Chapter 1 A Multidisciplinary Approach to Cancer

A Radiologist’s View

Introduction

Imaging plays a central role in the care of patients with cancer. Subsequent chapters deal with some of the specifics regarding the use of imaging in the multidisciplinary environment, such as tumor staging, lesion respectability, and treatment-related complications. Many clinical decisions are influenced by the results of imaging studies, and the radiologist must, therefore, be a central member of the multidisciplinary care team. The significant role of imaging can be seen in the continued growth in the numbers of scans performed each year, particularly in the advanced imaging studies such as x-ray computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron-emission tomography with x-ray CT (PET/CT).1

Multidisciplinary Cancer Imaging: The Role of the Radiologist

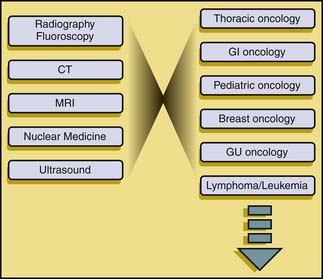

This increase in the breadth and complexity of radiology and nuclear medicine has necessitated a shift in practice patterns at many sites. In order to effectively function in the multidisciplinary environment of an academic cancer hospital, radiologists have needed to specialize. Radiology specialization has traditionally been either by modality (e.g., ultrasound, CT) or by system (e.g., body imaging, neuroradiology, thoracic radiology). The clinical specialties, conversely, have trended toward specialization according to disease. At M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, there are multidisciplinary care teams devoted to the care of patients with various malignancies. Each care team is composed of multiple members from various disciplines, including surgery, medical oncology, and radiation therapy. In order to adapt to the multidisciplinary paradigm, imaging has had to adapt from the traditional modality-based and system-based approaches to a disease-oriented framework (Figure 1-1).

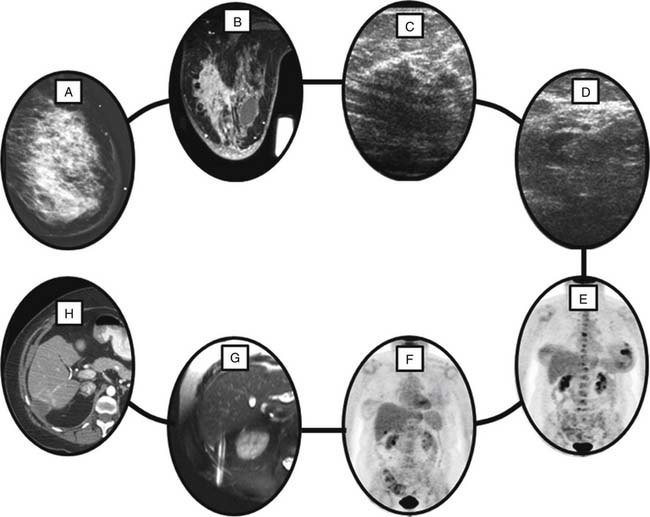

The challenge for the radiologist is that the diagnostic imaging within each of the multidisciplinary centers crosses the boundaries between traditional imaging specialties. To take an example, a woman with newly diagnosed, locally advanced breast cancer presents for workup (Figure 1-2). Breast imaging plays a central role in her evaluation, starting with mammography and moving to breast ultrasound and/or MRI as needed. Her pathologic diagnosis and tumor genetic markers will likely be established by a guided biopsy procedure. Further imaging workup of such a patient may include a contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and abdomen or a radionuclide bone scan for detection of osseous metastatic disease. The workup may stop there, but depending on many clinical factors such as signs and symptoms and serum tumor markers, additional imaging may be requested including PET/CT with fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), or brain MRI.

Cancer imaging in a multidisciplinary environment provides the opportunity to become directly involved in the decision-making processes of patient care and to learn about the role and relevance of imaging within the broad clinical picture. There are challenges in adapting from the traditional modality-based or region-based practice of imaging to a disease-based approach, but these challenges can be met with adaptation and communication.

The Value of Communication

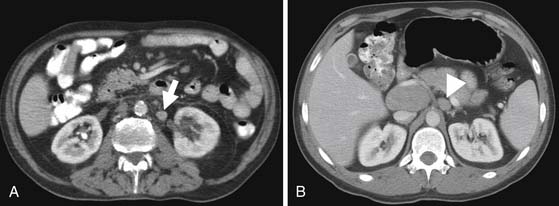

In the setting of multidisciplinary cancer care, the challenge for the radiologist is to fully understand the clinical questions for different disease types. The information relevant to the care of patients with different types of malignancies can be quite diverse. As an example (Figure 1-3), patient A has newly diagnosed esophageal cancer, verified by endoscopic biopsy. Patient B has newly diagnosed large B-cell lymphoma, diagnosed by a retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy of a known retroperitoneal mass. Both patients undergo FDG-PET/CT, and each is found to have a hypermetabolic nodal mass in the left para-aortic space of the retroperitoneum below the celiac trunk. In patient B, in which this additional node is almost certainly a manifestation of retroperitoneal lymphoma, it has little additional significance because it does not change the stage of the patient’s disease. In patient A, this node is, however, a critical finding, changing management from chemoradiation and potentially curative surgery to palliative chemotherapy or chemoradiation. An identical finding in these two patients has markedly different significance in terms of the fundamental clinical question of tumor stage and appropriate therapy and the reporting should reflect this.

Answering the clinical question, therefore, becomes a matter of, first, understanding the disease process enough to appreciate the relative importance of various radiologic findings and, then, of reporting those findings in an effective manner. A helpful framework for high-quality radiology reporting is the eight Cs of effective reporting (Table 1-1). This framework was initially put forward by Armas2 as six Cs, and expanded to eight Cs by Reiner and colleagues.3 The eight Cs are Correctness, Completeness, Consistency, Communication, Clarity, Confidence, Concision, and Consultation. These are useful measures of effective reporting, particularly in the setting of a multidisciplinary cancer care system.

| Correctness | Clarity |

| Completeness | Confidence |

| Consistency | Concision |

| Communication | Consultation |

From Reiner BI, Knight N, Siegel EL. Radiology reporting, past, present, and future: the radiologist’s perspective. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4:313-319.

Correctness is perhaps the most basic of these concepts, but at the same time, it is not as absolute as it seems. Everyone strives for the correct diagnosis in radiology reporting, yet given the complexities of imaging, it is not always possible to arrive at the correct diagnosis. In fact, there are situations in which the best scan interpretation may not contain the correct diagnosis. For example, a patient with prior non–small cell lung cancer presents with a new slowly enlarging speculated pulmonary nodule. The report of the chest CT appropriately suggests metastatic disease, and a percutaneous biopsy is performed. The biopsy shows inflammatory reaction and fungal elements, and a diagnosis of Nocardia infection is made. In this case, the CT report was not “correct” in the sense of making the appropriate diagnosis; however, the workup generated by the CT report was appropriate, and the diagnosis of fungal infection was made allowing for treatment with antibiotics. The emphasis might, therefore, better be placed on interpreting studies in the correct fashion (i.e., up to the standards of good medical practice) rather than focusing on the correct diagnosis.4

Completeness and consistency are related parameters. Completeness is defined as containing all the parts and elements necessary for a high-quality report, and consistency implies structure to the report, applied over time. Both of these elements can be achieved through the use of reporting templates or standardized reporting. A representative guideline for reporting of PET/CT scans is provided by the Society of Nuclear Medicine’s PET Center of Excellence, outlining the components of an effective PET/CT report in oncology.5 Other guidelines and templates exist for other imaging modalities.

Communication is the core of quality in the field of imaging. The best images obtained on the newest scanner and interpreted by the best-trained radiologist can be clinically useless if the results are not effectively communicated to the referring clinician. Often, the written report is the only interface between the radiologist and the clinician. Special care must, therefore, be given to the structuring of the report to ensure the message is delivered in an appropriate fashion. The final four Cs can be seen as tools to achieve that effective communication.

Clarity means that the opinion of the radiologist is clearly stated in the report. In the arena of oncologic imaging, this may mean definitively categorizing into one of the four criteria outlined in the World Health Organization (WHO) and RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) criteria6–8: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD). Clarity does not necessarily imply a single diagnosis because many radiologic findings require an organized and logically ordered differential diagnosis. Further clarity can be achieved with the addition of next-steps, if appropriate.

1. IMV 2006 CT Market Summary Report. Des Plaines, IL: IMV Medical Information Division; 2006.

2. Armas R.R. Qualities of a good radiology report. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1110.

3. Reiner B.I., Knight N., Siegel E.L. Radiology reporting, past, present, and future: the radiologist’s perspective. J Am Coll Radiol. 2007;4:313-319.

4. Gunderman R.B., Nyce J.M. The tyranny of accuracy in radiologic education. Radiology. 2002;222:297-300.

5. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/docs/PET_PROS/ElementsofPETCTReporting.pdf

6. Miller A.B., Hoogstraten B., Staquet M., Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:208-214.

7. Therasse P., Arbuck S.G., Eisenhauer E.A., et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205-216.

8. Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247.