Problem 46 A 31-year-old man with sudden onset headache and vomiting

The patient required intravenous morphine and midazolam for the radiological investigation.

Endovascular coiling was attempted in the patient but was technically unsuccessful.

Answers

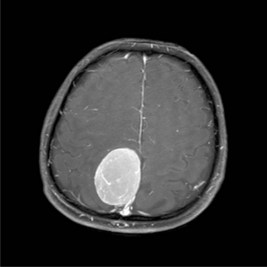

A.4 The CT head shows diffuse subarachnoid haemorrhage around the brainstem.

Issues to Consider

Bederson J.B., Awad I.A., Wiebers D.O. Recommendations for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Circulation. 2000;102:2300-2308.

Inagawa T., Kamiya K., Ogasawara H., Yano T. Rebleeding of aneurysms in the acute stage. Surgical Neurology. 1987;28(2):93-99.

Rinkel G.J., Djibuti M., Algra A., van Gijn J. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a systemic review. Stroke. 1998;29:251-256.