Chapter 16 A system for the infectious diseases examination

Pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO)

This condition is defined as documented fever (>38 °C) of more than 3 weeks’ duration, where no cause is found despite basic investigations.1,2 The most frequent causes to consider are tuberculosis, occult abscess (usually intra-abdominal), osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis, lymphoma or leukaemia, systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis and drug fever (drug fever is responsible for 10% of fevers leading to hospital admission3). In studies of fever of unknown origin, infection is found to be the cause in 30%, neoplasia in 30%, connective tissue disease in 15% and miscellaneous causes in 15%; in 10% the aetiology remains unknown (Table 16.1). Remember, the longer the duration of the fever, the less likely there is an infectious aetiology. The majority of patients do not have a rare disease but rather a relatively common disease presenting in an unusual way.4

| 1 Neoplasms |

History

The history may give a number of clues in these puzzling cases. In some patients a careful history may give the diagnosis where expensive tests have failed. See Questions box 16.1.

Questions box 16.1

The time course of the fever and any associated symptoms must be uncovered. Symptoms from the various body systems should be sought methodically.

Fever due to bacteraemia (the presence of organisms in the bloodstream) is associated with a higher risk of mortality. It is present in up to 20% of hospital patients with fever.5 Certain clinical findings modestly increase the likelihood of the presence of bacteraemia (Good signs guide 16.1).

| Risk factors | Likelihood ratio if | |

| Present | Absent | |

| Age > 50 | 1.4 | 0.3 |

| Temperature >38.5 | 1.2 | NS |

| Rigors | 1.8 | NS |

| Tachycardia | 1.2 | NS |

| Respiratory rate >20 | NS | NS |

| Hypotension | 2.0 | NS |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4.6 | 0.8 |

| Hospitalisation for trauma | 3.0 | NS |

| Terminal disease | 2.7 | NS |

| Indwelling urinary catheter | 2.4 | NS |

| Central venous catheter | 2.0 | NS |

| ‘Toxic appearance’ | NS | NS |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Examination

General

Look at the temperature chart to see whether there is a pattern of fever that is identifiable. Inspect the patient and decide how seriously ill he or she appears. Look for evidence of weight loss (indicating a chronic illness). Note any skin rash (Table 16.2). The details of the examination required will depend on the patient’s history.

TABLE 16.2 Differential diagnosis of prolonged fever and rash

| 1 Viral: e.g. infectious mononucleosis, rubella, dengue fever |

| 2 Bacterial: e.g. syphilis, Lyme disease |

| 3 Non-infective: e.g. drugs, systemic lupus erythematosus, erythema multiforme (which may also be related to an underlying infection) |

Arms

Inspect for drug injection sites suggesting intravenous drug abuse (see Figure 4.41). Feel for the epitrochlear and axillary nodes (e.g. lymphoma, other malignancy, sarcoidosis, focal infections).

Head and neck

Examine the eyes for iritis or conjunctivitis (connective tissue disease—e.g. Reiter’s syndrome) or jaundice (e.g. ascending cholangitis, blackwater fever in malaria). Look in the fundi for choroidal tubercles in miliary tuberculosis, Roth’s spots in infective endocarditis, and retinal haemorrhages or the infiltrates of leukaemia or lymphoma.

Inspect the face for a butterfly rash (systemic lupus erythematosus, see Figure 9.61, page 284) or seborrhoeic dermatitis, which is common in patients with HIV infection.

HIV infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

This syndrome, first described in 1981, is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).6,7 This is a T-cell lymphotrophic virus, which results in T4 cell destruction and therefore susceptibility to opportunistic infections and the development of tumours, notably Kaposi’s sarcomaa and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Examination

General inspection

Hands and arms

Look for nail changes including onycholysis. Feel for the epitrochlear nodes; a node 0.5 cm or larger may be characteristic.8 Note any injection marks.

Face

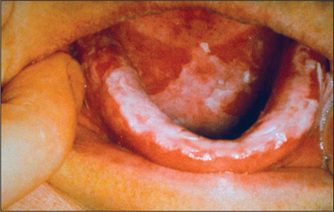

Periodontal disease is very common. Kaposi’s sarcoma (Figures 16.3 and 16.4) may also occur on the hard or soft palate (in which case associated lesions are almost always present elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract). Oral squamous cell carcinoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are more common in AIDS.

Figure 16.3 Kaposi’s sarcoma

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Figure 16.4 Oral candidiasis

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Parotidomegaly is sometimes seen as a result of HIV-associated Sjögren’s syndrome. These patients may have dry eyes and mouth for this reason.

Nervous system

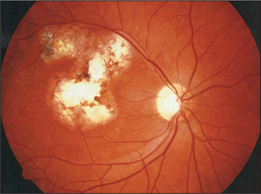

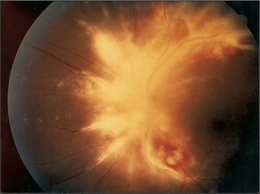

Look in the fundi for cottonwool spots (common in AIDS patients), scars (e.g. toxoplasmosis—Figure 16.5) or retinitis (e.g. cytomegalovirus-induced retinitis with perivascular haemorrhages and fluffy exudates, which can cause blindness of rapid onset—Figure 16.6).10 There may be signs of dementia (AIDS encephalopathy).

1. Knockaert DC, Vanneste LJ, Vanneste SB, Bobbaers HJ. Fever of unknown origin in the 1980s. An update of the diagnostic spectrum. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:51-55.

2. Whitby M. The febrile patient. Aust Fam Phys. 1993;22:1753-1755. 1758–1761

3. Arbo M, et al. Fever of nosocomial origin: etiology, risk factors and outcomes. Am J Med. 1993;95:505-515.

4. Mourad O, Palda V, Detsky AS. A comprehensive evidence based approach to fever of unknown origin. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:545.

5. Bates DW, Cook EF, Goldman L, et al. Predicting bacteremia in hospitalized patients: A prospectively validated model. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:495-500.

6. American College of Physicians and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:310-319.

7. Nandwani R. Human immunodeficiency virus medicine for the MRCP short cases. Br J Hosp Med. 1994;51:353-356.

8. Malin A, Ternouth I, Sarbah S. Epitrochlear nodes as marker of HIV disease in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ. 1994;309:1550-1551.

9. Weinert ML, Grimes RM, Lynch DP. Oral manifestations of HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:485-496. Details the 16 leading oral complications, based on an extensive literature review

10. De Smet MD, Nessenbatt RB. Ocular manifestations of AIDS. JAMA. 1991;266:3019-3022. Provides a very good review of eye changes