Chapter 1 A decision-making framework for complementary and alternative medicine

Introduction

‘Complementary and alternative medicine’ (CAM) is an overarching term that encapsulates a diverse range of modalities considered to be outside the scope of orthodox medicine. According to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the US1 and the National Institute of Complementary Medicine in Australia,2 both of which are leading authorities in CAM research, these therapies can be divided into five distinct categories, including whole medical systems (such as naturopathy, homeopathy, Western herbalism, Ayurveda, indigenous and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)); energy medicine (including therapeutic touch, flower essences and Reiki); biologically based interventions (such as nutrients, plant and animal products); manipulative therapies (including massage, chiropractic, osteopathy and reflexology), and mind–body interventions (such as tai chi, yoga, meditation and progressive relaxation).

Given the recent trend towards integrative medicine, the line separating CAM from orthodox medicine is becoming less distinct. This is further perpetuated by vague definitions of CAM. NCCAM,1 for example, defines CAM as ‘a group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine’. Defining CAM by what it is not is no longer appropriate given the changing face of healthcare and the integration of CAM into medical, nursing and allied health curricula. CAM is more fittingly defined as a diverse group of health-related modalities that promote the body’s innate healing ability in order to facilitate optimum health and wellbeing, while retaining a core focus on holism, individuality, education and disease prevention.

Consumer interest in these therapies has escalated over the past few decades. In fact, more than fifty per cent of the Western population,3 including the Australian,4,5 US6 and Japanese populations,7 have used CAM at least once over a 12-month period. Biologically based interventions, such as nutrient supplements and herbal medicines, and manipulative therapies, such as massage and chiropractic, are among those demonstrating the highest level of use. Over the same period, close to ten per cent of UK adults,8 twelve per cent of US adults,6 and twenty-three9 to forty-four per cent of Australians5 have consulted a CAM practitioner; chiropractic and osteopathy were the most commonly used services.The growing interest in CAM across the globe can be attributed to a number of factors. Although earlier studies signalled consumer dissatisfaction with orthodox medicine as a leading cause of CAM use,3 more recent reports indicate that an aspiration for active healthcare participation, greater disease chronicity and severity, holistic healthcare beliefs, and an increase in health-awareness behaviour are more likely to predict CAM use.10–12 These transformations in consumer attitude and health behaviour have parallelled changes in the way many CAM specialties practise.

The shift towards evidence-based practice, along with issues concerning education and regulation, are now shaping the future of many system-based modalities, particularly naturopathy, Western herbalism and TCM. These changes suggest that the aforementioned specialties may be in the process of professionalisation, that is, transforming from occupation to profession. Unification of the CAM profession, controlled entry into the vocation (i.e. occupational closure), closer alignment to the mainstream scientific-evidence-based practice paradigm, and the development and standardisation (or codification) of knowledge are all essential criteria for the professionalisation of CAM occupations.13,14 Although codification involves claiming a unique body of knowledge, it also requires an understanding of how that knowledge can be applied to practice.15 Clinical decision-making models play a pivotal part in this translational process. This chapter will therefore introduce the reader to a decision-making framework for complementary and alternative medicine (DeFCAM), and demonstrate how this framework may facilitate the application of CAM knowledge into clinical practice. The uptake of such a model may also help to espouse the ongoing development of CAM and enhance the professionalism of CAM practitioners.

CAM philosophy

The practice of CAM is guided by the art, science and principles of each profession. Even though the art and science of the CAM therapies are distinctly different from each other, many of these professions share similar philosophies. Some of the core principles underlying these philosophies that are shared by therapies such as naturopathy, Ayurveda, TCM, chiropractic, osteopathy, Western herbalism and homeopathy,16–24 are as follows:

Clinical decision-making models

Over the past few decades, a number of decision-making models have emerged within the healthcare sector. The general aim of these frameworks was to guide practitioners through the process of decision making in often complex clinical environments. Examples of some of the more common models used in clinical practice are highlighted in Table 1.1. Many of these frameworks were originally designed to improve documentation in the healthcare sector rather than guide clinical decision making. SOAP, DAP, OHEAP and SNOCAMP, for example, while providing a simple, systematic and consistent approach to documentation in the clinical environment, provide very little direction for practitioners in the management of client problems. Fortunately, several models have since emerged that attempt to address this problem.

Table 1.1 Clinical decision-making models used in the healthcare sector

| DAP | Data, assessment, plan |

| FARM | Findings, assessment, recommendations/resolutions, management |

| HOAP | History, observations, assessment, plan |

| Nagelkerk (2001) model | Problem, assessment, diagnoses, diagnostics, single diagnosis, treatment plan |

| Nursing process | Assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation |

| Nutrition care process | Assessment, diagnosis, implementation, monitoring and evaluation |

| Participative decision-making model (Ballard-Reisch 1990) | Information gathering, information interpretation, exploration of treatment alternatives, criteria establishment for treatment, weighing of alternatives against criteria, alternative treatment selection, decision implementation, evaluation of implemented treatment |

| Prion (2008) model | Situation prime, gather cues, determine relevant/non-relevant cues, cue grouping, problem identification, patient status, cause hypothesis, intervention, gather more information |

| OHEAP | Orientation, history, exam, assessment, plan |

| SNOCAMP | Subjective data, nature of presenting complaint, objective data, counselling, assessment, medical decision making, plan of treatment |

| SOAP | Subjective data, objective data, assessment, plan |

One of the earliest participative decision-making frameworks to surface in orthodox medicine was that developed by Ballard-Reisch (1990).25 Originally designed for physicians, the eight-stage participative decision-making model aimed to provide a more client-centred and structured approach to client care. Although the need for a participative approach was timely and well justified, the stages of the model lacked sufficient description. There is also little evidence to indicate that, to date, this process has been accepted or taken up by the wider medical community. This is not to say that other participative models have not been adopted by physicians, only that the use of such frameworks has not been well published.

A well-documented decision-making framework is the nursing process. This model has been widely accepted by the nursing community and is recognised internationally and integrated into most nursing curricula.26 In essence, the process provides a client-centred framework for nursing practice ‘by which nurses use their beliefs, knowledge, and skills to diagnose and treat the client’s response to actual and potential health problems’.26

The benefits that the nursing process delivers to the nursing profession have been recognised by other disciplines, including the dietetics community, which has led to the subsequent development of the nutrition care process.27,28 It is not surprising, therefore, that there is considerable overlap between the two processes. In fact, there are many similarities between most decision-making models, including the Prion29 clinical reasoning model, Nagelkerk30 diagnostic reasoning process and the aforementioned frameworks. The key themes that arise from all of these models are assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation and evaluation.

Another concept that is implied in the Ballard-Reisch model25 but not explicitly stated in any other decision-making process, yet a component that is critical to all client–practitioner interactions, is rapport. Incorporating rapport into a clinical decision-making framework, together with the five themes listed above, would in effect create a more complete, systematic and structured approach to the management of client problems. DeFCAM is therefore one of only a few, if not the only known model to adequately capture all of these themes within one process. Although the development of such a model could be perceived by some as merely following the trends of other professions, there is in fact real merit for the CAM profession in adopting such a framework, which the following section alludes to.

The decision-making framework for complementary and alternative medicine (DeFCAM)

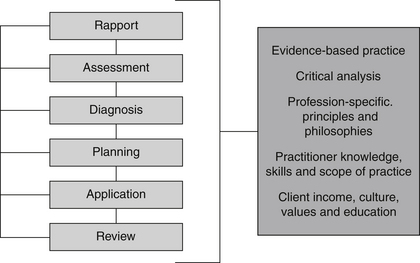

DeFCAM is a systematic clinical reasoning framework developed by the author specifically for CAM and integrative healthcare practitioners. The six stages of the process include rapport, assessment, diagnosis, planning, application and review (Figure 1.1). The process is primarily aimed at guiding CAM practitioner thinking, assessment and care, and, as such, is likely to generate benefits for the CAM practitioner, the client and members of the integrative healthcare team, including:

While DeFCAM is displayed in a linear fashion, and maybe applied as such, the process is not unidirectional. In fact, each stage of the process is interlinked because just as in clinical practice, the acquisition of new information requires a CAM practitioner to shift between various stages of assessment, diagnosis and planning until an appropriate treatment plan is developed. Still, the six stages of DeFCAM are presented in a logical order because each phase of the process acts as a prerequisite for subsequent stages.

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, there are a number of concepts that overarch DeFCAM. This is because each of these constructs exercises significant influence on a CAM practitioner’s decision making. In particular, each factor directs how a clinician should assess a client, how the data should be interpreted and what interventions should be selected. By taking these elements into consideration, a CAM practitioner can make attempts to resolve any limitations in their decision-making style in order to deliver more effective clinical care.

Rapport

Establishing client rapport is the first and most important phase of DeFCAM. By developing rapport with the client, communication between the practitioner and client may improve, as may assessment, treatment compliance and the achievement of expected treatment outcomes.33,34 Even though a therapeutic relationship may develop throughout the consultation, it is important that time is allocated at the beginning of the visit to build client trust. In order to develop trust and decrease client anxiety, the practitioner should introduce themselves to the client and allow the individual to verbalise what they expect from the consultation.33 The CAM practitioner may also build trust and strengthen client rapport by being open, empowering, empathetic, objective, honest, non-judgemental, flexible, consistent, committed and interested in the health and welfare of the client.33–35 These attributes should not only be expressed verbally, but also non-verbally through facial expressions, eye contact and posture.33–35 Effective communication and optimal client–practitioner interaction may be further facilitated by identifying and respecting differences in client age, gender, developmental stages, cognitive ability, values, beliefs and culture.35

Assessment

The assessment phase of DeFCAM involves the acquisition, validation and organisation of client information, and the identification of factors that may influence client health and wellbeing. Given that assessment informs every succeeding stage of DeFCAM, the accuracy and inclusivity of the process will almost certainly impact on client outcomes. By following a transparent and systematic assessment process, clinicians may be able to enhance the quality of clinical assessment by reducing the potential for data omission. One way CAM practitioners may approach clinical assessment is through the use of theoretical models, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs36 or the Neuman systems model.37 Even though these models are useful for recognising pertinent physiological, social or psychological needs of a client, they do little to guide the practitioner through the clinical assessment process overall. This is also the case for traditional clinical methods, including the head-to-toe and body systems approaches. The CAM assessment process addresses these limitations by providing a more complete, holistic and systematic approach to clinical assessment, incorporating not only the health history and physical examination, but also pertinent diagnostics, thereby enabling CAM practitioners to effectively identify the underlying cause of the presenting condition. The collection of detailed information also gives rise to a more informed CAM practitioner, who is capable of making prompt and appropriate decisions about the need for referral. This process is described in greater detail in chapter 3.

Diagnosis

In the third phase of DeFCAM, data acquired from the client assessment are clustered into logical groups, which enables hypotheses or diagnoses to be generated. This process, known as diagnostic reasoning,35 is critical to the generation of clinical diagnoses. Even though CAM practitioners and other non-medical health professionals are not legally permitted to formulate ‘medical’ diagnoses, at least not in Australia,38 some professions, including nursing and dietetics, have overcome this practice limitation by developing a list of diagnoses that they can legally identify and treat. CAM practitioners could follow a similar path to that of these professions and establish their own set of CAM diagnoses in order to avoid litigation around claims of practising medicine.

As with nursing and nutrition diagnoses, a CAM diagnosis also consists of a client-centred problem (actual or potential) and the aetiology of the problem.33,39 Such an approach benefits practitioners because the problem component indicates what the client outcome should be at the review stage, whereas the aetiology component directs the clinician towards the cause of the condition, and thus points the practitioner towards an appropriate approach to treatment.26 As a result, CAM diagnoses may provide a framework for the delivery of CAM treatment,39 and thereby link CAM philosophy to clinical practice (i.e. identifying and treating the cause of the complaint), and improve client prognosis and management.

Planning

The planning phase of DeFCAM focuses on the development of goals in order to identify and prioritise strategies that may prevent, reduce or resolve client problems, or that facilitate or augment client function. But before these goals can be developed, client problems must first be prioritised. One model that is often used to prioritise client problems is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.26 However, Maslow’s model does not inform practitioners how to prioritise within each of the six needs; for instance, what physiological problems should a practitioner treat first? Determining what CAM diagnosis to initially address should be ascertained by the level of risk that the problem poses to the client, with conditions demonstrating a higher risk of harm demanding a higher priority of care.35,39

Once CAM diagnoses have been prioritised, the most important diagnosis can then be used to formulate the goals of treatment. These goals should be client-centred, individualised, observable, measurable, mutually derived and realistic, with each goal addressing only one problem and one outcome.35,39 Treatment goals must also take into consideration the cost of treatment, available resources, client age, environment, values, beliefs and culture, as well as social status, client self-efficacy, motivation and readiness to change, and the client’s cognitive, physical and emotional capacity.40,41

Application

After CAM diagnoses have been formulated and treatment goals and expected outcomes established, appropriate interventions may then be commenced. As with the planning phase, the treatment options need to be negotiated between the CAM practitioner and the client in order to enhance independence, control, dignity and self-esteem.40 Client involvement in clinical decisions may also improve treatment compliance and thus facilitate progression towards expected outcomes. The treatments should also be aimed at achieving the goals identified in the planning stage.

Due to the eclectic nature of CAM practice, the diversity of CAM education around the globe and personal preference, very few CAM practitioners are likely to employ the same approach, so it would be inappropriate to dictate which therapies CAM practitioners should prescribe for specific conditions, though it is recommended that the choice of interventions be based on the best available evidence so as to maximise improvements in client outcomes and the quality of care, and to minimise harm and suffering.42 This concept of evidence-based practice and how it applies to CAM practice is discussed in greater detail in chapter 6. Therapies that are supported by clinical evidence, which may be integrated into CAM practice, are outlined in chapter 9.

Review

The review stage of the decision-making framework utilises assessment techniques to determine whether the treatment approach was effective, if the expected outcomes of client care were achieved,35 if illness was prevented and whether homeostasis was restored. Clinicians need to appreciate that clients may find it difficult to achieve the expected outcomes of treatment if a practitioner’s knowledge base and level of skill are inadequate, and if the client lacks understanding, self-efficacy or is not involved in the treatment process.35,43 The achievement of treatment goals may be facilitated by involving clients in DeFCAM, and by CAM practitioners engaging in reflective practice. This rational and conscious process of systematically and rigorously reflecting on one’s practice enables clinician’s to challenge existing approaches and to learn from one’s actions.44

Summary

At present, there is a paucity of universally recognised, clearly constructed, systematic decision-making frameworks to guide the practice of system-based CAM. In order for many systems of CAM to develop professionally, a body of knowledge must be developed and codified. The development of DeFCAM endeavours to facilitate the professionalisation of these CAM systems and to improve clinical reasoning in CAM practice by providing a structured process for clinical care. DeFCAM consists of six interrelated stages, including rapport, assessment, diagnosis, planning, application and review. These stages are best remembered by the acronym RADPAR. It is envisaged that this framework will provide the necessary foundations for the development of a codified knowledge base for CAM disciplines in order to improve professional status, quality of care and client outcomes. The close alignment of DeFCAM with CAM philosophy also ensures that the core principles of CAM practice have not been discounted. The assessment phase of DeFCAM, for example, addresses the principle of holism and the need to identify the cause of the presenting condition; CAM diagnosis focuses on treating the primary cause of the complaint, as well as preventing illness; the planning approach maintains client-centredness and individualism; application applies the concept of evidence-based practice to minimise harm, optimise health and wellbeing, and alleviate suffering; and review assesses whether the prevention of illness and the restoration of homeostasis has been attained. A more detailed discussion of each of these stages is presented in the chapters that follow, beginning with rapport.

1. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). (2000) What is CAM? NCCAM, Maryland. Accessed at <http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/overview.htm >, 1 March 2009.

2. National Institute of Complementary Medicine (NICM). About complementary medicine. Sydney: NICM; 2009. Accessed at <www.nicm.edu.au/content/view/14/17/ >, 1 March 2009

3. Leach M.J. Public, nurse and medical practitioner attitude and practice of natural medicine. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery. 2004;10(1):13-21.

4. MacLennan A.H., Myers S.P., Taylor A.W. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: costs and beliefs in 2004. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;184(1):27-31.

5. Xue C.C.L., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national population-based survey. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2007;13(6):643-650.

6. Barnes P.M., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Seminars in Integrative Medicine. 2004;2(2):54-71.

7. Hori S., et al. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use amongst outpatients in Tokyo, Japan. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008;8:14-23.

8. Thomas K., Coleman P. Use of complementary or alternative medicine in a general population in Great Britain. Results from the National Omnibus survey. Journal of Public Health. 2004;26(2):152-157.

9. Lin V., et al. The Practice and Regulatory Requirements of Naturopathy and Western Herbal Medicine. Melbourne: Government of Victoria, Department of Human Services; 2006.

10. Busato A., et al. Health status and healthcare utilisation of patients in complementary and conventional primary care in Switzerland: an observational study. Family Practice. 2006;23(1):116-124.

11. Robinson A., Chesters J., Cooper S. People’s choice: complementary and alternative medicine modalities. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2007;12(2):99-119.

12. Sirois F.M., Purc-Stephenson R.J. Consumer decision factors for initial and long-term use of complementary and alternative medicine. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2008;13(1):3-20.

13. Cant S., Sharma U. Professionalization of complementary medicine in the United Kingdom. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 1996;4:157-162.

14. Hirschkorn K.A. Exclusive versus everyday forms of professional knowledge: legitimacy claims in conventional and alternative medicine. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(5):533-557.

15. Sharma U. Professions, power and the patient: some more useful concepts. In: Sharma U., editor. Complementary medicine today: practitioners and patients. London: Routledge, 1995.

16. Cassidy C.M. Social and cultural context of complementary and alternative medical systems. In: Micozzi M.S., editor. Fundamentals of complementary and alternative medicine. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

17. Ebrall P.S. Chiropractic. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

18. Howden I. Homeopathy. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

19. Lucas N., Moran R. Osteopathy. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

20. Matthews S. Ayurveda. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

21. Myers S., et al. Naturopathic medicine. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

22. Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T. Textbook of natural medicine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.

23. Patching van der Sluijs C.G., Bensoussan A. Traditional Chinese medicine. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

24. Wohlmuth H. Herbal medicine. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

25. Ballard-Reisch D.S. A model of participative decision making for physician–patient interaction. Health Communication. 1990;2(2):91-104.

26. Iyer P.W., Taptich B.J., Bernocchi-Losey D. Nursing process and nursing diagnosis, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995.

27. Bueche J., et al. Nutrition care process and model Part I: the 2008 update. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108(7):1113-1117.

28. Lacey K., Pritchett E. Nutrition care process and model: ADA adopts road map to quality care and outcomes management. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(8):1061-1072.

29. Prion S. The case study as an instructional method to teach clinical reasoning. In Higgs J., editor: Clinical reasoning in the health professions, 3rd ed., Amsterdam: Elsevier/Butterworth Heinemann, 2008.

30. Nagelkerk J. Clinical decision-making in primary care. In: Nagelkerk J., editor. Diagnostic reasoning: case analysis in primary care practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

31. Higgs J. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. In Higgs J., editor: Clinical reasoning in the health professions, 3rd ed., Amsterdam: Elsevier/ Butterworth Heinemann, 2008.

32. Dowding D., Thompson C. Decision analysis. In: Thompson C., Dowding D., editors. Clinical decision making and judgement in nursing. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:131-145.

33. DeLaune S.C., Ladner P.K. Fundamentals of nursing: standards and practice, 3rd ed. Albany: Thomson Delmar Learning; 2006.

34. Leach M.J. Rapport: a key to treatment success. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2005;11(4):262-265.

35. Harkreader H., Hogan M.A., Thobaben M. Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical judgement, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2007.

36. Taylor C., et al. Fundamentals of nursing: the art and science of nursing care, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

37. Ume-Nwagbo P.N., DeWan S.A., Lowry L.W. Using the Neuman systems model for best practices. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2006;19(1):31-35.

38. Weir M. Complementary medicine: ethics and law, 3rd ed. Ashgrove: Prometheus Publications; 2007.

39. Crisp J., Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s fundamentals of nursing, 3rd ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2008.

40. Kozier B., et al. Fundamentals of nursing: concepts, process, and practice, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education; 2004.

41. Treasure J., Maissi E., et al. Motivational interviewing. In Ayers S., editor: Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine, 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

42. Leach M.J. Evidence-based practice: a framework for clinical practice and research design. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2006;12:248-251.

43. Leach M.J. Revisiting the evaluation of clinical practice. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2007;13(2):70-74.

44. Rolfe G., Freshwater G., Jasper D. Critical reflection for nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2001.