Problem 50 A collapsed, breathless woman

The patient arrives on an ambulance stretcher and is wheeled straight into the resuscitation bay.

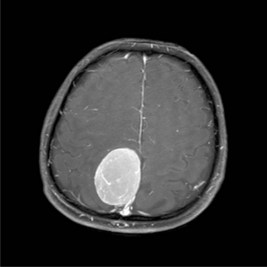

You note the following on a rapid focused examination of the patient:

Answers

A Glasgow Coma Scale score estimation is also performed as a guide of cerebral function.

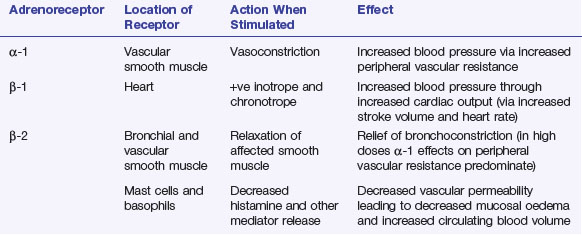

Adrenaline – the Silver Bullet in Anaphylaxis

Dunn R, Dilley S, Brookes J, et al, editors. The emergency medicine manual. Australia: Venom Publishing, Tennyson, 2003. Textbook with comprehensive notes on the pathophysiology of anaphylaxis

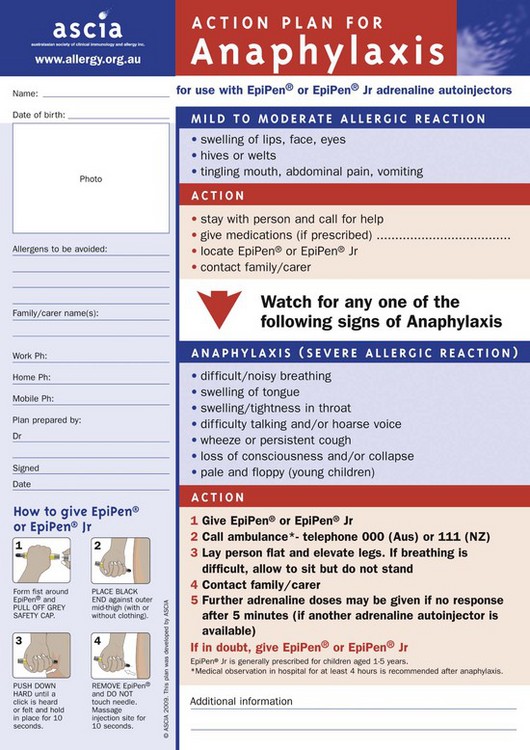

www www.allergy.org.au. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA): an excellent resource for both doctors and patients on the many issues involved in anaphylaxis including a number of action plans that can be printed off and used by patients