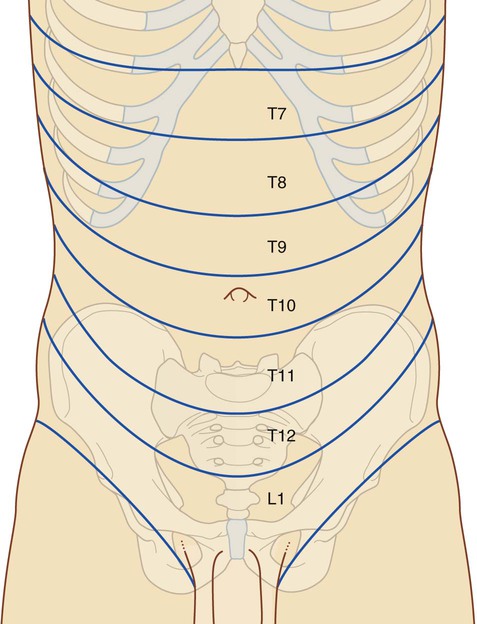

The anterior rami of thoracic spinal nerves T7 to T12 follow the inferior slope of the lateral parts of the ribs and cross the costal margin to enter the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.14). Intercostal nerves T7 to T11 supply skin and muscle of the abdominal wall, as does the subcostal nerve T12. In addition, T5 and T6 supply upper parts of the external oblique muscle of the abdominal wall; T6 also supplies cutaneous innervation to skin over the xiphoid.

Dermatomes of the anterior abdominal wall are indicated in Figure 4.14. In the midline, skin over the infrasternal angle is T6 and that around the umbilicus is T10. L1 innervates skin in the inguinal and suprapubic regions.

The groin is a weak area in the anterior abdominal wall

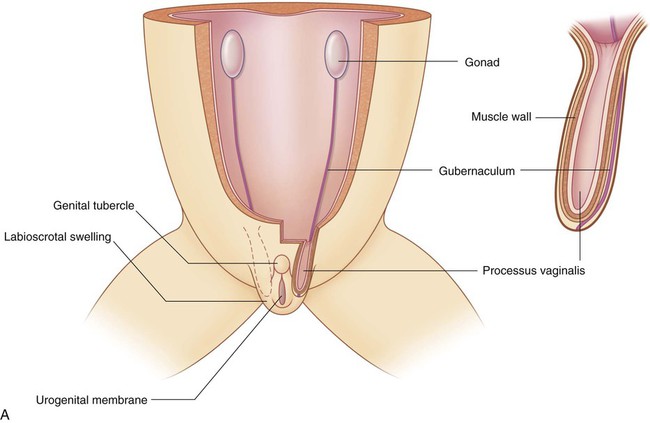

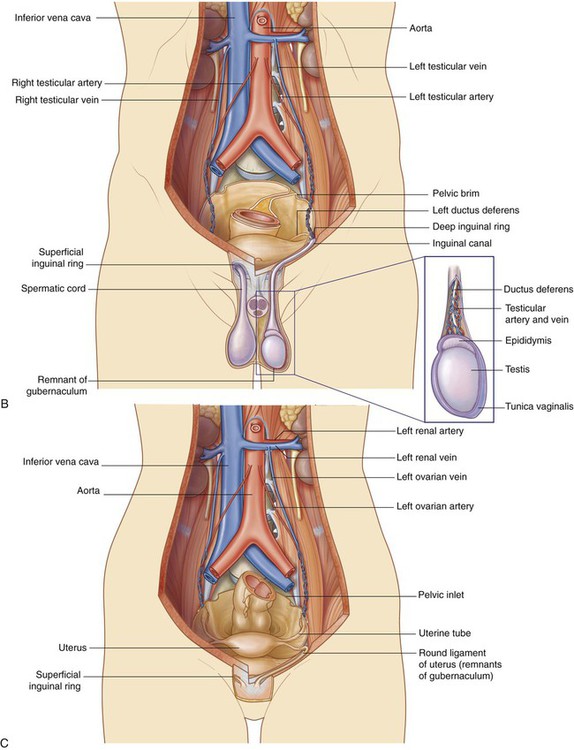

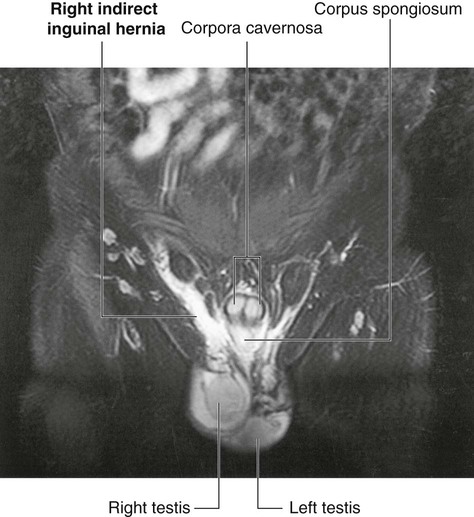

During development, the gonads in both sexes descend from their sites of origin on the posterior abdominal wall into the pelvic cavity in women and the developing scrotum in men (Fig. 4.15).

In both men and women, the groin (inguinal region) is a weak area in the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.15) and is the site of inguinal hernias.

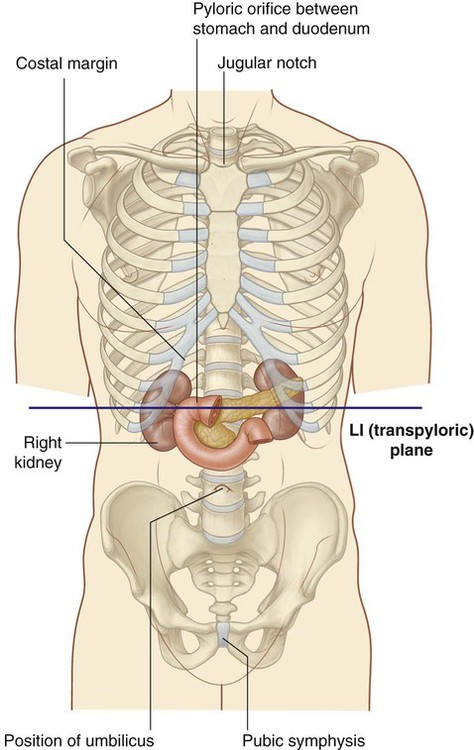

Vertebral level LI

The transpyloric plane is a horizontal plane that transects the body through the lower aspect of vertebra LI (Fig. 4.16). It:

is about midway between the jugular notch and the pubic symphysis, and crosses the costal margin on each side at roughly the ninth costal cartilage;

is about midway between the jugular notch and the pubic symphysis, and crosses the costal margin on each side at roughly the ninth costal cartilage;

crosses through the opening of the stomach into the duodenum (the pyloric orifice), which is just to the right of the body of LI; the duodenum then makes a characteristic C-shaped loop on the posterior abdominal wall and crosses the midline to open into the jejunum just to the left of the body of vertebra LII, whereas the head of the pancreas is enclosed by the loop of the duodenum, and the body of the pancreas extends across the midline to the left;

crosses through the opening of the stomach into the duodenum (the pyloric orifice), which is just to the right of the body of LI; the duodenum then makes a characteristic C-shaped loop on the posterior abdominal wall and crosses the midline to open into the jejunum just to the left of the body of vertebra LII, whereas the head of the pancreas is enclosed by the loop of the duodenum, and the body of the pancreas extends across the midline to the left;

crosses through the body of the pancreas; and

crosses through the body of the pancreas; and

approximates the position of the hila of the kidneys; though because the left kidney is slightly higher than the right, the transpyloric plane crosses through the inferior aspect of the left hilum and the superior part of the right hilum.

approximates the position of the hila of the kidneys; though because the left kidney is slightly higher than the right, the transpyloric plane crosses through the inferior aspect of the left hilum and the superior part of the right hilum.

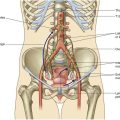

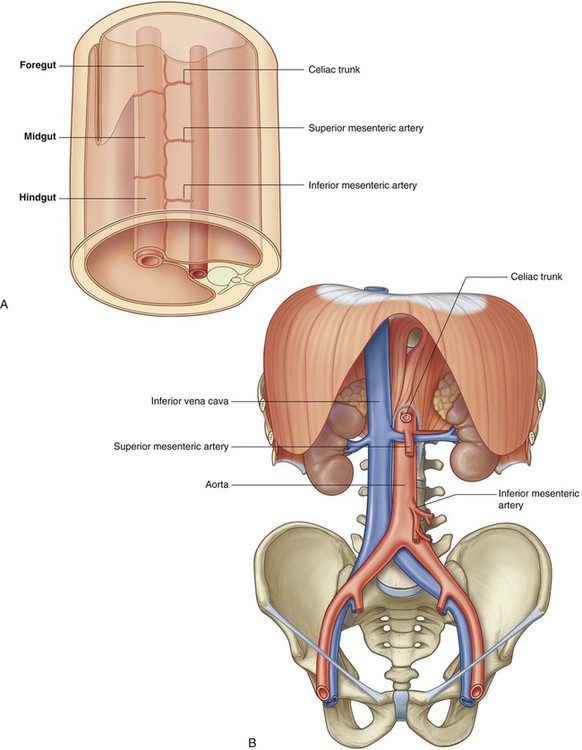

The gastrointestinal system and its derivatives are supplied by three major arteries

Three large unpaired arteries branch from the anterior surface of the abdominal aorta to supply the abdominal part of the gastrointestinal tract and all of the structures (liver, pancreas, and gallbladder) to which this part of the gut gives rise during development (Fig. 4.17). These arteries pass through derivatives of the dorsal and ventral mesenteries to reach the target viscera. These vessels therefore also supply structures such as the spleen and lymph nodes that develop in the mesenteries. These three arteries are:

the celiac artery, which branches from the abdominal aorta at the upper border of vertebra LI and supplies the foregut;

the celiac artery, which branches from the abdominal aorta at the upper border of vertebra LI and supplies the foregut;

the superior mesenteric artery, which arises from the abdominal aorta at the lower border of vertebra LI and supplies the midgut; and

the superior mesenteric artery, which arises from the abdominal aorta at the lower border of vertebra LI and supplies the midgut; and

the inferior mesenteric artery, which branches from the abdominal aorta at approximately vertebral level LIII and supplies the hindgut.

the inferior mesenteric artery, which branches from the abdominal aorta at approximately vertebral level LIII and supplies the hindgut.

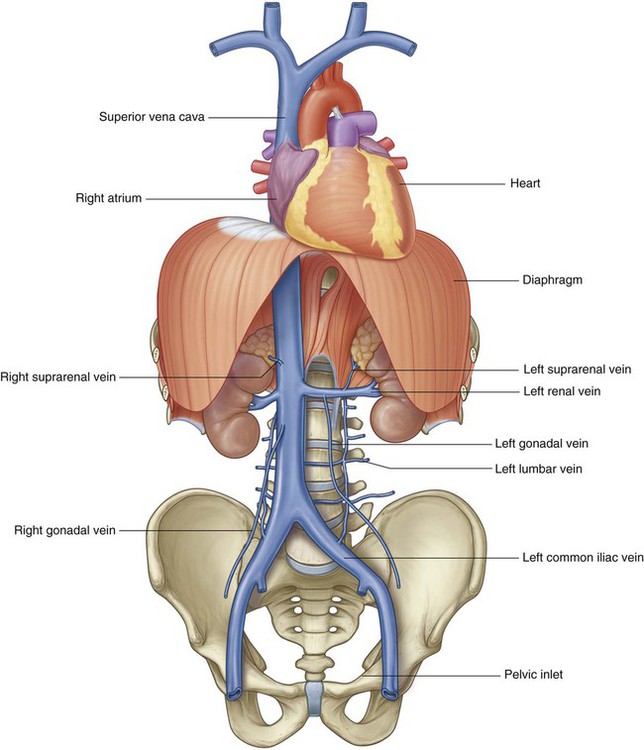

Venous shunts from left to right

All blood returning to the heart from regions of the body other than the lungs flows into the right atrium of the heart. The inferior vena cava is the major systemic vein in the abdomen and drains this region together with the pelvis, perineum, and both lower limbs (Fig. 4.18).

One of the most significant is the left renal vein, which drains the kidney, suprarenal gland, and gonad on the same side.

One of the most significant is the left renal vein, which drains the kidney, suprarenal gland, and gonad on the same side.

Another is the left common iliac vein, which crosses the midline at approximately vertebral level LV to join with its partner on the right to form the inferior vena cava. These veins drain the lower limbs, the pelvis, the perineum, and parts of the abdominal wall.

Another is the left common iliac vein, which crosses the midline at approximately vertebral level LV to join with its partner on the right to form the inferior vena cava. These veins drain the lower limbs, the pelvis, the perineum, and parts of the abdominal wall.

Other vessels crossing the midline include the left lumbar veins, which drain the back and posterior abdominal wall on the left side.

Other vessels crossing the midline include the left lumbar veins, which drain the back and posterior abdominal wall on the left side.

All venous drainage from the gastrointestinal system passes through the liver

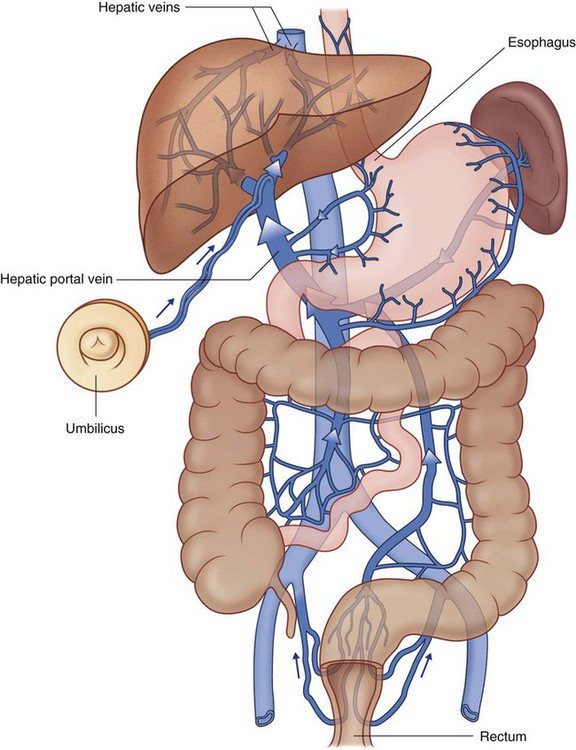

Blood from abdominal parts of the gastrointestinal system and the spleen passes through a second vascular bed, in the liver, before ultimately returning to the heart (Fig. 4.19).

Portacaval anastomoses

Other regions where portal and caval systems interconnect include:

where the liver is in direct contact with the diaphragm (the bare area of the liver);

where the liver is in direct contact with the diaphragm (the bare area of the liver);

where the wall of the gastrointestinal tract is in direct contact with the posterior abdominal wall (retroperitoneal areas of the large and small intestine); and

where the wall of the gastrointestinal tract is in direct contact with the posterior abdominal wall (retroperitoneal areas of the large and small intestine); and

the posterior surface of the pancreas (much of the pancreas is secondarily retroperitoneal).

the posterior surface of the pancreas (much of the pancreas is secondarily retroperitoneal).

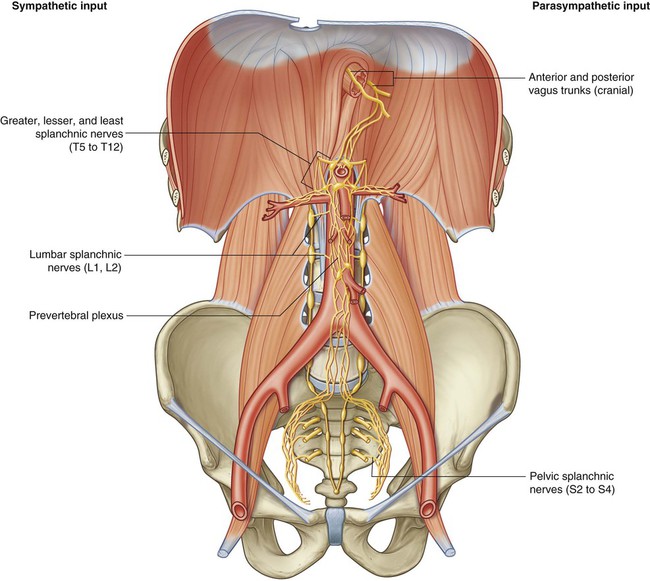

Abdominal viscera are supplied by a large prevertebral plexus

Innervation of the abdominal viscera is derived from a large prevertebral plexus associated mainly with the anterior and lateral surfaces of the aorta (Fig. 4.20). Branches are distributed to target tissues along vessels that originate from the abdominal aorta.

The prevertebral plexus contains sympathetic, parasympathetic, and visceral sensory components:

Regional anatomy

The abdomen is the part of the trunk inferior to the thorax (Fig. 4.21). Its musculomembranous walls surround a large cavity (the abdominal cavity), which is bounded superiorly by the diaphragm and inferiorly by the pelvic inlet.

Surface topography

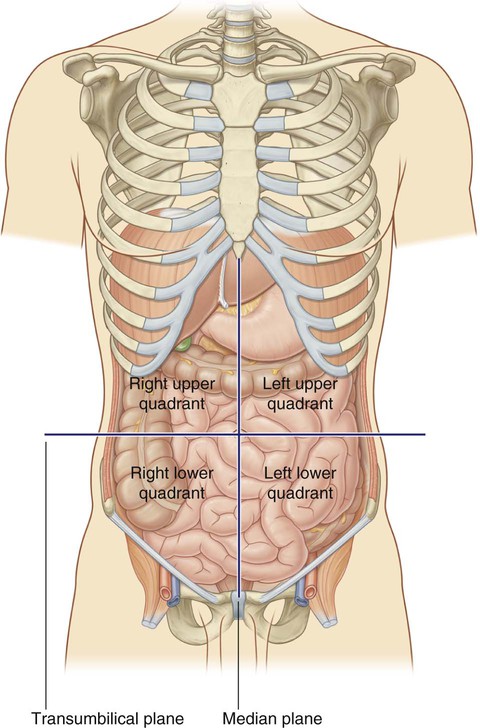

Four-quadrant pattern

A horizontal transumbilical plane passing through the umbilicus and the intervertebral disc between vertebrae LIII and LIV and intersecting with the vertical median plane divides the abdomen into four quadrants—the right upper, left upper, right lower, and left lower quadrants (Fig. 4.22).

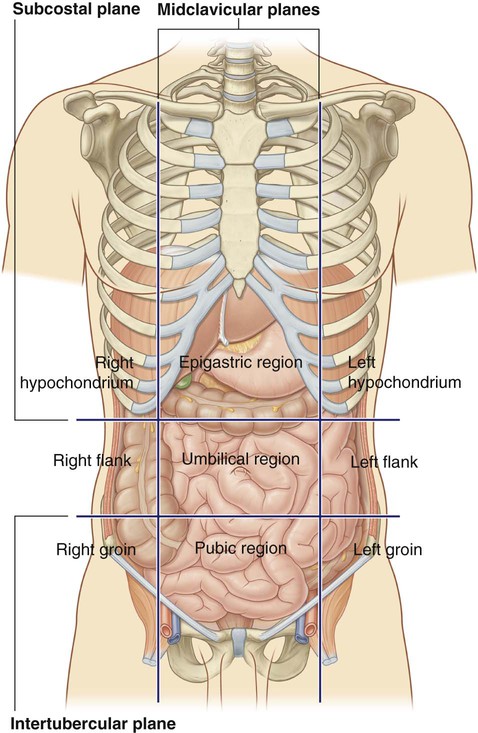

Nine-region pattern

The nine-region pattern is based on two horizontal and two vertical planes (Fig. 4.23).

The superior horizontal plane (the subcostal plane) is immediately inferior to the costal margins, which places it at the lower border of the costal cartilage of rib X and passing posteriorly through the body of vertebra LIII. (Note, however, that sometimes the transpyloric plane, halfway between the jugular notch and the symphysis pubis or halfway between the umbilicus and the inferior end of the body of the sternum, passing posteriorly through the lower border of vertebra LI and intersecting with the costal margin at the ends of the ninth costal cartilages, is used instead.)

The superior horizontal plane (the subcostal plane) is immediately inferior to the costal margins, which places it at the lower border of the costal cartilage of rib X and passing posteriorly through the body of vertebra LIII. (Note, however, that sometimes the transpyloric plane, halfway between the jugular notch and the symphysis pubis or halfway between the umbilicus and the inferior end of the body of the sternum, passing posteriorly through the lower border of vertebra LI and intersecting with the costal margin at the ends of the ninth costal cartilages, is used instead.)

The inferior horizontal plane (the intertubercular plane) connects the tubercles of the iliac crests, which are palpable structures 5 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spines, and passes through the upper part of the body of vertebra LV.

The inferior horizontal plane (the intertubercular plane) connects the tubercles of the iliac crests, which are palpable structures 5 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spines, and passes through the upper part of the body of vertebra LV.

The vertical planes pass from the midpoint of the clavicles inferiorly to a point midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic symphysis.

The vertical planes pass from the midpoint of the clavicles inferiorly to a point midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic symphysis.

These four planes establish the topographical divisions in the nine-region organization. The following designations are used for each region: superiorly the right hypochondrium, the epigastric region, and the left hypochondrium; inferiorly the right groin (inguinal region), pubic region, and left groin (inguinal region); and in the middle the right flank (lateral region), the umbilical region, and the left flank (lateral region) (Fig. 4.23).

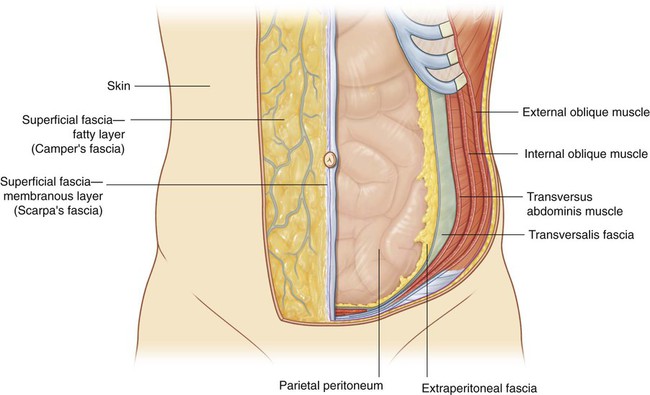

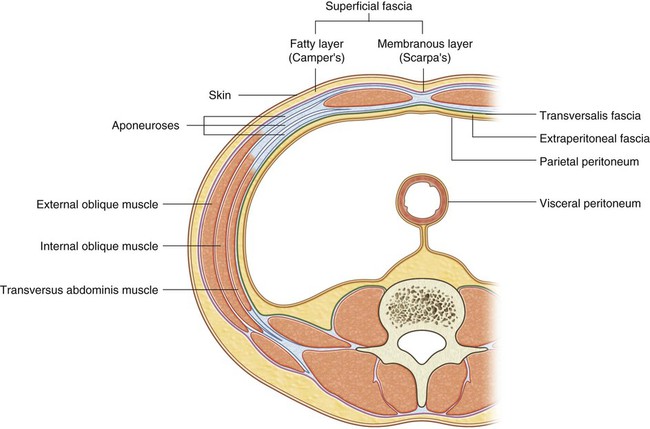

Abdominal wall

The abdominal wall covers a large area. It is bounded superiorly by the xiphoid process and costal margins, posteriorly by the vertebral column, and inferiorly by the upper parts of the pelvic bones. Its layers consist of skin, superficial fascia (subcutaneous tissue), muscles and their associated deep fascias, extraperitoneal fascia, and parietal peritoneum (Fig. 4.24).

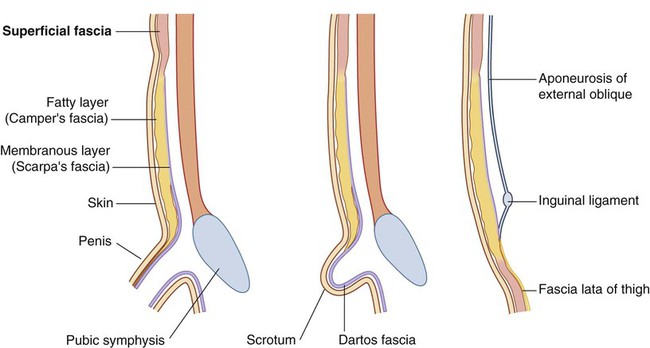

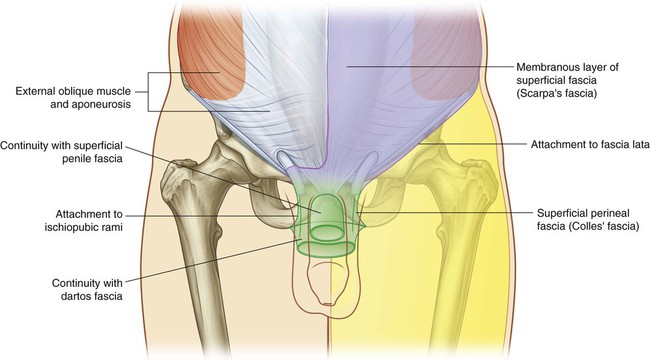

Superficial fascia

Deeper layer

The deeper membranous layer of superficial fascia (Scarpa’s fascia) is thin and membranous, and contains little or no fat (Fig. 4.25). Inferiorly, it continues into the thigh, but just below the inguinal ligament, it fuses with the deep fascia of the thigh (the fascia lata; Fig. 4.26). In the midline, it is firmly attached to the linea alba and the symphysis pubis. It continues into the anterior part of the perineum where it is firmly attached to the ischiopubic rami and to the posterior margin of the perineal membrane. Here, it is referred to as the superficial perineal fascia (Colles’ fascia).

In men, the deeper membranous layer of superficial fascia blends with the superficial layer as they both pass over the penis, forming the superficial fascia of the penis, before they continue into the scrotum where they form the dartos fascia (Fig. 4.25). Also in men, extensions of the deeper membranous layer of superficial fascia attached to the pubic symphysis pass inferiorly onto the dorsum and sides of the penis to form the fundiform ligament of penis. In women, the membranous layer of the superficial fascia continues into the labia majora and the anterior part of the perineum.

Anterolateral muscles

There are five muscles in the anterolateral group of abdominal wall muscles:

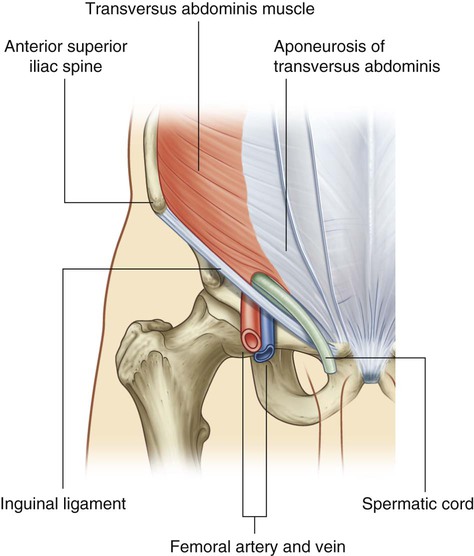

three flat muscles whose fibers begin posterolaterally, pass anteriorly, and are replaced by an aponeurosis as the muscle continues toward the midline—the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles;

three flat muscles whose fibers begin posterolaterally, pass anteriorly, and are replaced by an aponeurosis as the muscle continues toward the midline—the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles;

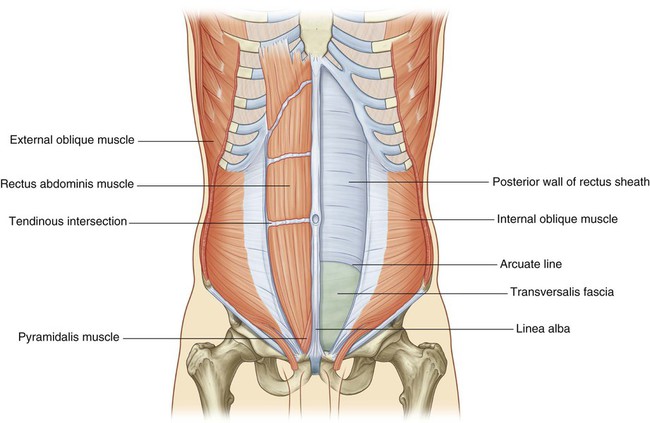

two vertical muscles, near the midline, which are enclosed within a tendinous sheath formed by the aponeuroses of the flat muscles—the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles.

two vertical muscles, near the midline, which are enclosed within a tendinous sheath formed by the aponeuroses of the flat muscles—the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles.

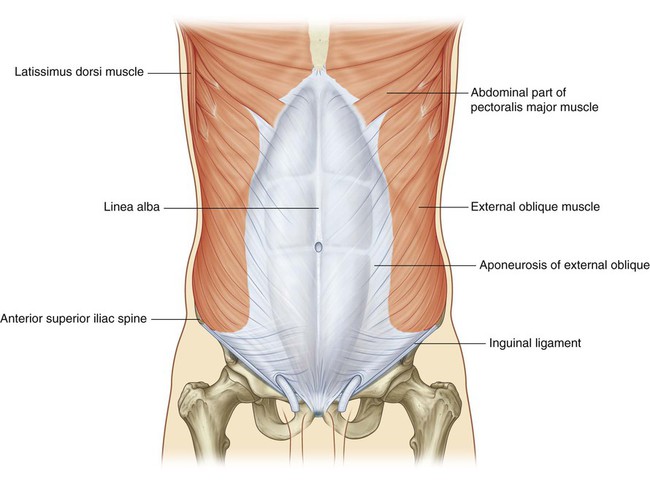

Flat muscles

External oblique

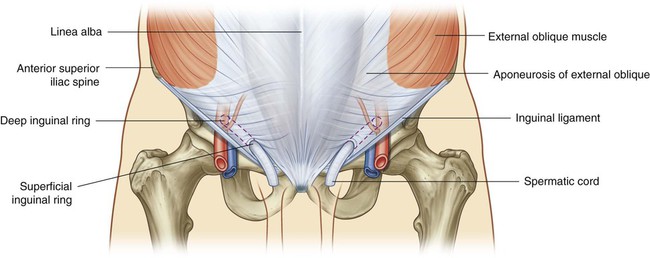

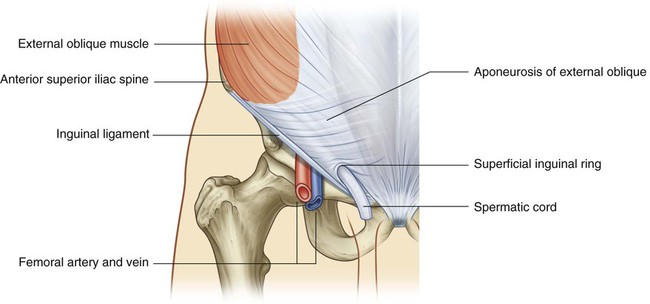

The most superficial of the three flat muscles in the anterolateral group of abdominal wall muscles is the external oblique, which is immediately deep to the superficial fascia (Fig. 4.27, Table 4.1). Its laterally placed muscle fibers pass in an inferomedial direction, while its large aponeurotic component covers the anterior part of the abdominal wall to the midline. Approaching the midline, the aponeuroses are entwined, forming the linea alba, which extends from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.

The lower border of the external oblique aponeurosis forms the inguinal ligament on each side (Fig. 4.27). This thickened reinforced free edge of the external oblique aponeurosis passes between the anterior superior iliac spine laterally and the pubic tubercle medially (Fig. 4.28). It folds under itself forming a trough, which plays an important role in the formation of the inguinal canal.

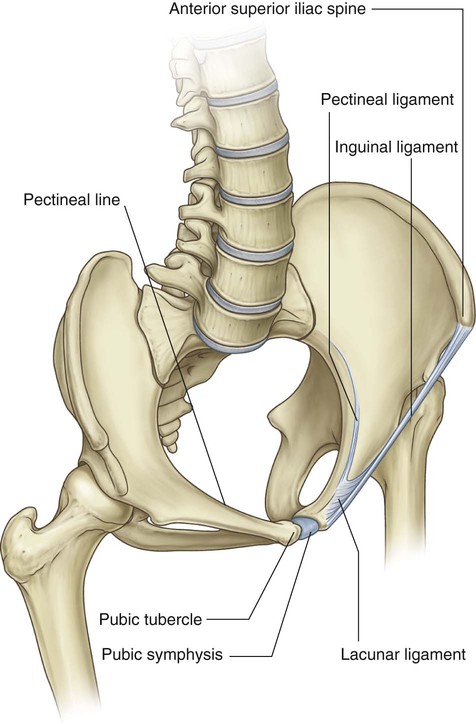

The lacunar ligament is a crescent-shaped extension of fibers at the medial end of the inguinal ligament that pass backward to attach to the pecten pubis on the superior ramus of the pubic bone (Figs. 4.28 and 4.29).

The lacunar ligament is a crescent-shaped extension of fibers at the medial end of the inguinal ligament that pass backward to attach to the pecten pubis on the superior ramus of the pubic bone (Figs. 4.28 and 4.29).

Additional fibers extend from the lacunar ligament along the pecten pubis of the pelvic brim to form the pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament.

Additional fibers extend from the lacunar ligament along the pecten pubis of the pelvic brim to form the pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament.

Internal oblique

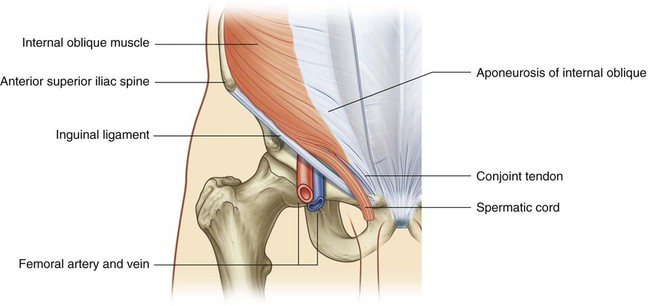

Deep to the external oblique muscle is the internal oblique muscle, which is the second of the three flat muscles (Fig. 4.30, Table 4.1). This muscle is smaller and thinner than the external oblique, with most of its muscle fibers passing in a superomedial direction. Its lateral muscular components end anteriorly as an aponeurosis that blends into the linea alba at the midline.

Vertical muscles

The two vertical muscles in the anterolateral group of abdominal wall muscles are the large rectus abdominis and the small pyramidalis (Fig. 4.32, Table 4.1).

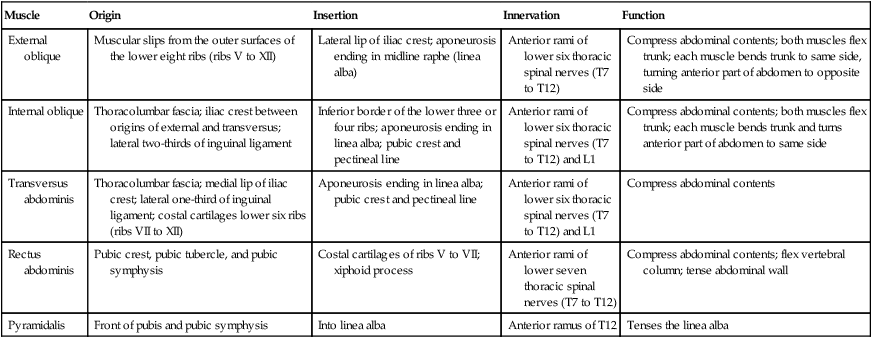

Table 4.1

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| External oblique | Muscular slips from the outer surfaces of the lower eight ribs (ribs V to XII) | Lateral lip of iliac crest; aponeurosis ending in midline raphe (linea alba) | Anterior rami of lower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T12) | Compress abdominal contents; both muscles flex trunk; each muscle bends trunk to same side, turning anterior part of abdomen to opposite side |

| Internal oblique | Thoracolumbar fascia; iliac crest between origins of external and transversus; lateral two-thirds of inguinal ligament | Inferior border of the lower three or four ribs; aponeurosis ending in linea alba; pubic crest and pectineal line | Anterior rami of lower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T12) and L1 | Compress abdominal contents; both muscles flex trunk; each muscle bends trunk and turns anterior part of abdomen to same side |

| Transversus abdominis | Thoracolumbar fascia; medial lip of iliac crest; lateral one-third of inguinal ligament; costal cartilages lower six ribs (ribs VII to XII) | Aponeurosis ending in linea alba; pubic crest and pectineal line | Anterior rami of lower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T12) and L1 | Compress abdominal contents |

| Rectus abdominis | Pubic crest, pubic tubercle, and pubic symphysis | Costal cartilages of ribs V to VII; xiphoid process | Anterior rami of lower seven thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T12) | Compress abdominal contents; flex vertebral column; tense abdominal wall |

| Pyramidalis | Front of pubis and pubic symphysis | Into linea alba | Anterior ramus of T12 | Tenses the linea alba |

Rectus abdominis

The rectus abdominis is a long, flat muscle and extends the length of the anterior abdominal wall. It is a paired muscle, separated in the midline by the linea alba, and it widens and thins as it ascends from the pubic symphysis to the costal margin. Along its course, it is intersected by three or four transverse fibrous bands or tendinous intersections (Fig. 4.32). These are easily visible on individuals with a well-developed rectus abdominis.

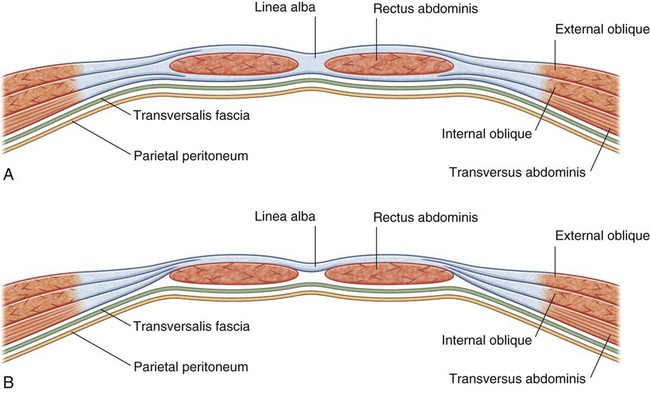

Rectus sheath

The rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles are enclosed in an aponeurotic tendinous sheath (the rectus sheath) formed by a unique layering of the aponeuroses of the external and internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles (Fig. 4.33).

The anterior wall consists of the aponeurosis of the external oblique and half of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique, which splits at the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis.

The anterior wall consists of the aponeurosis of the external oblique and half of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique, which splits at the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis.

The posterior wall of the rectus sheath consists of the other half of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis.

The posterior wall of the rectus sheath consists of the other half of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis.

At a point midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis, corresponding to the beginning of the lower one-quarter of the rectus abdominis muscle, all of the aponeuroses move anterior to the rectus muscle. There is no posterior wall of the rectus sheath and the anterior wall of the sheath consists of the aponeuroses of the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis muscles. From this point inferiorly, the rectus abdominis muscle is in direct contact with the transversalis fascia. Marking this point of transition is an arch of fibers (the arcuate line; see Fig. 4.32).

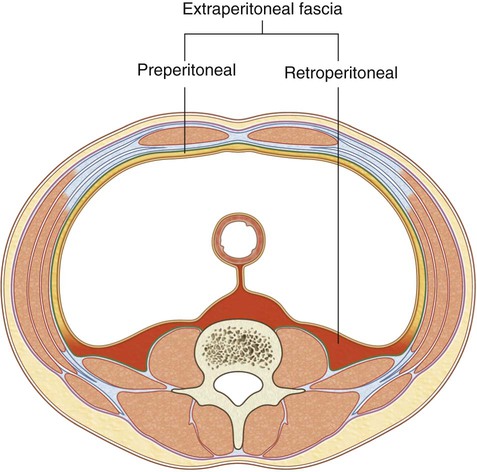

Extraperitoneal fascia

Deep to the transversalis fascia is a layer of connective tissue, the extraperitoneal fascia, which separates the transversalis fascia from the peritoneum (Fig. 4.34). Containing varying amounts of fat, this layer not only lines the abdominal cavity but is also continuous with a similar layer lining the pelvic cavity. It is abundant on the posterior abdominal wall, especially around the kidneys, continues over organs covered by peritoneal reflections, and, as the vasculature is located in this layer, extends into mesenteries with the blood vessels. Viscera in the extraperitoneal fascia are referred to as retroperitoneal.

In the description of specific surgical procedures, the terminology used to describe the extraperitoneal fascia is further modified. The fascia toward the anterior side of the body is described as preperitoneal (or, less commonly, properitoneal) and the fascia toward the posterior side of the body has been described as retroperitoneal (Fig. 4.35). Examples of the use of these terms would be the continuity of fat in the inguinal canal with the preperitoneal fat and a transabdominal preperitoneal laparoscopic repair of an inguinal hernia.

Peritoneum

Deep to the extraperitoneal fascia is the peritoneum (see Figs. 4.6 and 4.7 on pp. 260-261). This thin serous membrane lines the walls of the abdominal cavity and, at various points, reflects onto the abdominal viscera, providing either a complete or a partial covering. The peritoneum lining the walls is the parietal peritoneum; the peritoneum covering the viscera is the visceral peritoneum.

Innervation

The skin, muscles, and parietal peritoneum of the anterolateral abdominal wall are supplied by T7 to T12 and L1 spinal nerves. The anterior rami of these spinal nerves pass around the body, from posterior to anterior, in an inferomedial direction (Fig. 4.36). As they proceed, they give off a lateral cutaneous branch and end as an anterior cutaneous branch.

The intercostal nerves (T7 to T11) leave their intercostal spaces, passing deep to the costal cartilages, and continue onto the anterolateral abdominal wall between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles (Fig. 4.37). Reaching the lateral edge of the rectus sheath, they enter the rectus sheath and pass posterior to the lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle. Approaching the midline, an anterior cutaneous branch passes through the rectus abdominis muscle and the anterior wall of the rectus sheath to supply the skin.

Nerves T7 to T9 supply the skin from the xiphoid process to just above the umbilicus.

Nerves T7 to T9 supply the skin from the xiphoid process to just above the umbilicus.

T10 supplies the skin around the umbilicus.

T10 supplies the skin around the umbilicus.

T11, T12, and L1 supply the skin from just below the umbilicus to, and including, the pubic region (Fig. 4.38).

T11, T12, and L1 supply the skin from just below the umbilicus to, and including, the pubic region (Fig. 4.38).

Additionally, the ilio-inguinal nerve (a branch of L1) supplies the anterior surface of the scrotum or labia majora, and sends a small cutaneous branch to the thigh.

Additionally, the ilio-inguinal nerve (a branch of L1) supplies the anterior surface of the scrotum or labia majora, and sends a small cutaneous branch to the thigh.

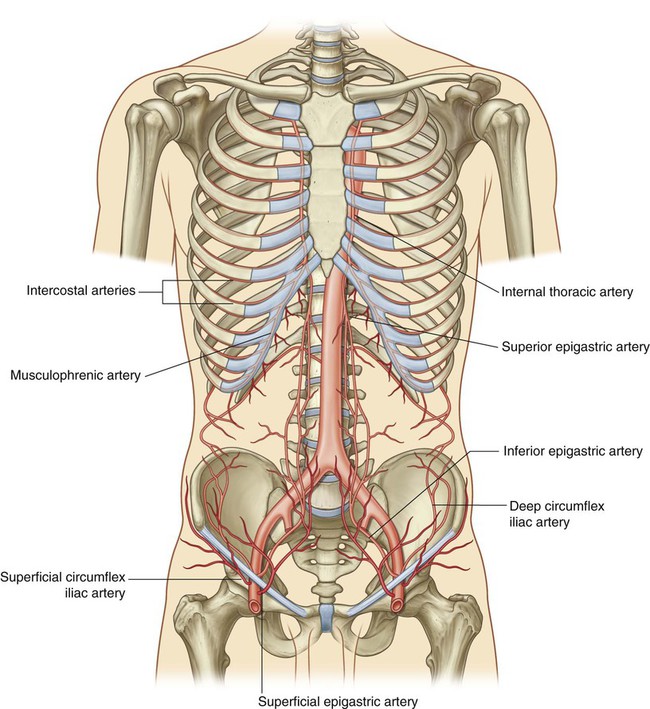

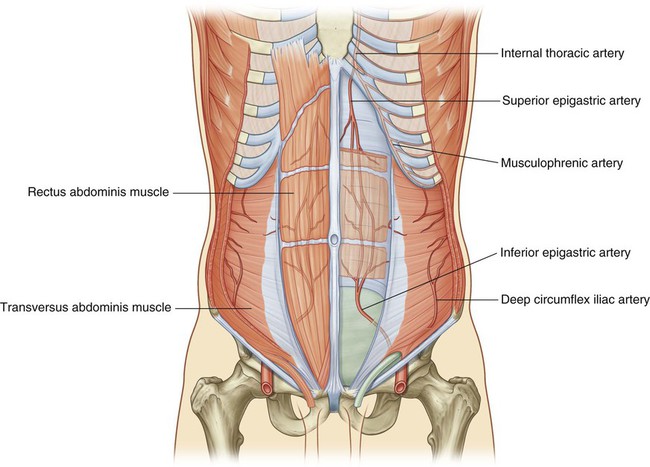

Arterial supply and venous drainage

Numerous blood vessels supply the anterolateral abdominal wall. Superficially:

the superior part of the wall is supplied by branches from the musculophrenic artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery, and

the superior part of the wall is supplied by branches from the musculophrenic artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery, and

the inferior part of the wall is supplied by the medially placed superficial epigastric artery and the laterally placed superficial circumflex iliac artery, both branches of the femoral artery (Fig. 4.39).

the inferior part of the wall is supplied by the medially placed superficial epigastric artery and the laterally placed superficial circumflex iliac artery, both branches of the femoral artery (Fig. 4.39).

At a deeper level:

the superior part of the wall is supplied by the superior epigastric artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery;

the superior part of the wall is supplied by the superior epigastric artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery;

the lateral part of the wall is supplied by branches of the tenth and eleventh intercostal arteries and the subcostal artery; and

the lateral part of the wall is supplied by branches of the tenth and eleventh intercostal arteries and the subcostal artery; and

the inferior part of the wall is supplied by the medially placed inferior epigastric artery and the laterally placed deep circumflex iliac artery, both branches of the external iliac artery.

the inferior part of the wall is supplied by the medially placed inferior epigastric artery and the laterally placed deep circumflex iliac artery, both branches of the external iliac artery.

The superior and inferior epigastric arteries both enter the rectus sheath. They are posterior to the rectus abdominis muscle throughout their course, and anastomose with each other (Fig. 4.40).

Veins of similar names follow the arteries and are responsible for venous drainage.

Lymphatic drainage

Superficial lymphatics above the umbilicus pass in a superior direction to the axillary nodes, while drainage below the umbilicus passes in an inferior direction to the superficial inguinal nodes.

Superficial lymphatics above the umbilicus pass in a superior direction to the axillary nodes, while drainage below the umbilicus passes in an inferior direction to the superficial inguinal nodes.

Deep lymphatic drainage follows the deep arteries back to parasternal nodes along the internal thoracic artery, lumbar nodes along the abdominal aorta, and external iliac nodes along the external iliac artery.

Deep lymphatic drainage follows the deep arteries back to parasternal nodes along the internal thoracic artery, lumbar nodes along the abdominal aorta, and external iliac nodes along the external iliac artery.

Groin

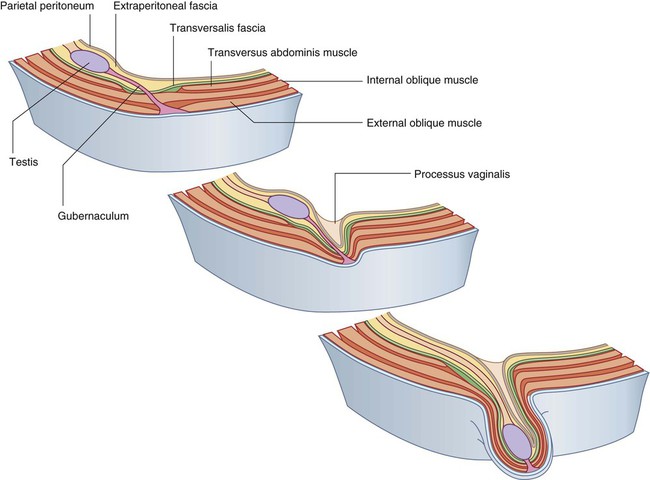

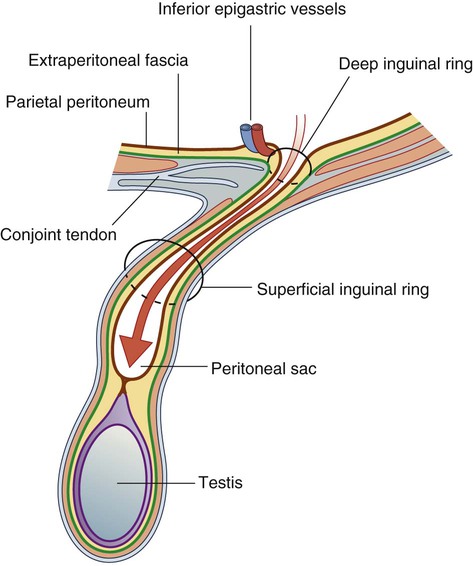

The inherent weakness in the anterior abdominal wall in the groin is caused by changes that occur during the development of the gonads. Before the descent of the testes and ovaries from their initial position high in the posterior abdominal wall, a peritoneal outpouching (the processus vaginalis) forms (Fig. 4.41), protruding through the various layers of the anterior abdominal wall and acquiring coverings from each:

The transversalis fascia forms its deepest covering.

The transversalis fascia forms its deepest covering.

The second covering is formed by the musculature of the internal oblique (a covering from the transversus abdominis muscle is not acquired because the processus vaginalis passes under the arching fibers of this abdominal wall muscle).

The second covering is formed by the musculature of the internal oblique (a covering from the transversus abdominis muscle is not acquired because the processus vaginalis passes under the arching fibers of this abdominal wall muscle).

Its most superficial covering is the aponeurosis of the external oblique.

Its most superficial covering is the aponeurosis of the external oblique.

The final event in this development is the descent of the testes into the scrotum or of the ovaries into the pelvic cavity. This process depends on the development of the gubernaculum, which extends from the inferior border of the developing gonad to the labioscrotal swellings (Fig. 4.41).

The processus vaginalis is immediately anterior to the gubernaculum within the inguinal canal.

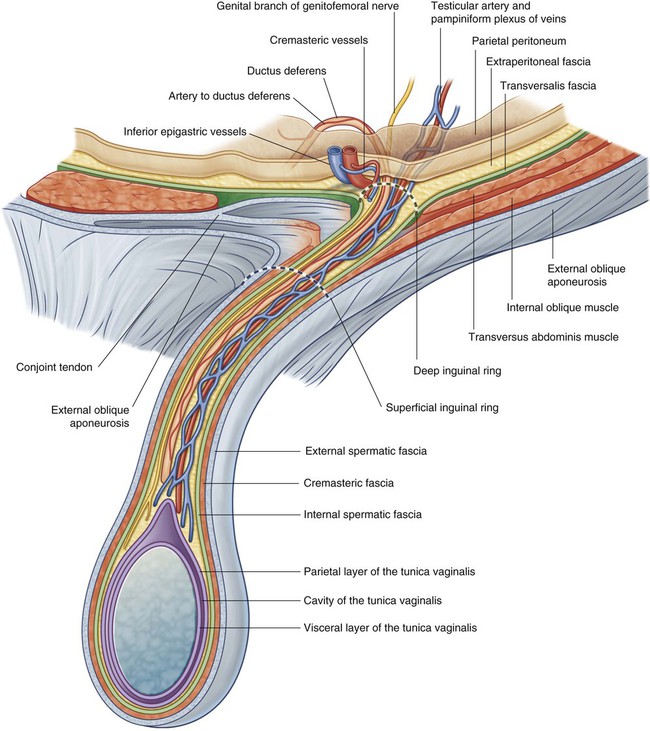

Inguinal canal

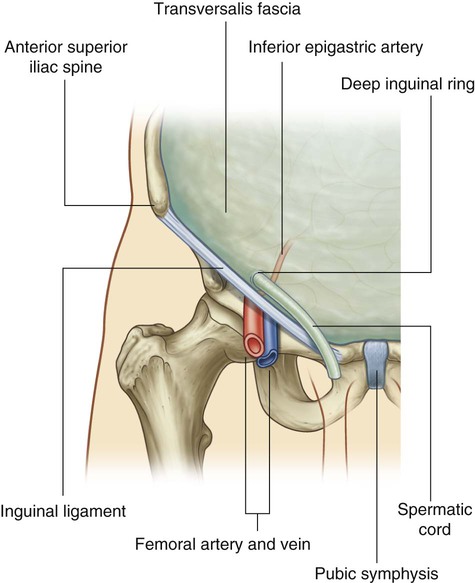

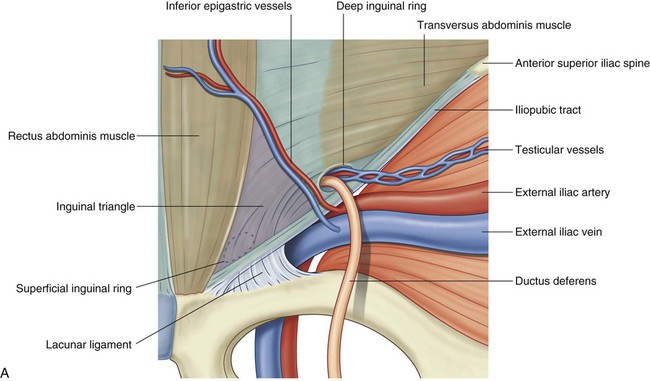

The inguinal canal is a slit-like passage that extends in a downward and medial direction, just above and parallel to the lower half of the inguinal ligament. It begins at the deep inguinal ring and continues for approximately 4 cm, ending at the superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 4.42). The contents of the canal are the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, the spermatic cord in men, and the round ligament of the uterus in women. Additionally, in both sexes, the ilio-inguinal nerve passes through part of the canal, exiting through the superficial inguinal ring with the other contents.

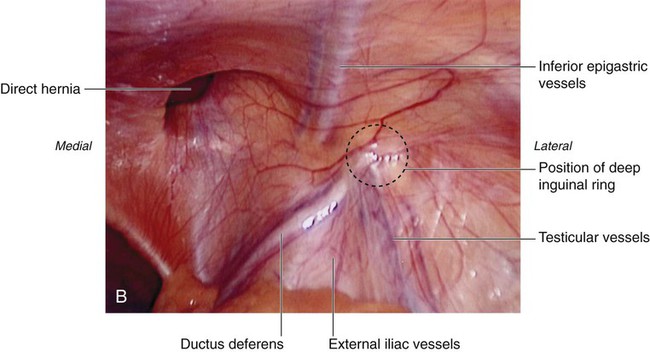

Deep inguinal ring

The deep (internal) inguinal ring is the beginning of the inguinal canal and is at a point midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis (Fig. 4.43). It is just above the inguinal ligament and immediately lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. Although sometimes referred to as a defect or opening in the transversalis fascia, it is actually the beginning of the tubular evagination of transversalis fascia that forms one of the coverings (the internal spermatic fascia) of the spermatic cord in men or the round ligament of the uterus in women.

Superficial inguinal ring

The superficial (external) inguinal ring is the end of the inguinal canal and is superior to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 4.44). It is a triangular opening in the aponeurosis of the external oblique, with its apex pointing superolaterally and its base formed by the pubic crest. The two remaining sides of the triangle (the medial crus and the lateral crus) are attached to the pubic symphysis and the pubic tubercle, respectively. At the apex of the triangle the two crura are held together by crossing (intercrural) fibers, which prevent further widening of the superficial ring.

Anterior wall

The anterior wall of the inguinal canal is formed along its entire length by the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle (Fig. 4.44). It is also reinforced laterally by the lower fibers of the internal oblique that originate from the lateral two-thirds of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 4.45). This adds an additional covering over the deep inguinal ring, which is a potential point of weakness in the anterior abdominal wall. Furthermore, as the internal oblique muscle covers the deep inguinal ring, it also contributes a layer (the cremasteric fascia containing the cremasteric muscle) to the coverings of the structures traversing the inguinal canal.

Posterior wall

The posterior wall of the inguinal canal is formed along its entire length by the transversalis fascia (see Fig. 4.43). It is reinforced along its medial one-third by the conjoint tendon (inguinal falx; Fig. 4.45). This tendon is the combined insertion of the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles into the pubic crest and pectineal line.

Spermatic cord

The spermatic cord begins to form proximally at the deep inguinal ring and consists of structures passing between the abdominopelvic cavities and the testis, and the three fascial coverings that enclose these structures (Fig. 4.47).

The structures in the spermatic cord include:

the artery to the ductus deferens (from the inferior vesical artery),

the artery to the ductus deferens (from the inferior vesical artery),

the testicular artery (from the abdominal aorta),

the testicular artery (from the abdominal aorta),

the pampiniform plexus of veins (testicular veins),

the pampiniform plexus of veins (testicular veins),

the cremasteric artery and vein (small vessels associated with the cremasteric fascia),

the cremasteric artery and vein (small vessels associated with the cremasteric fascia),

the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (innervation to the cremasteric muscle),

the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (innervation to the cremasteric muscle),

Three fascias enclose the contents of the spermatic cord:

The internal spermatic fascia, which is the deepest layer, arises from the transversalis fascia and is attached to the margins of the deep inguinal ring.

The internal spermatic fascia, which is the deepest layer, arises from the transversalis fascia and is attached to the margins of the deep inguinal ring.

The cremasteric fascia with the associated cremasteric muscle, which is the middle fascial layer, arises from the internal oblique muscle.

The cremasteric fascia with the associated cremasteric muscle, which is the middle fascial layer, arises from the internal oblique muscle.

The external spermatic fascia, which is the most superficial covering of the spermatic cord, arises from the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle and is attached to the margins of the superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 4.47).

The external spermatic fascia, which is the most superficial covering of the spermatic cord, arises from the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle and is attached to the margins of the superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 4.47).

Inguinal hernias

Inguinal hernias are therefore classified as either indirect or direct.

Indirect inguinal hernias

The indirect inguinal hernia is the most common of the two types of inguinal hernia and is much more common in men than in women (Fig. 4.48). It occurs because some part, or all, of the embryonic processus vaginalis remains open or patent. It is therefore referred to as being congenital in origin.

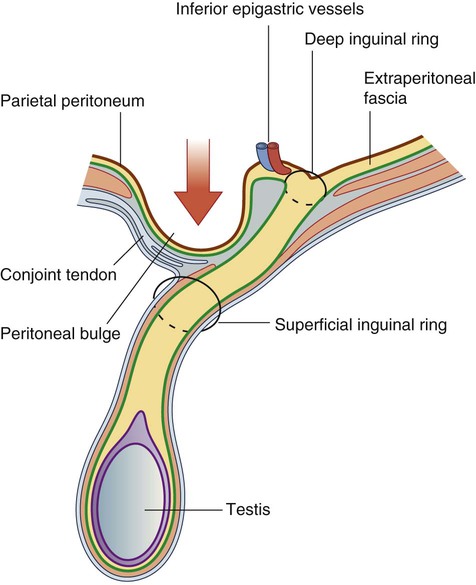

Direct inguinal hernias

A peritoneal sac that enters the medial end of the inguinal canal directly through a weakened posterior wall is a direct inguinal hernia (Fig. 4.49). It is usually described as acquired because it develops when abdominal musculature has been weakened, and is commonly seen in mature men. The bulging occurs medial to the inferior epigastric vessels in the inguinal triangle (Hesselbach’s triangle), which is bounded:

Internally, a thickening of the transversalis fascia (the iliopubic tract) follows the course of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 4.50).