7 A systematic approach to herbal prescribing

Chapter contents

Introduction

In order to appreciate a key element of the approach behind Western herbal therapeutics, we must assume that a normally functioning human body is free from disease and capable of resisting disease. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the cause and treatment of disease should also come from a consideration of physiology, the normal functioning of the body, as well as pathology and pathophysiology. An excessive focus on pathology will lead to a medical system which is interventionist and directed towards compensating for the physiological deficiencies and imbalances that arise in disease (physiological compensation), without seeking a greater understanding of how they arose in the first place. Such a basic strategy will lead to a superficial and short-term approach to treatment. This is increasingly the orthodox medical system we have today. While it is very useful for advanced pathologies and life-threatening states, it is incomplete, and especially inadequate in the treatment of many chronic diseases.

Western herbal medicine is also not opposed to employing physiological compensation when needed, although the approach is far less interventionist than that possible with modern drugs. It recognises that a disease process can often create a vicious cycle and that only direct intervention to break that cycle can restore health in some instances. At a pragmatic level, interventionist treatment gives quicker relief of symptoms, which encourages the patient to persist with the treatment. Sometimes, the very concepts treated might require an interventionist approach because they are orthodox concepts, for example, hypertension and high serum cholesterol. This is not to say that a more traditional herbal approach cannot be of assistance as well.

Therapeutic strategy

Physiological enhancement

General strategy

The general treatment goals of physiological enhancement can be elaborated as follows:

• Optimise body chemistry by improving nutrition and enhancing detoxification. This applies not just to the body as a whole but to every cell, organ and system within the body.

• Optimise body energy by raising vitality. Improved vitality automatically follows from optimised body chemistry. But it can also be specifically encouraged using tonics, which make more energy available, and adaptogens, which optimise the capacity to cope with stressors of all kinds, thereby helping to conserve vitality.

Physiological compensation

Sometimes an overstimulated function needs to be directly controlled, or deficiencies need to be compensated, because the pathological process has gone too far. In other cases, a vicious cycle needs to be broken or the patient needs relief from uncomfortable or debilitating symptoms. These are circumstances where physiological compensation is appropriate. Actions which begin with ‘anti’ usually denote a role in physiological compensation, for example, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antispasmodic, antiseptic, antiallergic and so on. Sedative and hypnotic actions also involve compensatory mechanisms and there are many other examples. Many of the ‘specific’ herbs come into this category. Experience has shown that these herbs work well for particular disease states, for example, Tanacetum parthenium and migraine, Arnica and bruises, etc. Their mechanism of action is not necessarily known, but probably involves compensatory effects, although mechanisms that are more fundamental might also apply. Knowledge about ‘specifics’ often originates from folk medicine, where frequently just one herb is used at a time.

Treating the perceived causes

The treatment approach is set out in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Example of a herbal treatment approach for a causal chain

| Link in chain | Treatment | Physiological enhancement (E) or compensation (C) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adaptogens | E |

| 2 | Sedatives | C |

| Hypnotics | C | |

| 3 | Tonics (choosing those which will not aggravate insomnia) | E |

| 4 | Immunostimulants | E |

| 5 | Antivirals | C |

| 6 | Anticatarrhals | C |

| 7 | Expectorants | E |

| Antitussives | C |

Some causes are not treatable by herbal medicine; for example, if insomnia is caused by a traumatic experience, then herbs can compensate but cannot treat or remove the cause. Causes amenable to herbal treatment are listed in Box 7.1.

Some of the causes which cannot be removed but can be compensated for by herbal treatment are listed in Box 7.2.

Often, as part of arriving at an individual treatment framework based on the above considerations, it is necessary to take into account the current medical understanding of the patient’s condition. This understanding needs to be carefully interpreted, but nonetheless the current scientific literature is yielding very useful information. For example, potential causative factors identified in autoimmune disease include chronic bacterial and/or viral infections, abnormal bowel flora, dietary allergies and chemical sensitivities. Factors identified in gastric ulceration include bacterial infection, defective sphincter function and poor mucosal resistance.

The critical role of case taking

• the historical factors behind the development of the presenting complaint

• factors which modify the presenting complaint

• current and previous medication

• information about the patient’s constitution and current condition

• past serious disorders or health problems and disorders related to the presenting complaint, as these can lead to information about underlying causes.

The treatment framework

• The traditional herbal understanding of the disorder

• The clinical experiences of the practitioner in the treatment of the disorder

• A general understanding of the type of the disorder; for example, if it is an infection, what usually leads to this, or if it is an autoimmune disease, the factors that usually precipitate and sustain an autoimmune process

• A scientific understanding of the causes involved in the particular disorder. This information might be derived from clinical and epidemiological studies which have revealed factors which precipitate and sustain the disease process

• A knowledge of scientific studies which have defined the underlying pathological process for that particular disorder

• The individual case history. In a sense, the individual case history acts as a filter for all the above information. An obvious example is lung cancer. Smoking is known to cause lung cancer, but if a patient has never smoked then this consideration is irrelevant to that particular patient. In other words, only those known or suspected causative factors which apply to the particular patient should be incorporated into his or her treatment framework

• The need for symptomatic treatment; again, this relies largely on the individual case history.

For many disorders, development of the treatment framework is a relatively simple process. However, in some instances this process may become quite complex, especially in the case of chronic disorders.

The actions

1. Decide the treatment goals based on traditional herbal concepts, the current medical understanding of the disorder and the patient’s case.

2. Ensure that the goals are individualised to the requirements of the individual case.

3. Decide upon the immediate priorities of treatment.

4. On the basis of the immediate treatment goals, decide what actions are required.

5. Choose reliable herbs which have these actions, with as much overlap as possible. For example, if anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic actions are required for the gut, Matricaria can effectively cover both these requirements. Make sure that these herbs are matched to the patient’s constitution and general condition according to the considerations outlined in Chapter 3.

6. If a particular action needs to be reinforced, do this by choosing more than one herb with this action or by using a very effective herb in a higher dose.

7. Combine the herbs in a formula with appropriate doses (this is usually done as a mixture of fluid extracts or tinctures). Do not choose too many herbs as this will compromise their individual doses in the formula and may lead to undefined interactions.

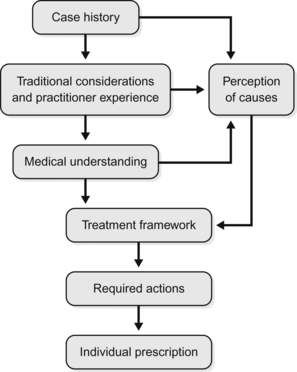

The event sequence in Western herbal therapeutics is summarised in Figure 7.1.

Table 7.2 provides an example of what might form the key treatment goals, relevant herbal actions and resultant candidate herbs for this patient. Referring to the table it can be seen that a number of herbs appear several times, in particular chaste tree and St John’s wort. These are probably the key herbs. Other herbs can be chosen according to their perceived reliability (and associated evidence), the corresponding treatment priorities and the number of times they appear in the table. For this particular case, they would also need to be selected according to their suitability in early pregnancy, should the patient successfully conceive. According to these criteria, such herbs might include passionflower, cramp bark, wild yam and false unicorn root. As Tribulus has clinical trial data for promoting fertility, it could be given priority. A case could be argued for a role for adrenal tonic, adaptogen and general tonic herbs for this patient, in which case they could also be included in the table, with stress management as the treatment goal. Patient energetics and relevant herb-drug interactions can also be taken into account to refine further the prescription.

Table 7.2 Goals, actions and herbs for the case example under discussion (see text)

| Treatment goals | Relevant herbal actions | Candidate herbs |

|---|---|---|

| Improve sleep (sleep maintenance insomnia) | Melatonin boosting | Chaste tree |

| Antidepressant | St John’s wort | |

| Hypnotic | Valerian, passionflower, hops | |

| Alleviate PMS symptoms | Nervine tonic | Skullcap, St John’s wort, Schisandra |

| Female hormonal balancer | Chaste tree | |

| Reduce prolactin levels | Prolactin inhibitor | Chaste tree |

| Normalise cycle | Female hormonal balancer | Chaste tree |

| Stabilise mood and relieve anxiety | Antidepressant | St John’s wort |

| Anxiolytic | Valerian, passionflower, kava | |

| Promote fertility and ovarian function | Progesterogenic (indirect) | Chaste tree |

| Female tonic | Shatavari, dong quai | |

| Ovarian tonic | False unicorn root, Tribulus | |

| Oestrogen modulating | False unicorn root, Tribulus, Paeonia, wild yam | |

| Reduce risk of miscarriage (see also actions for promoting fertility and ovarian function above) | Uterine spasmolytic | Black haw, cramp bark, wild yam |