Chapter 42 A minimally invasive technique for tongue base stabilization

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) results from a complex scenario initiated with airway collapse and obstruction, loss of compensatory wake and sleep reflexes, increased ventilatory effort, arousal, hypoventilation, and asphyxia during sleep. In adults, a structurally small upper airway may be a primary contributing factor. Enlarging this airway may prevent the cascade into sleep apnea and snoring.

2 RATIONALE

Obstruction during sleep is the result of a complex cascade. During inspiration, upper (pharynx) and lower (chest wall and diaphragm) airway muscles are activated. The lower airway muscles create a negative intraluminal force balanced by upper airway muscles that stiffen and dilate the airway. Increases in negative airway pressure or loss of muscle dilation will obstruct the airway. In sleep-disordered breathing both occur. Increased upper airway resistance leads to more negative intraluminal pressure and activation of upper airway dilator muscles is delayed or decreased. During expiration, positive pressure forces dilate the airway, and upper airway muscle tone is reduced. If the balance is unfavorable and the effects of tissue mass are not compensated, collapse and obstruction occur.

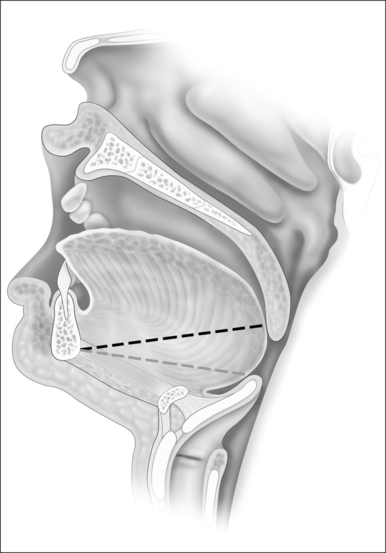

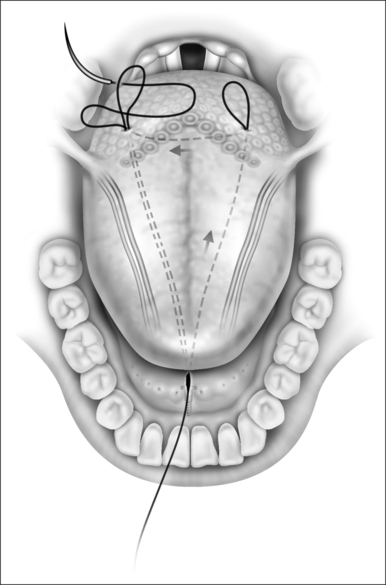

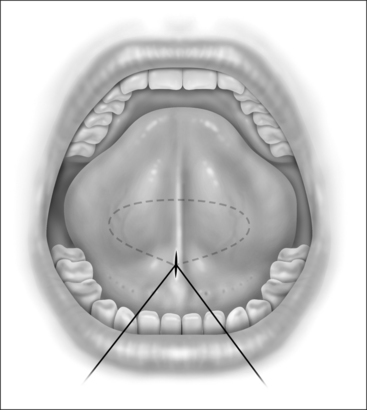

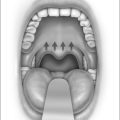

Since during expiration the largest decreases in airway size occur in the hypopharynx, treatment of this segment may be critical for most if not all individuals with sleep-disordered breathing. The tongue suspension procedure was conceived as a means of providing an extraluminal dilating force to the lower pharyngeal airway in contrast to nasal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) which is an intraluminal dilating force. This is accomplished by passing a submucosal suture into the posterior midline tongue. The suture prevents passive collapse while not interfering with anterior and superior tongue movements which are involved with swallowing and speech. Placement is directed towards the level of the foramen cecum (Fig. 42.1).

3 TONGUE SUTURE SUSPENSION TECHNIQUE

3.1 STEP ONE (BONE ANCHOR)

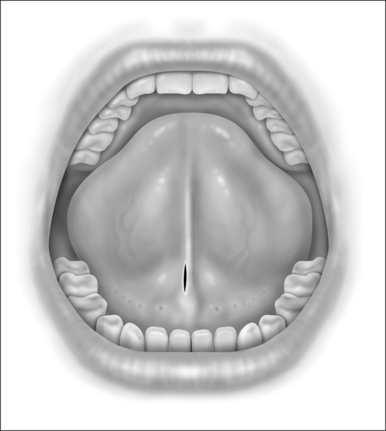

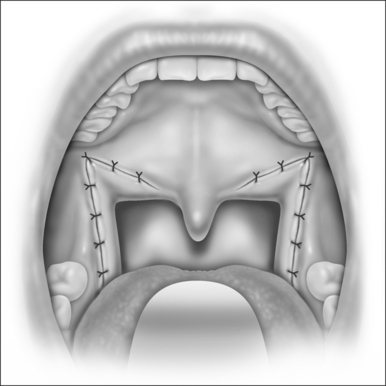

When performing the intraoral approach, an intraoral incision is made posterior to the salivary papillae (Fig. 42.2). The incision should be generous. An excessively long linear incision is easily closed with excellent healing. An incision too small for the device may result in mucosal tearing that may damage the papillae and create an intraoral scar. If an external incision is used an incision is made 1cm posterior to the gnathion in a convenient skin crease or shadow.

3.2 STEP TWO

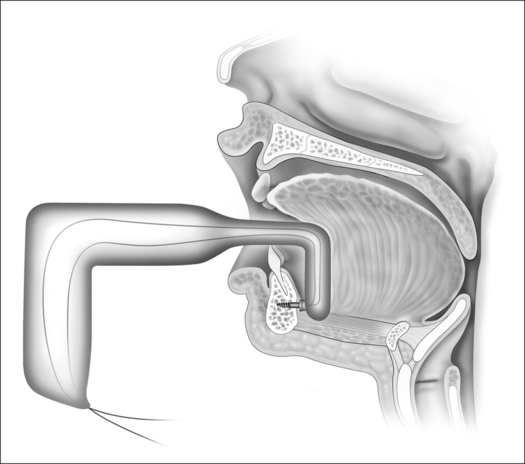

The suture is anchored to the bone. Two methods may be used. One method is an intraoral approach using the Repose (Influ-ENT Ltd, Concord, NH) bone screwanchoring device. Alternatively the suture may be anchored externally using the Repose device or other methods to anchor the suture to the inferior mandible. The Repose bone screw system consists of the U-shaped bone screw inserter that is used to place the bone screw onto the lingual surface of the mandible through an incision in the floor of mouth. It also includes the self-tapping titanium screw which is attached to two 1-0 Prolene sutures (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) at its base. Lastly, a suture passer is included to pass the suture through the tongue base.

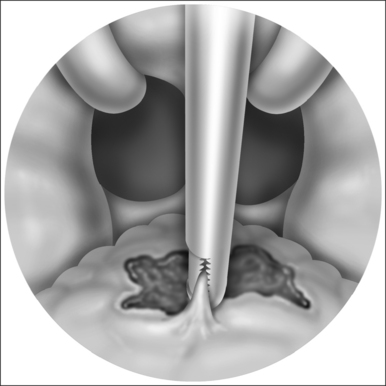

A tunnel is created by dissecting between the genioglossus muscle bellies in the midline with a curved or right angle mixture hemostat. Intraorally, dissection is posterior and deep to Wharton’s ducts and is carried palpably to bone. Soft tissue may be gently scraped from the bone at this juncture. If using the Repose device intraorally, placement of the bone screw inserter into the mouth may be difficult in an OSA patient. The back blunt end of the distal device may first be placed into the mouth. The bone-anchoring screw may then be placed into the intraoral incision and then through the midline tunnel down to bone. Care must be taken to place the bone screw below the tooth roots. Using force and orienting the screw perpendicular to the mandibular cortex, the driver is placed against the mandible and inserted with the battery-operated inserter (Fig. 42.3). Alternatively, a Prolene suture may be directly anchored by drilling two parallel holes in the inferior mandible. The end (s) of the suture may then be looped through this attachment.

3.3 STEP THREE

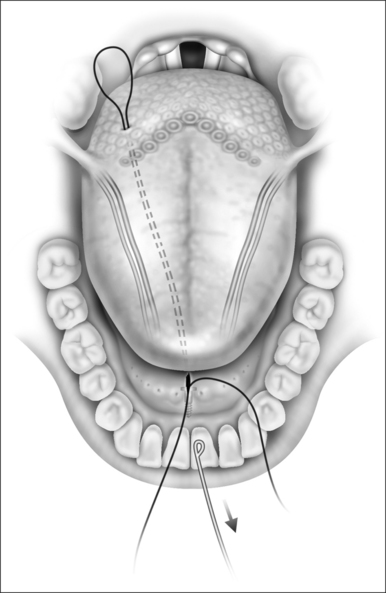

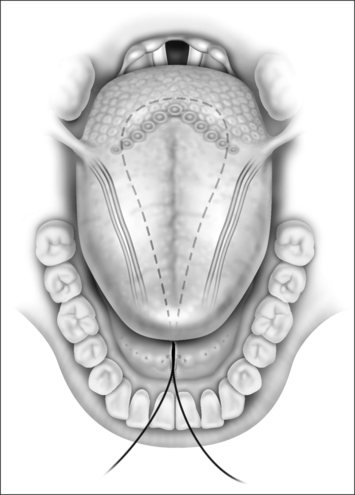

The suture that is attached to the mandible is then advanced to the tongue base about 1–1.5cm lateral to the midline with an awl or a suture passer (Fig. 42.4). An empty suture loop is passed in a similar manner on the opposite side of the tongue taking care to avoid the neurovascular bundle that lies laterally. The suture attached to the screw is then threaded onto an empty Mayo needle, inserted into its own exit site on the tongue base and passed submucosally to the exit site of the second suture so that it is threaded into the loop of the second suture (Fig. 42.5). The second suture (the empty suture loop) is then pulled back to the anterior attachment. The Prolene suture attached to the mandible now is in a triangular configuration (Fig. 42.6). The suture is tied to itself and the knot is buried (Fig. 42.7). It is important that the tension on this suture be enough to feel a dimple on the posterior tongue base, but not so great as to cause strangulation. The correct angulation is undetermined and whether effectiveness is altered based on an intraoral or external approach is not known.

4 PATIENT SELECTION

Selection of the best candidates for this technique is based on anecdotal reports, clinical experience, and a few surgical case series. Contraindications to this procedure include poor general medical health or primary upper airway obstruction in the retropalatal region. In addition, relative contraindications include macroglossia, abnormal mandible bone, poor oral hygiene, and severe periodontal disease,history of radiation or history of root canal proceduresin the mandibular midline incisors. Since this procedure conceptually does not actively advance tissues, patientswith severe obstruction due to excessive tissue volume of the tongue or lateral walls will probably not respond. Patients who have personally responded the best were those without significant macroglossia or lateral wall collapse, and whose posterior airspace dramatically decreased in size going from the sitting to supine position (observed endoscopically).

5 DISCUSSION

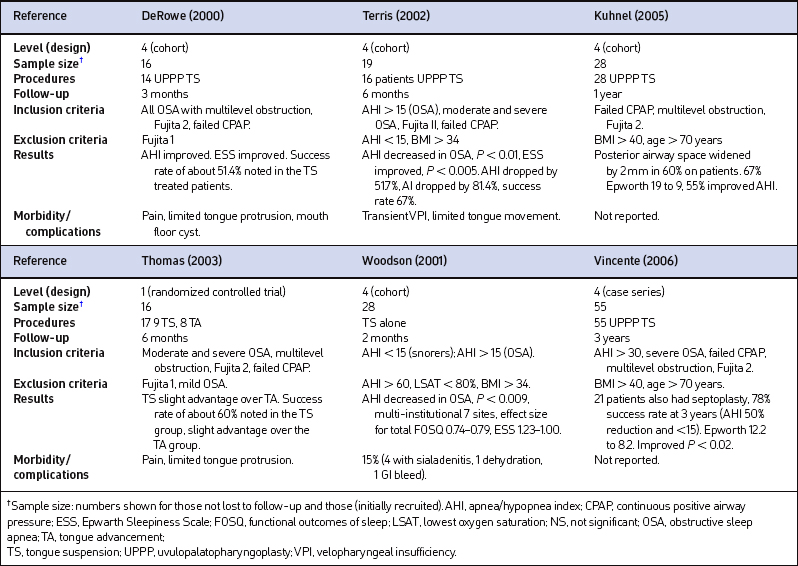

Published studies of tongue suspension to treat sleep apnea are primarily non-randomized, uncontrolled case series with short-duration follow-up. Most combine UPPP as part of the treatment. Extrapolating results is difficult (Table 42.1). In general, snoring and sleep-related outcomes improve. Snoring may still be bothersome. Postoperative morbidity includes moderate to severe pain, difficulty with speech, swallowing and drooling and transient VPI. Duration has been reported from 7 to 28 days. No long-term speech or swallowing problems were reported in the initial studies.

Complications include delayed floor of mouth sialadenitis, dehydration, delayed gastrointestinal bleeding, floor of mouth hematoma, and prolonged pain/infection leading to removal or loosening of the suture. Other complications include damage to the neurovascular bundle (lingual artery and hypoglossal nerve), osteomyelitis and damage to dental structures. To reduce the risk of these problems, perioperative antibiotics and steroids are recommended. A meticulous technique should be used to ensure that the neurovascular bundle and Wharton’s ducts are avoided and the suture buried.

1. DeRowe A, Gunther E, Fibbi A, et al. Tongue-base suspension with a soft tissue-to-bone anchor for obstructive sleep apnea: preliminary clinical results of a new minimally invasive technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:100-103.

2. Woodson BT, DeRowe A, Hawke M, et al. Pharyngeal suspension suture with Repose bone screw for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:395-401.

3. Woodson BT. A tongue suspension suture for obstructive sleep apnea and snorers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:297-303.

4. Terris DJ, Kunda LD, Gonella MC. Minimally invasive tongue base surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(9):716-721.

5. Miller FR, Watson D, Malis D. Role of the tongue base suspension suture with The Repose System bone screw in the multilevel surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;126(4):392-398. AU: Copy-ed has inserted year. Is 2004 correct?

6. Thomas AJ, Chavoya M, Terris DJ. Preliminary finding from a prospective. randomized trial of two tongue-base surgeries for sleep-disordered breathing, Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(5):539-546.

7. Kuhnel TS, Schurr C, Wagner B, et al. Morphological changes of the posterior airway space after tongue base suspension. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(3):475-480.

8. Omur M, Ozturan D, Elez F, Unver C, Derman S. Tongue base suspension combined with UPPP in severe OSA patients. Otol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:218-223.

9. Vicente E, Marin JM, Carrizzo S, Naya MJ. Tongue-base suspension in conjunction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for treatment of severe obstructive sleep apnea: long-term follow-up results. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):L1223-L1227.