Problem 6 A 42-year-old woman with hypertension

The following results are available.

Investigation 6.1 Summary of results

| Fasting glucose (3.8–5.5 mmol/L) | 10 |

| Urea (2.7–8.0 mmol/L) | 7.3 |

| Creatinine (50–120 µmol/L) | 68 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | >60 |

| Ionized calcium (1.1–1.25 mmol/L) | 1.31 |

| Total calcium (2.10–2.55 mmol/L) | 2.75 |

| Phosphate (0.65–1.45 mmol/L) | 1.27 |

| Plasma metanephrine | 18 100 pmol/L (<500 pmol/L) |

| Plasma normetanephrine | 9260 pmol/L (<900 pmol/L) |

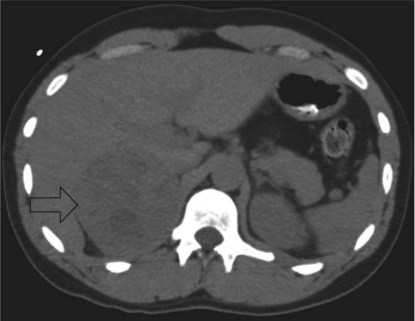

Some imaging studies are arranged and a CT scan of the abdomen performed. A representative slice is shown (Figure 6.1).

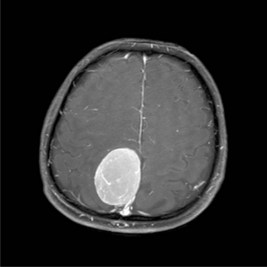

She undergoes a laparoscopic adrenalectomy and the large adrenal tumour is removed intact. As soon as the adrenal vein is ligated the blood pressure falls and the anaesthetist is able to reduce the alpha blockade. The opened surgical specimen is shown (Figure 6.2).

All medications are stopped immediately postoperatively.

Answers

She must be investigated for a secondary cause of hypertension.

A.2 The following components of the history should be clarified:

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| ‘Classic triad’ – episodic headache, sweating, tachycardia (palpitations) | Hypertension (essential or paroxysmal) |

| Diaphoresis | |

| Tremor | |

| Tachycardia |

Table 6.2 Cushing’s syndrome – hypercortisolism

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

The priority of management of this patient is treatment of the phaeochromocytoma.

With appropriate endocrine consultation the principles of management are:

A.8 Serum metanephrines should be checked to determine whether she has been cured. There is a risk of recurrence – which is highest in younger patients, those with extra-adrenal or familial disease, or bilateral and/or large tumours. Recommendations are increasingly being made that patients with phaeochromocytoma should undergo long-term surveillance (10 years in sporadic phaeochromocytoma and indefinitely in familial disease) (Lenders et al. 2005). This patient will also need a fasting blood glucose and serum calcium levels checked, as both were elevated preoperatively. If she remains hypercalcaemic then she will need investigation for primary hyperparathyroidism. If a repeat fasting blood glucose level is elevated, then this is diagnostic of diabetes mellitus.

Revision Points

Alderazi Y., Yeh M.W., Robinson B.G., et al. Phaeochromocytoma: current concepts. Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;183:201-204. Available online at http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/183_04_150805/ald10166_fm.html

Lenders J.W.M., Eisenhofer G., Mannelli M. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665-675.