CHAPTER 4 A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery Patient

Beyond Formal Measurements. Decision Making and Tips to Enhance Patient Satisfaction and Outcomes

The accurate evaluation of the patient who presents for consideration of aesthetic improvement of the periorbita is as important as any of the other components that lead to a successful outcome. Often an unfavorable result can be traced back to a less than precise evaluation of the situation at hand that would include failure to observe some of the salient findings that were neither protected or improved. Frequently patients present with a general dissatisfaction of the aging appearance of the periorbita, but are not quite exactly sure what are the particulars that bother them, the options for improvement, or the potential risks with the multitude of approaches. As in all aspects of medicine, an accurate history, physical examination, and thorough discussion with the patient will lend itself to better treatment planning. This combined with precise surgical execution, will nearly always result in a happier patient. More often, even subtle findings or clues that lend themselves to particular maneuvers that will optimize the overall result can be seen before (or are seen retrospectively) by careful evaluation of the patient and review of preoperative photographs. In this chapter, I will discuss some of the important aspects of this process, including choices and decision making that must be considered in every patient evaluation for the individual who presents for periorbital cosmetic surgery.

History

The patient’s purpose for their consultation and general history is commonly first obtained by a nurse, medical assistant, or resident/fellow in training. At times this is obtained only and directly by the surgeon him/herself. If the initial history is taken by someone other than the operating surgeon, it behooves the surgeon to review the obtained data and often supplement the historical information with data that will improve and clarify the overall patient status. This starts, as with all medical evaluations, with a chief complaint. Sometimes the chief complaint is disregarded only to be discovered after surgery when the patient states that although there is obvious improvement of the overall presenting condition, the main purpose for this patient proceeding with surgery was to improve a situation that was clearly stated in the chief complaint and possibly forgotten, ignored or not adequately addressed in the final analysis. Obviously, once the patient makes this statement, their expectations are that this will be addressed, despite the elaboration and performance of other procedures that might globally improve the appearance of the periorbita and face. These additional procedures are usually recommended after either an expanded description of the chief complaint, or by questions asked directly by the medical assistant or physician which further clarify the situation and are then a prelude to a more meaningful discussion of this and the potential options for their remedy.

History of allergies to medications as well as other known substances (including latex, injectable anesthetics, etc.) should be discussed. For instance, patients will often state that they are ‘allergic to lidocaine’ and when on further elaboration they claim that asymptomatic palpitations were noted during a dental procedure, for example. Often they will consider this an allergy or contraindication to use, when in fact under controlled and monitored anesthesia this may not be the case. If they claim an allergy to a particular drug, they should also describe (if they can recall) exactly what type of ‘reaction’ occurred during the usage of this medication or drug. Commonly patients will state other (non-allergic) symptoms including ‘upset stomach,’ nausea, lethargy or sleeplessness, all of which are obviously not necessarily true allergic responses. Patients should be directly questioned on the use of any anti-inflammatory medication or any drugs which could potentially increase bleeding time; this medication will probably be discontinued for at least one to two weeks prior to surgery. A list of medications that could alter bleeding times may be given to them for a review and reminder. They should also be questioned regarding personal experiences with bruising or bleeding which may help counsel patients on what they can expect regarding their appearance immediately after surgery.

Finally, a history of dry eye symptoms, use of artificial tears and other topical emollients for the eye surface, as well as the use of contact lenses should be elicited that may give you more information than can be obtained by didactic measurements.1,2 For instance, if a patient states that they have intermittent dry eye symptoms of irritation, pain, light sensitivity, and decreased vision, an elaboration of these questions may reveal that the patient infrequently uses tear supplements and by increasing their usage of the topical agents dramatically reduces and even eliminates symptoms. These patients must be approached (i.e. for surgical candidacy) with great caution and the procedures may be modified to reduce the chance of increased ocular exposure symptoms. Similarly, if the patient states that their dry eyes are ‘terrible’ but also denies the use of tear supplements, or that they are able to tolerate contact lenses for days and weeks at a time without symptoms of dryness or irritation, they can do very well after surgery with regard to the concerns of potentially worsening dry eye symptoms. To the contrary, if a patient denies a history of dry eye symptoms but after further questioning reveals a complete intolerance to the use of contact lenses (due to pain and discomfort), can’t tolerate a fan or air-conditioning (i.e. in a car or plane) blowing near them due to enhanced ocular foreign body sensation, they may pose significant risk when proceeding with any eyelid surgery. Finally, women that are nearing menopause, immediately pre-, or postmenopause, should be warned that their incidence of dry eye symptoms can be worsened even when surgery is performed very well. As this is a common age for women to have cosmetic blepharoplasty, their increased symptomatology is often blamed on the surgery. Appropriate preoperative counseling lets them know that their worsening of symptoms may be expected and fortunately, is temporary in most situations. Finally, those individuals who have had keratorefractive surgery (i.e. LASIK and related procedures), clearly exhibit a greater risk and incidence of dry eye symptomatology after surgery, and this should be discussed beforehand, so that the choice to proceed with cosmetic blepharoplasty, understanding the risks, becomes theirs.

The physical examination

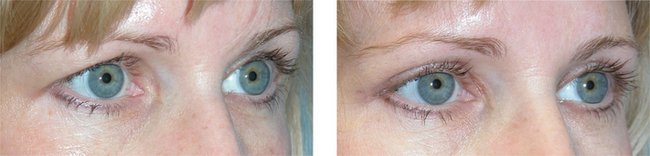

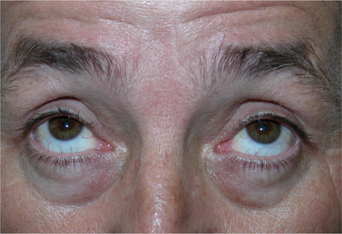

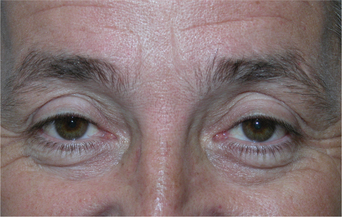

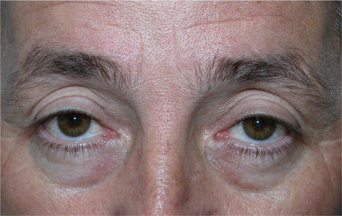

The first part of the physical examination begins during the history taking process. I commonly will simply observe a patient while they are speaking, and simultaneously evaluate them for animation and effects that may relate to either their complaints or possibly recommendations and treatment options. Asymmetries are commonly noted, especially with regard to the position of the eyebrow(s), as well as the size of the horizontal and vertical palpebral apertures (Fig. 4-1). At times during this discussion, even subtle facial weakness or dyskinesis can be identified which must be considered while entertaining surgical options, as well as documentation of its presence as it may only become obvious to the patient after surgery. A prelude to the patient’s personality can also at times be detected by their habits and mannerisms. Those who are shy or even untruthful will not as frequently maintain eye contact. Those who continuously question or even argue every statement or recommendation negatively, may cause trouble after surgery even if it is performed at or near perfection. Those patients who have been unhappy with all prior experiences and speak unfavorably about many or all prior treating physicians are also likely to be dissatisfied with your efforts. So the history portion of the consultation is not simply performed to obtain routine historical data, but the treating surgeon should be keenly observant of facial expression as well as personality and mannerism traits of the individual which will lead to the best possible treatment recommendations, that might include no treatment at all.

General upper facial assessment

Once the general assessment and more casual observation (during the history-taking portion) of the patient’s situation has been obtained, a more detailed evaluation should follow, including more formal measurements and notations (see Chapter 3) of the eyebrow position and asymmetry. There should be careful evaluation of forehead and periorbital lines and furrows, which will often indicate chronic and habitual animation (Figs 4-2 to 4-5). I do not believe that formal or precise brow measurements will dictate whether or not to perform brow surgery (Fig. 4-6); however it will serve as a basis for discussion of the possible options. For instance, I will often request to review old photographs of the patient to determine their opinion on their brow position in the past and present, and then will discuss the reality of actual brow descent. Photographs are generally helpful for many aspects of periorbital surgery (see Chapter 2), especially in lieu of asymmetry and general aesthetic appearance and ultimately the goal for our rejuvenative efforts (Fig. 4-7). Nonetheless, useful didactic measurements including the vertical and horizontal palpebral fissures, margin to reflex distance (MRD1) and lower lid position with regard to shape, retraction, canthal position and lower eyelid laxity should be determined (see Chapter 3). I have not found reliance on snap-back or lower eyelid distraction maneuvers particularly useful as a screening tool for the necessity (or not) for canthpexy/plasty, especially in lieu of my philosophy that most lower lid surgical procedures (except in the very young) require routine, varying degrees of canthal support5 (see Chapter 15). These maneuvers, however, may simply confirm the necessity for lower eyelid/canthal re-enforcement procedures, and vectors for commissure support or repositioning (Fig. 4-8). They may also serve as an illustration (to the patient) of the need for particular ancillary procedures at the surgical setting.

Although I have not found absolute brow position to be a qualifier for the suggestion of browplasty, this observation as well as the amount of brow laxity can often be helpful in determining whether further brow descent will be likely after upper blepharoplasty alone.3,4 The brow shape and contour should also be considered (see Chapter 6). An assessment of relative globe prominence should be made, especially in lieu of lid position anomalies or asymmetries. Globe prominence is not always related to orbital pathology (such as thyroid exophthalmos or other orbital processes including lesions/tumors and old fractures) and may be due to a host of situations including (but not limited to), maxillary hypoplasia (Fig. 4-9), axial myopia (Fig. 4-10), or prior surgery (Fig. 4-11). Formal measurements including Hertel exophthalmometry are usually not required, but may be used for confirmation of the general assessment. The globe prominence will significantly impact both the selected surgical procedures and the modification of ancillary steps (including canthopexy/plasty) to avoid common pitfalls and achieve optimal results.

Examination of the upper eyelid

Typically several notations of the upper eyelid are important in giving a clear picture of the situation regarding the upper periorbita. Often patients complain of ‘hooding’ at the lateral aspect of the upper eyelid when this can be related to ptosis of the lateral eyebrow, simple volumetric diminishment, skin elastosis, and the appearance or illusion (see Chapter 2) of brow descent and excessive skin, or (more commonly) a combination of these factors. I then determine/approximate the relative amount of apparent skin ‘excess’, especially when evaluating prior to surgery which may also define placement of the upper eyelid crease. The upper eyelid should be evaluated for lid position (as it relates to the pupil) by measuring the margin reflex distance (MRD) to detect even mild upper lid ptosis or eyelid retraction, position and irregularities of the eyelid crease, and herniation of central and medial orbital fat (Fig. 4-12).

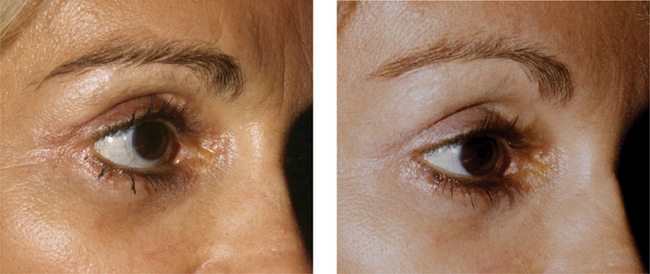

Lateral upper eyelid soft tissue ‘herniation’ may indicate a ptosis, malposition, and (even more rarely) pathology of the lacrimal gland. The native eyelid crease can be determined by raising the eyebrow digitally and observing the patient’s natural crease in down gaze. I usually pay less attention, however, to the native eyelid crease, since I more often try to surgically redefine the upper eyelid crease and fold according to where I (and the patient) believe aesthetically the crease should be placed or repositioned in any particular individual for the optimal rejuvenative result (Figs 4-13 and 4-14). I have found that the eyelid margin to fold measurement (MFD) and the patient’s predicted brow animation (do they continuously animate/raise brows during the interview etc.) also to be a more important determination of where to place the upper eyelid incision to reduce visibility of the incision (Fig. 4-15) and how much skin excision will be performed in any particular region of the upper eyelid. The MFD is the distance between the eyelid–lash/margin to the first skin fold (see Chapter 3). This is almost always a smaller measurement laterally consistent with lateral brow ptosis and volumetric changes, and a greater measurement medially, often just beneath the supraorbital notch (Fig. 4-15). I find the MFD helpful to assist in deciding on the best placement for the eyelid crease, as well as determination of how much skin will be removed in any particular area along the upper eyelid to produce the desired aesthetic effect in re-creating the upper eyelid fold (Fig. 4-16).

While evaluating for blepharoptosis, one should consider the margin reflex distance (Fig. 4-17) as well as the palpebral fissure measurement in downgaze (see Chapter 3). Even mild degrees of acquired blepharoptosis will show diminishment of the palpebral fissure in downgaze on the affected side whereas congenital ptosis shows a wider (vertical) palpebral fissure in downgaze is seen in the more ptotic upper eyelid. An assessment of the levator function should also be made which may in part determine the longevity of ptosis, including congenital ptosis situations which were previously unnoticed. Determination of eyelash fullness and position (especially lash ptosis) should be made as patients will often observe this after surgery when it had not been previously noted, even though present prior to the surgical procedure. Laxity of the pretarsal skin that manifests as horizontal striae should also be noted, as again once the eyelid fold is elevated this may become more apparent after surgery. Notations of prior surgery (even if not offered in the history) should be made. This is important not only in determining prior surgical procedures but in assessing where the new eyelid incision would be placed, whether preferred or mandated in an attempt to remove the old scar and avoid the possibility of leaving two!

Most important, the patient’s desires and expectations should be reviewed and compared with your findings. Ultimately, the outcome and satisfaction depends on delivering what the patient expects. Sensitivity to their wishes and achieving results that are rejuvenative without alteration and distortion (particularly in ethnic morphology, i.e. Asian eyelid etc.) will more often lead to a successful result.

Examination of the lower eyelid

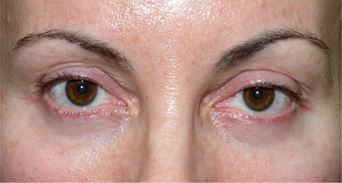

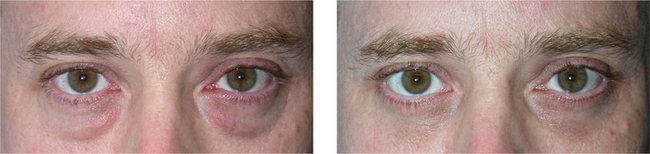

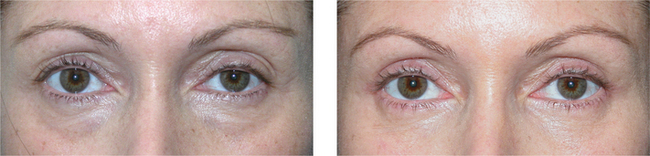

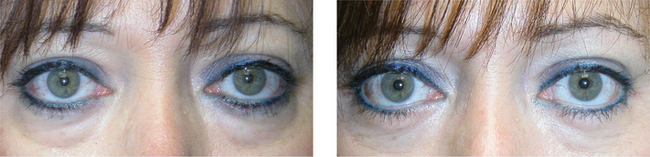

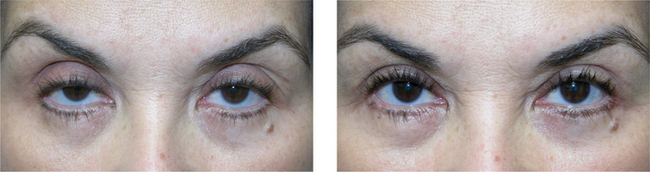

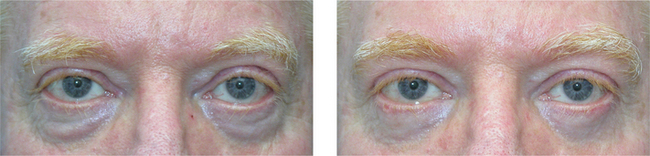

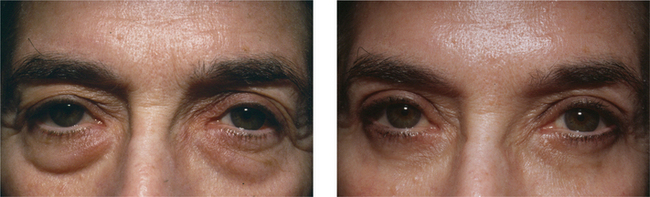

More commonly, patients who present for lower blepharoplasty will complain of either puffiness or ‘bags’ of the lower eyelids, ‘excess skin,’ and lower eyelid and lateral canthal lines. During this time, I will warn them of the unlikelihood of significant improvement of dynamic lines that are usually at best minimally or moderately affected by surgery. I usually start with assessing the appearance of herniated lower periorbital fat and grade this in a somewhat arbitrary fashion to assess where the greater and lesser amounts of ‘bags’ are present (Fig. 4-18). I do this on several occasions including immediately preoperatively as a ‘check and balance’ to be sure that the amount of surgery performed (intraoperative assessment) is consistent with the noted ‘herniation’ of the lower eyelids. This is most easily performed and exaggerated for better illustration by having the patient look in upgaze (Fig. 4-19), to the superior temporal field of the contralateral eye which will then more readily illustrate a sometimes elusive lateral fat pad. Having the patient smile (animation) may also completely conceal the lower eyelid fat, and relaxation is often necessary to elicit a more true determination quantitatively in any lower periorbital area, as well as cautioning the abundant removal of fat that might exaggerate lower eyelid ‘hollows’ after surgery (Fig. 4-20).

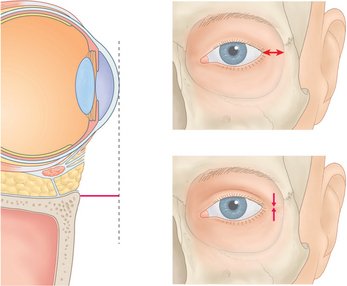

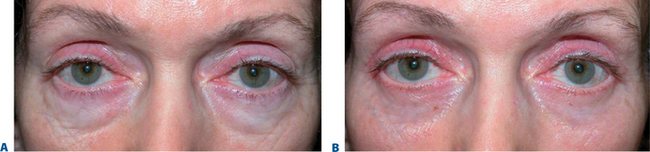

Figure 4-18 In primary position, the lower eyelid position and fat pad herniation should be acknowledged and documented.

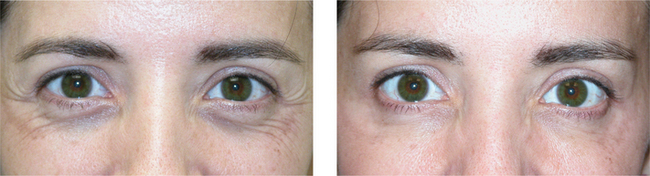

Animation is also important in determining the amount of rhytid formation that relates to this. At times it is a major component, however, whereas the static rhytids are less apparent which may be the only component that can be adequately improved upon by several surgical options. The amount of lower eyelid retraction, lower eyelid position, and canthal position (both vertical and displacement distance from the lateral orbital rim) should be determined (Fig. 4-21). As previously mentioned, although I find a ‘snap-back’ test and ‘distraction’ test in the lower eyelid less necessary for determining the need for canthal support (as it is routinely performed), some degree of lower eyelid laxity determination must be made which will indicate the amount and direction of canthal reinforcement. It will also indicate the tolerability of the lower eyelid to soft tissue distraction and excision, and how much will be required or permitted. As a general rule, the relatively enophthalmic eye may exhibit a significant degree of lower eyelid laxity, but supra-placement of the canthal suspension might cause a longer than tolerated (or permanent) over-correction (Fig. 4-22), while the exopthalmic eye that exhibits only a mild-moderate degree of lower eyelid laxity, might require significant supra-placement to avoid postoperative lower eyelid retraction or ectropion (Fig. 4-23). Evaluation of lower eyelid and lower periorbital subcutaneous veins should be noted and discussed if necessary, as well as the skin thickness, type, and quality. The quantification of lower eyelid skin redundancy as well as skin and orbicularis muscle laxity and descent should be made and will influence the approach. Marked skin ‘excess’ may require a greater degree of skin dissection and/or excision. Your orbicularis muscle evaluation may suggest trimming of hyperdynamic orbicularis muscle which will require enhanced canthal support (Fig. 4-24) or increased muscle suspension in situations of significant muscle laxity and ptosis (Fig. 4-25).

Assessment of asymmetry and how to best manage this

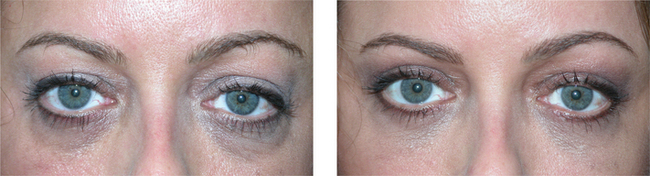

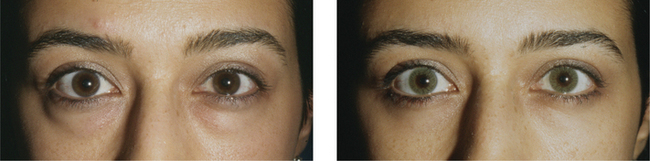

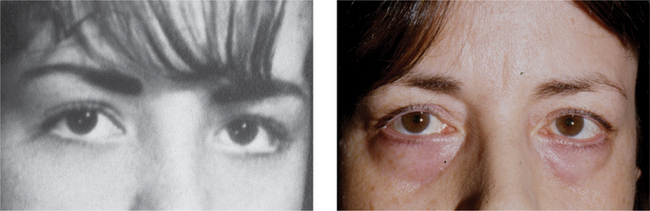

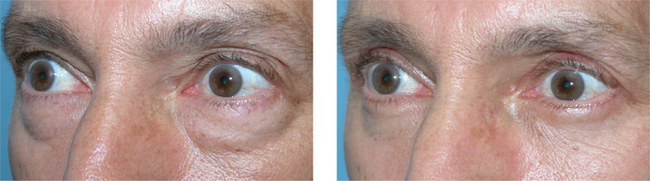

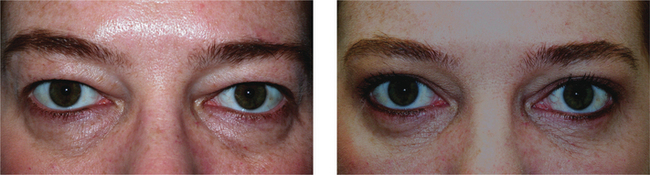

It is well known that most faces are not entirely symmetric (Fig. 4-1). The notion that the establishment of symmetry is necessary to achieve optimal results is also an historical and philosophical fallacy. Some of the most attractive people demonstrate marked facial asymmetry. Interestingly, asymmetries are well tolerated and often unnoticed in youth and much less tolerated and more obvious with age. More often, patients are unaware of their facial asymmetry but might be more keenly observant of this after surgery due, in part, to their obsession with the mirror. During the evaluation of the patient, I will usually determine this and discuss this with the patient during the treatment planning. Although not perceived by the patient, the asymmetry is sometimes a large component of their displeasure with facial aging. The assessment of asymmetry must extend far beyond the simple evaluation for blepharoptosis to achieve maximum benefit through the surgical encounter. For instance, relative or asymmetric brow ptosis may be discussed (Fig. 4-1). At times, the brow position is influenced by the upper eyelid (especially in those who reflexively elevate their ipsilateral eyebrow in response to blepharoptosis) and the upper lid ptosis is only apparent when that brow is digitally depressed by the examiner to determine the true upper eyelid position (Fig. 4-2). A patient with brow asymmetry for any reason, may also sense a greater relative amount of ‘excessive’ skin on the brow ptotic side and if this relates to brow ptosis, this should be discussed to explain the rationale for the treatment and how it relates to the chosen procedures. The side with brow ptosis is also usually the small side of the face. This must be considered, especially if the patient is having lower eyelid, mid-, or lower facial surgery. Canthal dystopia and lower eyelid position asymmetry (even in the surgically naïve patient) is also common and also more often unnoticed by the patient (see Fig. 4-1). The ‘big eye–small eye’ phenomenon (see Fig. 4-3) is also far more common than previously appreciated6 and aesthetic remedies may or may not be selected to address this. The ‘big eye’ is also usually on the large side of the face. When I detect this I ask patients what they see when they look at pictures of themselves (often this is exactly what brought them into your consulting room, but they simply have not realized this or simply can not verbalize their exact reasons for unhappiness with their appearance). Surgical and non-surgical7 maneuvers may be performed to lessen the asymmetry in the patient who is desirous of this approach. Caution must be used however with any attempt to alter the natural asymmetry in selected patients. Although an independent observer (and surgeon) might consider the subjective improvement in doing so, at times the patient feels as if they appear ‘out of balance’ much like looking at a photograph of oneself (in the days when we actually used film!) where the negative had been reversed for the printing. There is no question that this is the patient (in the photo) but the relative asymmetries that they have been accustomed to their whole life have now been altered. In general, I find the evaluation of periorbital asymmetry most useful to determine how I might titrate procedures to optimize results by either maintaining the asymmetry, or improving symmetry so that the asymmetric appearance does not become more obvious after surgery (Fig. 4-25).

Lacrimal secretory evaluation

I have not found any of the lacrimal secretory tests, including basic tear secretion with Schirmer’s tests, helpful in determining whether the patients will fare favorably after surgery performed by myself or elsewhere. Contrary to traditional teachings,1,2 I do not routinely include these tests in my practice. As we all know, patients who do very well after surgery performed with the highest of precision and care may have lacrimal secretory tests (including the Schirmer’s test) that indicate severe dryness, whereas patients who have demonstrated completely normal secretory tests and who have experienced untoward results after surgery can be dramatically symptomatic. In lieu of this, I rely heavily on an accurate history more than formal secretory function tests. The patient’s tear function is discussed (during the history and recommendations portion of the consultation and subsequent preoperative evaluations) with regard to their requirement for the use of artificial tears prior to surgery, their tolerance of contact lenses, the general symptoms with reading etc., which I find are a much greater aid in determining whether surgery is likely to impact on lacrimal function and symptomatology related to exposure. Again, female patients, especially middle-aged (nearing menopause), may be at particular risk for tipping the balance from being entirely asymptomatic to mild to moderately (and even severely) symptomatic after eyelid surgery (due to reduced lacrimal secretion that is hormonally mediated) as are those individuals who have had refractive surgery and must be reminded and warned of this. At times this particular subset of patients are actually of greater risk then the more elderly who have either adapted or compensated for the (preoperative) onset of dry eye symptoms. The possibility of intolerability to future contact lens use (especially in secondary blepharoplasty patients) should also be discussed, although I have found this less of a problem in my practice. The questions and issues regarding potential dryness after surgery, however, should be discussed with every patient so that should these symptoms occur (which are typically transient) the patient is less alarmed and realizes that the effects are usually temporary. Finally, aesthetic blepharoplasty rarely improves dry eye symptoms and patients should be made aware (especially premenopausal women) that the likely possibility of temporary and the rare incidence of worsening of dry eye symptoms exist even when surgery is satisfactory from an aesthetic standpoint.

Visual field testing

At times when patients are undergoing cosmetic blepharoplasty combined with true blepharoptosis repair (see Chapters 10 and 11), visual field tests can be obtained either by the treating surgeon or the patient’s ophthalmologist to determine if the lid malposition causes any significant visual deficit. This can be documented and submitted either by or for the patient (in a rare situation) for the consideration of insurance benefits. Either automated (Humphrey, Octopus etc.) or manual (Goldmann) field test can be obtained and similar information can be derived. Typically the tests are performed with the patient in their natural position (with upper lid malposition) and then the test is repeated with the lid taped into its normal position to determine a certain degree of visual field improvement. This continues to be a bit of a ‘gray area’ and is highly dependent upon the skill of the technician performing these tests and influenced by the will of the patient. An insightful and experienced evaluation of the results of these tests relative to the eyelid measurements can often determine the integrity of these findings.

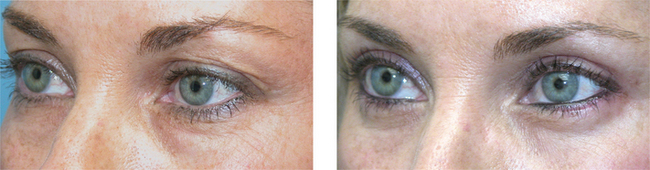

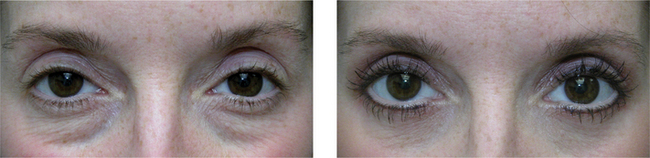

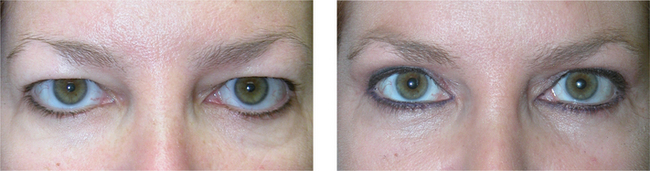

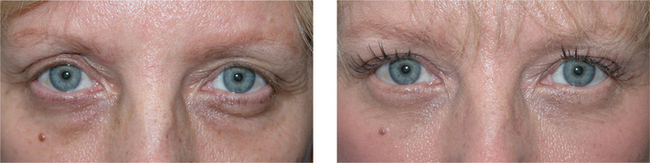

Assessment by photography

Accurate and comprehensive photography is essential for a variety or reasons, including preoperative counseling, preoperative study by the physician, documentation of the present situation including pre-existing pathology (i.e. asymmetry), as well as being a rewarding gift to the patient following surgery so that they can fully appreciate their improvement. The patient’s periorbital appearance should be photographed in primary position (Fig. 4-9) as well as oblique peri-orbital views (Fig. 4-10) to reveal to both the treating surgeon and patient the balance prior to and achieved after surgery. It is helpful to illustrate the patients relaxed and animated (especially when their complaints include dynamic facial lines that are less effected/improved by surgery) (Figs 4-18 and 4-20). For valid comparison, it is optimal (although not always possible) to have the patient photographed without cosmetic (make-up) application in both the pre- and postoperative photos. In situations where cosmetics have been applied (and the patient prefers not to remove them) during the preoperative photographic assessment, the ‘after’ photos are more easily compared with the cosmetic application; however the validity of the details of improvement that relate to the surgical efforts may be diminished.

1 Fagien S. The follow-up on ‘The value of tear film breakup and Schirmer’s tests in preoperative blepharoplasty’ by McKinney P, Byun M. Plast Reconst Surg [Discussion]. 1999;104:1.

2 Fagien S. Reducing the incidence of dry eye symptoms after blepharoplasty. Aesthetic Surg J. 2004;24:464.

3 Fagien S. Advanced rejuvenative upper blepharoplasty: enhancing aesthetics of the upper periorbita. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:278.

4 Fagien S. Eyebrow analysis after blepharoplasty in patients with brow ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8:210.

5 Fagien S. Algorithm for canthoplasty. The lateral retinacular suspension: a simplified suture canthopexy. Plast Reconst Surg. 1999;103:2042.

6 Fagien S. Temporary management of upper lid ptosis, lid malposition, and eyelid fissure asymmetry with botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1892.

7 Fagien S. Botulinum toxin type A for facial aesthetic enhancement: role in facial shaping. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(Suppl.):6S.