Problem 44 A 68-year-old woman with a left hemiplegia following a conscious collapse

You continue your history and examination.

Cardiovascular and general examination is normal.

Q.3

What investigations would you order?

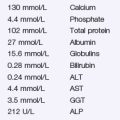

Apart from a blood sugar of 9.6 mmol/L and evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG, her blood tests and ECG are unremarkable. Other investigations are shown in Figure 44.1–3.

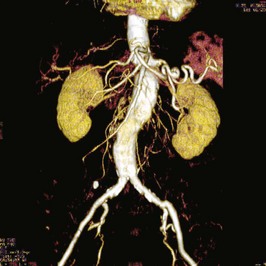

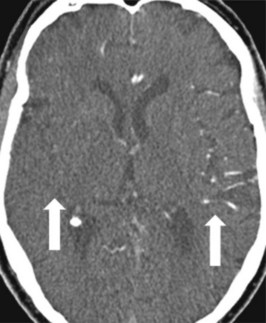

CTA performed at admission demonstrated only mild atherosclerotic carotid disease. A follow-up CT scan demonstrated a moderate area of infarction within the basal ganglia, and several small cortical areas of infarction (see Figure 44.4), somewhat less than would have been expected from her initial scan. The MCA appeared patent. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated an enlarged left atrium, but no thrombus. Fasting blood glucose was 6.2 mmol/L and a HBA1C was 7.8%. Total cholesterol was 5.2, with an LDL of 3.2 mmol/L and HDL of 0.8 mmol/L. While on the ward, 3 days after admission, a rapid and irregular pulse was noted. ECG confirmed atrial fibrillation.

Answers

Underlying cardiovascular risk factors should be established, and a general examination performed.

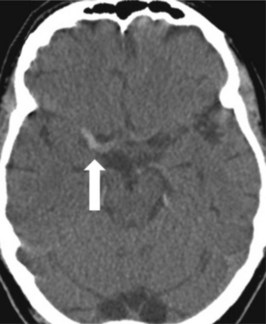

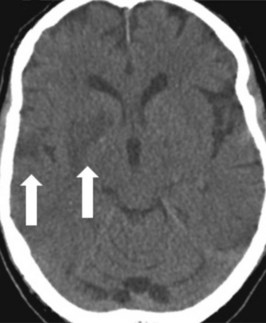

A.4 The CT scan is normal, except for a linear hyperdensity in the region of the right middle cerebral artery (see Figure 44.1) (the so-called ‘string sign’), and subtle blurring of grey–white differentiation of the medial lentiform nucleus (see Figure 44.2). The CTA demonstrated occlusion of the proximal MCA (not shown) and, more superiorly, significant hypoperfusion of the entire right MCA territory (see Figure 44.3). These findings are consistent with ischaemic stroke. Plain CT is insensitive for cerebral ischaemia in the acute phase, but hypoperfused and infarcted areas can be demonstrated with CT angiography and perfusion imaging. Extensive areas of CT hypodensity represent already infarcted tissue; thrombolysis in this setting is unlikely to be effective, and is more likely to cause haemorrhagic transformation of the infarcted area.

Revision Points

Level 1 evidence supports the following acute interventions in ischaemic stroke:

Other proven secondary prevention interventions include:

hours of stroke onset has recently been confirmed in multicentre trials. She should receive the accepted dose (0.9 mg/kg over an hour with the first 10% as a bolus).

hours of stroke onset has recently been confirmed in multicentre trials. She should receive the accepted dose (0.9 mg/kg over an hour with the first 10% as a bolus).