CHAPTER 15 PRACTICAL PROCEDURES

GENERAL INFORMATION

Universal infection control precautions

Cuts or grazes on the hands or forearms should be covered with a waterproof dressing while at work. Seek medical advice about any septic or weeping areas.

Cuts or grazes on the hands or forearms should be covered with a waterproof dressing while at work. Seek medical advice about any septic or weeping areas. Single-use gloves should be worn for direct contact with blood or body fluid, broken skin or mucous membranes.

Single-use gloves should be worn for direct contact with blood or body fluid, broken skin or mucous membranes. Full face visors should be worn to protect against blood or body fluids that may potentially splash the face / eyes.

Full face visors should be worn to protect against blood or body fluids that may potentially splash the face / eyes. Place all sharps directly into a sharps bin; do not manually resheath or break needles. Do not overfill sharps bins, and ensure that the bin is securely fastened before disposal.

Place all sharps directly into a sharps bin; do not manually resheath or break needles. Do not overfill sharps bins, and ensure that the bin is securely fastened before disposal.ARTERIAL CANNULATION

Indications

Procedure

Arterial cannulation. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gloves

Syringe of local anaesthetic / needle

Syringe of heparinized saline flush

Arterial cannulae (usually 20 gauge or 22 gauge)

Decide which artery to cannulate. The radial artery of the non-dominant hand is usually preferred in the first instance. Alternatives include the ulnar, dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries. It is pointless, however, to persist with attempts at peripheral arterial cannulation in patients who are hypotensive and ‘shut down’. The femoral and brachial arteries are useful during resuscitation of profoundly shocked patients. Ultrasound guidance is potentially useful at all sites to aid arterial cannulation, particularly in hypotensive patients and those whose landmarks are obscured by oedema or obesity.

Gently palpate the artery and inject local anaesthetic to raise a small intradermal bleb at the puncture site 1 cm distal to the proposed cannulation site.

Gently palpate the artery and inject local anaesthetic to raise a small intradermal bleb at the puncture site 1 cm distal to the proposed cannulation site.Seldinger technique

Advance needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured, a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Pass the guide wire through the needle into the artery. Withdraw the needle and pass the cannula over the guide wire. The guide wire is then discarded.

Advance needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured, a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Pass the guide wire through the needle into the artery. Withdraw the needle and pass the cannula over the guide wire. The guide wire is then discarded.Direct cannulation

Either: advance the cannula and needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Holding the needle still, advance the cannula over the needle into the artery. This should be a single smooth movement without resistance.

Either: advance the cannula and needle through the puncture site towards the artery at a shallow angle. As the vessel is punctured a flashback of arterial blood is seen in the hub. Holding the needle still, advance the cannula over the needle into the artery. This should be a single smooth movement without resistance. Or: advance the cannula at a steeper angle and, after observing the flashback, continue through the artery to transfix it. Withdraw the needle slightly from the cannula and then pull the cannula back gently until the tip is in the artery and flashback is again observed. Advance the cannula into the artery.

Or: advance the cannula at a steeper angle and, after observing the flashback, continue through the artery to transfix it. Withdraw the needle slightly from the cannula and then pull the cannula back gently until the tip is in the artery and flashback is again observed. Advance the cannula into the artery.Sampling from an arterial line

USE OF PRESSURE TRANSDUCERS

The patient’s arterial catheter is connected to the transducer by a continuous column of (heparinized) saline. A pressurized flushing device maintains a small forward flow (approximately 2–3 mL / h) to keep the cannula patent.

The patient’s arterial catheter is connected to the transducer by a continuous column of (heparinized) saline. A pressurized flushing device maintains a small forward flow (approximately 2–3 mL / h) to keep the cannula patent. Pressure changes in the vessel are transmitted via the saline to a diaphragm. As this diaphragm moves in response to the pressure changes, its electrical conductivity changes. This results in fluctuations in electrical signal from the diaphragm, which is interpreted by a monitor and displayed as an arterial waveform and blood pressure values. Systolic, diastolic and mean pressures are usually displayed.

Pressure changes in the vessel are transmitted via the saline to a diaphragm. As this diaphragm moves in response to the pressure changes, its electrical conductivity changes. This results in fluctuations in electrical signal from the diaphragm, which is interpreted by a monitor and displayed as an arterial waveform and blood pressure values. Systolic, diastolic and mean pressures are usually displayed. There must be no air bubble in the connection tubing or transducer chamber. This will damp the trace and produce lower blood pressure values. Flush well before connecting the transducer to the patient.

There must be no air bubble in the connection tubing or transducer chamber. This will damp the trace and produce lower blood pressure values. Flush well before connecting the transducer to the patient. The transducer should be maintained at the level of the left atrium and appropriately zeroed. (If raised above this level the recorded pressure will be too low, and vice versa.)

The transducer should be maintained at the level of the left atrium and appropriately zeroed. (If raised above this level the recorded pressure will be too low, and vice versa.)Zeroing transducers

To zero a transducer turn the three-way tap so the transducer is open to air and the patient connection is switched off. The transducer is now connected to atmospheric or zero gauge pressure.

To zero a transducer turn the three-way tap so the transducer is open to air and the patient connection is switched off. The transducer is now connected to atmospheric or zero gauge pressure.CENTRAL VENOUS CANNULATION

Indications

Central venous access is almost universal in intensive care patients. Indications include:

Ultrasound guidance for vascular access

The use of ultrasound to guide central venous access procedures is recommended in all cases (NICE Guidance. Central venous catheters, ultrasound locating devices, Sept. 2002. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA49).

Ensure correct orientation of the probe (vessels should be in the anatomical orientation as it would appear from where you are standing.

Ensure correct orientation of the probe (vessels should be in the anatomical orientation as it would appear from where you are standing. Identify patent target vessel. (To exclude thrombus in a vein ensure it empties completely with pressure.)

Identify patent target vessel. (To exclude thrombus in a vein ensure it empties completely with pressure.) Puncture the vessel of choice using real time guidance to direct the needle into the vein using longitudinal or transverse approaches.

Puncture the vessel of choice using real time guidance to direct the needle into the vein using longitudinal or transverse approaches.Traditional approaches to the central veins are described below.

Internal jugular vein

Right sided internal jugular vein cannulation is associated with a lower incidence of complications and higher incidence of correct line placement than other approaches. It is especially appropriate for patients with coagulopathy or those patients with lung disease in whom pneumothorax may be disastrous. It may be best avoided in those patients with carotid artery disease or those with raised intracranial pressure because of the risks of carotid puncture and of impaired cerebral venous drainage. Internal jugular cannulation is associated with a higher incidence of catheter infection than subclavian cannulation but both have a much lower infection rate than the femoral approach.

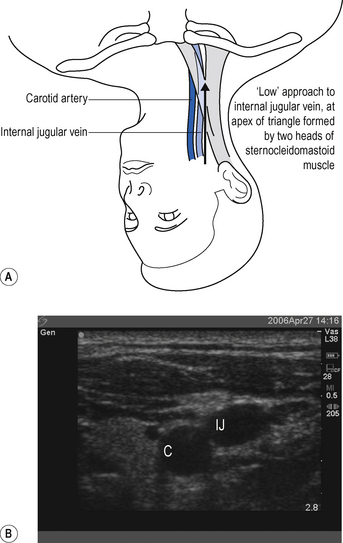

The internal jugular vein runs from the jugular foramen at the base of the skull (immediately behind the ear) to its termination behind the posterior border of the sternoclavicular joint, where it combines with the subclavian vein to become the brachiocephalic vein. Throughout its length it lies lateral, first to the internal and then common carotid arteries, within the carotid sheath, behind the sternomastoid muscle (Fig. 15.1A). Ultrasound demonstrates the close proximity of the vein to the carotid artery (Fig. 15.1B). Many approaches to the internal jugular vein have been described. A typical landmark approach is from the apex of the triangle formed by the two heads of the sternomastoid (Fig. 15.1).

Look for the internal jugular vein pulsation. If compressed, the internal jugular can usually be seen to empty and refill.

Look for the internal jugular vein pulsation. If compressed, the internal jugular can usually be seen to empty and refill. Introduce the needle from the apex of the triangle at an angle of 30° and aim towards the ipsilateral nipple.

Introduce the needle from the apex of the triangle at an angle of 30° and aim towards the ipsilateral nipple. Often when attempting to puncture the vein it collapses under the pressure of the needle and puncture is not recognized. The vessel may then be located by aspirating as the needle is slowly withdrawn. Blood is aspirated as the needle tip passes back into the vein, which refills once the pressure has been removed.

Often when attempting to puncture the vein it collapses under the pressure of the needle and puncture is not recognized. The vessel may then be located by aspirating as the needle is slowly withdrawn. Blood is aspirated as the needle tip passes back into the vein, which refills once the pressure has been removed. Typical catheter length required is 15 cm from the right and 20 cm from the left. The right side is preferred because left-sided catheters have to traverse two ‘corners’ to get to the SVC and are associated with a higher complication rate.

Typical catheter length required is 15 cm from the right and 20 cm from the left. The right side is preferred because left-sided catheters have to traverse two ‘corners’ to get to the SVC and are associated with a higher complication rate.External jugular vein

The external jugular vein lies superficially in the neck, running down from the region of the angle of the jaw, across the sternomastoid before passing deep to drain into the subclavian vein. It can be used to provide central venous access, particularly in emergency situations when a simple large-bore cannula can be used for the administration of drugs and resuscitation fluids. Longer central venous catheters can be sited via the external jugular but the angle of entry to the subclavian vein often leads to inability to pass guide wires centrally and results in a high failure rate.

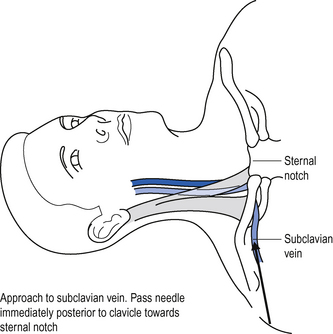

Subclavian vein

The subclavian vein is a continuation of the axillary vein. It runs from the apex of the axilla behind the posterior border of the clavicle and across the first rib to join the internal jugular vein, forming the brachiocephalic vein behind the sternoclavicular joint. See Fig. 15.2.

Position the patient supine (some people advocate placing a sandbag between the patient’s shoulder blades, which allows the shoulders to drop back out of the way).

Position the patient supine (some people advocate placing a sandbag between the patient’s shoulder blades, which allows the shoulders to drop back out of the way). Introduce the needle just beneath the clavicle at this point, and aim towards the clavicle until contact with bone is made.

Introduce the needle just beneath the clavicle at this point, and aim towards the clavicle until contact with bone is made.Femoral vein

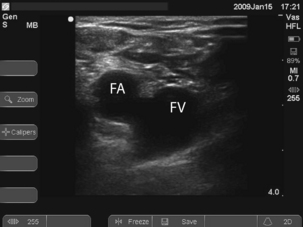

To locate the vein, introduce the needle 1 cm medial to the femoral artery close to the inguinal ligament. It is a common mistake to go too low where the superficial femoral artery overlies the vein. Long catheters, 24 cm plus, are required to get the tip of the catheter into the IVC, which may be required for good flows (e.g. for dialysis).

To locate the vein, introduce the needle 1 cm medial to the femoral artery close to the inguinal ligament. It is a common mistake to go too low where the superficial femoral artery overlies the vein. Long catheters, 24 cm plus, are required to get the tip of the catheter into the IVC, which may be required for good flows (e.g. for dialysis). Ultrasound can be used to identify the vessels and ensure that the vein is punctured near the inguinal ligament where the artery and vein lie side by side. See Fig. 15.3.

Ultrasound can be used to identify the vessels and ensure that the vein is punctured near the inguinal ligament where the artery and vein lie side by side. See Fig. 15.3.Procedure

Central venous cannulation. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

5-mL syringe of local anaesthetic

Heparinized saline to flush line

Central venous catheterization is almost universally achieved using a catheter over a guide wire (Seldinger) technique. This is associated with a lower incidence of incorrect line placement and complications than cannula over needle techniques.

Central venous catheterization is almost universally achieved using a catheter over a guide wire (Seldinger) technique. This is associated with a lower incidence of incorrect line placement and complications than cannula over needle techniques. For internal jugular, external jugular and subclavian veins position the patient supine with 10–20° head down tilt. This distends the vein to aid location and helps prevent air embolism.

For internal jugular, external jugular and subclavian veins position the patient supine with 10–20° head down tilt. This distends the vein to aid location and helps prevent air embolism. Check wire passes through the needle freely. Attach three-way taps to all open ports of the cannula. Flush the lumens with heparinized saline.

Check wire passes through the needle freely. Attach three-way taps to all open ports of the cannula. Flush the lumens with heparinized saline. Using a 10-mL syringe and needle enter the central vein by the chosen approach, maintaining suction on the syringe at all times.

Using a 10-mL syringe and needle enter the central vein by the chosen approach, maintaining suction on the syringe at all times. Pass the Seldinger wire through the needle. This should pass freely and without any force into the vein. Watch for dysrhythmias. To reduce the risk of dysrhythmias, avoid introducing the wire further than necessary.

Pass the Seldinger wire through the needle. This should pass freely and without any force into the vein. Watch for dysrhythmias. To reduce the risk of dysrhythmias, avoid introducing the wire further than necessary. Never pull the wire back through the needle once it has passed beyond the end of the bevel: it may shear off.

Never pull the wire back through the needle once it has passed beyond the end of the bevel: it may shear off. If provided, pass the dilator over the wire into the vein. Then remove it, leaving the wire in situ.

If provided, pass the dilator over the wire into the vein. Then remove it, leaving the wire in situ. Pass the cannula over the wire into the vein. Make sure that before you push the cannula forward the wire is visible at the proximal end. Hold on to the wire at all times, to prevent it being lost inside the patient!

Pass the cannula over the wire into the vein. Make sure that before you push the cannula forward the wire is visible at the proximal end. Hold on to the wire at all times, to prevent it being lost inside the patient! For an average adult patient the central venous cannula does not need to be inserted more than 12–15 cm.Check markings on the cannula. Many are 20 cm long and do not need to be inserted up to the hub.

For an average adult patient the central venous cannula does not need to be inserted more than 12–15 cm.Check markings on the cannula. Many are 20 cm long and do not need to be inserted up to the hub. Draw back blood, flush all the lumens of the line with heparinized saline and lock off the three-way taps. At this point the patient can be levelled.

Draw back blood, flush all the lumens of the line with heparinized saline and lock off the three-way taps. At this point the patient can be levelled. Suture the line into place using the anchorage devices provided and cover with an adhesive sterile dressing.

Suture the line into place using the anchorage devices provided and cover with an adhesive sterile dressing.Position on chest X-ray

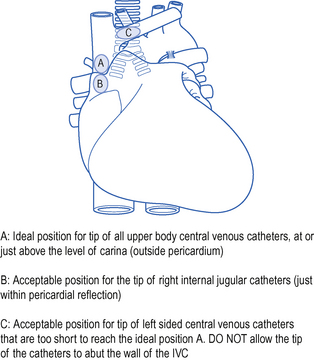

The catheter should lie along the long axis of the vessel and the distal segment and tip should be in the superior vena cava (SVC) or at the junction of the SVC and right atrium but ideally outside the pericardial reflection. Catheters below this level may perforate the heart and cause cardiac tamponade. The pericardial reflection lies below the level of the carina and this can therefore be used as a radiological marker. Catheters placed via subclavian veins of left internal jugular vein must not be allowed to lie with the tip abutting the wall of the superior vena cava. This may cause pain, perforation and accelerated thrombus formation. Either advance the catheter to lie in the long axis of the SVC or pull it back to lie in the brachiocephalic vein. See Fig. 15.4.

COMMON PROBLEMS DURING CENTRAL VENOUS ACCESS

Cannot find the vein

Check position (ultrasound and / or landmarks) and try again. If unsuccessful do not persist with repeated passages of the needle in the hope of striking oil! You may have misinterpreted the landmarks, or the vein may be absent or occluded (e.g. with thrombus). Seek help.

Complications

Complications of central venous cannulation depend in part on the route used but include those in Box 15.2.

| Early | Late |

|---|---|

| Arrhythmias | Infection |

| Vascular injury | Thrombosis |

| Pneumothorax | Embolization |

| Haemothorax | Erosion/perforation of vessels |

| Thoracic duct injury (chylothorax) | Cardiac tamponade |

| Cardiac tamponade | AV fistula |

| Neural injury | |

| Embolization (including guide wire) | |

| AV fistula |

CHANGING AND REMOVING CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERS

Line colonization with bacteria and fungi is common and there is no evidence that changing lines on a regular basis (e.g. every 5–7 days) is of benefit. (See Catheter-related sepsis, p. 340.)

Changing catheters over a wire

Pass the wire down the central lumen of the old central venous catheter. (Make sure that the new wire is longer than the old CVP line.)

Pass the wire down the central lumen of the old central venous catheter. (Make sure that the new wire is longer than the old CVP line.)LARGE-BORE INTRODUCER SHEATHS / DIALYSIS CATHETERS

Indications

Introducer sheaths are available in a number of sizes for different applications, including insertion of pulmonary artery catheters and temporary pacing wires. In adults, 7.5 or 8.5 Fr are generally used. They may be used as large-bore access for volume resuscitation. Smaller sheaths may be used for introducing specialized monitoring such as jugular bulb oximetery. Large-bore double lumen dialysis catheters are used for haemodialysis, haemofiltration, plasma exchange and rapid transfusion.

Procedure

See Central venous cannulation above.

Either: Pass the sheath mounted on the introducer / dilator over the wire into the vein. The dilator is generally longer than needed and does not need to be passed right up to the hub. When the dilator has entered the vein, slide the sheath forward without advancing the dilator any further.

Either: Pass the sheath mounted on the introducer / dilator over the wire into the vein. The dilator is generally longer than needed and does not need to be passed right up to the hub. When the dilator has entered the vein, slide the sheath forward without advancing the dilator any further. Or for dialysis catheters, pass the dilator over the wire into the vein then remove dilator and introduce catheter over the wire.

Or for dialysis catheters, pass the dilator over the wire into the vein then remove dilator and introduce catheter over the wire.PULMONARY ARTERY CATHETERIZATION

The place of pulmonary artery catheters has been questioned recently and their use has diminished. In general non-invasive cardiac output monitoring and the ready availability of bedside echocardiography have superseded them. (See Haemodynamic monitoring, p. 74.) They may be of value, however, in conditions where haemodynamic instability or shock is unresponsive to fluid and inotrope therapy guided by conventional CVP measurement, particularly where pulmonary hypertension/right heart failure are thought to contribute to the problem. As insertion of a PA catheter is not without hazard, you should always seek senior guidance. Traditional indications and contraindications are shown in Box 15.3.

Box 15.3 Indications and contraindications for pulmonary artery catheterization

| Indications | Relative contraindications |

|---|---|

| Shock | Severe coagulopathy |

| Sepsis / SIRS | Unstable ventricular rhythm |

| ARDS | Heart block |

| Valvular heart disease* | Temporary transvenous pacemaker (wire dislodgement) |

| Left ventricular failure | Stenosis tricuspid or pulmonary valve† |

| Cor pulmonale / pulmonary hypertension | |

| High-risk surgical patients |

† Severe stenosis or mechanical valves absolute contraindication.

Procedure

PA catheterization. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

5-mL syringe of local anaesthetic

Introducer sheath (see previous section)

Ultrasound/sterile probe cover and gel

Position the patient flat before inserting the PA catheter. (This reduces the pulmonary artery pressures and reduces the risk of pulmonary artery rupture.)

Position the patient flat before inserting the PA catheter. (This reduces the pulmonary artery pressures and reduces the risk of pulmonary artery rupture.) Connect 1.5 mL syringe to the balloon port and test the balloon. (Check the size of the balloon before starting.)

Connect 1.5 mL syringe to the balloon port and test the balloon. (Check the size of the balloon before starting.) Pass the proximal end of the catheter to an assistant who can connect a pressure transducer to the PA port (yellow) and flush the lumen. Then zero the transducer and check the signal on the monitor. Need to display trace on the monitor (scale 0–75 mmHg) continuously.

Pass the proximal end of the catheter to an assistant who can connect a pressure transducer to the PA port (yellow) and flush the lumen. Then zero the transducer and check the signal on the monitor. Need to display trace on the monitor (scale 0–75 mmHg) continuously. Inflate balloon and advance catheter gently to right ventricle at approximately 30–40 cm. Advance further until the pulmonary artery is entered at approximately 40–50 cm.

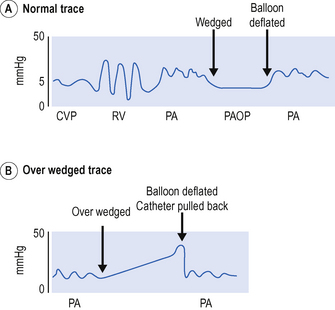

Inflate balloon and advance catheter gently to right ventricle at approximately 30–40 cm. Advance further until the pulmonary artery is entered at approximately 40–50 cm. Advance the catheter until pulmonary artery occlusion trace or wedge trace is observed, approx. 20 cm from RV (approximately 50–60 cm total). Deflate the balloon and see return of the PA trace (Fig. 15.5).

Advance the catheter until pulmonary artery occlusion trace or wedge trace is observed, approx. 20 cm from RV (approximately 50–60 cm total). Deflate the balloon and see return of the PA trace (Fig. 15.5). Once the PA catheter is in position, perform a CXR; check the position of the catheter in the proximal pulmonary artery and exclude pneumothorax / haemothorax / knotting of the line.

Once the PA catheter is in position, perform a CXR; check the position of the catheter in the proximal pulmonary artery and exclude pneumothorax / haemothorax / knotting of the line. While in use, ensure that the PA pressure trace is displayed continuously on the bedside monitor so that inadvertent ‘wedging’ of the catheter can be recognized and the catheter pulled back to prevent pulmonary infarction.

While in use, ensure that the PA pressure trace is displayed continuously on the bedside monitor so that inadvertent ‘wedging’ of the catheter can be recognized and the catheter pulled back to prevent pulmonary infarction.COMMON PROBLEMS DURING PULMONARY ARTERY CATHETERIZATION

Catheter will not take the correct path

This may be due to a dilated RV or low CO. Do not persist if unsuccessful:

Catheter is ‘over wedged’

Catheter will not wedge

This may be because the catheter is curled up within the PA. Do not pass more than 20 cm without a change in trace. Pull back and try again.

This may be because the catheter is curled up within the PA. Do not pass more than 20 cm without a change in trace. Pull back and try again. In the presence of severe mitral regurgitation or pulmonary hypertension, it may not be possible to obtain a satisfactory wedge trace and attempts may be associated with increased risk of PA rupture. Accept that the catheter will not wedge and use pulmonary diastolic pressure instead of PA occlusion pressure.

In the presence of severe mitral regurgitation or pulmonary hypertension, it may not be possible to obtain a satisfactory wedge trace and attempts may be associated with increased risk of PA rupture. Accept that the catheter will not wedge and use pulmonary diastolic pressure instead of PA occlusion pressure.Complications

Potential complications of pulmonary artery catheterization are shown in Table 15.1.

TABLE 15.1 Complications of pulmonary artery catheterization

| Complication | Comment |

|---|---|

| Central venous puncture | Any complications of central venous cannulation |

| Dysrhythmia | Usually on passage through tricuspid valve and RV Especially if hypoxia, acidosis, hypokalaemia: withdraw catheter and reposition Complete heart block may occur |

| Pulmonary infarction | Check catheter is in proximal PA on chest X-ray Never leave balloon inflated Display PA trace continuously |

| Pulmonary artery rupture | Pulmonary haemorrhage and blood up the endotracheal tube Avoid overinflation of the balloon Watch trace and never inflate against resistance |

| Infection | Risk includes endocardial damage and endocarditis Careful aseptic technique and catheter care Remove after 72 h or ASAP |

| Knotting | Poor insertion technique Do not insert more than 20 cm without a change in trace Do not attempt to pull back. Call for help |

MEASUREMENT OF CARDIAC OUTPUT BY THERMODILUTION

Ensure that the correct cables are connected between the monitor and the PA catheter (one to the distal thermistor and one to measure the temperature of the injectate).

Ensure that the correct cables are connected between the monitor and the PA catheter (one to the distal thermistor and one to measure the temperature of the injectate). Check that the correct computation constant is entered into the monitor. This depends upon the volume and temperature of the injectate and also the type of catheter used. The correct computation constant is found on the packaging information of the PA catheter.

Check that the correct computation constant is entered into the monitor. This depends upon the volume and temperature of the injectate and also the type of catheter used. The correct computation constant is found on the packaging information of the PA catheter. Set the computer to measure cardiac output, and when prompted inject 10 mL of 5% dextrose into the right atrial (CVP) lumen of the PA catheter. Time the injection at the end of inspiration and inject as rapidly as possible.

Set the computer to measure cardiac output, and when prompted inject 10 mL of 5% dextrose into the right atrial (CVP) lumen of the PA catheter. Time the injection at the end of inspiration and inject as rapidly as possible. Repeat the measurement. The individual cardiac output values obtained should not vary more than 5% from each other. Discard any inconsistent value and take the average reading for cardiac output.

Repeat the measurement. The individual cardiac output values obtained should not vary more than 5% from each other. Discard any inconsistent value and take the average reading for cardiac output.Having measured the cardiac output and PA occlusion pressure a range of haemodynamic variables can be calculated. This is generally performed by the monitoring system. Normal values for these variables are given in Chapter 4. (See Optimizing haemodynamic status, p. 78.)

PERICARDIAL ASPIRATION

Procedure

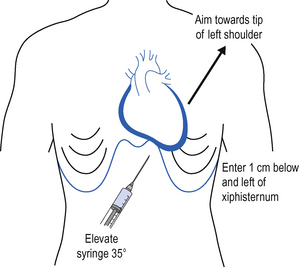

The point of needle insertion is immediately below and to the left of the xiphisternum, between the xiphisternum and the left costal margin. Infiltrate the skin and subcutaneous tissue with local anaesthetic.

The point of needle insertion is immediately below and to the left of the xiphisternum, between the xiphisternum and the left costal margin. Infiltrate the skin and subcutaneous tissue with local anaesthetic. Using a 10-mL syringe, advance the needle at 35° to the patient, beneath the costal margin and towards the left shoulder, aspirating continuously and observing the ECG (Fig. 15.6).

Using a 10-mL syringe, advance the needle at 35° to the patient, beneath the costal margin and towards the left shoulder, aspirating continuously and observing the ECG (Fig. 15.6). Fluid (straw-coloured effusion or blood) is generally aspirated at a depth of 6–8 cm.Hold the needle stationary and pass the guide wire through the needle into the pericardial space.

Fluid (straw-coloured effusion or blood) is generally aspirated at a depth of 6–8 cm.Hold the needle stationary and pass the guide wire through the needle into the pericardial space. Remove the needle, leaving the guide wire in situ and then pass the catheter over the wire into the pericardial space. Attach a three-way tap.

Remove the needle, leaving the guide wire in situ and then pass the catheter over the wire into the pericardial space. Attach a three-way tap. Use a 50-mL syringe to aspirate pericardial effusion or attach to a closed drainage system such as a vacuum bottle. Aspiration should produce immediate haemodynamic improvement.

Use a 50-mL syringe to aspirate pericardial effusion or attach to a closed drainage system such as a vacuum bottle. Aspiration should produce immediate haemodynamic improvement.DEFIBRILLATION AND DC CARDIOVERSION

Elective cardioversion is beyond the scope of this book. Life-threatening ‘shockable rhythm’ should be managed according to advanced life support protocols. (See pp. 90–98.) For cardioversion in the emergency situation, i.e. the intensive care patient with haemodynamic compromise, the following approach is reasonable.

Procedure

Pericardial aspiration. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

10-mL syringe of local anaesthetic and needle

Ensure the patient is adequately sedated / anaesthetized. This may require supplementation of existing sedation / analgesia with a small bolus dose of midazolam, opioid or other similar agent. Conscious patients will require anaesthesia, usually with a cardiostable drug (e.g. etomidate) or volatile agent Seek anaesthetic support.

Ensure the patient is adequately sedated / anaesthetized. This may require supplementation of existing sedation / analgesia with a small bolus dose of midazolam, opioid or other similar agent. Conscious patients will require anaesthesia, usually with a cardiostable drug (e.g. etomidate) or volatile agent Seek anaesthetic support. Select the appropriate mode (asynchronous or synchronous) and select required energy levels (see relevant algorithms) before removing the paddles from the defibrillator.

Select the appropriate mode (asynchronous or synchronous) and select required energy levels (see relevant algorithms) before removing the paddles from the defibrillator. Take paddles from the defibrillator and place immediately on to gel pads on the patient. Only charge the paddles once they are in contact with the patient.

Take paddles from the defibrillator and place immediately on to gel pads on the patient. Only charge the paddles once they are in contact with the patient. Before charging paddles give an ‘all clear’ warning to ensure that no-one is touching the patient and check that everyone is clear.

Before charging paddles give an ‘all clear’ warning to ensure that no-one is touching the patient and check that everyone is clear. Before delivering the shock, give a second all clear warning; check that everyone is clear and that any oxygen source is temporarily removed from the patient. Ensure that you yourself are not inadvertently in contact with the patient.

Before delivering the shock, give a second all clear warning; check that everyone is clear and that any oxygen source is temporarily removed from the patient. Ensure that you yourself are not inadvertently in contact with the patient. After delivery of the shock, several seconds may pass before monitors yield an ECG trace. Keep paddles in contact with the patient if you may wish to deliver a further shock, or return them to the safe position on the defibrillator.

After delivery of the shock, several seconds may pass before monitors yield an ECG trace. Keep paddles in contact with the patient if you may wish to deliver a further shock, or return them to the safe position on the defibrillator.If normal rhythm is not restored seek expert help. Consider:

INTUBATION OF THE TRACHEA

Indications

These fall broadly into three groups: relieving airway obstruction, protection of the airway from aspiration and facilitation of artificial ventilation of the lungs. Typical indications are given in Box 15.4.

Box 15.4 Indications for tracheal intubation

| Airway obstruction | Risks of aspiration | Facilitation of IPPV |

|---|---|---|

| Tumours | Obtunded consciousness level | Anaesthesia and surgery |

| Head and neck trauma | Bulbar palsy | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| Epiglottitis | Impaired cough reflexes | Respiratory failure |

| Surgery | Cardiac failure | |

| Airway oedema | Multisystem organ failure | |

| Major trauma including chest injury | ||

| Brain injury |

Muscle relaxants will usually be required to facilitate intubation. Suxamethonium (1–2 mg/kg) is rapid in onset and relatively short-acting in most patients. It is the drug of choice for rapid sequence induction. It has a number of side-effects, however, which limit its use. Atracurium (0.5 mg/kg) is an alternative, but is slower in onset and has a longer duration of action.

Procedure

Tracheal intubation. You will need:

Self-inflating bag (Ambu or similar) and oxygen supply

Two laryngoscopes (check bulbs)

Selection of endotracheal tubes

Syringe for cuff inflation and tape to tie tube

Gum-elastic bougie, airway exchange catheter or rigid stilette

Laryngeal mask (for use in failed intubation) sizes 3, 4, 5.

Preoxygenate the patient. Administer 100% oxygen using a tight-fitting face mask for a period of 3–4 min prior to administering any drugs or attempting intubation, if possible. This will wash out nitrogen and fill the functional residual capacity with oxygen, thereby providing an oxygen reservoir and increasing the safety margin in the event of difficulties.

Preoxygenate the patient. Administer 100% oxygen using a tight-fitting face mask for a period of 3–4 min prior to administering any drugs or attempting intubation, if possible. This will wash out nitrogen and fill the functional residual capacity with oxygen, thereby providing an oxygen reservoir and increasing the safety margin in the event of difficulties. Check the head is in the ‘sniffing the morning air’ position (neck flexed, atlantoaxial joint extended, one firm pillow).

Check the head is in the ‘sniffing the morning air’ position (neck flexed, atlantoaxial joint extended, one firm pillow). If the patient might have a full stomach, ask your assistant to apply cricoid pressure; if the neck is supported from behind and the cricoid firmly gripped, downward pressure prevents any passive regurgitation. If possible, avoid inflating the lungs with the face mask and self-inflating bag until the tube is in place, as blowing air into the stomach may increase the risks of regurgitation.

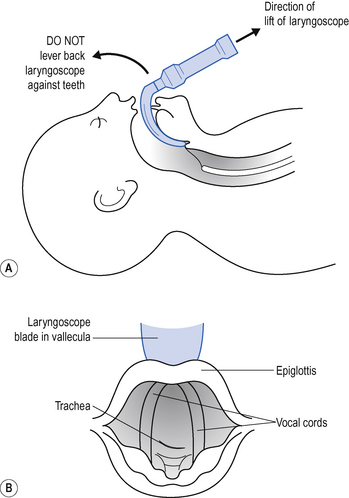

If the patient might have a full stomach, ask your assistant to apply cricoid pressure; if the neck is supported from behind and the cricoid firmly gripped, downward pressure prevents any passive regurgitation. If possible, avoid inflating the lungs with the face mask and self-inflating bag until the tube is in place, as blowing air into the stomach may increase the risks of regurgitation. Hold the laryngoscope in the left hand (size 3 or 4 Macintosh scopes are most commonly used). Slide the scope into the right of the mouth, sweeping the tongue into the groove in the blade, under it and to the left. As you advance the laryngoscope blade over the base of the tongue, the epiglottis pops into sight. With the blade between the epiglottis and the base of the tongue (vallecula), apply traction in the line of the laryngoscope handle, gently drawing the epiglottis forward and exposing the V-shaped glottis behind (Fig. 15.7).

Hold the laryngoscope in the left hand (size 3 or 4 Macintosh scopes are most commonly used). Slide the scope into the right of the mouth, sweeping the tongue into the groove in the blade, under it and to the left. As you advance the laryngoscope blade over the base of the tongue, the epiglottis pops into sight. With the blade between the epiglottis and the base of the tongue (vallecula), apply traction in the line of the laryngoscope handle, gently drawing the epiglottis forward and exposing the V-shaped glottis behind (Fig. 15.7). Pass the endotracheal tube between the vocal cords so that the cuff is just distal to them. There is usually a mark on the endotracheal tube above the cuff, which when placed at the level of the cords indicates the correct position of the tube.

Pass the endotracheal tube between the vocal cords so that the cuff is just distal to them. There is usually a mark on the endotracheal tube above the cuff, which when placed at the level of the cords indicates the correct position of the tube. If you can visualize the vocal cords but are having difficulty passing the endotracheal tube into the larynx, pass a gum elastic bougie or airway exchange catheter into the larynx and then try passing a lubricated endotracheal tube over this.

If you can visualize the vocal cords but are having difficulty passing the endotracheal tube into the larynx, pass a gum elastic bougie or airway exchange catheter into the larynx and then try passing a lubricated endotracheal tube over this. Inflate the cuff while ventilating through the endotracheal tube with the self-inflating bag until any gas leak just disappears.

Inflate the cuff while ventilating through the endotracheal tube with the self-inflating bag until any gas leak just disappears. Verify correct positioning of the tube by observation of chest movement, auscultation and capnography. Secure it, and attach to the ventilator via a suitable catheter mount. Recheck the tube position and chest movement.

Verify correct positioning of the tube by observation of chest movement, auscultation and capnography. Secure it, and attach to the ventilator via a suitable catheter mount. Recheck the tube position and chest movement. Check the cuff pressure with a standard pressure gauge to reduce the risks of laryngeal mucosal injury.

Check the cuff pressure with a standard pressure gauge to reduce the risks of laryngeal mucosal injury.Complications

Potential complications of endotracheal intubation are shown in Box 15.5.

| Immediate | Late |

|---|---|

| Hypoxia (prolonged attempts) | Accidental extubation or obstruction of airway |

| Misplacement of tube | Complications associated with mechanical ventilation |

| Obstruction of airway | Ventilator associated pneumonia |

| Aspiration | Sinusitis |

| Trauma to teeth | Injury to vocal cords |

| Trauma to airway / larynx / trachea | Tracheal stenosis |

Nasal intubation may provoke epistaxis or predispose to mucosal injury (e.g. submucosal positioning of the tube). In the longer term, nasal intubation may occlude the maxillary antrum and give rise to sinusitis. It is nevertheless better tolerated than oral intubation, particularly during weaning from ventilation. Long-term complications include erosion and stenosis of local tissues, particularly of the larynx and trachea. This may present as airway obstruction and stridor after extubation (see p. 138).

EXTUBATION OF THE TRACHEA

Check a suitable system for providing humidified oxygen by face mask is available, and that you have everything necessary for reintubation.

Check a suitable system for providing humidified oxygen by face mask is available, and that you have everything necessary for reintubation. Explain to the patient what you are going to do, then aspirate any secretions from the posterior pharynx.

Explain to the patient what you are going to do, then aspirate any secretions from the posterior pharynx.INSERTION OF LARYNGEAL MASK (SUPRAGLOTTIC AIRWAYS)

PERCUTANEOUS TRACHEOSTOMY

Potential advantages of tracheostomy

More comfortable than naso- / orotracheal tubes, which allows significant reductions in muscle relaxants, sedative and analgesic drugs. This promotes return of GI tract function.

More comfortable than naso- / orotracheal tubes, which allows significant reductions in muscle relaxants, sedative and analgesic drugs. This promotes return of GI tract function. Patients easily switched from IPPV / assist modes / CPAP / T-piece without the need for extubation and reintubation.

Patients easily switched from IPPV / assist modes / CPAP / T-piece without the need for extubation and reintubation.Indications

Procedure

Percutaneous tracheostomy. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

Local anaesthetic (1% lidocaine (lignocaine) + adrenaline (epinephrine), syringe and needle

10 mL normal saline and syringe

Basic surgical instruments (e.g. venous cut down set)

Appropriate size cuffed tracheostomy tubes (1 size smaller and larger than planned)

Anaesthetist

Ensure appropriate monitoring and anaesthetize patient with inhalational or intravenous technique as appropriate. Beware of relying solely on intermittent bolus of propofol, as there is a risk of ‘awareness’. A muscle relaxant is usually required.

Ensure appropriate monitoring and anaesthetize patient with inhalational or intravenous technique as appropriate. Beware of relying solely on intermittent bolus of propofol, as there is a risk of ‘awareness’. A muscle relaxant is usually required. When the operator is ready, withdraw the endotracheal tube under direct vision using a laryngoscope, until the cuff is visible at the laryngeal inlet. This prevents the endotracheal tube being transfixed by the operator’s needle when the trachea is punctured.

When the operator is ready, withdraw the endotracheal tube under direct vision using a laryngoscope, until the cuff is visible at the laryngeal inlet. This prevents the endotracheal tube being transfixed by the operator’s needle when the trachea is punctured. Care must be taken not to lose the airway when the tube is withdrawn. Consider passing a gum elastic bougie or airway exchange catheter down the tube prior to withdrawal, to ensure the tube can be replaced if it is pulled back too far. (Equipment must be available to reintubate the patient in case of difficulty.)

Care must be taken not to lose the airway when the tube is withdrawn. Consider passing a gum elastic bougie or airway exchange catheter down the tube prior to withdrawal, to ensure the tube can be replaced if it is pulled back too far. (Equipment must be available to reintubate the patient in case of difficulty.) An alternative approach is to remove the endotracheal tube altogether and to use a laryngeal mask to maintain ventilation and oxygenation.

An alternative approach is to remove the endotracheal tube altogether and to use a laryngeal mask to maintain ventilation and oxygenation.Operator

Examine the neck and ascertain the position of the trachea. Look for anatomical abnormalities, large veins or palpable arterial pulsation. (Ultrasound gives good images of deeper vessels that may be at risk during the procedure.)

Examine the neck and ascertain the position of the trachea. Look for anatomical abnormalities, large veins or palpable arterial pulsation. (Ultrasound gives good images of deeper vessels that may be at risk during the procedure.) Palpate the cricothyroid membrane and sternal notch. Infiltrate the skin with 1% lidocaine (lignocaine) and adrenaline (epinephrine), midway between the two.

Palpate the cricothyroid membrane and sternal notch. Infiltrate the skin with 1% lidocaine (lignocaine) and adrenaline (epinephrine), midway between the two. Use blunt forceps and a finger to dissect the pretracheal tissue until you can feel the tracheal rings and identify the level. If necessary, tie off the anterior jugular veins, which occasionally bleed.

Use blunt forceps and a finger to dissect the pretracheal tissue until you can feel the tracheal rings and identify the level. If necessary, tie off the anterior jugular veins, which occasionally bleed. Puncture the trachea with the introducer needle below the level of the first tracheal ring and in the midline. Using a saline-filled syringe, confirm the position of the needle by aspiration of air/mucus from the trachea. A bronchoscope passed through the endotracheal tube can also be used to confirm the correct position of the needle tip within the tracheal lumen. A green seeker needle may be helpful if difficulties are encountered in cannulating the trachea.

Puncture the trachea with the introducer needle below the level of the first tracheal ring and in the midline. Using a saline-filled syringe, confirm the position of the needle by aspiration of air/mucus from the trachea. A bronchoscope passed through the endotracheal tube can also be used to confirm the correct position of the needle tip within the tracheal lumen. A green seeker needle may be helpful if difficulties are encountered in cannulating the trachea. Dilate the trachea according to the manufacturer’s instructions supplied with the tracheostomy kit used and insert the tracheostomy tube, again according to instructions.

Dilate the trachea according to the manufacturer’s instructions supplied with the tracheostomy kit used and insert the tracheostomy tube, again according to instructions. Suck out any blood from the trachea. Blood clot in the airway may produce total airway obstruction or act as a ball valve, allowing gas in but not out.

Suck out any blood from the trachea. Blood clot in the airway may produce total airway obstruction or act as a ball valve, allowing gas in but not out. Correct placement of the tube may be confirmed by bronchoscopy or capnography. (Bronchoscopy has the advantage of being able to confirm the position of the tracheal tube in relation to the carina.)

Correct placement of the tube may be confirmed by bronchoscopy or capnography. (Bronchoscopy has the advantage of being able to confirm the position of the tracheal tube in relation to the carina.) Check that chest expansion is symmetrical and that there are bilateral breath sounds, and that oxygen saturations are maintained.

Check that chest expansion is symmetrical and that there are bilateral breath sounds, and that oxygen saturations are maintained.COMMON PROBLEMS DURING PERCUTANEOUS TRACHEOSTOMY

Difficulty ventilating the patient

This usually means that the tracheostomy tube has been misplaced. Do not persist as this may produce a tension pneumothorax! Remove the tracheostomy tube and reintubate the patient by the oral route.

Complications

The potential complications of percutaneous tracheostomy are shown in Box 15.6.

Box 15.6 Complications of tracheostomy

| Early | Late |

|---|---|

| Bleeding (may lead to total airway obstruction) | Tracheal stenosis |

| Pneumothorax | Tracheo–oesophageal fistula |

| Tube misplacement or dislodgement | Skin tethering / scarring |

| Air emphysema | Late haemorrhage from innominate vessels |

| Mucus plugging / obstruction | |

| Stomal infection |

Changing tracheostomy tubes

Tracheostomy tubes can be changed at any time if necessary, but it is more difficult if the tract is not well established. Administer 100% oxygen and position as for performing a tracheostomy. Pass a large-bore suction catheter (with the end cut off) or gum elastic bougie through the old tracheostomy tube before removing it and use this as a guide to insert the new tube. Facilities for ventilating the patient with a bag and mask and for reintubation should be available in case of difficulty.

CRICOTHYROIDOTOMY/MINITRACHEOSTOMY

Minitracheostomy is a term used to describe the insertion of a similar small-bore non-cuffed tube through the cricothyroid membrane (4 mm internal diameter), principally to aid the clearance of secretions. The passage of suction catheters stimulates coughing and allows secretions to be aspirated. As a short-term measure these devices may help to prevent the need for naso-/orotracheal intubation and assisted ventilation. The small size of the tube limits its value and the use of minitracheostomy has declined in recent years.

Procedure

Cricothyroidotomy / minitracheostomy. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

Cricothyroidotomy / minitracheostomy kit (containing needle, guide wire, dilator tube and tape)

Warn the patient that you are going to make him or her cough and perform cricothyroid puncture with a green 21-gauge needle. Aspirate air to confirm the tracheal position of the needle and rapidly inject 2 mL of lidocaine (lignocaine). Wait for coughing to subside.

Warn the patient that you are going to make him or her cough and perform cricothyroid puncture with a green 21-gauge needle. Aspirate air to confirm the tracheal position of the needle and rapidly inject 2 mL of lidocaine (lignocaine). Wait for coughing to subside.FIBREOPTIC BRONCHOSCOPY

Procedure

Adequately sedate the patient and then give a small dose of muscle relaxant (such as atracurium) to prevent the patient biting or coughing on the bronchoscope. Instil 3–5 mL of local anaesthetic (e.g. 1% lidocaine (lignocaine)) down the trachea. It is sensible to have an assistant to look after patient sedation and ventilation while you perform the bronchoscopy.

Adequately sedate the patient and then give a small dose of muscle relaxant (such as atracurium) to prevent the patient biting or coughing on the bronchoscope. Instil 3–5 mL of local anaesthetic (e.g. 1% lidocaine (lignocaine)) down the trachea. It is sensible to have an assistant to look after patient sedation and ventilation while you perform the bronchoscopy. Pass the bronchoscope through the bung on the swivel connector and into the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube. Continue forward under direct vision.

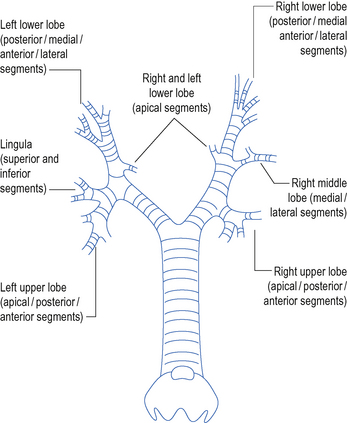

Pass the bronchoscope through the bung on the swivel connector and into the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube. Continue forward under direct vision. Pass the scope forward to the carina. Then explore each side of the bronchial tree in turn. Identify and enter each lobar and segmental bronchus (Fig. 15.8). Take note of any abnormal anatomy and remove any secretions.

Pass the scope forward to the carina. Then explore each side of the bronchial tree in turn. Identify and enter each lobar and segmental bronchus (Fig. 15.8). Take note of any abnormal anatomy and remove any secretions. If there are thick secretions that cannot be sucked up the scope, try instilling 10–20 mL of sterile saline down the suction port of the bronchoscope. This may help to loosen them. Large plugs and blood clots may be dragged out on the end of the scope.

If there are thick secretions that cannot be sucked up the scope, try instilling 10–20 mL of sterile saline down the suction port of the bronchoscope. This may help to loosen them. Large plugs and blood clots may be dragged out on the end of the scope. To obtain microbiology specimens place a sputum trap in between the bronchoscope and the wall suction. Use a separate trap for each side. Be careful to keep the sputum trap upright to prevent the secretions disappearing down the suction tubing. Also remove sputum traps before removing the scope from the patient to prevent specimens being contaminated with upper airway flora.

To obtain microbiology specimens place a sputum trap in between the bronchoscope and the wall suction. Use a separate trap for each side. Be careful to keep the sputum trap upright to prevent the secretions disappearing down the suction tubing. Also remove sputum traps before removing the scope from the patient to prevent specimens being contaminated with upper airway flora. Trainees in intensive care should not perform bronchial biopsy. If you see a suspicious lesion that you think is a tumour or something else, leave it. Call for help to ascertain how to diagnose/manage the problem. Note that clotted blood over time becomes white and can mimic tumour appearances to the uninitiated.

Trainees in intensive care should not perform bronchial biopsy. If you see a suspicious lesion that you think is a tumour or something else, leave it. Call for help to ascertain how to diagnose/manage the problem. Note that clotted blood over time becomes white and can mimic tumour appearances to the uninitiated.BRONCHOALVEOLAR LAVAGE

BAL using catheter

Advance the inner protected suction catheter forwards until it meets resistance. Do not use undue force.

Advance the inner protected suction catheter forwards until it meets resistance. Do not use undue force. Perform BAL according to local protocol. Generally 80–100 mL of saline are instilled down the suction catheter, and then aspirated into two or three sputum traps. Not all the saline may be aspirated. This does not matter, it will be absorbed.

Perform BAL according to local protocol. Generally 80–100 mL of saline are instilled down the suction catheter, and then aspirated into two or three sputum traps. Not all the saline may be aspirated. This does not matter, it will be absorbed.Having performed a BAL, telephone the laboratory and then send samples immediately with full diagnostic information and appropriate requests (Box 15.7).

INSERTION OF CHEST DRAIN

The emergency treatment of life-threatening tension pneumothorax is large-bore needle decompression. The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds without chest X-ray. (Hyper-resonance, reduced breath sounds, deviated trachea, haemodynamic compromise.) A 14-gauge cannula is inserted into the pleural cavity immediately above the second rib in the midclavicular line to allow air under tension in the pleural space to escape. This should always be followed by placement of a formal chest drain.

Site of drain

This is partly dictated by the position of the collection clinically and radiographically. In the case of long-standing collections, which may be loculated, ultrasound guidance may be helpful. In all other cases the drain should be sited in the 5th intercostal space, just anterior to the midaxillary line, and can be directed cephalad for air and caudally for fluid or blood. All drains should be placed immediately above the rib to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundle, which lies underneath.

Procedure

Chest drainage. You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

10-mL syringe, local anaesthetic and needles (lidocaine (lignocaine) 1–2%)

Basic instruments: scalpel, blade, large arterial clamps

Insertion of drain through thoracostomy

COMMON PROBLEMS DURING INSERTION OF CHEST DRAINS

Persistent air leak

Indications for urgent thoracic surgical opinion

The combination of persistent air leak and non-compliant lungs (e.g. ARDS) may make adequate ventilation and gas exchange impossible. Urgent thoracic surgical opinion may be required (Box 15.8).

PASSING A NASOGASTRIC TUBE

Most patients in the ICU who require ventilation require a nasogastric tube, initially at least, to ensure gastric drainage and early enteral feeding (Box 15.9).

Box 15.9 Indications and contraindications for nasogastric tube

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| To deflate the stomach after bag mask ventilation | Base of skull fracture (use orogastric tube) |

| To aspirate gastric contents which might otherwise reflux and soil the airway | Recent gastric or oesophageal surgery (discuss with surgeon) |

| To provide a route for enteral feeding and drugs | Oesophageal varices (relative contraindication) |

| Severe coagulopathy (consider oral route to avoid nose bleed) |

Procedure

Lubricate the NG tube and, keeping alignment with the long axis of the patient, introduce through the nose. Do not force. If resistance is met, try the other side.

Lubricate the NG tube and, keeping alignment with the long axis of the patient, introduce through the nose. Do not force. If resistance is met, try the other side. If the patient is cooperative, ask them to swallow the tip of the tube when they feel it in the back of the throat. In unconscious patients the tube may pass directly into the oesophagus but often coils up in the mouth.

If the patient is cooperative, ask them to swallow the tip of the tube when they feel it in the back of the throat. In unconscious patients the tube may pass directly into the oesophagus but often coils up in the mouth. In this case, use a laryngoscope to examine the pharynx and pass the tube manually into the oesophagus using a pair of Magill forceps. (Be careful not to traumatize the uvula and pharyngeal mucosa.)

In this case, use a laryngoscope to examine the pharynx and pass the tube manually into the oesophagus using a pair of Magill forceps. (Be careful not to traumatize the uvula and pharyngeal mucosa.) Confirm the position of the NG tube in the stomach by aspiration of gastric contents (turns litmus paper red). Position below the diaphragm should be subsequently verified on chest X-ray.

Confirm the position of the NG tube in the stomach by aspiration of gastric contents (turns litmus paper red). Position below the diaphragm should be subsequently verified on chest X-ray.PASSING A SENGSTAKEN–BLAKEMORE TUBE

A number of tubes have been designed to apply pressure to oesophageal varices in order to compress the vessels and reduce bleeding while the patient is resuscitated and definitive treatment carried out. The Sengstaken–Blakemore tube has three lumens. Two are used to inflate balloons, one in the stomach and the other in the oesophagus, while the third is used to aspirate gastric contents.

Procedure

Passing a Sengstaken–Blakemore tube. You will need:

Pass the tube orally into the oesophagus and down into the stomach. (Local anaesthetic spray to the pharynx may make this more tolerable in the awake patient.) Insert the tube to at least 35 cm (>55 cm may enter the duodenum).

Pass the tube orally into the oesophagus and down into the stomach. (Local anaesthetic spray to the pharynx may make this more tolerable in the awake patient.) Insert the tube to at least 35 cm (>55 cm may enter the duodenum). Pull the tube backwards gently until resistance is felt as the gastric balloon meets the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Pull the tube backwards gently until resistance is felt as the gastric balloon meets the gastro-oesophageal junction. Inflate the oesophageal balloon with air or saline (approximately 100 mL). The pressure in the oesophageal balloon can be measured using a sphygmomanometer and should be 25–35 mmHg. Chest pain, respiratory difficulty and cardiac arrhythmias may occur during inflation of the balloon.

Inflate the oesophageal balloon with air or saline (approximately 100 mL). The pressure in the oesophageal balloon can be measured using a sphygmomanometer and should be 25–35 mmHg. Chest pain, respiratory difficulty and cardiac arrhythmias may occur during inflation of the balloon. Apply traction to the tube by tying a piece of string to the end and suspending a 500 mL bag of fluid over a fulcrum. Traction should be released at regular intervals to prevent pressure necrosis of the gastro–oesophageal junction.

Apply traction to the tube by tying a piece of string to the end and suspending a 500 mL bag of fluid over a fulcrum. Traction should be released at regular intervals to prevent pressure necrosis of the gastro–oesophageal junction.PERITONEAL TAP/DRAINAGE OF ASCITES

Drainage of ascites: You will need:

Universal precautions; sterile gown and gloves

10-mL syringe, local anaesthetic lidocaine (lignocaine) 1–2% and needles

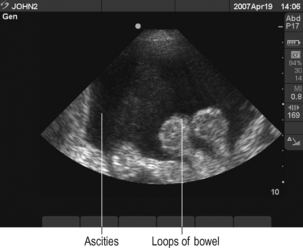

Before commencing procedure perform ultrasound to demonstrate fluid and verify position for needle puncture away from bowel (Fig. 15.9).

Before commencing procedure perform ultrasound to demonstrate fluid and verify position for needle puncture away from bowel (Fig. 15.9).There is debate about how much fluid should be drained and what replacement fluid should be used. Seek local guidance.

TURNING A PATIENT PRONE

Ensure that all lines and monitoring cables are positioned such that they will not be trapped under the patient when he or she is turned.

Ensure that all lines and monitoring cables are positioned such that they will not be trapped under the patient when he or she is turned. Designate specific individuals to be responsible for maintaining the security of the endotracheal tube, vascular access and lines. Designate other individuals to turn the patient.

Designate specific individuals to be responsible for maintaining the security of the endotracheal tube, vascular access and lines. Designate other individuals to turn the patient. Position pillows so that they will be under the patient’s chest and pelvis when the patient is prone. Alternatively, position them afterwards. They are to ensure that the abdomen is not compressed, which can impair venous return and CO.

Position pillows so that they will be under the patient’s chest and pelvis when the patient is prone. Alternatively, position them afterwards. They are to ensure that the abdomen is not compressed, which can impair venous return and CO.TRANSPORT OF CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS

Full monitoring should be continued. This should include blood pressure monitoring (preferably invasive), ECG, oxygen saturation, and end-tidal CO2 for intubated / ventilated patients. If a PA catheter is in situ the pressure trace must be displayed, or the catheter should be pulled back into the SVC to prevent inadvertent pulmonary artery occlusion.

Full monitoring should be continued. This should include blood pressure monitoring (preferably invasive), ECG, oxygen saturation, and end-tidal CO2 for intubated / ventilated patients. If a PA catheter is in situ the pressure trace must be displayed, or the catheter should be pulled back into the SVC to prevent inadvertent pulmonary artery occlusion. Ensure adequate supplies of oxygen to complete the transfer. In case the supply fails, an alternative means of ventilating the patient should be available. This should be a self-inflating bag, rather than an anaesthetic breathing circuit.

Ensure adequate supplies of oxygen to complete the transfer. In case the supply fails, an alternative means of ventilating the patient should be available. This should be a self-inflating bag, rather than an anaesthetic breathing circuit. Discontinue non-essential drug infusions. Ensure that essential infusions are delivered using syringe pumps with fully charged batteries.

Discontinue non-essential drug infusions. Ensure that essential infusions are delivered using syringe pumps with fully charged batteries.

Always seek senior help if you are not familiar with a procedure.

Always seek senior help if you are not familiar with a procedure.

If you do accidentally cut, scrape or puncture your skin, follow the ‘accidental inoculation procedure’, encourage bleeding, wash with warm soapy water, dry and cover with a waterproof dressing. Report the incident to the senior person in charge and ensure a report is completed. Seek advice from the occupational health department or A&E. In some cases, post-exposure prophylaxis may be required. This is time-critical, so seek immediate advice. It may be appropriate for someone else to complete the practical procedure.

If you do accidentally cut, scrape or puncture your skin, follow the ‘accidental inoculation procedure’, encourage bleeding, wash with warm soapy water, dry and cover with a waterproof dressing. Report the incident to the senior person in charge and ensure a report is completed. Seek advice from the occupational health department or A&E. In some cases, post-exposure prophylaxis may be required. This is time-critical, so seek immediate advice. It may be appropriate for someone else to complete the practical procedure.

Do not attempt central venous cannulation without supervision until you have been adequately taught to do so. You must be aware of possible complications and how to manage them.

Do not attempt central venous cannulation without supervision until you have been adequately taught to do so. You must be aware of possible complications and how to manage them.

Effective use of ultrasound requires practice. In particular the needle must be visualized as it passes into the vessel. Seek instruction before attempting to use it on a patient.

Effective use of ultrasound requires practice. In particular the needle must be visualized as it passes into the vessel. Seek instruction before attempting to use it on a patient.

It is a common mistake to assume the internal jugular vein is deep. Typically it is <2 cm from the skin. Do not introduce the needle to its full length. There is a danger of puncturing the apex of the lung.

It is a common mistake to assume the internal jugular vein is deep. Typically it is <2 cm from the skin. Do not introduce the needle to its full length. There is a danger of puncturing the apex of the lung.

If you appear to have missed the vein on the first pass, pull back slowly while maintaining suction on the syringe. You often find you have gone through the vein and can identify it on withdrawal.

If you appear to have missed the vein on the first pass, pull back slowly while maintaining suction on the syringe. You often find you have gone through the vein and can identify it on withdrawal.

Do not proceed immediately to attempt cannulation on the contralateral side: this increases the risk of complications, such as bilateral pneumothorax!

Do not proceed immediately to attempt cannulation on the contralateral side: this increases the risk of complications, such as bilateral pneumothorax!

The difficulty with this technique is retaining sterility, Wear two pairs of gloves and discard the top pair when you have removed the old line.

The difficulty with this technique is retaining sterility, Wear two pairs of gloves and discard the top pair when you have removed the old line.

The dilators provided are often very stiff and can easily kink guide wires and tear vessels if advanced too far or too aggressively. If difficulties are encountered in inserting dilators, abandon the procedure and call for help. If possible avoid left internal jugular routes.

The dilators provided are often very stiff and can easily kink guide wires and tear vessels if advanced too far or too aggressively. If difficulties are encountered in inserting dilators, abandon the procedure and call for help. If possible avoid left internal jugular routes. Before attempting to insert a PA catheter, ECG monitoring must be established and a defibrillator must be immediately available because of the risks of dysrhythmia.

Before attempting to insert a PA catheter, ECG monitoring must be established and a defibrillator must be immediately available because of the risks of dysrhythmia.

Never advance the catheter with the balloon down. Never pass more than 20 cm of catheter without seeing a change in the trace. Never pull the catheter back with the balloon up.

Never advance the catheter with the balloon down. Never pass more than 20 cm of catheter without seeing a change in the trace. Never pull the catheter back with the balloon up.

Best results are obtained using ice-cold (<4°C) 5% dextrose for the injectate. For convenience, however, room temperature injectate may be used. Ensure the correct computation constant is entered for the temperature of injectate used.

Best results are obtained using ice-cold (<4°C) 5% dextrose for the injectate. For convenience, however, room temperature injectate may be used. Ensure the correct computation constant is entered for the temperature of injectate used.

In an emergency situation when aspirating presumed cardiac tamponade it is difficult to know whether blood aspirated is from the pericardial space or whether the ventricle has been punctured. Observe the ECG throughout. If the needle touches the ventricle, an injury pattern or arrhythmia should be observed.

In an emergency situation when aspirating presumed cardiac tamponade it is difficult to know whether blood aspirated is from the pericardial space or whether the ventricle has been punctured. Observe the ECG throughout. If the needle touches the ventricle, an injury pattern or arrhythmia should be observed. Defibrillators are potentially dangerous pieces of equipment. Make sure you know how to use defibrillator equipment safely. It is your responsibility to ensure the safety of everyone in the proximity, including yourself. Paddles should be either on the defibrillator (safe position) or in contact with the patient. Do not charge except when ready to deliver a shock.

Defibrillators are potentially dangerous pieces of equipment. Make sure you know how to use defibrillator equipment safely. It is your responsibility to ensure the safety of everyone in the proximity, including yourself. Paddles should be either on the defibrillator (safe position) or in contact with the patient. Do not charge except when ready to deliver a shock.

Do not attempt tracheal intubation without senior help if you are not experienced in the technique. In an emergency, ventilate the patient with a bag and mask or via a laryngeal mask and await reinforcements!

Do not attempt tracheal intubation without senior help if you are not experienced in the technique. In an emergency, ventilate the patient with a bag and mask or via a laryngeal mask and await reinforcements! Do not use i.v. anaesthetic agents or muscle relaxants unless you are familiar with them. Seek senior help. (See Sedation and analgesia, p. 34, Muscle relaxants, p. 43 and Contraindications to suxamethonium, p. 43.)

Do not use i.v. anaesthetic agents or muscle relaxants unless you are familiar with them. Seek senior help. (See Sedation and analgesia, p. 34, Muscle relaxants, p. 43 and Contraindications to suxamethonium, p. 43.) If immediate intubation proves to be difficult or impracticable, do not persist with fruitless attempts. Ventilate the patient with 100% oxygen using bag and mask or laryngeal mask and call for help.

If immediate intubation proves to be difficult or impracticable, do not persist with fruitless attempts. Ventilate the patient with 100% oxygen using bag and mask or laryngeal mask and call for help.

This procedure requires a separate anaesthetist to manage the patient and airway and an operator to perform the tracheostomy. On no account should percutaneous tracheostomy be attempted by a single operator.

This procedure requires a separate anaesthetist to manage the patient and airway and an operator to perform the tracheostomy. On no account should percutaneous tracheostomy be attempted by a single operator.

Use of the bronchoscope clearly requires knowledge of the endoscopic anatomy of the bronchial tree. If you do not know this you should not be performing a bronchoscopy.

Use of the bronchoscope clearly requires knowledge of the endoscopic anatomy of the bronchial tree. If you do not know this you should not be performing a bronchoscopy. When handling the scope never allow it to bend or fold at an acute angle, as this will break the fibreoptic components.

When handling the scope never allow it to bend or fold at an acute angle, as this will break the fibreoptic components.

Not all the saline instilled will be aspirated back. This does not matter. If necessary repeat the procedure until an adequate. volume specimen is obtained.

Not all the saline instilled will be aspirated back. This does not matter. If necessary repeat the procedure until an adequate. volume specimen is obtained.

Do not attempt ‘blind’ needle decompression unless there is clear evidence of life threatening tension pneumothorax. Insertion of a needle in other circumstances is likely to create a problem where one may not have existed before.

Do not attempt ‘blind’ needle decompression unless there is clear evidence of life threatening tension pneumothorax. Insertion of a needle in other circumstances is likely to create a problem where one may not have existed before. Use of the 2nd intercostal space in the midclavicular line (anterior approach) is associated with risk of injury to the internal mammary artery and breast tissue (in the female) and may result in unsightly scarring. Do not use this approach.

Use of the 2nd intercostal space in the midclavicular line (anterior approach) is associated with risk of injury to the internal mammary artery and breast tissue (in the female) and may result in unsightly scarring. Do not use this approach. Do not use trocars to insert drains. They are sharp and may cause injury to underlying viscera.

Do not use trocars to insert drains. They are sharp and may cause injury to underlying viscera.

DO NOT CLAMP CHEST DRAINS. If moving a patient, simply keep the underwater drain bottle below the level of the chest. Clamping drains may produce a tension pneumothorax.

DO NOT CLAMP CHEST DRAINS. If moving a patient, simply keep the underwater drain bottle below the level of the chest. Clamping drains may produce a tension pneumothorax.

When assessing a chest drain on X-ray, look at the length of the tube and whether it is kinked or needs to be pulled back or has slipped out. Check the position of the drainage holes – are they within the chest. The limitations of an AP chest X-ray should be appreciated. Tubes may lie within the lung parenchyma and this will only be identified on CT.

When assessing a chest drain on X-ray, look at the length of the tube and whether it is kinked or needs to be pulled back or has slipped out. Check the position of the drainage holes – are they within the chest. The limitations of an AP chest X-ray should be appreciated. Tubes may lie within the lung parenchyma and this will only be identified on CT.

Do not clamp chest drains prior to removal. If a drain is not bubbling or draining, it is not performing any useful function. Remove it and re-site it if necessary.

Do not clamp chest drains prior to removal. If a drain is not bubbling or draining, it is not performing any useful function. Remove it and re-site it if necessary.

Beware that the presence of a cuffed endotracheal or tracheostomy tube does necessarily prevent gastric tubes entering the lung. Awake patients can tolerate fine bore tubes within the lung and it should be appreciated that some nasogastric tubes only have a radio-opaque marker on the distal segment, which may be well out in the periphery of the lung.

Beware that the presence of a cuffed endotracheal or tracheostomy tube does necessarily prevent gastric tubes entering the lung. Awake patients can tolerate fine bore tubes within the lung and it should be appreciated that some nasogastric tubes only have a radio-opaque marker on the distal segment, which may be well out in the periphery of the lung.