Problem 10 A 54-year-old man with a high-voltage electrical conduction injury

Q.2

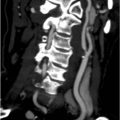

The patient was intubated and ventilated and a urinary catheter inserted in preparation for transport. His blood pressure was 125/80 mmHg with a pulse rate of 130/min. His clothes were removed to allow an accurate assessment to be made of the extent and severity of his injuries. The photographs show the burned areas of his buttocks, left knee and right foot (Figures 10.1–10.3). There was a 6 cm burn on the scalp with a similar appearance to those on his buttocks. His back had four similar burns. The changes to the left foot resembled those seen on the right foot. Five similar-sized burns were present on the upper limbs. Blood samples were collected for haemoglobin estimation, cross-matching, serum electrolytes and creatinine kinase.

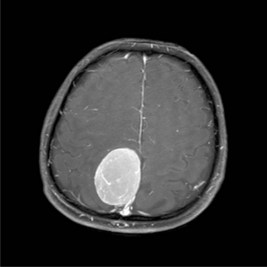

His urine output was 1 mL/kg/hour (appropriate for an adult); its appearance is shown in Figure 10.5.

Q.5

Comment on the appearance of the urine, the likely cause, and state what measures need to be taken.

Answers

A.2 The initial assessment (primary survey) must assess:

Revision Points