1 What is manic depression (bipolar disorder)?

1.2 What is bipolar affective disorder?

Psychiatrists may appear to be always changing the names of the illnesses that they treat but this is not always done just to confuse the innocent! Manic depression is a term that has been used for more than a century to cover psychiatric illnesses with the fundamental symptom of a mood change. Fifty years ago the term would have been used widely to cover not only those patients who had manic episodes but also to include those who only experienced severe depression. In the 1960s it became apparent that there are major differences between those patients that experience mania and those that only suffer from depression. The differences are particularly in the course and the family history of the two types of mood illness. However, the considerable overlap has always been recognised. In order to indicate the separation, two new terms were adopted: unipolar and bipolar–unipolar depression for those patients that only experience depression and bipolar affective disorder for those that experience mania (and usually also depression). It would make logical sense to also have a unipolar mania category but in fact the unipolar manics are so similar to the bipolars that this term has not been popular (see Q 1.13).

Manic depression is an unusual illness in that a number of people have a bipolar illness that is currently undiagnosed because so far they have only suffered from depression. Even though the illness might have started with depression in the teenage years it is only when mania appears in the twenties that the diagnosis can be made. The illness affects both genders in essentially the same way.

1.3 What do you call recurrent depression with hypomania?

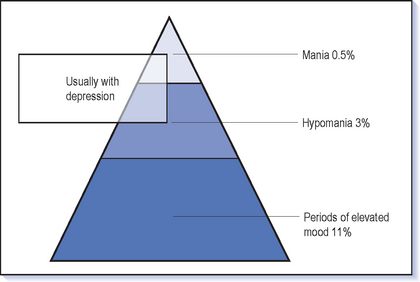

The dividing line between mania and hypomania is not easy to demarcate (see Q 1.7); however it is worthwhile making this distinction because it affects decisions about treatment (Fig. 1.1). For this reason a different name is given to depression with mania–bipolar I–in contrast to depression with hypomania–bipolar II. There have been attempts to define bipolar III and IV based on family history and the effect of antidepressants but these have not really caught on.

1.4 What are the symptoms of mania?

The following example of a manic woman illustrates the range of symptoms and behaviours characteristic of mania (see also Box 1.1).

Mood: In order to make a diagnosis of mania there must be a change in mood. This is usually elevated and she feels elated, ‘great’, ‘fantastic’. Extreme terms are used to describe a state that few of us reach. She may well be feeling ‘better than ever’, and in an exciting and unique way ‘connected with the whole world’. It is common to have never had such a good feeling in the whole of her life. One of the major problems later can be that she doesn’t feel that this is an experience that she would like to avoid; in fact she feels just the opposite because it is a feeling that one would want to seek out. The closest comparison is to feelings that a great success or achievement (or winning the lottery) can produce or the high that comes from drugs such as cocaine. The elation is often infectious and others can (at first at least) feel more cheerful in her presence and find a smile on their face. She looks happy but in an active, excited way rather than displaying a calm peaceful serenity.

Mood: In order to make a diagnosis of mania there must be a change in mood. This is usually elevated and she feels elated, ‘great’, ‘fantastic’. Extreme terms are used to describe a state that few of us reach. She may well be feeling ‘better than ever’, and in an exciting and unique way ‘connected with the whole world’. It is common to have never had such a good feeling in the whole of her life. One of the major problems later can be that she doesn’t feel that this is an experience that she would like to avoid; in fact she feels just the opposite because it is a feeling that one would want to seek out. The closest comparison is to feelings that a great success or achievement (or winning the lottery) can produce or the high that comes from drugs such as cocaine. The elation is often infectious and others can (at first at least) feel more cheerful in her presence and find a smile on their face. She looks happy but in an active, excited way rather than displaying a calm peaceful serenity.

Sleep: Sleep is reduced, but this is often not perceived as a problem but rather ‘I don’t need as much sleep as everyone else–and there is too much to do to spend all night in bed!’

Sleep: Sleep is reduced, but this is often not perceived as a problem but rather ‘I don’t need as much sleep as everyone else–and there is too much to do to spend all night in bed!’ Energy: Energy levels are high: ‘batteries fully charged and switched on’. She feels physically and mentally energised, active and strong. Overactivity is immediately apparent and she finds sitting for more than a few minutes very challenging, as well as a waste of time. She may run, dance and be constantly on the move. Increased energy also improves endurance and she may be able to walk long distances without getting tired and ignore the pain of walking barefoot.

Energy: Energy levels are high: ‘batteries fully charged and switched on’. She feels physically and mentally energised, active and strong. Overactivity is immediately apparent and she finds sitting for more than a few minutes very challenging, as well as a waste of time. She may run, dance and be constantly on the move. Increased energy also improves endurance and she may be able to walk long distances without getting tired and ignore the pain of walking barefoot. Attention span: Attention can be intense but only for a short period. Concentration is poor because of distractibility, so that she cannot spend more than a few minutes on any task before setting off on another track. Memory is perceived to be good but may actually be poor because of the distraction and lack of focus. Afterwards she may have very poor recall of the events during the spell of mania.

Attention span: Attention can be intense but only for a short period. Concentration is poor because of distractibility, so that she cannot spend more than a few minutes on any task before setting off on another track. Memory is perceived to be good but may actually be poor because of the distraction and lack of focus. Afterwards she may have very poor recall of the events during the spell of mania. Ideas and thoughts: These flow quickly, freely and fast; speech reflects this. The content is cheerful, confident and inventive until irritability and annoyance take over.

Ideas and thoughts: These flow quickly, freely and fast; speech reflects this. The content is cheerful, confident and inventive until irritability and annoyance take over. Self-belief: Overconfidence is the norm and this grows to grandiosity, claiming superior talents and achievements. Her self-belief may be very persuasive to those that don’t know her; some may go along with her plans initially, pleased to have found someone with such confidence in themselves, only to be very disappointed later. Grandiosity can become delusional with ideas of royal connections, riches, fame and natural gifts to the extent of superhuman powers (e.g. having control over the weather or ability to predict the future). Arrogance accompanies this, dismissing the views of others (unless they happen to coincide) in a haughty way. Some feel their intellectual powers are high and superior to others and start to talk in a foreign language even though their grasp of grammar and vocabulary may be limited. Physical limitations or disabilities are dismissed–‘I’ve cured myself of that diabetes’–or minimised or even perceived as signs of superiority. Mental wellbeing is reflected in a sense of physical wellbeing.

Self-belief: Overconfidence is the norm and this grows to grandiosity, claiming superior talents and achievements. Her self-belief may be very persuasive to those that don’t know her; some may go along with her plans initially, pleased to have found someone with such confidence in themselves, only to be very disappointed later. Grandiosity can become delusional with ideas of royal connections, riches, fame and natural gifts to the extent of superhuman powers (e.g. having control over the weather or ability to predict the future). Arrogance accompanies this, dismissing the views of others (unless they happen to coincide) in a haughty way. Some feel their intellectual powers are high and superior to others and start to talk in a foreign language even though their grasp of grammar and vocabulary may be limited. Physical limitations or disabilities are dismissed–‘I’ve cured myself of that diabetes’–or minimised or even perceived as signs of superiority. Mental wellbeing is reflected in a sense of physical wellbeing. Speech: She will talk non-stop and be difficult to interrupt. Staying quiet becomes impossible and dialogue is not needed–monologue is fine. In fact she does not even need an audience: you can see her wandering about, chatting away. Talking may not be enough–singing, shouting and laughter all form part of expressing her joy to the world.

Speech: She will talk non-stop and be difficult to interrupt. Staying quiet becomes impossible and dialogue is not needed–monologue is fine. In fact she does not even need an audience: you can see her wandering about, chatting away. Talking may not be enough–singing, shouting and laughter all form part of expressing her joy to the world.

Flight of ideas is the classic form of speech in mania (Box 1.2). Flight indicates the way ideas flow from one to another. The connections within the speech are usually apparent, in contrast to the thought disorder of schizophrenia which is much more obscure. But connections are too free and frequent so that distractions in what she sees or hears send her off on a new track. Alternatively, internal connections or personal memories may suddenly intervene. Playing with language is common as punning or rhyming takes over the flow for a while. The digressions mean that the goals of speech are quickly lost and so little is achieved in any conversation.

Appetite: Appetite may be little changed though she will lose weight because essentials such as eating are not given much priority, or poor concentration and distractibility leave everything half eaten.

Appetite: Appetite may be little changed though she will lose weight because essentials such as eating are not given much priority, or poor concentration and distractibility leave everything half eaten. Disinhibition: You may notice the disinhibition from a distance with flamboyant, bright, eccentric clothes and a home visit reveals a spectacularly decorated house. It is always interesting to visit a house in the summer which is decked out for Christmas because ‘I’m the second coming’. However, be wary of the conservatively dressed Englishman whose dress belies his extraordinary behaviour.

Disinhibition: You may notice the disinhibition from a distance with flamboyant, bright, eccentric clothes and a home visit reveals a spectacularly decorated house. It is always interesting to visit a house in the summer which is decked out for Christmas because ‘I’m the second coming’. However, be wary of the conservatively dressed Englishman whose dress belies his extraordinary behaviour.

Later stages: The fun of mania rarely lasts long and the initial infectious cheerfulness degenerates into unstoppable destructive irresponsibility. Others trying to bring her back to earth are dismissed, abused and ignored as the bank account gets emptied and exploiters strip her of her assets and dignity. Her ideas become obviously farcical and she becomes a figure of pity if not ridicule. Finally, someone takes action to get her behaviour curtailed and the indignity of the Mental Health Act assessment, with police backup to take her off to hospital as she will not recognise the extent of her illness, becomes the inevitable consequence. Lack of insight is the classic feature of madness and is to be expected in mania.

Later stages: The fun of mania rarely lasts long and the initial infectious cheerfulness degenerates into unstoppable destructive irresponsibility. Others trying to bring her back to earth are dismissed, abused and ignored as the bank account gets emptied and exploiters strip her of her assets and dignity. Her ideas become obviously farcical and she becomes a figure of pity if not ridicule. Finally, someone takes action to get her behaviour curtailed and the indignity of the Mental Health Act assessment, with police backup to take her off to hospital as she will not recognise the extent of her illness, becomes the inevitable consequence. Lack of insight is the classic feature of madness and is to be expected in mania.1.5 What psychotic symptoms accompany mania?

Paranoid ideas are the other type of delusion that is commonly seen in manic states. However, it can be difficult to tell when patients’ frustration with others’ lack of enthusiasm for their projects turns to paranoia. Paranoia always has a grandiose edge to it: ‘Why on earth would the CIA be interested in following you?’ Sometimes the mixture is more interesting–for example the man who has to leave the hospital as he is the only one who can tackle the drug traffickers who are in turn out to kill him. But remember paranoid ideas are common in a wide variety of psychiatric disorders (including confusional states) and are certainly not diagnostic of mania.

1.7 What is hypomania?

As the name suggests (Greek, hypo, under), hypomania is the same condition as mania but with a lesser degree of symptoms and more importantly less impairment and disability. In fact hypomania can be a very desirable state, with the patient feeling very well physically and mentally, having lots of energy, not needing much sleep, thinking fast with lots of ideas and feeling confident. Although there may be lots of ideas, productivity is often low: ‘I’ve got all the ideas but I can’t put anything into practice’. However, unlike mania, concentration can still be good and psychotic symptoms are not present.

1.8 What are the symptoms of depression?

![]() As for mania, the basic symptom of depression has to be a change of mood. The mood is usually described as sad, unhappy, down or even just ‘depressed’. The common feature is that it is a dysphoric and unpleasant mood change. Some patients experience prominent anxiety rather than feeling down; others are very irritable (Box 1.3).

As for mania, the basic symptom of depression has to be a change of mood. The mood is usually described as sad, unhappy, down or even just ‘depressed’. The common feature is that it is a dysphoric and unpleasant mood change. Some patients experience prominent anxiety rather than feeling down; others are very irritable (Box 1.3).

Energy: Energy is low–‘the switch has been turned off’. The depressed feel tired all the time; even minor tasks can seem too much and some will spend the whole day in bed doing nothing. The lack of energy may be obvious to others as they see the patient just sit apparently doing nothing and sometimes hardly even moving. Speech can be very slow with long gaps and the patient seems to take an age to answer a simple question. This does seem to be an actual slowing of the thought processes and patients do come to the right answer if you wait long enough. Others may be very agitated, pacing around wringing their hands, sighing, not able to sit down and endlessly restless, not knowing what to do with themselves.

Energy: Energy is low–‘the switch has been turned off’. The depressed feel tired all the time; even minor tasks can seem too much and some will spend the whole day in bed doing nothing. The lack of energy may be obvious to others as they see the patient just sit apparently doing nothing and sometimes hardly even moving. Speech can be very slow with long gaps and the patient seems to take an age to answer a simple question. This does seem to be an actual slowing of the thought processes and patients do come to the right answer if you wait long enough. Others may be very agitated, pacing around wringing their hands, sighing, not able to sit down and endlessly restless, not knowing what to do with themselves. Memory and concentration: Memory is decreased, sometimes to the point that patients think they must be starting to dement because they cannot remember straightforward things like the name of a friend or what they have gone into the garage to get–though all of us experience this at times! This is at least partly due to concentration being poor. This can be a lack of attention–for example when reading, although the words on the page go in, they are not registered, and the patient cannot give an account of the content.

Memory and concentration: Memory is decreased, sometimes to the point that patients think they must be starting to dement because they cannot remember straightforward things like the name of a friend or what they have gone into the garage to get–though all of us experience this at times! This is at least partly due to concentration being poor. This can be a lack of attention–for example when reading, although the words on the page go in, they are not registered, and the patient cannot give an account of the content. Negative thoughts: The world of the depressed is focused internally which can prevent events outside being either recognised or given much importance. Many of the depressed are distracted by their own unpleasant thoughts going round and round so that the only things they can concentrate on are the negative ideas that are dominating thinking. When depressed there is a strong negative bias to all the thinking processes. Unpleasant memories are much more easily recalled than pleasant ones, so that a patient may be unable to recall anything nice that has happened this year, whereas even apparently minor adversities are readily called to mind.

Negative thoughts: The world of the depressed is focused internally which can prevent events outside being either recognised or given much importance. Many of the depressed are distracted by their own unpleasant thoughts going round and round so that the only things they can concentrate on are the negative ideas that are dominating thinking. When depressed there is a strong negative bias to all the thinking processes. Unpleasant memories are much more easily recalled than pleasant ones, so that a patient may be unable to recall anything nice that has happened this year, whereas even apparently minor adversities are readily called to mind.

Suicide: A negative view of the future is one of the drivers to suicide. The negative bias includes feelings that nothing can change and only bad things can happen from now on, and of only being a burden to loved ones. It is easy to see how, for a depressive, there is only a small step to thinking: ‘Everyone would be better off without me and I would be out of this mental pain if I was dead.’ Thinking about death is almost universal in depression and suicidal thoughts from ‘I sometimes just wish I wouldn’t wake up in the morning’ through to clear ideas of self-harm should be expected.

Suicide: A negative view of the future is one of the drivers to suicide. The negative bias includes feelings that nothing can change and only bad things can happen from now on, and of only being a burden to loved ones. It is easy to see how, for a depressive, there is only a small step to thinking: ‘Everyone would be better off without me and I would be out of this mental pain if I was dead.’ Thinking about death is almost universal in depression and suicidal thoughts from ‘I sometimes just wish I wouldn’t wake up in the morning’ through to clear ideas of self-harm should be expected. Physical manifestations: Some people have prominent physical symptoms when depressed, often exacerbations of prior physical problems such as worsening backache, as they become more sensitive to pain. Others will develop new physical symptoms such as headaches and other tension symptoms or stomach pains, or just feel generally unwell and tired. Depressed patients are likely to worry about these physical symptoms and what they mean, such as thinking that they must have cancer to explain the feeling in the stomach, nausea and weight loss, or that poor memory means dementia is on the horizon.

Physical manifestations: Some people have prominent physical symptoms when depressed, often exacerbations of prior physical problems such as worsening backache, as they become more sensitive to pain. Others will develop new physical symptoms such as headaches and other tension symptoms or stomach pains, or just feel generally unwell and tired. Depressed patients are likely to worry about these physical symptoms and what they mean, such as thinking that they must have cancer to explain the feeling in the stomach, nausea and weight loss, or that poor memory means dementia is on the horizon. Appetite: Loss of appetite and consequently losing weight is the rule, although a few patients report an increase in appetite–often favouring sweet foods.

Appetite: Loss of appetite and consequently losing weight is the rule, although a few patients report an increase in appetite–often favouring sweet foods. Sleep: Sleep problems usually occur and it is unusual to find a depressed patient who is sleeping well. The classic symptom is early morning waking when the patient wakes up, feeling bad and completely unable to get back to sleep or even to relax in bed and rest, despite feeling exhausted. However, initial insomnia is common, when the patient goes to bed tired but suddenly finds that sleep is elusive. Waking frequently during the night is also a common complaint. In fact we all wake a few times at night but don’t remember it because it is brief, but the depressed will wake and then stay awake, possibly because worry sets in. Nightmares are common and the pleasant release of dreams is rare. Some patients will oversleep and spend not only the night but much of the day in bed and asleep, feeling too tired to raise themselves.

Sleep: Sleep problems usually occur and it is unusual to find a depressed patient who is sleeping well. The classic symptom is early morning waking when the patient wakes up, feeling bad and completely unable to get back to sleep or even to relax in bed and rest, despite feeling exhausted. However, initial insomnia is common, when the patient goes to bed tired but suddenly finds that sleep is elusive. Waking frequently during the night is also a common complaint. In fact we all wake a few times at night but don’t remember it because it is brief, but the depressed will wake and then stay awake, possibly because worry sets in. Nightmares are common and the pleasant release of dreams is rare. Some patients will oversleep and spend not only the night but much of the day in bed and asleep, feeling too tired to raise themselves.1.9 What psychotic symptoms occur in bipolar depression?

Hallucinations are usually auditory, i.e. hearing a voice saying nasty things–for example hearing children in a playground shouting ‘Paedophile!’, or a voice saying ‘You’re going to burn in Hell’. Although other modalities of hallucination occur–for example smelling the body rotting–these are uncommon.

1.11 What is a mixed affective state?

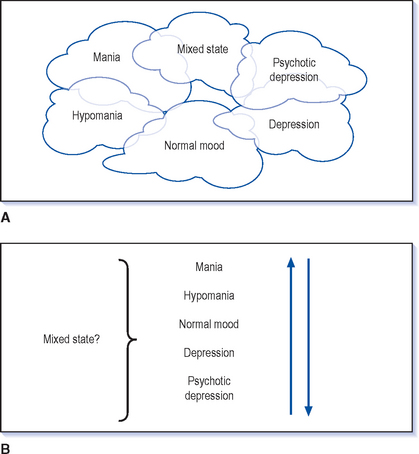

![]() It is probably better to look on mania and depression as closely related states rather than opposites and that they have more in common with each other than with euthymia (Greek, eu, good; thymia, mood)–normal mood (Fig. 1.2A). This makes the understanding of mixed states easier and the more you look for mixed states the more you will see them.

It is probably better to look on mania and depression as closely related states rather than opposites and that they have more in common with each other than with euthymia (Greek, eu, good; thymia, mood)–normal mood (Fig. 1.2A). This makes the understanding of mixed states easier and the more you look for mixed states the more you will see them.

Mixed states are the combination of manic and depressive symptoms at the same time (Fig. 1.2B). Sometimes it is just the presence of depressive ideas: feeling guilty and frightened in an otherwise clear manic state–dysphoric mania (Case vignette 1.1). For others the combination is so marked that you cannot say in which state they are in:

In the morning he can hardly get out of bed but by the evening he’s joking with his children and making wild plans to redecorate the house only to slump back that night.

In the morning he can hardly get out of bed but by the evening he’s joking with his children and making wild plans to redecorate the house only to slump back that night.1.12 What does rapid cycling mean?

However, some patients have a very unstable illness which is frequently changing. Rapid cycling is usually defined as having four episodes in 1 year; this could mean alternating between mania and depression twice in a year or having episodes separated by periods of being in normal mood. The pattern is so variable that one person’s rapid cycling can be very different from that of another. Someone may have six episodes of depression in a year, each lasting a few weeks but then recovery in between; another patient can be ill throughout the year but move several times between mania and depression. The speed of changing between episodes can become very fast so that week to week the patient is in a different phase of the illness and sometimes it becomes so extreme that the illness changes from one day to the next. At this extreme it can be difficult to disentangle from a mixed affective state when people have facets of both mania and depression in the same day (see Q 6.23).

1.14 Do bipolars suffer from other psychiatric problems

Sometimes anxiety is a part of the depression but it is commonly a problem in its own right when patients have otherwise recovered. It is likely that the anxiety problems make a major contribution to the substance misuse as patients try to damp down their symptoms with alcohol or other drugs.

1.15 What is schizoaffective disorder?

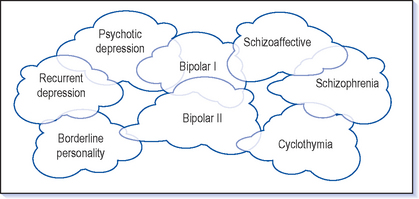

There are also people with clear manic and depressive episodes who, when you saw them in an episode of illness, you would clearly classify as manic depressive. However, when they recover they still have some persistent psychotic symptoms–either delusions or hallucinations–which require treatment in their own right. These people are in the grey area between schizophrenia and manic depression and this is the main group that would be classified as schizoaffective as treatment needs to be focused on both types of symptom (Fig. 1.3 and Case vignette 6.3).

Antipsychotics are the mainstay of treatment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders, but mood symptoms may also be a target for treatment.

1.16 Why does it take several years for some patients to get a correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder?

Many manic episodes are characterised by irritability rather than elation. This is less easy to recognise and more likely to be seen as an aspect of personality rather than as an illness. This can be a particularly difficult problem to unravel but it can be very useful to go through all the symptoms of mania to make as good an assessment as possible.

1.17 How can I improve my ability to diagnose bipolar disorder?

You will be able to find patients that you can clearly classify: those with unipolar recurrent depressions and other patients with a clear manic depressive illness. However, there are a large number of patients in the middle who are much more challenging diagnostically. The two main problems in making the diagnosis are eliciting the symptoms and making a judgement.

ELICITING THE SYMPTOMS

Despite these problems it is worth asking all those who suffer from depression a non-specific question such as: ‘Have there been times when you’ve had the opposite problem to depression; been too high and excited?’ There are some screening questionnaires that can be used and although their discriminatory rate is not good, they do give some examples of useful questions (see Hirschfeld 2000, www.bipolar.com/mdq.htm). It can also be useful to ask an informant such as a spouse or parent, though unfortunately quite often you gain contradictory views from informants and patients. The situation can arise where the patient gives what appears to be a clear history of hypomania but then the relative says they have never noticed any of this!