Problem 39 A young man with depressed conscious state and seizures

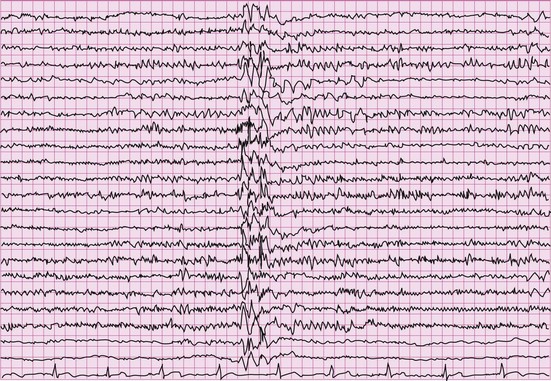

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is performed (Figure 39.1), as one had not been done since diagnosis many years ago. This shows 4–5 Hz paroxysmal generalized polyspike and wave discharges consistent with the diagnosis of primary generalized epilepsy.

Answers

A.1 Hypoglycaemia should be promptly excluded by blood glucose estimation.

Further examination should be undertaken for evidence of:

Only when control of the seizure is obtained can the underlying cause be sought and treated.

A.3 Common causes of status epilepticus in adults include:

* Lorazepam has a much longer half-life than diazepam or midazolam and thus phenytoin is only required if lorazepam fails to stop the seizure. Due to the higher risk of recurrent seizure activity with shorter-acting benzodiazepines, phenytoin should be given prophylatically. One of the leading causes of refractory status epilepticus is early under-management.

Revision Points

Management of the First Seizure

History

From the patient retrospectively, plus an eyewitness account is invaluable:

, http://www.epilepsysociety.org.uk/Forprofessionals. A superb resource for professionals interested in epilepsy from the National Society for Epilepsy. Hundreds of articles, references, literature reviews

, www.epilepsy.org.uk. A good website from the British Epilepsy Association with lots of information for patients, carers, professionals. Lots of links