Problem 35 A 35-year-old woman vomiting blood

It is 7 p.m. on a busy Saturday night. You are called urgently to the emergency department. A 35-year-old woman has been brought in by her husband. She has vomited bright red blood on three occasions over the last 2 hours. The last episode was on arrival in the resuscitation room. The nurses say it was around 500 mL. She is pale but conscious with a GCS of 15. Her pulse is 120 and her blood pressure is 96/57 mmHg. She has an oxygen saturation of 94% on room air.

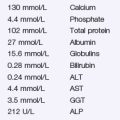

Blood tests become available as follows:

Investigation 35.1 Summary of results

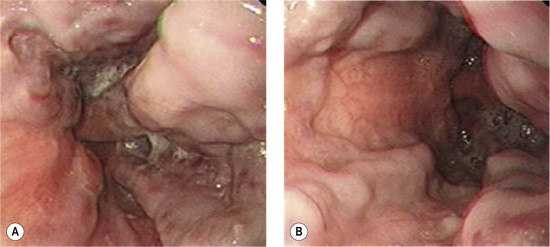

You organize an urgent endoscopy. The endoscopist finds a large amount of fresh and altered blood in the stomach. No bleeding source is identified in the stomach or the duodenum. Figure 35.1A, B shows the positive findings.

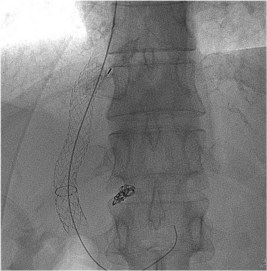

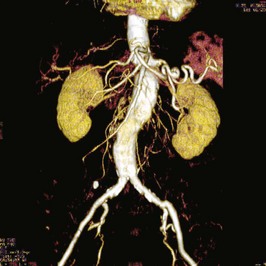

The following morning a definitive procedure is performed. An image taken from this procedure is shown (Figure 35.2).

Revision Points

Management of Variceal Haemorrhage

Airway and Breathing

Resuscitation

Vasoconstrictors

Antibiotics

• All patients with a confirmed variceal haemorrhage must receive parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotics.

• There is excellent evidence that this prevents the late septic complications which lead to renal failure, hepatic decompensation and death. There is even evidence that sepsis, for example from spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in a patient with ascites, may be the trigger that leads to increased portal blood flow and bleeding in the first place.

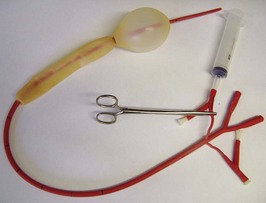

Balloon Tamponade

• ‘Sengstaken’ or ‘Minnesota’ tubes (Figure 35.3) can be life-saving but in inexperienced hands may be extremely dangerous and should always be placed by experienced operators in an intubated patient.