Problem 14 A woman with acute upper abdominal pain

To refine your list of differential diagnoses you order some investigations.

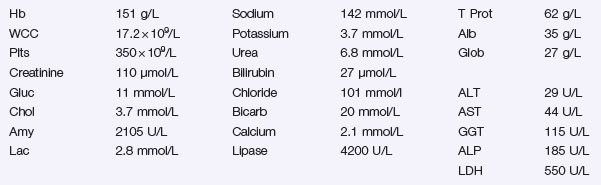

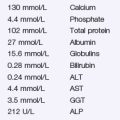

The patient’s ECG reveals a sinus tachycardia and no other changes. Her chest X-ray is shown in Figure 14.1 and her blood test results are shown in Investigation 14.1. Her BMI is calculated to be 34 kg/m2.

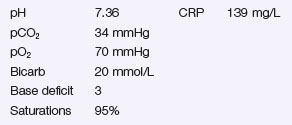

The results of the arterial blood gas analysis on inspired room air and the C-reactive protein (CRP) are shown in Investigation 14.2.

Overnight, she remains stable and begins to feel better.

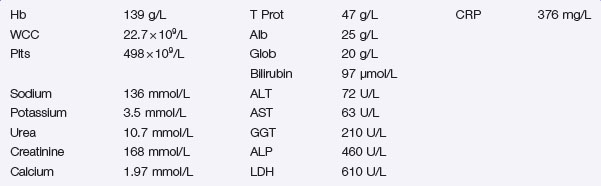

Over the next 24 hours the patient deteriorates. She develops a pyrexia of 38.8°C and becomes jaundiced. She is transferred to the high dependency unit and her repeat blood results are shown in Investigation 14.3.

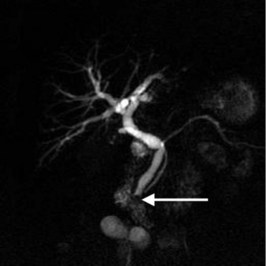

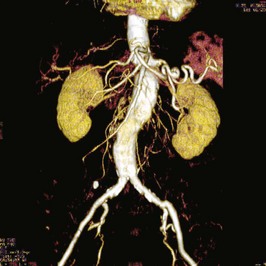

The magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram is shown in Figure 14.2. The MRCP shows dilated intra- and extrahepatic ducts and a solitary stone (arrow) impacted at the bottom of the common bile duct. The pancreatic duct is also visible passing to the right of the picture.

Q.7

Given the clinical deterioration and the radiological findings, what is the next management step?

Answers

She needs arterial blood gas analysis and a C-reactive protein measurement.

Revision Points

Management

Issues to Consider

Ayub K., Slavin J., Imada R. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. 2004, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD003630. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003630.pub2. Provides the evidence base for endoscopic intervention in patients with severe acute pancreatitis due to gallstones

Banks P.A., Freeman M.L. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101:2379-2400. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x The most recent American guidelines published. Advocate abandonment of the Ranson scoring system due to unacceptably poor predictive power

Bollen T.L., van Santvoort H.C., Besselink M.G., et al. The Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis revisited. British Journal of Surgery. 2008;95:6-21.

Mofidi R., Patil P.V., Suttie S.A., et al. Risk assessment in acute pancreatitis. British Journal of Surgery. 2009;96:137-150.

UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut, 54. 2005:1-9. DOI:10.1136/gut.2004.057026 Provide a comprehensive management strategy for patients with acute pancreatitis. Represent the most recent European guidelines published. Updates available at http://gut.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/54/suppl_3/iii1.