Chapter 3 A Hierarchy of Healing: The Therapeutic Order

A Unifying Theory of Naturopathic Medicine

A Brief History of Naturopathic Medicine

A Brief History of Naturopathic Medicine

The modern naturopathic profession originated with Lust, and it grew under his tireless efforts. He crisscrossed the United States lecturing and lobbying for legislation to license naturopathy, testifying for naturopaths indicted for practicing medicine without a license, and traveling to many events and conferences to help build the profession. He also wrote extensively to foster and popularize the profession, and through his efforts, the naturopathic profession grew rapidly.1–3 By the 1940s, naturopathic medicine had developed a number of 4-year medical schools and had achieved licensure in about one third of the United States, the District of Columbia, four Canadian provinces, and a number of other countries.2,4

The profession went through a period of decline, marked with internal disunity and paralleled by the rise of biomedicine and the promise of wonder drugs. By 1957, there was only one naturopathic college left. By 1975, only eight states still licensed naturopathic physicians, and by 1979, there were only six. A survey conducted in 1980 revealed that there were only about 175 naturopathic practitioners still licensed and practicing in the United States and Canada.5 In contrast, in 1951, the number was approximately 3000.6

The decline of naturopathic medicine after a rapid rise was due to several factors. By the 1930s, a significant tension developed within the profession regarding naturopathic practice, as did the development of unified standards and the role of experimental, reductionist science as an element of professional development.7,8 This tension split the profession of naturopathic physicians from within after the death of Lust in the late 1940s, at a time when the profession was subject to both significant external forces and internal leadership challenges. Many naturopathic doctors questioned the capacity for the reductionist scientific paradigm to research naturopathic medicine objectively in its full scope.7,9,10

This perception created mistrust of science and research. Science was also frequently used as a bludgeon against naturopathic medicine, and the biases inherent in what became the dominant paradigm of scientific reductionism made a culture of scientific progress in the profession challenging. The discovery of effective antibiotics elevated the standard medical profession to dominant and unquestioned stature by a culture that turned to mechanistic science as an unquestioned authority. The dawning of the atomic age reinforced a fundamental place for science in a society increasingly dominated by scientific discovery. In this culture, standard medicine, with its growing political and economic strength, was able to force the near elimination of naturopathic medicine through the repeal or “sunsetting” of licensure acts.1,2,11

In 1956, as the last doctor of naturopathy (ND) program ended (at the Western States College of Chiropractic), several doctors, including Drs. Charles Stone, W. Martin Bleything, and Frank Spaulding, created the National College of Naturopathic Medicine in Portland, OR, to keep the profession alive. However, that school was nearly invisible as the last vestige of a dying profession and rarely attracted as many as 10 new students a year. The profession was considered dead by its historic adversaries.

The culture of America, dominated by standard medicine since the 1940s, however, began to change by the late 1960s. The promise of science and antibiotics was beginning to seem less than perfect. Chronic disease was increasing in prevalence as acute infection was less predominant, and standard medicine had no “penicillin” for chronic diseases. In the late 1970s, scholars in family medicine proposed a biopsychosocial model of care in response to a prevailing perception of a growing crisis in standard medicine.12 The publication of Engel’s “The Need for a New Medical Model” in April 1977 signaled the founding of the field of family medicine based on a holistic philosophy and paralleled a broader social movement in support of alternative health practices and environmental awareness. Elements of the culture were rebelling against plastics and cheap synthetics, seeking more natural solutions. The publication of Rachael Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962, an indictment of chemical pesticides and environmental damage, marked a turning point in cultural thinking. In Silent Spring, Carson challenged the practices of agricultural scientists and the government and called for a change in the way humankind viewed the natural world.13 New evidence of the dangers of radiation, synthetic pesticides, and herbicides, as well as environmental degradation from industrial pollution, were creating a new ethic. Organic farming, natural fibers, and other similar possibilities were starting to capture attention. A few began seeking natural alternatives in medicine. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, enrollments at the National College of Naturopathic Medicine began to reach into the 20s. The 1974 class numbered 23 students. In 1975, the National College enrolled a class of 63 students.14 The profession was experiencing a resurgence.

One of Dr. Bastyr’s important legacies was to establish a foundation and a model for reconciling the perceived conflict between science and the deeply established healing practices and principles of naturopathic medicine. Kirchfeld and Boyle3 described his landmark contribution as follows:

Bastyr also saw a tremendous expansion in both allopathic and naturopathic medical knowledge, and he played a major role in making sure the best of both were integrated into naturopathic medical education.3,15

Bastyr met Lust on two occasions and was closely tied to the nature cure tradition of Kneipp through two influential women: his mother and his mentor, Dr. Elizabeth Peters, who studied with Father Kneipp. He effortlessly integrated the clinical theories and practices of naturopathy with the latest scientific studies and helped create a new and truly original form of modern primary clinical care within naturopathic medicine. He spent the twentieth century preparing the nature cure of the nineteenth century for entry into the twenty-first century.1,15 Today’s philosophical debates within the profession are no longer about science. They tend to center on challenges to the Nature Cure tradition. A current debate, for instance, is about the role of “green allopathy” within the profession: the tendency to use botanical medicine or nutritional supplements as a simple “green drug” or pharmaceutical replacement versus the importance of implementing the full range of healing practices derived from Nature Cure to stimulate health restoration alongside, or instead of, botanical medicine or nutritional supplements. Professional consensus appears strong that the full range of naturopathic healing practices must be retained, strengthened, and engaged in the process of education and scientific research and discovery in the twenty-first century.16–18

Original Philosophy and Theory

Original Philosophy and Theory

Through the initial 50-year period of professional growth and development (1896–1945), naturopathic medicine had no clear and concise statement of identity. The profession was whatever Lust said it was. He defined “naturopathy” or “nature cure” as both a way of life and a concept of healing that used various natural means of treating human infirmities and disease states. The “natural means” were integrated into naturopathic medicine by Lust and others based on the emerging naturopathic theory of healing and disease etiology. The earliest therapies associated with the term involved a combination of American hygienics and Austro-Germanic nature cure and hydrotherapy. Leaders in this field included Kuhne, Lindlahr, Trall, Kellogg, Holbrook, Tilden, Graham, McFadden, Rikli, Thomson, and others who wrote foundational naturopathic medical treatises or developed naturopathic clinical theory, philosophy, and texts to enhance, agree with, and diverge from Lust’s original work.19–27

1. “Return to Nature”—attend to the basics of diet, dress, exercise, rest, etc.

2. Elementary remedies—water, air, light, electricity

3. Chemical remedies—botanicals, homeopathy, etc.

4. Mechanical remedies—manipulations, massage, etc.

5. Mental/spiritual remedies—prayer, positive thinking, doing good works, etc.28

In the 1950s Spitler wrote Basic Naturopathy, a Textbook,9 and Wendel wrote Standardized Naturopathy.10 These texts presented somewhat different approaches; Spitler’s text emphasized theory and philosophy, whereas Wendel’s text was written, as evidenced by the title, to emphasize the standard naturopathic practices of the day, with an eye toward regulatory practice. In contrast, Kuts-Cheraux’s Naturopathic Materia Medica, written in the 1950s, was produced to satisfy a statutory demand by the Arizona legislature, but persisted as one of the few extant guides of that era. Practitioners relied on a number of earlier texts, many of which arose from the German hydrotherapy practitioners29–34 or the Eclectic school of medicine (a refinement and expansion of the earlier “Thomsonian” system of medicine)35–39 and predated the formal American naturopathic profession (1900). However, by the late 1950s, publications diminished. The profession was generally considered on its last gasp, an anachronism of the pre-antibiotic era.

During the process of winning licensure, naturopathic medicine was defined formally by the various licensure statutes, but these definitions were legal and scope-of-practice definitions, often in conflict with each other, reflecting different standards of practice in different jurisdictions. In 1965, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Dictionary of Occupational Titles40 presented the most formal and widespread definition. The definition was not without controversy. as it reflected one of the internally competing views of the profession, primarily, the nature cure perspective:

“Diagnoses, treats and cares for patients using a system of practice that bases treatment of physiological function and abnormal conditions on natural laws governing the human body. Utilizes physiological, psychological and mechanical methods such as air, water, light, heat, earth, phytotherapy, food and herbs therapy, psychotherapy, electrotherapy, physiotherapy, minor and orificial therapy, mechanotherapy, naturopathic corrections and manipulations, and natural methods or modalities together with natural medicines, natural processed food and herbs and natural remedies. Excludes major surgery, therapeutic use of x-ray and radium, and the use of drugs, except those assimilable substances containing elements or compounds which are components of body tissues and physiologically compatible to body processes for the maintenance of life.”40

This definition did not list drugs or surgery within the scope of modalities available to the profession. It defined the profession by therapeutic modality and was more limited than most of the statutes under which naturopathic physicians practiced,41 even in 1975, when there were only eight licensing authorities still active.

Modern Naturopathic Clinical Theory: The Process of Development

Modern Naturopathic Clinical Theory: The Process of Development

In 1987, the newly formed (1985) American Association of Naturopathic Physicians (AANP) began this task under the leadership of James Sensenig, ND (president) and Cathy Rogers, ND (vice president), appointing a committee to head the creation of a new definition of naturopathic medicine. The “Select Committee on the Definition of Naturopathic Medicine” succeeded in a 3-year project that culminated in the unanimous adoption by AANP’s House of Delegates (HOD) of a comprehensive, consensus definition of naturopathic medicine in 1989 at the annual convention held at Rippling River, OR.43–45 The unique aspect of this definition was its basis in definitive principles, rather than therapeutic modalities, as the defining characteristics of the profession. In passing this resolution, the HOD also asserted that the principles would continue to evolve with the progress of knowledge and should be formally reexamined by the profession as needed, perhaps every 5 years.43–48

In September 1996, the AANP HOD passed a resolution to review three proposed principles of practice that had been recommended as additions to the AANP definition of naturopathic medicine originally passed by the HOD in 1989. These three new proposed principles were rejected, and the AANP HOD reconfirmed the 1989 AANP definition unanimously in 2000. The results of a profession-wide survey conducted from 1996 to 1998 on these three new proposed principles demonstrated that although there was lively input, the profession agreed strongly that the original definition was accurate and should remain intact. The HOD recommended that the discussion be moved to the academic community involved in clinical theory, research, and practice for pursuit through scholarly dialogue.49–53 This formed the basis for further efforts to articulate a clinical theory. AANP members stated in 1987–1989 during the definition process: “These principles are the skeleton, the core of naturopathic theory. There will be more growth from this foundation.”45 By 1997, this growth in modern clinical theory was evident.

The first statement of such a theory was published in the AANP’s Journal of Naturopathic Medicine in 1997 in an article titled “The Process of Healing, a Unifying Theory of Naturopathic Medicine.”54 This article contained three fundamental concepts that were presented as an organizing theory for the many therapeutic systems and modalities used within the profession and were based on the principles articulated in the consensus AANP definition of naturopathic medicine. The first of these was the characterization of disease as a process rather than a pathologic entity. The second was the focus on the determinants of health rather than on pathology. The third was the concept of a therapeutic hierarchy.

This article also signaled the emergence of a growing dialogue among physicians, faculty, leaders, and scholars of naturopathic philosophy concerning theory in naturopathic medicine. The hope and dialogue sparked by this article was the natural next step of a profession redefining itself both in the light of today’s advances in health care and with respect to the foundations of philosophy at the traditional heart of naturopathic medicine. This dialogue naturally followed the discussions of the definition process and created a vehicle for emerging models and concepts to be built on the bones of the principles. The essence and inherent concepts of traditional naturopathic philosophy were carried in the hearts and minds of a new generation of naturopathic physicians into the twenty-first century—these modern naturopathic students and naturopathic physicians began to gather to articulate, redefine, and reunify the heart of the medicine.

This new dialogue was formally launched in 1996, when the AANP Convention opened with the plenary session: “Towards a Unifying Theory of Naturopathic Medicine” with four naturopathic physicians presenting facets of emerging modern naturopathic theory. The session closed with an open microphone. The impassioned and powerful comments of the naturopathic profession throughout the United States and Canada engaged in the vital process of deepening and clarifying its unifying theory. Dr. Zeff presented “The Process of Healing: The Hierarchy of Therapeutics”; Dr. Mitchell presented “The Physics of Adjacency, Intention, Naturopathic Medicine, and Gaia”; Dr. Sensenig presented “Back to the Future: Reintroducing Vitalism as a New Paradigm”; and Dr. Snider announced the Integration Project, inviting the profession to engage in it by “sharing a beautiful and inspiring anguish—the labor pains of naturopathic theory in the twenty-first century. We know what we have done, and we know there is much more…The foundation is laid. We are ready now for development and integration.”55

Days later, in September 1996, the Consortium of Naturopathic Medical Colleges (now the American Association of Naturopathic Medical Colleges [AANMC]) formally adopted and launched the Integration Project, an initiative to integrate naturopathic theory and philosophy throughout all divisions of all naturopathic college curricula, from basic sciences to clinical training. A key element of the project engaged the further development and refinement of naturopathic theory. The project was co-chaired by Drs. Snider and Zeff from 1996 to 2003. Steering members from all North American naturopathic colleges participated and contributed.45 Methods included professional and scholarly research, expert teams, symposiums, and training. The result was the fostering of systematic inquiry among academicians, clinicians, and researchers concerning the underlying theory of naturopathic medicine, bringing the fruits of this work and inquiry into the classroom and into scientific discussion.56

The Integration Project sparked a wide range of activities in all six ND colleges, resulting in all-college retreats to share tools, retreats for training of non-ND faculty in naturopathic philosophy, integration of a basic sciences curriculum, expert teams revision of core competencies across departments ranging from nutrition to case management and counseling, development of clinical tools and seminars for clinic faculty, creation of new courses, and the integration of important research questions derived from naturopathic philosophy into research studies and initiatives.57 The latest effort is the Foundations of Naturopathic Medicine Project (textbook and symposia series, www.foundationsproject.com) and its development and presentation of the educational module on Emunctorology, an essentially naturopathic science, during 2009 and 2010. This is a joint effort of faculty from several of our schools, led by Drs. Thom Kruzel and Stephen Myers.

North American core competencies for naturopathic philosophy and clinical theory were developed by faculty representing all accredited ND colleges in a landmark AANMC retreat in 2000. The AANMC’s Dean’s Council formally adopted these competencies in 2000 and recommended that they be integrated throughout curricula in all ND colleges. These national core competencies included the process of healing theory, Lindlahr’s model, and the hierarchy of therapeutics (the therapeutic order).58,59

Drs. Snider and Zeff and naturopathic theory faculty worked closely with other naturopathic faculty from AANMC colleges in a series of revisions. Drs. Snider and Zeff collaborated in 1998 to develop the hierarchy of therapeutics into the therapeutic order. The therapeutic order was subsequently explored and refined through a series of faculty retreats and meetings, as well as through experience with students and through student feedback. A key finding of the clinical faculty at Bastyr University was the emphasis on the principle “holism: treat the whole person” and respect for the patient’s own unique healing order and his or her values as a context for applying the therapeutic order to clinical decision making.60 The therapeutic order, or hierarchy of healing, is now incorporated into ND college curricula throughout the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. For example, an important international outgrowth of the profession’s development of theory is the adoption of the unified “Working Definition of Naturopathic Nutrition” in June 2003 by the Australian naturopathic profession (Box 3-1). The 3-year project, fostered by Dr. Stephen Myers, brought together nutrition faculty from naturopathic medicine colleges throughout Australia. The project was co-hosted by the Naturopathy and Nutrition panel, an independent group of naturopaths and nutrition educators whose mission is to foster and support the development of the science, teaching, and practice of naturopathic nutrition, and the School of Natural and Complementary Medicine at Southern Cross University. The definition evolved over two retreats attended by more than 40 faculty members involved in teaching nutrition as part of a naturopathic medicine education. It commenced as a general agreement within the group that there was a real and distinct difference between conventional nutritional concepts and naturopathic nutritional theory. General agreement was that the distinction between the two had to date been poorly defined and had been the source of dissonance between the naturopathic and science faculty within the colleges. The obvious next step was to define that difference to ensure that nutrition curriculum within naturopathic medicine colleges reflected the core elements of naturopathic nutrition. At the second retreat held in June 2003, the working definition was adopted with a recommendation that it be widely circulated within the naturopathic medicine profession to commence a dialogue aimed at both appropriate revision and broad adoption. This process created a much-needed consensus definition on naturopathic nutrition. This definition is based on the AANP defining principles and incorporates the therapeutic order theory.

BOX 3-1 Working Definition of Naturopathic Nutrition

Definition

Naturopathic nutrition is the practice of nutrition in the context of naturopathic medicine.

Core components of naturopathic nutrition are:

• A respect for the traditional and empirical naturopathic approach to nutritional knowledge

• The value of food as medicine

• An understanding that whole foods are greater than the sum of their parts and recognition that they have vitality (properties beyond physiochemical constituents)

• Individuals have unique interactions with their nutritional environments

Practice

• Behavioral and lifestyle counseling

• Diet therapy (including health maintenance, therapeutic diets, and dietary modification)

• Food selection, preparation, and medicinal cooking

• Therapeutic application of foods with specific functions

• Traditional approaches to detoxification

Data from Snider P, Payne S. Making naturopathic curriculum more naturopathic: agendas, minutes, 1999-2001. Clinic faculty task force on integration. Faculty development retreat, Bastyr University, 1999.

A Theory of Naturopathic Medicine

A Theory of Naturopathic Medicine

The elegance of this model, and the science behind it, has taken medicine to its highest point in history as a reliable vehicle to ease human illness, and its application has saved countless lives. The understanding of the physician, at least about the nature of pathology, has never been as complete. However, illness has a near-infinite capacity to baffle the physician. New diseases arise, such as human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and shifts occur in disease focus, such as the shift between 1900 and 2000 from acute infection to chronic illness as the predominant cause of death.61

Beyond these obvious changes, even with the current depth of understanding, the standard medical world often lacks the ability to effectively understand and cure chronic disease, and treatment tends to become a task of the management of symptoms and the attempt to reduce long-term damage and other consequences, rather than actual cure of the illness. So, even representing an apex of human achievement as it does, modern medicine is not without its weaknesses. Its greatest weakness is probably this inability to cure chronic illness as easily as it once cured pneumonia with penicillin or tuberculosis with streptomycin. Compounding the problem is the growing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant infections.62,63 Part of the reason for the failures within modern medical science is its mechanistic basis. Breaking the body down to its constituent parts has led to a fundamental ignorance of and disrespect for the wholeness of the individual, the natural laws of physiology governing health and healing, and particularly for all things spiritual (the transpersonal domains). Inherent in the dictum—diagnose and treat the disease—is the general neglect of the larger understanding that disease is a process conducted by and within an intelligent organism that is constantly attempting to heal itself, with disease manifestations often expressions of this self-healing endeavor. As noted by Pizzorno et al,64 this intelligent organism strives for optimal function and health. Human beings “…are natural organisms, our genomes developed and expressed in the natural world. The patterns and processes inherent in nature are inherent in us. We exist as a part of complex patterns of matter, energy, and spirit. Nature doctors have observed the natural processes of these patterns in health and disease and determined that there is an inherent drive toward health that lives within the patterns and processes of nature.”

Illness and Healing as Process

Illness and Healing as Process

Naturopathic medicine can be characterized by a different model than “identify and treat the disease.” “The restoration of health” would be a better characterization. Naturopathic physicians adopted the following elegantly brief definition of naturopathic medicine in 1989 in an AANP position paper: “Naturopathic physicians treat disease by restoring health.”44 Immediately a significant difference is made clear: standard medicine is disease based; naturopathic medicine is health based. Although naturopathic medical students study pathology with the same intensity and depth as standard medical students, as well as its concomitant diagnoses, the naturopathic medical student learns to apply that information in a different context. In standard medicine, pathology and diagnosis are the basis for the discernment of the disease “entity” that afflicts the patient, the first of the two steps of identifying and destroying the entity of affliction. In naturopathic medicine, however, disease is seen much more as a process than as an entity. Rather than viewing the ill patient as experiencing a “disease,” the naturopathic physician views the ill person as functioning within a process of disturbance and recovery, in the context of nature and natural systems. Various factors disturb normal health. If the physician can identify these disturbances and moderate them (or at least some of them), the illness and its effects abate, at least to some extent, if not totally. As disturbances are removed, the body can improve in function, and in doing so, health naturally improves. The natural tendency of the body is to maintain itself in as normal a state of health as is possible—this is the basis of homeostatic principles.65 The role of the physician facilitates this self-healing process.

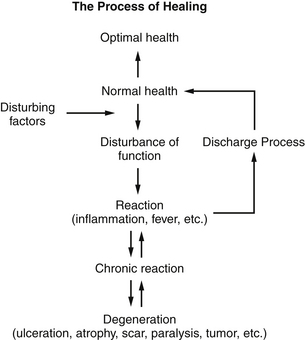

The obvious first task of the naturopathic physician, therefore, is to determine what is disturbing the health so that these causative elements may be ameliorated. Disease is the process whereby the intelligent body reacts to disturbing elements. It employs such processes as inflammation and fever to help restore its health. In general, one can graph this process simply, as in Figure 3-1.

The Naturopathic Model in Acute Illness

If the virus were the sole cause of the common cold, then everyone who came into contact with sufficient dose of the virus would get the cold. Obviously, this does not happen. Susceptibility factors include immune competence, fatigue, vitality, genetics, and other host factors.66 The virus enters a milieu in which all these factors affect the process. Once the virus enters the system, and if it overcomes resistance factors (Box 3-2), one begins to see disturbance of function, as illustrated in Figure 3-1. One does not feel quite right. One may begin to get a sore throat, the first inflammatory reaction, occurring at the point of entry of the virus into the body. The immune factors described may overcome the virus at this point, may be insufficient, or may be suppressed. All of this is mutable to some extent and is affected by host factors, such as nutritional status and fatigue, and can be influenced by taking immune tonics, vitamin C, and other supplements.

BOX 3-2 Scientific Considerations: The Immune Response and Resistance Factors

Once inside the body, the rhinovirus binds to cellular receptors (primarily the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 [ICAM-1]) or to the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor. The viral particles are then internalized and begin to take over the cellular machinery to produce intact virions.66,67 At this stage, the body can sometimes mount an adequate defense via cell-mediated immunity to overcome the viral incursion. If we have been previously exposed to the virus, the body’s humoral immune response will rapidly produce antibodies to the viral protein, which can also lead to eradication of the microbe. These two immune responses explain why some individuals may develop the full condition, whereas others will shake off the exposure within a few hours. If the viral load overcomes the body’s innate defenses, the virus replicates unabated. In the process of replication, the virus not only disrupts the cellular mechanisms, but damages them as well by infecting the surface epithelium, as well as the macrophages68 and fibroblasts.69 Naturopathic physicians are interested in the factors that lead to greater immune competence and health restoration through the process of healing and the health practices that support it. French physiologist Claude Bernard (1813–1878) said that the inner terrain or “milieu interieur” was the cause of disease, and not the microbes; this concept underpins the naturopathic approach.

In the naturopathic model, the virus is not understood so much to be a separate disease entity, but a general and fundamental process of disturbance and recovery within the living body. It is a method whereby the body restores itself after a sufficient amount of disturbance accumulates within the system. This is why the cold has no “cure.” It is the cure for what ails the body. In the naturopathic model of health, it is the support of this “adaptive response”—the restoration of balance that is the central point— through which the process is the “cure” (Box 3-3).

BOX 3-3 Scientific Considerations: Consequences of Suppressing the Body’s Response

Current research shows that future pathologies may be linked to “suppression” of early rhinovirus infection. These include childhood asthma, adult asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).70,71 Individuals with asthma are known to have subtle deficiencies in production of type I and type III interferon (IFN),72,73 indicating that for some asthma patients, early exposure to the rhinovirus predisposes them to asthma, and that the suppression of the normal response may be critical in the future development of asthma. With these effects in mind, the naturopathic physician does not look solely at the virus as a pathogenic entity, but also seeks to determine how the patient responds to the virus, thereby determining the most reasonable approach to aiding the patient’s natural responses and moderating the patient’s long-term health strategies. Suppression of the body’s natural responses is avoided. The long-term use of corticosteroids is a prime example of suppression and its consequences.74,75

The Naturopathic Model in Chronic Illness

Chronic illness arises, in general, when any or all of three factors occur:

1. The disturbing factors persist, such as a chronically improper diet, which continues to burden the body cumulatively, as the digestive processes slowly weaken under the stress of the improper or inadequate diet.

2. The reactive potential is blocked or suppressed, usually by drugs, which interfere with the capacity of the body to process and remove its disturbances.

3. The vitality of the system is insufficient, or has become too overwhelmed, to mount a significant and sufficient reaction.

As these three factors prevent a sufficient reactive purge of disturbances, the body slides into a chronic, weakened reactive state with possible episodes of intermittent reaction, and is perceived to be in a persistent chronic illness. Ultimately, as function is sufficiently disturbed, structures or functions are damaged, and chronic inflammation becomes ulceration or scar tissue formation. In terms of the allostatic model, the balance has been disrupted, and there is no more adaptive potential. Atrophy, paralysis, or even tumor formation76–78 may occur. All of this is the body manifestly doing the best it can for itself in the presence of persistent disturbing factors and with respect to the limitations and range of vitality influenced by the constitution, psycho-emotional/spiritual state, genotype of the person, and his or her surrounding environment (Boxes 3-4 and 3-5).

BOX 3-4 Scientific Considerations: The Role of Environment in Chronic Illness

Environmental and lifestyle disturbances are a profound driver in the naturopathic model of health. The scientific evidence is now irrefutable that the national and global burden of chronic disease is highly dependent on modifiable behavioral factors. In a recent study of the causes of death, it was found that tobacco, poor diet and lack of physical activity, alcohol and drug use, toxic agents, and vehicular and firearm incidents were the leading actual causes of death.79 Other factors included frank malnutrition (as opposed to poor nutrition), unsafe sexual practices, and poor sanitation.80,81 It has been definitively shown, for example, that diet and lifestyle changes can prevent some forms of diabetes82,83 and other chronic diseases84,85 that are leading causes of death in the United States.79,82,83

BOX 3-5 Scientific Considerations: Chronic Illness and the Adaptive Response

Regarding the responses of an overwhelmed or chronically disturbed organism, it has been argued recently that the anemia of chronic disease is an adaptive biological response rather than a harmful disorder and is associated with a number of chronic states.86 Citing a number of studies, it was also argued that it was the treatment of the anemia of chronic disease among critically ill patients and those with renal failure and cancer (e.g., breast cancer and head and neck cancers) that was associated with the greater mortality. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning against the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in those cancer patients not undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy.87

States where the normal compensatory mechanisms become overwhelmed or suppressed (reducing the reactive potential of the body) include states of chronic oxidative stress88 and inflammatory processes.89,90 It is not, however, solely a matter of an overwhelmed or chronically disturbed organism that is critical to the process of disease progression. Adaptive responses are also of vital importance to the development of chronic disease. Research has shown that these evolutionarily preserved adaptive mechanisms of physical activity, insulin sensitivity, and fat storage are essential in the prevention of chronic disease states.84,85 In the development of type 2 diabetes, for example, there is increasing evidence that it is the individual’s maladaptation to lack of physical activity that appears to lead to decreased insulin sensitivity and increased fat storage, which can then lead to a plethora of chronic diseases, many characterized by states of chronic inflammation91 and oxidative stress. Continuing basic and clinical studies indicate that many of the processes currently regarded in mainstream medicine as harmful have been evolutionarily retained to provide an adaptive advantage.92,93 The Harvard Health Letter recently published an article describing inflammation as part of the “Unifying Theory of Disease”94 giving support to the argument that inflammation is crucial in both health and disease and that chronic diseases arise when the inflammatory process occurs without appropriate control. The allostatic model also provides a theoretical basis for naturopathic clinical theory. The allostatic model describes the process of achieving stability (homeostasis) through changes in the homeostatic “set points” or control boundaries.95–98 Homeostasis, the maintenance of stability in biochemical and physiologic processes, is essential for life—and allostasis, the “re-setting” of the homeostatic “set points”, is essential for the maintenance of homeostasis. As it develops through the various iterations of researchers and clinicians, the model emphasizes the need to look beyond the current linear-reductionist model of disease and toward a more wholistic and balanced approach to disease conditions.

The adaptive response of the organism to insult or frank structural damage is a concept that also has support outside naturopathic medicine. For example, Schnaper et al99 described a conceptual framework for progressive kidney disease where the initial disease develops through an injury of some nature that provokes a cellular response as an adaptation to the original injury. Where this cellular response is effective, no progressive kidney disease may ensue. If, however, there is a maladaptation, these attempts at self-repair may lead to progressive loss of nephrons and chronic kidney disease.

Reversal of this overwhelmed condition is rarely accomplished by medicating the pathologic state. This often results in the control of symptoms but with the persistence of the illness, while ideally controlling its more dangerous aspects using higher force interventions such as pharmaceutical drugs and surgical intervention. Reversal is more likely accomplished by identifying and ameliorating the disturbance, and as necessary, strengthening or supporting the reactive potential. The first step in this process is to identify and reduce disturbing factors.

The Determinants of Health

The Determinants of Health

To reduce the disturbance, one must identify the disturbance. In standard medicine, the first step is to identify the pathology, which is then treated. In naturopathic medicine, one must come to understand what is disturbing the health. To do this, the physician needs to understand what determines health in the first place. The physician can then evaluate the patient in these terms and come to understand what is disturbing the natural state of health. Such a list could be created by any doctor, certainly any naturopathic physician. The authors propose using the list in Box 3-6.

BOX 3-6 Naturopathic Medicine Determinants of Health

Factors That Influence Health

How We Live – Hygienic, Lifestyle, Psycho-emotional, Spiritual, Socioeconomic & Environmental Factors

From Snider P, Zeff J, Myers S, DeGrandpre Z, et al. Course syllabus: NM5114, Naturopathic Clinical Theory. Seattle: Bastyr University, 1997-2012.

Some of these determinants have been discussed—those modifiable behavioral factors such as drug and alcohol use, poor diet or frank malnutrition, lack of physical exercise, environmental and socioeconomic factors, and unsafe sexual practices.79–81100 (Box 3-7). Many of these behavioral factors have major psychological and spiritual components, and the effect can be increased stress on both the individual and the family, with all its attendant consequences.100–102 The naturopathic physician evaluates the patient with these areas in mind, looking for aspects of disturbance, first in the spirit, and most generally in diet, digestion, and stress in its various aspects. In this evaluation, the naturopathic physician brings to bear a body of knowledge somewhat unique to naturopathic medicine to evaluate not solely in terms of pathologic entity, but in terms of normal function and subclinical functional disturbance (Box 3-8). By locating areas of abnormal function or disturbance, the naturopathic physician acts or recommends ways to ameliorate the disturbance.

BOX 3-7 Scientific Considerations: Subclinical Inflammation and Chronic Illness

It is becoming increasingly evident that many chronic diseases may have a long subclinical phase, most involving the inflammatory process. As mentioned, a chronic, subclinical inflammatory state has been linked to a number of disorders, including insulin resistance,104 obesity,105 vascular disease,106–109 hypertension,110 and aging.111

BOX 3-8 Scientific Considerations: Determinants of Health within Public and Community Health Concerns

There exists increasing consensus that Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis result from the combined effects of four important factors, none of which are individually sufficient to cause the disease. These four factors are the global changes in the environment, alterations in the microbiome of the intestine, multiple genetic factors, and aberrations or maladaptations in both the innate and adaptive immune systems.114–117 These four factors, considered to be vital to the development and the increased rates of irritable bowel disease, are quite similar to the Determinant of Health described in Box 3-6. This serves as a further example of the growing appreciation for the similarities (with important differences) between naturopathic medicine and public and community health.

As disturbing factors or insults to the system are reduced, the natural tendency of the system is to improve and optimize its function, directing the system back toward normalcy, or homeostasis. In more conventional medical terms, this is one of the fundamental concepts of the allostatic model.95–98101 In naturopathic thinking, this is the removal of the obstacles to cure, which allows the emerging action of the vis medicatrix naturae, the vital force, the healing power of nature. This is the first step in the hierarchy of healing and what naturopathic physicians may call the overarching model in the clinical theory (the process of healing) of naturopathic medicine: the therapeutic order. This process can be seen in the naturopathic model of healing in Figure 3-1.

Therapeutic Order

Therapeutic Order

The therapeutic order is a natural hierarchy of therapeutic intervention based on, or dictated by, observations of the nature of the healing process from ancient times through the present.112 “Therapeutic orders” also exist in traditional Chinese, Tibetan, Ayurvedic, and Unani medicine theories. It is a natural ordering of the modalities of naturopathic medicine and their application. The concept is somewhat plastic, in that one must evaluate the unique needs, and even the unique healing requirements, of the specific patient or situation.113 However, in general, the nature of healing dictates a general approach to treatment. In general, this order is listed in Box 3-9.

BOX 3-9 The Therapeutic Order: Hierarchy of Healing

7. Suppress or surgically remove pathology

Acute and chronic concerns are both addressed using the therapeutic order.121 Acute concerns are addressed first to avoid further damage, risk, or harm to the patient. The point of entry for assessment and therapy is dependent on each patient’s need for effective, safe care, healing, and prevention of suffering or degeneration.1,121

From Zeff J, Snider P. Course syllabus: NM5131, Naturopathic clinical theory. Seattle: Bastyr University, 1997-2005.

An analogy for the therapeutic order in Australian standard medicine is what is called the “softer option” model of patient care.118 This model recognizes that, given a choice, the patient will generally choose the softer option, provided that this does not limit a harder option, if the softer option fails. By way of example, given a choice between an antibiotic and amputation for a minor cut finger, most people would choose the softer option. Expanding this range of choice to an herbal cream, antiseptic (herbal or nonherbal) and a Band-Aid, an antibiotic, or amputation, we develop a therapeutic order ranging from the softest option (the least force) to the hardest option (the higher force intervention). The therapeutic order can be seen as a progression of therapeutic interventions that begin with this “softer option.”

Acute and Chronic Concerns

As discussed previously, there is an inherent drive toward health that is observable within the patterns and processes of nature. The drive is not perfect. There are times when unguided, unassisted, or unstopped, the drive goes astray, causing preventable harm or even death in patients; the constructive healing intention119 becomes destructive pathology. The ND is trained to know, respect, and work with this drive in both acute and chronic illness, using the therapeutic order, and to know when to wait or do nothing, act preventively, assist, amplify, palliate, intervene, manipulate, control, or even suppress using the principle of the least force.120 Acute and chronic concerns are both addressed and managed using the therapeutic order.121 Acute concerns are addressed first to avoid further damage, risk, or harm to the patient. The point of entry for assessment and therapy is dependent on each patient’s need for effective, safe care, healing, and prevention of suffering and degeneration.64,121

Naturopathic physicians avoid suppression of symptoms in acute circumstances unless necessary for patients’ well-being and safety. Instead, wherever possible, therapies for acute concerns use the least force (minimizing toxic side effects, suppression of natural functions, and physiologic burdens) available to intervene effectively, healing or palliating as needed. The full range of modalities from nutrition to homeopathy, botanical and physical medicine, hydrotherapy, counseling, prescriptive medication, and surgery are available to the patient as the naturopathic physician works to apply the least force in providing effective preventive, acute, and chronic care.121

Establish the Conditions for Health

Identify and Remove Disturbing Factors

Among these many possibilities, in general, the most significant are attitude diet, digestion, psychological and other stressers, and what might be called “spiritual integrity.” Humans have a transpersonal dimension and can be seen as spiritual beings. Spirit here is not defined by religion or belief in a deity or deities; it is that component of the individual that gives rise to their inner compass, their “joie de vivre” and their internal meaning of life, their core beliefs, and their values. Perceived in this way, it can be seen that many people in society are experiencing “spiritual crises.”86 Although the general purview of the physician is the body, that instrument cannot be separated from the spirit that animates it. If the spirit is disturbed, the body cannot be fundamentally healthy. Hahnemann, the brilliant and insightful founder of homeopathy, instructed physicians to attend to the spirit.122 Disturbance in the spirit permeates the body and eventuates in physical manifestation. Physicians are responsible for perceiving such disturbances and addressing them. At colleges of naturopathic medicine in Australia, the United Kingdom, and North America, faculty work with naturopathic medicine students to develop their ability to perceive the spiritual nature of an individual as a foundational skill in addressing the spiritual crises or fundamental needs that have a profound effect on health and well-being. Using this definition, both atheists and agnostics can be seen to have a spiritual aspect. This definition also removes spirituality from religiosity in a way that does not denigrate any individual religious belief a patient may hold, allowing the naturopathic clinician to explore this aspect of the individual.

One of the oldest concepts in naturopathic medicine is the concept of toxemia. Toxemia is the generation and accumulation of metabolic wastes and exogenous toxins within the body. These toxins may be the results of maldigestive processes, intermediate metabolites, environmental xenobiotics, colon bacterial metabolites, etc. These toxins become irritants within the body, resulting in the inflammation of tissues and the ultimate interference with normal biochemical processes.123 The maldigestive and dysbiotic124,125 origin of these internally and externally derived toxins is the result of an inappropriate diet, broad spectrum antibiotics, and the effects of excessive stress on digestion.126 Eating a diet that cannot be easily digested or that is out of appropriate nutrient balance for the individual results in the creation of metabolic toxins in the intestines.124,125–127 Stress, causing the excessive secretion of cortisol and adrenalin, results in the decrease of blood flow to the digestive process, among other effects,95–98101 which decreases the efficient functioning of digestion and increases the tendency toward maldigestion, dysbiosis, and toxemia. Physicians can now easily measure the degree of toxemia in various ways (urinary indican or phenol127). The older concept of toxemia,129,130 with scientific advances in its understanding121,129 (Box 3-10), may now be productively combined with understanding of the newer concept of allostasis95–98 and the historical119,130 and re-emerging discussion on the inflammatory component of many, if not most, chronic diseases.* Spiritual disharmony, inappropriate diet, digestive disturbance, stress, and toxemia (leading to inflammation) are considered primary causes of chronic illness and must be addressed if healing is to occur. Beyond these, other disturbing factors must be discerned and addressed, whichever pertain to the individual patient.

BOX 3-10 Scientific Considerations: Toxemia Today

Using conventional medical terminology, environmental, dietary, and lifestyle derived disorders are termed idiopathic environmental intolerances, multiple chemical sensitivities,127,128,132,133 or sometimes oxidative stress disorders.134–138 The terminology may be different, but it describes the same symptomatology. Environmental toxins accumulate, and chronic inflammation increases. These exogenous and endogenous toxins and the lack of exercise stress the system further. The ketogenic diet to control epilepsy may be considered one example of the successful application of diet to control symptoms.103

Institute a Healthier Regimen

As a corollary of the first, once physicians have determined major contributing factors to illness, they construct a healthier regimen for the patient. Some disturbing factors can be eliminated, like inappropriate dietary elements.82,83 Others are a matter of different choices or living differently.† The basics to consider are appropriate diet, appropriate rest and exercise, stress moderation, a healthy environment, and a good spiritual connection.

The same is true with these other fundamental elements, to which Lindlahr referred in the first element of his catechism, “return to nature”: exercise, rest, dress, etc.28 These have been expanded in the “determinants of health.” They create the basis for improvement. What this really means is to change the “terrain,” the conditions in which the disease has formed—not only to change but to improve the conditions so that there is less basis for the disease. Hahnemann addresses this on the first page of his Organon of Medicine.122 He identified four tasks for the physician: to understand the true nature of illness, “what is to be cured”; to understand the healing potential of medicines; to understand obstacles to recovery and how to remove them; and to understand the elements that derange health and how to correct them so that recovery may be permanent.122 Changing and improving the terrain in which the disease developed is the obvious first step in bringing about improvement. This sets up the basis for the following elements to have the most beneficial effects.

Stimulate the Self-Healing Mechanisms

A certain percentage of patients improve sufficiently simply by removing disturbing factors and establishing a healthier regimen. Most require more work. Once the patient is prepared, once the terrain is beginning to clear of disturbing factors, then one begins to apply stimulation to the self-healing mechanisms. The basis of this approach is the underlying recognition of the vis medicatrix naturae, the tendency of the body to be self-healing, the wisdom and intelligence within the system that constantly tends toward the healthiest expression of function, and the healing “forces” in the natural environment (air, water, light, etc.). The body heals itself. The physician can help create the circumstances to promote this. Then, as necessary, the physician stimulates the system. This also requires that attention be given to the patient’s emotional state of mind, because the psychological condition of the patient is often of major importance.140,141

One of the best ways to do this is through constitutional hydrotherapy, as developed by Otis G. Carroll, ND, early in the past century. This procedure is simple, involving the placement of hot and then cold towels on the trunk and back, in specific sequence (depending on the patient), usually accompanied by a sine wave stimulation of the digestive tract. This is a dynamic treatment, simple, inexpensive, and universally applicable. It helps recover digestive function, stimulates toxin elimination, “cleans the blood,” enhances immune function, and has several other effects. It moves the system along toward a healthier state.142 Exercise often achieves similar results. Many naturopathic modalities can be used to stimulate the overall vital force.

More specific approaches to stimulation, although general in effect, are applied differently to each patient and have a less general effect than those previously mentioned. Homeopathy and acupuncture143–145 are often the primary methods of such stimulation. They add little to the system; they are not gross chemical treatments. They work with what is there, stimulating a reaction, stimulating function, and correcting disturbed patterns.

Finally, exposure to the patterns, rhythms, and forces of nature is a traditional part of naturopathic medicine and the tradition of nature doctors throughout the world. As previously noted, “We exist as part of complex patterns of matter, energy, and spirit,”1 and the natural progression of these patterns and the drive toward health inherent in them, is a natural ally for the physician. Exposure to appropriate rhythms, patterns, and forces of nature strengthens vitality and stimulates the healing power of nature.

Support Weakened or Damaged Systems or Organs

Some systems or functions require more than stimulation to improve. Some organs are weakened or damaged (e.g., adrenal fatigue after prolonged stress), and some systems are blocked or congested (e.g., the hepatic detoxification pathways) and require extra help. This is where naturopathic physicians use their vast natural medicinary. Botanical medicines can affect any system or organ, enhancing its function, improving its circulation, providing specific nutrition, and stimulating repair. Glandular substances can be applied to a similar purpose. Plus, there are the growing number of evidence-based “nutraceuticals”—biological compounds that enhance metabolic pathways and provide substance for metabolic function.146–157

Naturopathic physicians can also apply specific homeopathic medications, usually in the lower potencies, which act nutritively and can stimulate specific organs or functions. This method, generally referred to as drainage, can be used to stimulate detoxification of specific substances from the body in general or of specific organ systems or tissues. Dr. Pizzorno’s work in Total Wellness,158 the work of “functional medicine” leader Jeffrey Bland, PhD, and the Textbook of Functional Medicine by Jones120 exemplify the clinical strategies applied at this level of the therapeutic order. These strategies are used to restore optimal function to an entire physiologic system (immune, cardiovascular, detoxification, life force, endocrine).158

Address Structural Integrity

Many structural problems result from generalized stress of some kind on internal systems. For example, mid-back misalignment or discomfort (T1–T12) is often found associated with a history of underlying stress on the digestive organs, the enervation of which originates at those spinal segments. One can manipulate the vertebra back into proper alignment or massage contracted musculature, but until one corrects the underlying functional disturbance, there will be a tendency to repeated structural misalignment. In some circumstances, the singular problem may be simply structural disintegrity. One may have fallen or been hit in some fashion and simply needs the neck manipulated back into proper alignment and the surrounding soft tissue relaxed. There may be no dietary error or other disturbance aside from the original injury, and correction requires only simple manipulation or therapeutic massage. This is an example of the flexibility of the therapeutic order concept. In this case, first-order therapeutics manipulate the cervical spine or relax chronically contracted muscles. Usually, however, the problem of structure is part of the larger problem, and such intervention becomes a fourth-order therapeutic.64

Address Pathology: Use Specific Natural Substances, Modalities, or Interventions

It is easy to do this. The culture is accustomed to this model and often expects to encounter this in the naturopathic physician’s office. In some states, such as Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, where the naturopathic formulary includes most antibiotics and many pharmaceutical drugs, one can practice almost without distinction from a medical doctor. The typical naturopathic formulary is often sufficient to prescribe on a strictly pathologic basis.

Given all of this, it still may be useful to directly address the pathologic entity or its etiology.159–163 When treating an antibiotic-resistant infection, for example, it may be useful to apply botanical medicines with specific antibiotic properties, along with immune tonics and the more fundamental steps of this therapeutic hierarchy. In difficult cases, such as many cancers, using agents that have specific, pathology-based therapeutics may be an essential element of comprehensive treatment. The naturopathic formulary provides a vast and increasing number of such options. One advantage of such treatment is that, in general, when applied by a knowledgeable practitioner, it rarely adds more burden or toxicity to the system. Naturopathic pathology-based treatments still follow the dictum “do no harm.”

Suppress Pathology

Sometimes it is necessary when there is risk of harm to the patient’s health or tissue, or to relieve suffering, to suppress pathology. Medical doctors are especially trained in this art and have powerful and effective tools with which to do this. Unfortunately, suppression, because it does not fundamentally remove or address essential causative factors (such as dietary error) often results in the development of other, often deeper disturbance or pathology. Because much pathologic expression is the result of the actual self-healing mechanisms (e.g., inflammation), suppressive measures are, in general, anti–vis medicatrix naturae. The result of suppression is that the fundamental disturbing factors are still at play within the person, still disrupting function to some extent, whereas the suppression reduces the symptomatic expression and resolution of disturbance. One simple example of this is the over use of corticosteroidal anti-inflammatory and antihistaminic drugs in the treatment of acute asthma. This usually effectively opens the airways. However, prolonged use weakens the patient. If the treatment persists, the patient becomes immune compromised and osteoporotic and can develop psychological disorders. These symptoms are part of the long-term effects of steroids.74 It may necessarily maintain breathing, but the long-term cost to the organism is high.

Theory in Naturopathic Medicine

Theory in Naturopathic Medicine

The consensus definition of naturopathic medicine, adopted by the AANP in 1989, is a statement of identity, distinguishing naturopathic medicine from other systems of medical thought. Contained within it is a set of instructions regarding the practice of the medicine. The three concepts discussed here—“disease as process,” “the determinants of health,” and “the therapeutic order”—are an articulation of these instructions. They are presented as a clinical theory of naturopathic medicine. They have been crystallized, as is the definition, from the observation by nature doctors throughout time and across many traditions of the nature of health, disease, and healing. They provide the physician with instructions. These instructions include a procedure for thinking about human illness in such a way that one can approach its cure in an ordered fashion by understanding its process as an expression of the vis medicatrix naturae. It provides the framework for truly evaluating the patient as a whole being: spiritual, mental/emotional, and physical, rather than as a category of pathology. Plus, it provides the physician a system for organizing and efficiently integrating the vast therapeutic array provided in naturopathic medicine. Ultimately, it satisfies Hahnemann’s observation of the ideal role of medicine, that “the highest ideal of cure is rapid, gentle and permanent restoration of the health … in the shortest, most reliable and most harmless way, upon easily comprehensible principles.”122 The roots of the observations that form this theory are traceable through the mid- and early-twentieth century, to the traditional theory of nineteenth-century European nature cure, and to the roots and theories of traditional world medicines. Hippocrates’ writings on the vis medicatrix naturae form a foundation that historically underpins the development of this theory.164,165

Although this presentation is not comprehensive, the attempt has been made to demonstrate these roots, at least in some of their major articulations. The work presented here is a continuation of this historical process, which ultimately is driven by the true mission of the physician: to ease suffering and to preserve life.

1. Pizzorno J., Snider P. Naturopathic medicine. In: Micozzi M.S., ed. The fundamentals of complementary and alternative medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

2. Cody G. The history of naturopathic medicine. In: Pizzorno J., Murray M. Textbook of natural medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

3. Kirchfeld F., Boyle W. The nature doctors: pioneers in naturopathic medicine. Portland, OR: Medicina Biologica; 1994.

4. Schramm A., ed. Yearbook of the International Society of Naturopathic Physicians and Emerson University Research Council, April 1945.

5. Tribe W. Personal communication. National college professional survey Portland, OR, National College of Naturopathic Medicine, 2008.

6. Wendel P. Standardized naturopathy. Brooklyn, NY: Paul Wendel; 1951.

7. Kirchfeld F., Boyle W. Nature doctors. East Palestine, OH: Buckeye Naturopathic Press; 1994. 202-208, 258-260

8. Freibott G. Report submitted to Lanso Cavasos, secretary of education. U.S. Department of Education. 1990.

9. Spitler H.R. Basic naturopathy, a textbook. New York: American Naturopathic Association; 1948.

10. Wendel P. Standardized naturopathy. Brooklyn, NY: Paul Wendel; 1951.

11. Coulter H. Divided legacy: a history of the schism in medical thought. Washington DC: Wehawken Book Company; 1973.

12. Engel G.L. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136.

13. Lear L. Rachel Carson biography. Available online at http://www.wilderness.net/index.cfm?fuse=feature0407 Accessed 8/10/2011

14. Enrollment records. National College of Naturopathic Medicine. Accessed 6/20/2004.

15. Kirchfeld F., Boyle W. The nature doctors: pioneers in naturopathic medicine. Portland, OR: Medicina Biologica; 1994. 310-312

16. Snider P. The future of naturopathic medical education—primary care integrative natural medicine: the healing power of nature. In: Cronin M., ed. Best of naturopathic medicine: anthology 1996: celebrating 100 years of naturopathic medicine. Tempe, AZ: Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine Publications, 1996.

17. Snider P. Integration project survey results: report to the AANMC dean’s council: 1999. Database: Snider P, Monwai M.

18. Standish L., Calabrese C., Snider P., et al. Naturopathic medical research agenda: report to NCCAM: Draft, 2004;5.

19. Tilden J.H. Toxemia explained: an antidote to fear, frenzy, and the popular mad chasing after so-called cures: the true interpretation of the cause of disease, how to cure is an obvious sequence, Rev. ed. Denver: FJ Wolf; 1926.

20. Trall R. The true healing art. New York: Fowler & Wells; 1880.

21. Graham S. Greatest health discovery: natural hygiene & its evolution past, present & future. Chicago: Natural Hygiene Press; 1860.

22. Kellogg J. Rational hydrotherapy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co; 1903.

23. Kuhne L., Lust B. Neo-naturopathy: the new science of healing or the doctrine of the unity of diseases, 1917. Butler, NJ

24. Kuhne L., Lust B. The science of facial expression: the new system of diagnosis, based on original researches and discoveries, 1917. Butler, NJ

25. McFadden B. MacFadden’s encyclopedia of physical culture, vol 5. New York: Physical Culture Publishing. 1920.

26. Rikli A. Die Grundlerhren der Naturheilkunde einschliesslich “Dia atmospharische Kure,” “Es werde Licht” und “Abschiedsworte” [The Fundamental Doctrines of Nature Cure including “the Atmospheric Cure,” “Let There Be Light” and “Words of Farewell”], 9th ed. Wolfsberg, Germany: G. Rikli; 1911. [in German]

27. Tilden J.H. Impaired health: its cause and cure—a repudiation of the conventional treatment of disease, 2nd ed. Denver: Tilden; 1921.

28. Lindlahr H. Nature cure: philosophy and practice based on the unity of disease and cure. Chicago: Nature Cure Publishing; 1913.

29. Kneipp S. Thus shalt thou live. Kempten, Bavaria: Koesel; 1889.

30. Kneipp S. My water cure. UK: Thorsons; 1979. [reprint of 1891 edition]

31. Kneipp S. My will. Kempten, Bavaria: Koesel; 1894.

32. Trall R.T. Hydropathic encyclopedia: a system of hydropathy and hygiene. New York: Fowlers & Wells; 1851.

33. Rausse J.H. Der Geist der Graffenberger Wasserkur. Zeitz: Schieferdecker; 1838.

34. Rikli A. Die Thermodiatetik oder das tagliche thermoelectrische Licht und Luftbad in Verbindung mit naturfemasser Diat als zukunftige Heilmethode. Vienna: Braumueller; 1869.

35. Thomson S. A brief sketch of the causes and treatment of disease. Boston: EG House; 1821.

36. Beach W. A treatise on anatomy, physiology and health. New York: W. Beach; 1847.

37. Ellingwood F. American materia medica, therapeutics, and pharmacognosy. Evanston: Ellingwood’s Therapeutist; 1919.

38. Felter H. The eclectic materia medica, pharmacology, and therapeutics. Cincinnati: John K Scudder; 1922.

39. Boyle W. The herb doctors. East Palestine, OH: Buckeye Naturopathic Press; 1988.

40. Dictionary of Occupational Titles. vol 1, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 1965.

41. Schram A. Acts and laws. In: Yearbook of the International Society of Naturopathic Physicians & Emerson University Research Council. Los Angeles: International Society of Naturopathic Physicians; 1945. 1948

42. Bradley R. Philosophy of naturopathic medicine. In: Pizzorno J., Murray M. Textbook of natural medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

43. AANP House of Delegates Resolution, 1989. Rippling River, OR

44. Select Committee on the Definition of Naturopathic Medicine. Snider P, Zeff J, co-chairs. Definition of naturopathic medicine: AANP position paper. Rippling River, OR: 1989.

45. Select Committee on the Definition of Naturopathic Medicine, AANP 1987-1989. Report submitted to AANP in 1988, final recommendation submitted to AANP House of Delegates, September 1989.

46. Snider P, Zeff J. 1987-1989. Personal letters and communications.

47. Zeff J. Convention theme: “what is a naturopathic physician?”. AANP Q News. 1988;3:1. 11

48. Snider P., Zeff J. Definition of naturopathic medicine: first draft. AANP Q News. 1988;3:6–8.

49. North American Association of Naturopathic Medical Colleges Integration Project Survey 1997-1999. Preliminary report. October 26, 1999. Snider P, Zeff J, co-chairs. Mitchell M, Bastyr University Integration Project Student Task Force Chair. Monwai M, database and research assistant.

50. Snider P., Zeff J. Integration project report on survey data and proposed principles of naturopathic medicine to the AANMC dean’s council, 1999.

51. The integration project update 2000: AANP house of delegates principles survey, presented by Mitchell M, IP student task force chair 1997-2000. Comments presented by Snider S, Zeff J, co-chairs integration project 1996-2000. Monwai M, database manager. Saunders F, data analyst.

52. O’Keefe M., Milliman B., Zeff J. Proposed new principles of naturopathic medicine: wellness, least force, relieve suffering. Submitted to the AANP house of delegates. 1996.

53. Resolution introduced in house of delegates regarding new principles: passed 2000 AANP convention, Seattle, WA. The house of delegates recommended that the discussion be moved to the academic community involved in clinical theory and practice for development.

54. Zeff J. The process of healing: a unifying theory of naturopathic medicine. J Naturopath Med. 1997;1:122–126.

55. Snider P., Zeff J., Sensenig J., et al. Towards a unifying theory of naturopathic medicine. Portland, OR: AANP plenary session; 1996.

56. Snider P. Integration project: timeline, scope of work, goals, methods. Proposal adopted by CNMC 1996, readopted by AANMC 1997–1998.

57. CNME report from Bastyr University, 1999. Standard XI and appendices: curriculum.

58. AANMC dean’s council minutes and correspondence, 2000.

59. Snider P, Downey C, co-chairs. Invitation letter, supporting information, agenda, minutes, tools and materials. AANMC integration project retreat for naturopathic philosophy and clinical theory faculty, basic sciences chairs and clinic directors. August 20-21, 2001.

60. Snider P, Payne S. Making naturopathic curriculum more naturopathic: agendas, minutes, 1999-2001. Clinic faculty task force on integration. Faculty development retreat, Bastyr University, August 17, 1998.

61. Kott A., Fruh D., et al http://www.fightchronicdisease.org/sites/default/files/docs/2009_PFCDAlmanac_0.pdf. Accessed 8/10/2011

62. Goldmann D.A., Weinstein R.A., Wenzel R.P., et al. Strategies to prevent and control the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms in hospitals—a challenge to hospital leadership. JAMA. 1996;275(3):234–240.

63. Eggleston K., Zhang R.F., Zeckhauser R.J. The global challenge of antimicrobial resistance: insights from economic analysis. Int J Env Res Pub Health. 2010;7(8):3141–3149.

64. Pizzorno J.E., Snider P., Katzinger J. Naturopathic medicine. In: Micozzi M.S., ed. Fundamentals of complementary and alternative medicine. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2006:159–192.

65. Cannon W. Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 1929;9(3):399–431.

66. Gern J.E. The ABCs of rhinoviruses, wheezing, and asthma. J Virol. 2010;84(15):7418–7426.

67. MacDowell A.L., Bacharier L.B. Infectious triggers of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25(1):45–66.

68. Gern J.E. Mechanisms of virus-induced asthma. J Pediatr. 2003;142(2 Suppl):S9–S13. discussion S13–4

69. Ghildyal R., Dagher H., Donninger H., et al. Rhinovirus infects primary human airway fibroblasts and induces a neutrophil chemokine and a permeability factor. J Med Virol. 2005;75:608–615.

70. Mallia P., Contoli M., Caramori G., et al. Exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): focus on virus induced exacerbations. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:73–97.

71. Papadopoulos N.G., Psarras S. Rhinoviruses in the pathogenesis of asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3:137–145.

72. Wark P.A., Johnston S.L., Bucchieri F., et al. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:937–947.

73. Contoli M., Message S.D., Laza-Stanca V., et al. Role of deficient type III interferon-lambda production in asthma exacerbations. Nat Med. 2006;12:1023–1026.

74. Lipworth B.J. Systemic adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroid therapy—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Int Med. 1999;159(9):941–955.

75. Zonana-Nacach A., Barr S.G., Magder L.S., et al. Damage in systemic lupus erythematosus and its association with corticosteroids. Arth Rheum. 2000;43(8):1801–1808.

76. Gourgiotis S., Kocher H.M., Solaini L., et al. Gallbladder cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196(2):252–264.

77. Duong T.H., Flowers L.C. Vulvo-vaginal cancers: risks, evaluation, prevention and early detection. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):783–802. x

78. Bhattacharyya N., Frankenthaler R., Gomolin H., et al. Clinical and pathologic characterization of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the head and neck. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107(9 Pt 1):801–806.

79. Ezzati M., Lopez A.D., Rodgers A., et alAnd the Comparative Risk Assessment Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347–1360.

80. McGinnis J.M., Foege W.H. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207–2212.

81. Ridker P.M., Cushman M., Stampfer M.J., et al. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(14):973–979.

82. Tuomilehto J., Lindstrom J., Eriksson J.G., et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–1350.

83. Saaristo T., Moilanen L., Korpi-Hyovalti E., et al. Lifestyle intervention for prevention of type 2 diabetes in primary health care one-year follow-up of the Finnish National Diabetes Prevention Program (FIN-D2D). Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2146–2151.

84. Hanson M.A., Gluckman P.D. Developmental origins of health and disease: new insights. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102(2):90–93.

85. Booth F.W., Laye M.J., Lees S.J., et al. Reduced physical activity and risk of chronic disease: the biology behind the consequences. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;102(4):381–390.

86. Seaward B.L. Stress and human spirituality 2000: at the cross roads of physics and metaphysics. J App Psycho Biofeedback. 2000;25(4):241–246.

87. Zarychanski R., Houston D.S. Anemia of chronic disease: a harmful disorder or an adaptive, beneficial response? CMAJ. 2008;179(4):333–337.

88. Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents (ESAs) 11.0807 US FDA. Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugSafetyPodcasts/ucm077204.htm, 2007. Accessed 8/10/2011

89. Moylan J.S., Reid M.B. Oxidative stress, chronic disease, and muscle wasting. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35(4):411–429.

90. Green C.R., Nicholson L.F. Interrupting the inflammatory cycle in chronic diseases–do gap junctions provide the answer? Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(12):1578–1583.

91. Subramanian V., Ferrante A.W. Obesity, inflammation, and macrophages. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2009;63:151–159. discussion 159-162, 259-268

92. Booth F.W., Lees S.J. Fundamental questions about genes, inactivity, and chronic diseases. Physiol Genomics. 2007;28(2):146–157.

93. Bojalil R. Are we finally taming inflammation? Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1215–1216.

94. Inflammation: a unifying theory of disease? Research is showing that chronic inflammation may be the common factor in many diseases. Harv Health Lett. 2006;31(6):4–5.

95. Goldstein D.S. Computer models of stress, allostasis, and acute and chronic diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1148:223–231.

96. Romero L.M., Dickens M.J., Cyr N.E. The reactive scope model—a new model integrating homeostasis, allostasis, and stress. Horm Behav. 2009;55(3):375–389.

97. McEwen B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(3):171–179.

98. McEwen B.S., Wingfield J.C. What is in a name? Integrating homeostasis, allostasis and stress. Horm Behav. 2010;57(2):105–111.

99. Schnaper H.W., Hubchak S.C., Runyan C.E., et al. A conceptual framework for the molecular pathogenesis of progressive kidney disease. Ped Nephr. 2010;25(11):2223–2230.

100. Woolf K., Reese C.E., Mason M.P., et al. Physical activity is associated with risk factors for chronic disease across adult women’s life cycle. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(6):948–959.

101. Martinez-Lavin M., Vargas A. Complex adaptive systems allostasis in fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(2):285–298.

102. Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults—the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258.

103. Bough K.J., Rho J.M. Anticonvulsant mechanisms of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2007;48(1):43–58.

104. Festa A., et al. The relation of body fat mass and distribution to markers of chronic inflammation. Int J Obesity. 2001;25(10):1407–1415.

105. Faber D.R., van der Graaf Y., Westerink J., Visseren F.L.J. Increased visceral adipose tissue mass is associated with increased C-reactive protein in patients with manifest vascular diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(1):274–280.

106. Ghanem F.A., Movahed A. Inflammation in high blood pressure: a clinician perspective. J Am Soc Hypertension. 2007;1(2):113–119.

107. Libby P., Ridker P.M., Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1135–1143.

108. Ridker P.M., Buring J.E., Shih J., et al. Prospective study of C-reactive protein and the risk of future cardiovascular events among apparently healthy women. Circulation. 1998;98(8):731–733.

109. Rozanski A., Blumenthal J.A., Kaplan J. Act of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99(16):2192–2217.

110. Krabbe K.S., Pedersen M., Bruunsgaard H. Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Experimen Gerontol. 2004;39(5):687–699.

111. Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physio Rev. 2002;82(1):47–95.