Chapter 1 A Life-Course Perspective for Women’s Health Care

SAFE, ETHICAL, AND EFFECTIVE PRACTICE

Principles of Practice Management

Principles of Practice Management

LIFE-COURSE PERSPECTIVE

Where does the rubber meet the road and lead to pathology and disease during the course of life?

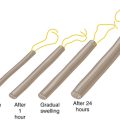

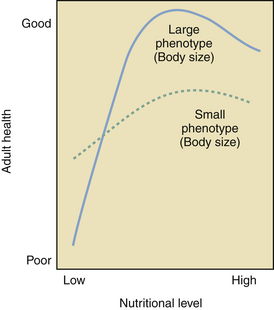

In relation to individual X and individual Y with the same genomic makeup but different in utero environmental influences, metabolic changes that may be initiated in utero in response to inadequate nutritional supplies (Figure 1-1) can lead to insulin resistance and eventually the development of type 2 diabetes. These adaptive changes can even result in a reduced number of nephrons in the kidneys as a stressed fetus conserves limited nutritional resources for more important in utero organ systems. This can then lead to a greater risk for hypertension later in life. This series of initially protective but eventually harmful developmental changes was first described in humans by David Barker, a British epidemiologist, who carefully assessed birth records of individuals and linked low birth weight to the development of hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and stroke later in life. The association among poor fetal growth during intrauterine life, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease is known as the Barker hypothesis. The process whereby a stimulus or insult, at a sensitive or critical period of fetal development, induces permanent alterations in the structure and functions of the baby’s vital organs, with lasting or lifelong consequences for health and disease, is now commonly referred to as developmental programming.

Patient Safety

Patient Safety

Ethical Practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Ethical Practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology

ETHICAL PRINCIPLES

Autonomy

The concept of informed consent may be derived directly from the principle of autonomy and from a desire to protect patients and research subjects from harm. There is general agreement that consent must be genuinely voluntary and made after adequate disclosure of information. As a minimum, when a patient consents to a procedure in health care, the patient should be informed about the expectation of benefit as well as the other reasonable alternatives and possible risks that are known. Table 1-1 provides a useful checklist (PREPARED) that expands on the minimum information required.

TABLE 1-1 THE PREPARED SYSTEM: A CHECKLIST TO ASSIST THE PATIENT AND PROVIDER IN THE PROCESS OF INFORMED CONSENT

| P | lan | The course of action being considered |

| R | eason | The indication or rationale |

| E | xpectation | The chances of benefit and failure |

| P | references | Cultural and patient-centered priorities (utilities) affecting choice |

| A | lternatives | Other reasonable options/plans |

| R | isks | The potential harm from plans |

| E | xpenses | All direct and indirect costs |

| D | ecision | Fully informed collaborative choice |

Modified from Reiter RC, Lench JB, Gambone JC: Consumer advocacy, elective surgery, and the “Golden Era of Medicine.” Obstet Gynecol 74:815, 1989.

Justice

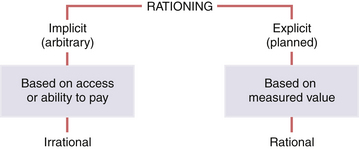

Justice relates to the way in which the benefits and burdens of society are distributed. The general principle that equals should be treated equally was espoused by Aristotle and is widely accepted today, but it does require that one be able to define the relevant differences between individuals and groups. Some believe all rational persons to have equal rights; others emphasize need, effort, contribution, and merit; still others seek criteria that maximize both individual and social utility. In most Western societies, race, sex, and religion are not considered morally legitimate criteria for the distribution of benefits, although they too may be taken into account to right what are perceived to be historical wrongs, in programs of affirmative action. When resources are scarce, issues of justice become even more acute because there are often competing claims from parties who appear equal by all relevant criteria, and the selection criteria themselves become a moral issue. Most modern societies find the rational rationing of health-care resources to be appropriate and acceptable (Figure 1-2).

Health-Care Quality Improvement

Health-Care Quality Improvement

PRACTICING MORE EFFECTIVELY

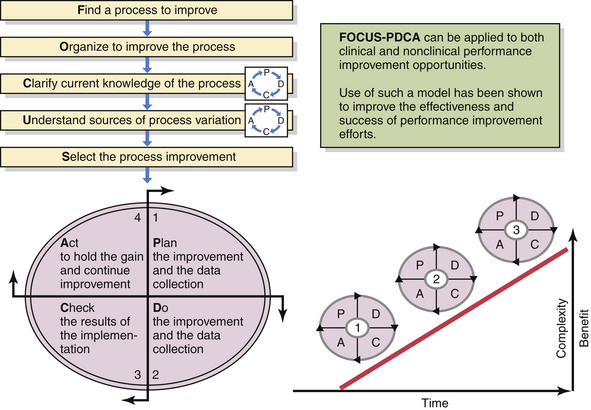

Paralleling the evolving science of outcomes assessment is the evolving science of outcomes improvement. Health-care organizations have adapted successful models of continuous quality improvement from industry as well as newer research or “evidence-based” models of care. Adoption of “best practice” models of care must be based on continuous reassessment of evolving practice, research, and innovation. Methods such as the FOCUS-PDCA cycle (Figure 1-3), originally developed at Bell Laboratories to test small incremental changes, have been applied to health-care processes and used successfully for continuous quality improvement programs. Use of such a standardized method has been shown to improve the effectiveness of clinical improvement efforts and accelerate the pace of needed change. Several other key clinical improvement tools are highlighted below.

Focus on Prevention

Focus on Prevention

The prevention and mitigation of existing disease has become an extremely important and sometimes overlooked area of effective practice. The famous American humorist, Will Rogers, said many years ago that people should only pay their doctors when they are well and not sick. This suggests a frustration that he was reflecting publicly that medical practice has neglected the promotion of wellness. As health-care treatment becomes more expensive and complex, there is a greater incentive for government, private industry, and individuals to invest in preventive services. The wise students of medical practice, including obstetrics and gynecology, will benefit from more education and training in prevention—and so will their patients. Box 1-1 contains a life-course perspective of early, effective prevention opportunities.

One recent example of a preventive intervention that is available in gynecologic practice is the vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection to prevent cervical cancer (see Chapters 22 and 38). This new technology illustrates both the promise of prevention and the controversy that can surround the use of some preventive measures.

IMMUNIZATIONS AND PREVENTIVE HEALTH SCREENING

Because public health recommendations for immunizations may change, it is best to check a reliable source periodically (e.g., www.cdc.gov) for the latest information before counseling patients. General recommendations include the following for women aged 19 to 49 years: measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), hepatitis B, and varicella for women who are nonimmune. Additionally, vaccination against HPV is currently recommended for girls and women aged 11 to 26 years, and a single dose of tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) for adults 19 to 64 years of age is now recommended to replace the next booster dose of tetanus and diphtheria toxoids (Td) vaccine. Influenza vaccine is recommended annually for all women older than age 50 years and for women aged 19 to 49 years who are health-care workers, who have chronic illnesses such as heart disease or diabetes mellitus, or who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant during the flu season. Pneumococcal vaccine is recommended for all women aged 65 years and older, for those with chronic illness or alcoholism, and for those who are immunosuppressed. Meningococcal and hepatitis A vaccines may be indicated in some women with risk factors. Remember that MMR, varicella, and HPV vaccines are contraindicated during pregnancy.

Table 1-2 contains recommended preventive health screening procedures for women.

| Intervention/Procedure | Risk |

|---|---|

| Pap smear annually from age 21 yr or sexual activity; after three consecutive normal smears, every 2 to 3 yr in low-risk women from age 30 until 70 yr | Cervical dysplasia/cancer |

| Mammography every other year from age 40 yr and then annually from age 50 to 70 yr | Breast cancer |

| Smoking cessation counseling, warning second-hand smoke exposure | Lung cancer, heart disease, other health risks associated with smoking |

| Height and weight measurement | Overweight and obesity |

| Regular blood pressure screening (every 2 yr) | Hypertension and stroke |

| Cholesterol/lipid profile every 5 yr until age 65 yr | Heart disease |

| Total skin inspection and selective biopsies | Skin cancer (sun exposure) |

| Diet and exercise counseling | Osteoporosis, fracture, and deformity |

| Blood sugar study with family history, obesity, or history of gestational diabetes | Diabetes mellitus; other comorbidities associated with obesity |

| Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy every 3 to 5 yr after age 50 yr | Colorectal cancer |

| Cervical sampling for Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, syphilis, and HIV based on history | Sexually transmitted infections |

| PPD of tuberculin for high-risk women | Tuberculosis |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; Pap, Papanicolaou test; PPD, purified protein derivative.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Ethical decision making in obstetrics and gynecology. Ethics in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2004.

Bateson P., Barker D., Clutton-Brock T., et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature. 2004;430:419-421.

Gambone J.C., Reiter R.C. Elements of a successful quality improvement and patient safety program in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:129-145.

Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of National Academy of Sciences, 1999.

President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry. Quality first: Better health care for all Americans. Retrieved January 1, 2008, from http://www.hcqualitycommission.gov/final.

Conclusions

Conclusions