Cranial nerves 1, 3–6

Traditionally the examination of the cranial nerves is reported according to their numerical order (Box 1). However, during the examination it is easier to group them according to their function – for example, considering the 3rd, 4th and 6th together as eye movements.

Eye movements (3rd, 4th, 6th)

Eye movements are controlled in several ways. They can be moved as follows:

Voluntarily (e.g. look right) – movement is initiated from the frontal eye fields. These are also called saccadic movements.

Voluntarily (e.g. look right) – movement is initiated from the frontal eye fields. These are also called saccadic movements. Under vestibular control, reflex movements maintain eye posture with the head and other movements. This is tested as the vestibulo-ocular reflex, which subserves the doll’s head phenomenon.

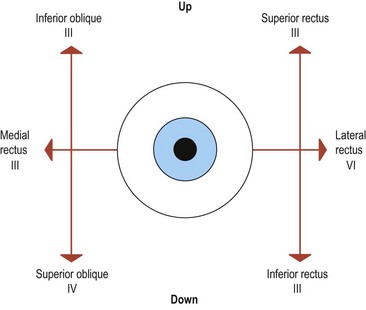

Under vestibular control, reflex movements maintain eye posture with the head and other movements. This is tested as the vestibulo-ocular reflex, which subserves the doll’s head phenomenon.These movements are integrated in the brain stem with the 3rd and 4th nuclei in the midbrain, and the parapontine reticular formation and 6th nerve nucleus in the pons. These are connected by the median longitudinal fasciculus (MLF). Eye movements result from contraction of the extraocular muscles. All but two of the extraocular muscles are supplied by the 3rd nerve, the superior oblique and lateral rectus being supplied by the 4th and 6th nerves, respectively (Fig. 1). Weakness of the extraocular muscles results in double vision in the direction of movement of that muscle. The image that is further out arises from the affected eye. Get the patient to look in the direction where diplopia is maximal and then cover each eye in turn to find which eye sees the outer image. The relative position of the two images is helpful: if the images are horizontally displaced but parallel, this indicates a weakness in the lateral, or occasionally the medial, rectus. If the images are at an angle then other muscles are affected.

In simple terms, examination of eye movements involves answering the following questions:

Infranuclear lesions

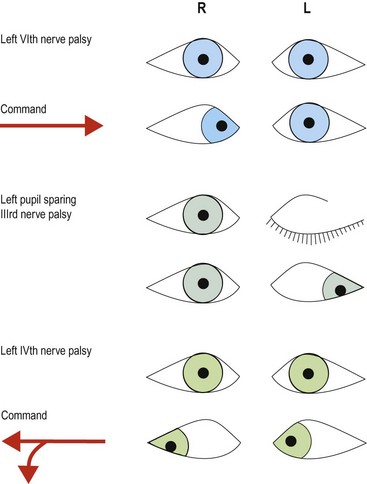

Double vision usually results from a 3rd, 4th or 6th nerve palsy and these are illustrated in Figure 2.

Internuclear and nuclear lesions

Lesions of the nucleus for lateral gaze lead to lateral gaze palsies; this is where neither eye can look in one direction.

Lesions of the nucleus for lateral gaze lead to lateral gaze palsies; this is where neither eye can look in one direction. Inability to look up (upgaze paresis) or look down (downgaze paresis) results from upper and lower brain stem lesions, respectively.

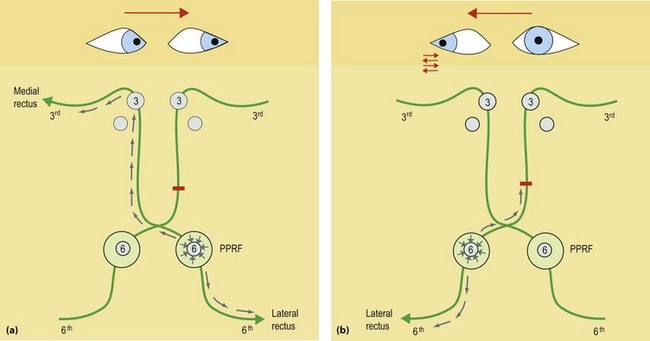

Inability to look up (upgaze paresis) or look down (downgaze paresis) results from upper and lower brain stem lesions, respectively. Lesions to the MLF lead to an internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO; Fig. 3). The lateral gaze nucleus in the pons stimulates the ipsilateral 6th nerve nucleus, causing the ipsilateral eye to abduct; however, the message fails to reach the opposite 3rd nerve nucleus and the contralateral eye does not adduct. This is associated with nystagmus in the abducting eye, so called ataxic nystagmus.

Lesions to the MLF lead to an internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO; Fig. 3). The lateral gaze nucleus in the pons stimulates the ipsilateral 6th nerve nucleus, causing the ipsilateral eye to abduct; however, the message fails to reach the opposite 3rd nerve nucleus and the contralateral eye does not adduct. This is associated with nystagmus in the abducting eye, so called ataxic nystagmus.Nystagmus

The following patterns can be seen:

Pendular nystagmus. This is symmetrical nystagmus in primary gaze, and indicates impaired fixation. It occurs in albinism and, classically, but now rarely, coal miners.

Pendular nystagmus. This is symmetrical nystagmus in primary gaze, and indicates impaired fixation. It occurs in albinism and, classically, but now rarely, coal miners. Unidirectional jerk nystagmus. This can be classified as first degree if it occurs only on looking in the direction of the fast phase, second degree if occurring on primary gaze, and third degree if looking away from the direction of the fast phase. This can occur in central or peripheral vestibular syndromes. Peripheral lesions are associated with vertigo while central ones may not be.

Unidirectional jerk nystagmus. This can be classified as first degree if it occurs only on looking in the direction of the fast phase, second degree if occurring on primary gaze, and third degree if looking away from the direction of the fast phase. This can occur in central or peripheral vestibular syndromes. Peripheral lesions are associated with vertigo while central ones may not be. Multidirectional jerk nystagmus. This indicates a central vestibular syndrome, for example phenytoin toxicity.

Multidirectional jerk nystagmus. This indicates a central vestibular syndrome, for example phenytoin toxicity. Vertical nystagmus. Up- or down-beat nystagmus indicates a central brain stem lesion but has poor localizing value.

Vertical nystagmus. Up- or down-beat nystagmus indicates a central brain stem lesion but has poor localizing value.Vestibular syndromes are discussed further on pages 46–47. Other abnormal eye movements are rare and include opsoclonus or dancing eyes and chaotic movements of the eyes.