2.6 Neonatal resuscitation

Introduction

Epidemiology

The majority of circumstances where newborn resuscitation is needed can be predicted, allowing opportunity for preparation of appropriate equipment and personnel. Factors placing the newborn at high risk for neonatal resuscitation include those listed in Table 2.6.1, due to maternal, fetal and intrapartum circumstances.

IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation.

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The sequence of physiological changes in the newborn around birth includes:

This normal sequence may be interrupted at any point by:

Preparation

Summon assistance: if it is anticipated that the infant is at high risk of requiring advanced life support resuscitative intervention, more than one experienced person should be mobilised.

Summon assistance: if it is anticipated that the infant is at high risk of requiring advanced life support resuscitative intervention, more than one experienced person should be mobilised. In the case of extreme prematurity (≤24 weeks’ gestation) or known congenital anomalies, if time allows, the most senior care provider should seek to discuss with the family their beliefs and desires regarding the extent of resuscitation.1

In the case of extreme prematurity (≤24 weeks’ gestation) or known congenital anomalies, if time allows, the most senior care provider should seek to discuss with the family their beliefs and desires regarding the extent of resuscitation.1HSA, human serum albumin; PPV, positive pressure ventilation.

Assessment at birth

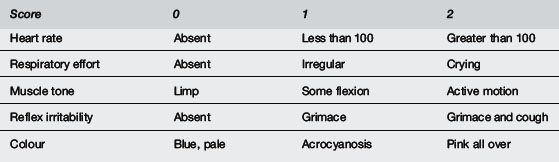

At birth the infant should be collected in a warm towel, dried and the umbilical cord clamped. Gentle stimulation may be provided (rubbing the back, flicking soles of feet if required) and an assessment of initial cry, respiratory effort, heart rate, colour and tone should be made virtually simultaneously (Table 2.6.3).

Ventilation

The initial assessment is an evaluation of the presence and quality of respirations.

Heart rate

Colour

Muscle tone and reflex irritability

These physical signs are valuable composite reflections of the adequacy of cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. As such, they constitute two of the five components of the Apgar score (see Table 2.6.3) used to assess a newborn’s condition after birth.

Medications

Volume expansion

If hypovolaemia is present because of known or suspected blood loss or loss of vascular tone following asphyxia, volume expansion may be appropriate. Isotonic non-dextrose containing crystalloid (normal saline or Ringer’s lactate) 10 mL kg–1 intravenously over 5–10 minutes is recommended. Group O negative packed red cells may be indicated for replacement of large volume blood loss. Albumin-containing solutions are used less frequently because of limited availability, risk of infectious disease and an observed association with increased mortality. A recent randomised controlled comparison of albumin versus normal saline for hypotension in premature newborns showed that those who received albumin required significantly more volume expander to maintain normal blood pressure and had a higher mean percentage weight gain in the first 48 hours after birth.3

Specific resuscitation situations

Premature neonate

Preterm newborns have an increased likelihood of respiratory depression requiring assisted ventilation at birth. This occurs because of diminished lung compliance, weak respiratory muscles and immature respiratory drive and may make it difficult to establish and maintain an adequate FRC. For these reasons, infants born at or before 32 weeks gestation should receive face mask resuscitation by 30 seconds and be intubated at 60 seconds after birth if the onset of adequate spontaneous respirations is delayed. A recent study has shown that CPAP applied promptly to premature babies who breathe at birth may be effective in reducing need for ventilation. Also, because preterm infants often have low body fat and a high body surface area to mass ratio, they are more difficult to keep warm and therefore at increased risk of cold stress. For this reason babies <1500 g should be covered in food-grade heat-resistant plastic wrapping or placed in a polyethylene bag with the head excluded and a hat placed on the head. Rapid boluses of volume expander and use of hyperosmolar solutions may produce large fluctuations in blood pressure or osmolarity and therefore are not recommended.3

Congenital heart disease

Detailed cardiac auscultation should be attempted though there may be no abnormal murmurs audible; simultaneous pre- and postductal oximetry measurements should be performed. If a cyanotic cardiac abnormality is strongly suspected, documentation of preductal PaO2 after breathing 100% oxygen for several minutes (hyperoxia test) will give the best indication of the presence and size of a significant intracardiac right to left shunt (see Chapter 5.1). An urgent bedside echocardiogram, if available, is indicated to delineate the cardiac anatomy. Where this is not available, one should consult with the local tertiary neonatal unit. If a diagnosis of a duct-dependent cyanotic cardiac lesion is confirmed on echocardiogram, IV alprostadil (PGE1) 25–50 ng kg–1 min–1 restores and maintains ductal patency until definitive decisions regarding surgical correction can be made. The main side effects of this medication are flushing, fever and possibly apnoea if respiratory support is not already in place.

Alternatively, babies with duct-dependent systemic circulation usually due to some structural problem with left ventricular outflow (e.g. critical aortic stenosis, severe coarctation, hypoplastic left heart syndrome) may present in the first few days of life with heart failure and poor peripheral perfusion triggered by ductal closure. The most reliable physical signs of heart failure are tachycardia, tachypnoea and hepatomegaly. If shock is present (poor pulse volume, pallor, altered conscious state) respiratory support and fluid volume expansion may be required to restore the circulation. Subsequently, alprostadil or inotrope infusion and continuing judicious fluid administration may be required. The most important steps in restoring systemic circulation in this situation are artificial ventilation to normocapnia, together with re-establishing and maintaining ductal patency (see Chapter 5.5).

Post-resuscitation stabilisation

Prognosis

Air or O2 for newborn resuscitation. Traditionally, 100% oxygen has been used for neonatal resuscitation, but recent animal studies and human trials have confirmed that ventilation with room air is equally successful in neonatal resuscitation. Use of air may have advantages (reduced oxidative stress, less delay in onset of spontaneous respirations). There may still be situations in which 100% oxygen is advantageous (pulmonary hypertension, diffusion abnormalities, alterations in cerebral blood flow). At present best evidence suggests that air should be used initially with supplementary oxygen if the infant’s condition does not improve after effective ventilation. Data suggest that oxygen use in neonatal resuscitation should be individualised with the dose tailored to clinical response and monitored by oximetry.2

Air or O2 for newborn resuscitation. Traditionally, 100% oxygen has been used for neonatal resuscitation, but recent animal studies and human trials have confirmed that ventilation with room air is equally successful in neonatal resuscitation. Use of air may have advantages (reduced oxidative stress, less delay in onset of spontaneous respirations). There may still be situations in which 100% oxygen is advantageous (pulmonary hypertension, diffusion abnormalities, alterations in cerebral blood flow). At present best evidence suggests that air should be used initially with supplementary oxygen if the infant’s condition does not improve after effective ventilation. Data suggest that oxygen use in neonatal resuscitation should be individualised with the dose tailored to clinical response and monitored by oximetry.2 Hypothermia. Traditionally, post-resuscitation care has involved heat-loss prevention or even external warming on the basis that this facilitates recovery from acidosis. However, recent animal studies have clearly shown that early modest cerebral hypothermia (32–34°C) can modulate hypoxic ischaemic injury. Studies in human neonates are accumulating regarding the safety of induced hypothermia. At present cerebral hypothermia can not be routinely recommended. However, hyperthermia should definitely be avoided as there is strong evidence that this is deleterious.4

Hypothermia. Traditionally, post-resuscitation care has involved heat-loss prevention or even external warming on the basis that this facilitates recovery from acidosis. However, recent animal studies have clearly shown that early modest cerebral hypothermia (32–34°C) can modulate hypoxic ischaemic injury. Studies in human neonates are accumulating regarding the safety of induced hypothermia. At present cerebral hypothermia can not be routinely recommended. However, hyperthermia should definitely be avoided as there is strong evidence that this is deleterious.4 Ethics of resuscitation. The decision to withdraw or withhold resuscitation from extremely premature newborns or those with severe congenital abnormalities requires clear communication with the family and accurate clinical data. Overall there is agreement that overly aggressive treatment is to be discouraged.1

Ethics of resuscitation. The decision to withdraw or withhold resuscitation from extremely premature newborns or those with severe congenital abnormalities requires clear communication with the family and accurate clinical data. Overall there is agreement that overly aggressive treatment is to be discouraged.1 Recent studies demonstrate extremely poor survival rates for infants less than 23 weeks gestation (<1%) with a better but still poor rate for infants admitted to the NICU (5%). Mortality is less at 23, 24 and 25 completed weeks (11%, 26% and 44% survival in one large recent study). However, severe disability in childhood is present in 20 to 30% of survivors at these gestations and some disability can be expected in 50%.5 Prognosis is probably better predicted by gestational age (if accurately known) rather than weight, though both factors have a role and gender is also important (lower mortality/morbidity in females).

Recent studies demonstrate extremely poor survival rates for infants less than 23 weeks gestation (<1%) with a better but still poor rate for infants admitted to the NICU (5%). Mortality is less at 23, 24 and 25 completed weeks (11%, 26% and 44% survival in one large recent study). However, severe disability in childhood is present in 20 to 30% of survivors at these gestations and some disability can be expected in 50%.5 Prognosis is probably better predicted by gestational age (if accurately known) rather than weight, though both factors have a role and gender is also important (lower mortality/morbidity in females). Non-initiation of resuscitation in the delivery room is appropriate for infants with confirmed gestation less than 23 weeks or birth weight less than 400 g, anencephaly or confirmed trisomy 13 or 18. Options include a trial of resuscitation, non-initiation or discontinuation after further assessment. Initiation of resuscitation does not mandate continued support.

Non-initiation of resuscitation in the delivery room is appropriate for infants with confirmed gestation less than 23 weeks or birth weight less than 400 g, anencephaly or confirmed trisomy 13 or 18. Options include a trial of resuscitation, non-initiation or discontinuation after further assessment. Initiation of resuscitation does not mandate continued support.1 Boyle R.J., Mcintosh N. Ethical considerations in neonatal resuscitation: clinical and research issues. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:261-269.

2 Richmond S., Goldsmith J.P. Air or 100% oxygen in neonatal resuscitation? Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:11-28.

3 So K.W., Fok T.F., Ng P.C., et al. Randomised controlled trial of colloid or crystalloid in hypotensive preterm infants. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:F43-F46.

4 Hoehn T., Hansmann G., Buhrer C., et al. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonates. Review of current clinical data, ILCOR recommendations and suggestions for implementation in neonatal intensive care units. Resuscitation. 2008;78:7-12.

5 Wood N.S., Marlow N., Costeloe K., et al. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(6):378-384.

Escobedo M. Moving from experience to evidence: changes in US Neonatal Resuscitation Programme based on International Committee on Resuscitation Review. J Perinatol. 2008;28:S35-40.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The International Liason Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e978-988.

Richmond S. ILCOR and Neonatal Resuscitation 2005. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F163-F165.

Wu T.J., Carlo W.A. Neonatal resuscitation guidelines 2000: framework for practice. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:4-10.