Problem 26 A 41-year-old man involved in a car crash

Your examination reveals the following:

A second wide-bore intravenous cannula is inserted into a peripheral vein and 1 L of a crystalloid solution administered rapidly. Blood samples are collected for cross-matching, complete blood picture and biochemistry. In addition forensic blood alcohol samples are obtained. The chest X-ray is shown in Figure 26.1.

The initial laboratory results are also unremarkable and his haemoglobin is 131 g/L.

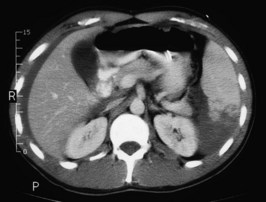

A CT scan of his head, cervical spine, chest, abdomen and pelvis is performed. A slice from the upper abdomen is shown in Figure 26.2.

Answers

In this situation the following potential complications must be remembered:

Flail Segment

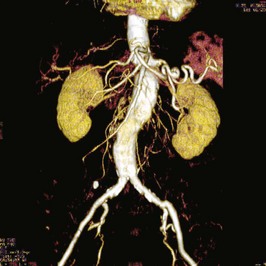

When scanning this patient it is likely that he would receive a ‘full body scan’, i.e. a scan of his head to look for cerebral contusions or bleeds, of the cervical spine to clear his neck (see Issues to Consider), of the chest to look at the extent of chest injury, and of the abdomen and pelvis to assess for intra-abdominal injury.

Revision Points

Issues to Consider

Stiell I.G., Clement C., McKnight R.D., et al. The Canadian C-spine rule vs the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:2510-2518.

Wahl W.L., Ahrns K.S., Chen S., et al. Blunt splenic injury: operation versus angiographic embolization. Surgery. 2004;136(4):891-899.

, www.trauma.org/. An independent, non-profit organization providing global education, information and communication resources for professionals in trauma and critical care