Chapter 2 A Multidisciplinary Approach to Cancer

A Surgeon’s View

Introduction

Surgery enables long-term survival and remains the modality central to the opportunity for cure in patients with solid tumors. In order for surgery to be effective, patients must be selected properly so that nontherapeutic surgery is avoided. In the current era of cancer surgery and imaging, “exploratory surgery” should, with the rarest exceptions, not exist as a diagnostic modality. Resectability rates are rising based on improved imaging, but they are admittedly not perfect yet. Whereas involvement of the superior mesenteric artery is predicted with virtually 100% accuracy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, there are some tumor-vessel relationships that cannot be defined with 100% radiologic-clinical correlative accuracy (e.g., hilar cholangiocarcinoma abutment or involvement of a sectoral hepatic artery) and small volume peritoneal disease may not be detected on even the best preoperative imaging.1,2 Furthermore, the interaction between different treatments, including chemotherapy with and without biologically active agents, radiotherapy, intra-arterial therapies, and surgery, require that treatment sequencing, timing, and duration of therapies be considered carefully and contribute to the constant movement in the line defining resectability for many tumors. Before patients embark on complex treatment plans, treatment sequence/timing issues must be considered by a team of physicians—similarly before a patient is declared unresectable (e.g., before applying frequently noncurative therapies such as ablation for hepatic tumors), the multidisciplinary team must often weigh in to assess the spectrum of treatment options. Open communication between surgeons and radiologists change the way surgeons operate and change the way radiologists report their findings to optimize patient care. Patient care is just that—patient care. If the focus of the radiologist, surgeon, radiotherapist, oncologist, and others in the care team is constantly on the patient, the best outcomes can be achieved. If the surgeon operates, the oncologist gives chemotherapy, and the radiation oncologist delivers radiotherapy based on a piece of paper (e.g., a radiology report), the best care cannot be delivered. If the radiologist is integrated into the treatment team, modern, rapidly improving patient outcomes realized in centers of excellence can be achieved more widely. Finally, goals of care differ in different patients. In some, the goal is prevention, in others, diagnosis and treatment. In yet others, the goal may be palliation. Achieving these goals requires actual integration of the members of the treatment team to work together in a patient-focused way.

Candidacy for “potentially curative” therapy is rapidly changing. As an example, many physicians and patients are not aware that multiple, bilateral liver metastases from colorectal or neuroendocrine primary cancers can be treated with curative intent, leading to survival rates exceeding 50% at 5 years post resection.3–5 In such cases, radiology reports of “multiple, bilateral liver metastases” may be accurate, but they may also be misleading to the patient or even to the oncologist/gastroenterologist reading the report (discussed later). Sadly, many clinicians cannot or do not read their films at the time they read the radiology report, and they may misinterpret findings. These factors contribute to the need for precise communication among members of the care team to optimize the value of imaging and optimize patient care. This chapter outlines the following areas:

Diagnosis

In many cases, however, pathologic diagnosis is needed, either to confirm the clinical/radiologic suspicion, as a requirement for treatment by radiotherapy or chemotherapy, or as a requirement for protocol-based therapy. In these cases, the initial imaging will often define whether a percutaneous or an endoscopic approach to biopsy is needed. When percutaneous biopsy is planned, the presumed tumor type and location affect biopsy planning. For liver tumors, biopsy technique significantly affects needle-tract seeding, which should be an extremely rare event (<1%).6,7 Ultrasound-guided lymph node biopsy with core biopsy can provide a diagnosis of lymphoma, although excisional biopsy may be needed and is guided by both clinical examination and cross-sectional imaging. More recently, FDG-PET may demonstrate the most active nodes and guide biopsy planning as well. Seeding is virtually unheard of with the introduction of endoscopic ultrasound–guided biopsy throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, even at the level of obtaining diagnosis, consideration as to the probable diagnosis and possible treatments must often be given, reemphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach when treating cancer patients.

Surgical Planning

Two different examples are described here. First, in the case of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, whether in the head, body, or tail of the pancreas, vascular abutment, encasement, or occlusion by the tumor have been well defined and provoke significantly different treatment approaches (these are discussed in subsequent chapters, and summarized here).8 Further, the vessel involved is important—arterial versus mesenteric/portal venous involvement has significantly different surgical and oncologic implications. In the case of no vascular involvement, straightforward pancreatectomy is generally planned, with pre- or postoperative chemoradiotherapy. In the case of venous involvement, an entirely different operative plan is made to include vascular resection and reconstruction; this picture can change with neoadjuvant therapy. Venous abutment and encasement may not exclude resectability, whereas venous occlusion is considered “borderline” and may be resectable in selected cases. In the case of arterial involvement, preoperative therapy may be advised, and in the case of extensive (>180-degree encasement of the artery), surgery is simply not indicated.8 The finding of liver metastasis excludes the therapeutic value of surgery, even for the smallest resectable primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Regional adenopathy does not exclude resectability. Suggestion of peritoneal disease, which is not definitive, may prompt staging laparoscopy. Thus, accurate staging and reporting of findings relevant to surgery for the specific disease are critical to surgical planning and result from communication between imaging and treating physicians.

As a different example, issues in liver surgery can be even more complex. Resectable liver tumor(s) are often defined based on liver that will remain after resection, including preservation of adequate inflow and outflow to the preserved segments, with adequate liver remnant volumes.9,10 Tumor-vessel relationships within the liver affect resectability differently from that for pancreatic or other gastrointestinal, thoracic, head and neck, or extremity tumors. Tumors may involve two of three outflow vessels (hepatic veins) in the liver and abut the inferior vena cava but be resectable with standard techniques and excellent results.11 Rarely, involvement of all three hepatic veins, traditionally considered a sign of unresectablilty, is not an impediment to complete resection either because vascular resection/reconstruction can be considered or because venous anomalies may permit otherwise impossible resections such as subtotal hepatectomy based on the presence of a dominant inferior right hepatic vein.12,13 Major hepatectomy includes resection of tumors involving major hepatic and portal branches routinely, as long as vessels supplying and draining the liver remnant are free of tumor. In other cases, major resection is possible because of other anatomic variations in the liver, such as a staged portal bifurcation allowing resection of tumors involving the central liver.

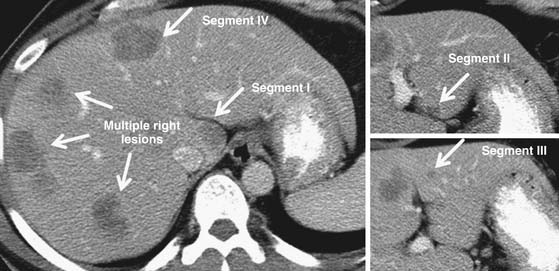

Thus, surgeons and radiologists must understand liver parenchymal and vascular anatomy, such as of the hepatic veins, portal veins, hepatic arteries, and must remark variations including replaced or accessory hepatic arteries (present in up to 55% of patients) or even the existence of important venous variants.14 Even segmental liver volume is highly variable, which affects surgical planning.15 Systematic liver volumetry based on cross-sectional imaging is a critical tool for surgical planning for major liver resection, reiterating the intersection of radiologists and surgeons in surgical planning.9,10 Radiologists and surgeons who work together are aware of the importance of anatomic variations and tumor-vessel relationships, leading to different radiologic reports—reports that guide patients and clinicians who care for them with the help of high-quality imaging and imaging interpretation. An example synthesizing these issues in a patient with multiple bilateral colorectal liver metastases is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Finally, advances in imaging have advanced the correlation between imaging findings and patient outcomes. Two examples warrant comment, both of which relate to the treatment of solid tumors with “biologic” agents and assessment of response on computed tomography (and/or PET). First is gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), treated with imatinib mesylate, an inhibitor of c-kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-a (PDGFRa) tyrosine kinases. Traditional methods of assessing response such as RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) are used to capture the effect of this class of new agents, which cause less size change and more cystic change and loss of vascularity of GIST tumors, leading to a shift in assessment of response in these tumors using different radiologic criteria.16,17 Even in colorectal liver metastases, RECIST is a poor indicator of response to newer agents such as bevacizumab, a vascular endothelial growth factor antagonist. Study has shown that morphologic criteria that focus not on tumor size changes but on changes in vascularity and margin between tumor and liver predict survival in patients with resectable and unresectable colorectal liver metastases treated with bevacizumab and that the morphologic radiologic response (but not RECIST) correlates with pathologic response to chemotherapy, a true survival predictor.18 These examples of advances in imaging, and correlation between newer imaging findings and outcomes, are important to surgeons and physicians who determine treatment plans—at the same time, shortcomings of even the most modern imaging techniques must be considered. The absence of PET activity or arterial enhancement of a GIST or colorectal liver metastasis almost never (<10%) indicates cure, so again, oncologists, surgeons, and radiologists must avoid overinterpretation of findings on imaging before treatment decisions are made.19

Surgical Treatment

Treatment objectives differ depending on tumor types, stages, and locations:

• Definitive resection of primary tumors

• Definitive resection of metastatic tumors

Definitive Resection of Primary Tumors

Treatment with curative or definitive intent is often the goal of surgical therapy, whether surgery is a stand-alone treatment or part of a multipronged approach to cancer with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Treatments of many primary tumors affect quality of life (e.g., craniofacial tumors, extremity tumors, gastrointestinal/genitourinary tumors) because they cause permanent deformity or other alterations to the patient, such as ostomy. Oncologic surgery typically implies surgery along anatomic planes (perhaps excluding some soft tissue tumors); most solid tumors are resected with regional lymph nodes. Some lymph node basins are of significant interest because metastases in distant basins may indicate advanced disease and contraindicate surgery (e.g., interaortocaval nodal metastasis from gallbladder cancer). Many solid tumors can be resected with curative intent including adjacent structures/organs (T4 colon tumors, some pancreatic neoplasms). Some primary tumors are appropriately resected despite the presence or even unresectability of metastatic tumors (e.g., small bowel neuroendocrine tumors without peritoneal metastases but with unresectable but controllable liver metastases). The appropriate margin of resection may be a specific distance (millimeters of normal liver for a liver tumor, millimeters of esophagus or pharynx for an upper gastrointestinal tumor) or simply an anatomic plane (a fat plane along the superior mesenteric artery for a pancreatic adenocarcinoma), and millimeters may be the difference between leaving a patient with a permanent ostomy or continuity of the gastrointestinal tract (as for low rectal cancer). Knowledge of relevant disease- and tumor-specific concepts are realized when surgeons and radiologists work together.

Definitive Resection of Metastatic Tumors

As mentioned previously, many metastatic tumors require surgery. Colorectal, neuroendocrine, other endocrine and noncolorectal, nonendocrine primary cancers that metastasize to the liver and lung can be resected with expectation of long-term survival or even cure.20–22 Barriers to resectability have been shattered in the best studied subgroup, those with liver metastases from colorectal cancer with survivals following resection exceeding 50% at 5 years.9 As mentioned, criteria for resectability of this and other metastatic tumors to the liver considered appropriate for surgical therapy no longer consider number or size of tumors, rather resectability is defined by9

• Potential for definitive treatment of the primary tumor.

• Potential to remove all tumor deposits with adequate margin.

• Potential to leave adequate liver remnant post resection (based on three-dimensional liver volumetry).

• Potential to preserve adequate inflow, outflow, and biliary drainage of the future liver remnant.

Gone are the days of counting tumors or measuring the size of tumors to determine resectability—rather the search is made for an anatomic region of the liver relatively spared by disease that can be preserved as the future liver remnant.23 If that future remnant will be too small to support postresection liver function, modern interventional radiologic techniques permit percutaneous embolization of the portal branches supplying the liver to be resected, leading to diversion of portal flow to the future liver remnant, and a shift in liver function from tumors in the liver to be resected toward the disease-free liver that will remain.23,24 Extended hepatic resection is safe, and even two-stage liver resection (clearance of the future remnant in a first operation involving minor resections preserving the bulk of parenchyma on one side of the liver), followed by portal vein embolization (if needed to divert portal flow to the now disease-free liver remnant inducing hypertrophy), followed by major hepatectomy (hemihepatectomy or extended hepatectomy) leaves patients with preserved liver function and normal performance status and allows long-term survival3,11 (see Figure 2-1). Safety of extended liver resection, whether for primary liver tumors, biliary tumors, or secondary (metastatic) tumors, relies uniformly on liver remnant volume, which is interpreted on the basis of liver disease. Imaging evidence of liver disease such as cirrhosis, portal hypertension, varices, fatty liver, and treatment-related changes in the liver over time is evaluated by surgeons considering major liver surgery.

Curative metastasectomy is often combined with chemotherapy before and/or after resection. Other methods of tumor destruction can be considered for primary liver tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients or as an adjunct to contralateral major resection, but with results significantly inferior to resection, depending on the clinical situation. Ablation technologies are extensively overused, likely because of the lack of access to hepatic surgeons with experience who might perform appropriate resections for such patients—further highlighting the need for multidisciplinary consideration before noncurative treatments are applied to patients who are otherwise candidates for cure.20 In some cases, ablative techniques are the best choice (e.g., hepatocellular carcinoma in severe cirrhosis) because other options (transplantation or resection) are contraindicated; in others, ablation may help to control disease or systemic manifestation of disease (such as carcinoid, which produces a systemic hormonal syndrome). Often, however, ablation is performed when resection using advanced techniques would have been a better choice, emphasizing the need for timely, multidisciplinary discussion before treatment plans are made that may not be in the patient’s best interest.

Debulking Surgery

Debulking is rarely indicated for solid tumors except in a few rare cases. In virtually all tumor types amenable to debulking, chemotherapy is also used. The best studied cancers in which debulking significantly benefits patients are peritoneal surface malignancies, such as mucinous appendiceal cancers and ovarian cancers.25 Selected patients undergo peritonectomy and debulking, often with resection of bowel, stomach, spleen, colorectum—followed in some cases by hyperthermic peritoneal chemotherapy.25 Rarely, metastatic liver tumors such as small bowel carcinoid or functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors may require debulking when they create intolerable hormonal syndrome by partial hepatectomy with or without in situ ablation, although not all centers agree with this approach and prefer to resect/ablate when all disease can be completely addressed, even if only with a close margin.5,26

Palliative and Emergency Surgery

Palliative surgery is an art and is less and less commonly performed even at major cancer centers. Bypass of gastric outlet obstruction, the biliary tract, and the rectum has largely been supplanted by percutaneous and endoscopic measures to intubate and dilate symptomatic strictures or place draining tubes such as percutaneous gastrectomy or percutaneous transhepatic catheters, avoiding the need for surgery in patients with unresectable disease. Many strictures can be palliated with metallic totally internal stents inserted by endoscopic or percutaneous routes. Further, more effective chemotherapy and radiotherapy may resolve or control some malignant problems to be avoided or ameliorated, such as malignant obstruction and bleeding. Consideration for bypass surgery or ostomy is made after careful clinical consideration and complementary radiographic assessment to ensure that surgery to bypass a stricture will achieve the goal of improving the patient’s condition—for example, a gastroenterostomy performed for “gastric outlet obstruction,” which is not physical obstruction but related to a tumor invading the celiac plexus creating a functional obstruction that will not significantly improve the patient’s ability to eat.

Emergency surgery in cancer patients is even more rarely needed. Ruptured/bleeding hepatic tumors should almost always be embolized, and surgery considered only when the patient is stable.27 Surgery for malignant obstruction in a patient with carcinomatosis may or may not be appropriate because it may potentiate the patient’s decline rather than palliate the obstructive symptoms (carcinomatosis in some cases makes it impossible to safely enter the abdomen or create an internal bypass; rather, surgery leads to fistulas, open wounds, and other problems that in no way achieve the goal of treatment). Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract may indicate urgent surgery in patients who have treatment options (e.g., obstructing rectal tumors), but even in these cases, the operation conducted (tumor resection with ostomy vs. diverting ostomy only) must be considered based on the clinical scenario and imaging.

Summary

• Surgery remains the pillar of treatment for “cure” of solid tumors but does not stand alone in this endeavor, which requires a skilled multidisciplinary team that communicates effectively to optimize patient care.

• Patient selection is critical to ensure optimal surgical outcomes, which depend in turn on high-quality preoperative imaging and accurate reading and reporting of findings.

• Diagnosis, staging, and careful reporting of relevant anatomic findings are critical elements surgeons seek in preoperative imaging studies and reports.

• “Exploratory” surgery should be a thing of the past—surgery should be conducted with specific objectives, for definitive resection of primary or metastatic tumors, debulking for certain tumor types, palliation when nonsurgical alternatives do not exist, rarely in emergency situations, and for reconstruction at the time of resection or at a separate stage to restore function or cosmesis after cancer surgery.

1. Fuhrman G.M., Charnsangavej C., Abbruzzese J.L., et al. Thin-section contrast-enhanced computed tomography accurately predicts the resectability of malignant pancreatic neoplasms. Am J Surg. 1994;167:104-111. discussion 111–113

2. Aloia T.A., Charnsangavej C., Faria S., et al. High-resolution computed tomography accurately predicts resectability in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2007;193:702-706.

3. Chun Y.S., Vauthey J.N., Ribero D., et al. Systemic chemotherapy and two-stage hepatectomy for extensive bilateral colorectal liver metastases: perioperative safety and survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1498-1504.

4. Frilling A., Sotiropoulos G.C., Li J., et al. Multimodal management of neuroendocrine liver metastases. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:361-379.

5. Glazer E.S., Tseng J.F., Al-Refaie W., et al. Long-term survival after surgical management of neuroendocrine hepatic metastases. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:427-433.

6. Abdalla E.K., Vauthey J.N. Technique and patient selection, not the needle, determine outcome of percutaneous intervention for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:240-241.

7. Azoulay D., Johann M., Raccuia J.S., et al. “Protected” double needle biopsy technique for hepatic tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:160-163.

8. Katz M.H., Pisters P.W., Evans D.B., et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:833-846. discussion 846–848

9. Abdalla E.K., Adam R., Bilchik A.J., et al. Improving resectability of hepatic colorectal metastases: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1271-1280.

10. Vauthey J.N., Dixon E., Abdalla E.K., et al. Pretreatment assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:289-299.

11. Kishi Y., Abdalla E.K., Chun Y.S., et al. Three hundred and one consecutive extended right hepatectomies: evaluation of outcome based on systematic liver volumetry. Ann Surg. 2009;250:540-548.

12. Hemming A.W., Reed A.I., Langham M.R., et al. Hepatic vein reconstruction for resection of hepatic tumors. Ann Surg. 2002;235:850-858.

13. Zorzi D., Abdalla E.K., Pawlik T.M., et al. Subtotal hepatectomy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for a previously unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:347-350.

14. Michels N.A. Newer anatomy of the liver and its variant blood supply and collateral circulation. Am J Surg. 1966;112:337-347.

15. Abdalla E.K., Denys A., Chevalier P., et al. Total and segmental liver volume variations: implications for liver surgery. Surgery. 2004;135:404-410.

16. Therasse P., Arbuck S.G., Eisenhauer E.A., et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205-216.

17. Choi H., Charnsangavej C., de Castro Faria S., et al. CT evaluation of the response of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after imatinib mesylate treatment: a quantitative analysis correlated with FDG PET findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1619-1628.

18. Chun Y.S., Vauthey J.N., Boonsirikamchai P., et al. Association of computed tomography morphologic criteria with pathologic response and survival in patients treated with bevacizumab for colorectal liver metastases. JAMA. 2009;302:2338-2344.

19. Blazer D.G.3rd, Kishi Y., Maru D.M., et al. Pathologic response to preoperative chemotherapy: a new outcome end point after resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5344-5351.

20. Abdalla E.K., Vauthey J.N., Ellis L.M., et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818-825.

21. Adam R., Chiche L., Aloia T., et al. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases: analysis of 1,452 patients and development of a prognostic model. Ann Surg. 2006;244:524-535.

22. Tomlinson J.S., Jarnagin W.R., DeMatteo R.P., et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4575-4580.

23. Abdalla E.K., Hicks M.E., Vauthey J.N. Portal vein embolization: rationale, technique and future prospects. Br J Surg. 2001;88:165-175.

24. Madoff D.C., Abdalla E.K., Vauthey J.N. Portal vein embolization in preparation for major hepatic resection: evolution of a new standard of care. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:779-790.

25. Glockzin G., Schlitt H.J., Piso P. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: patients selection, perioperative complications and quality of life related to cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:5.

26. Sarmiento J.M., Heywood G., Rubin J., et al. Surgical treatment of neuroendocrine metastases to the liver: a plea for resection to increase survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:29-37.

27. Liu C.L., Fan S.T., Lo C.M., et al. Management of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: single-center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3725-3732.