Problem 18 A lady with diarrhoea and abdominal pain

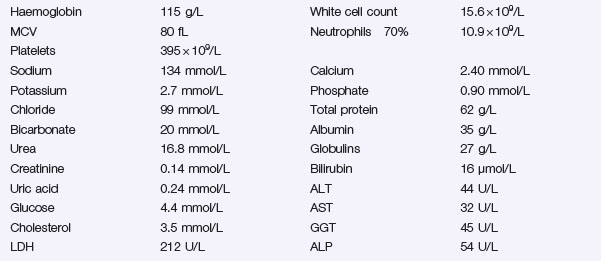

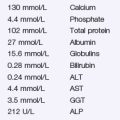

You prescribe loperamide. Blood tests are shown below. An abdominal X-ray is shown in Figure 18.1. Stool microscopy and culture are negative.

She is reviewed by the gastroenterologist and started on steroids.

She is reviewed by a dietician who starts a feeding programme.

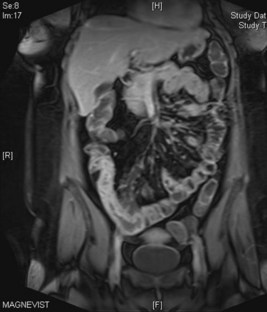

She is followed up for several years and her symptoms remain controlled. At a clinic appointment 3 years later she has developed abdominal pain and bloating after eating. This is sometimes accompanied by vomiting. The gastroenterologist sends her for a scan (shown in Figure 18.2).

Answers

Diarrhoea can be divided into acute or chronic. Acute is classified as lasting less than 14 days. It is usually secondary to infection which can be further subdivided by the presence of blood as shown in Table 18.1 below.

| Acute Diarrhoea With Blood | Acute Diarrhoea Without Blood |

|---|---|

| Shigellosis | Viruses |

| Escherichia coli 0157 | Escherichia coli |

| Campylobacter | Cholera |

| Salmonella | Protozoa |

| Amoebic dysentery | Strongyloides |

| Antibiotic associated diarrhoea | Food toxins |

| Schistosoma (rarely) | Malaria |

| Milder infection with Shigella/Salmonella/Campylobacter |

Infections are often self-limiting and rarely require antibiotics.

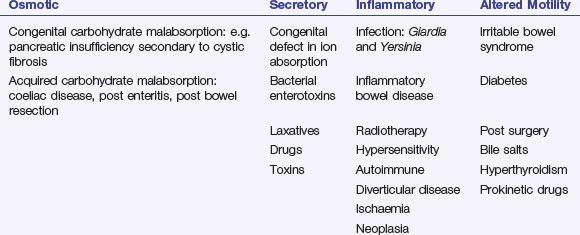

Chronic diarrhoea can be classified by its pathophysiology. There is overlap between aetiologies (Table 18.2):

A.2 Key questions when assessing patients with diarrhoea are:

It is often difficult to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease clinically. Clues in the clinical presentation are given in Table 18.3.

Table 18.3 Differentiating ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

| Feature | Crohn’s Disease | Ulcerative Colitis |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weight loss | Bloody diarrhoea with mucus, urgency, tenesmus |

| Signs | Fever, fistulae, perianal disease,abdominal masses | Fever, abdominal tenderness |

| Extra-intestinal | Oral ulceration, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, scleritis, episcleritis, uveitis, gallstones, pauciarticular arthropathy, DVT | Oral ulceration, erythema nodosum, episcleritis, uveitis, gallstones, pauciarticular arthropathy, DVT, primary sclerosing cholangitis |

A.9 Medical treatments for Crohn’s disease include:

If the above fail, use both approaches.

Adverse effects of these agents include:

This scan shows extensive Crohn’s disease in the terminal ileum, with luminal narrowing.

Malabsorption can result in deficiency of the following:

There is also an increased risk of colon cancer in patients with longstanding Crohn’s colitis.

Revision Points