Chapter 12 Panniculectomy and Abdominal Wall Reconstruction ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

1 Relevant General Anatomy

When considering panniculectomy in the setting of abdominal hernia repair, the underlying musculature, aponeurotic layers, and adipocutaneous structures are important. The three components are interrelated and should be addressed systematically in order to optimize outcomes following panniculectomy.

When considering panniculectomy in the setting of abdominal hernia repair, the underlying musculature, aponeurotic layers, and adipocutaneous structures are important. The three components are interrelated and should be addressed systematically in order to optimize outcomes following panniculectomy.2 Relevant Muscular Anatomy

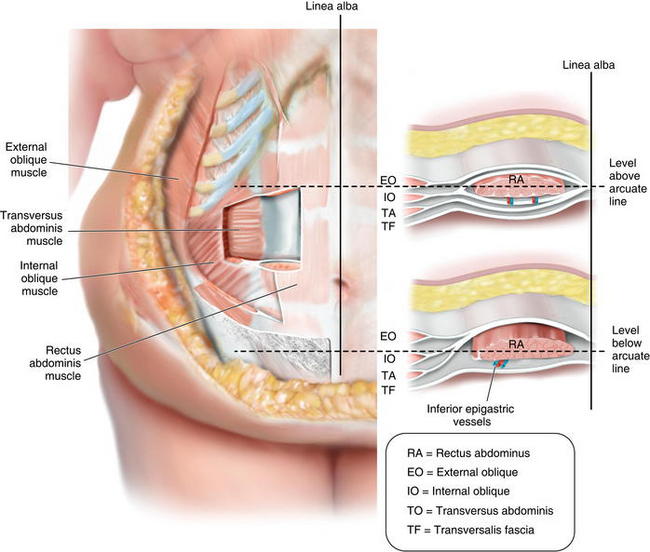

The rectus abdominis and the internal, external, and transverse oblique musculature contribute to the support and contour of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 12-1).

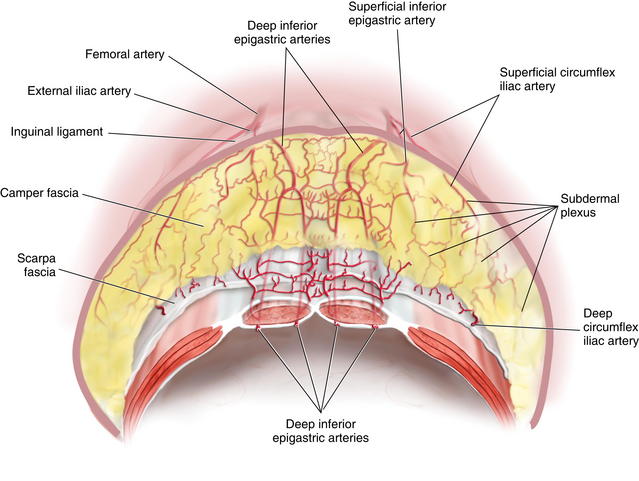

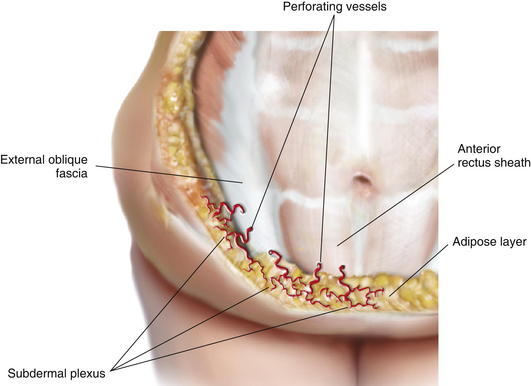

The rectus abdominis and the internal, external, and transverse oblique musculature contribute to the support and contour of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 12-1). The perforating vasculature to the adipocutaneous component of the anterior abdominal wall emanates from the intramuscular vascular network (Fig. 12-2). The majority of significant perforators arise from the deep inferior epigastric system. Other blood vessels contributing to the perforating system include the superficial inferior epigastric artery, superficial circumflex iliac artery, and the deep circumflex iliac artery. All of these perforators converge at the dermis, forming the subdermal plexus.

The perforating vasculature to the adipocutaneous component of the anterior abdominal wall emanates from the intramuscular vascular network (Fig. 12-2). The majority of significant perforators arise from the deep inferior epigastric system. Other blood vessels contributing to the perforating system include the superficial inferior epigastric artery, superficial circumflex iliac artery, and the deep circumflex iliac artery. All of these perforators converge at the dermis, forming the subdermal plexus. Prior abdominal operations associated with undermining can disrupt this perforating vascular network. However, secondary perforators can evolve over time and may be preserved. In addition, as a compensatory mechanism, the remote vascularity will acclimate to the new perfusion patterns and perfuse the undermined tissue.

Prior abdominal operations associated with undermining can disrupt this perforating vascular network. However, secondary perforators can evolve over time and may be preserved. In addition, as a compensatory mechanism, the remote vascularity will acclimate to the new perfusion patterns and perfuse the undermined tissue.3 Relevant Aponeurotic Anatomy

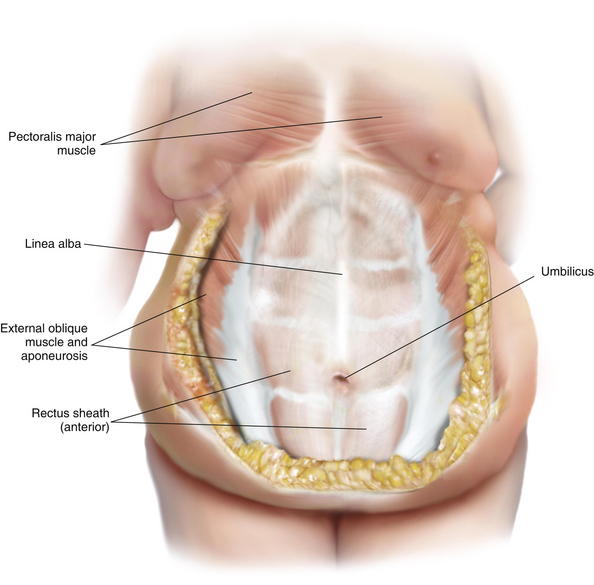

The aponeurotic layers of the anterior abdominal wall include the linea alba, anterior rectus sheath, posterior rectus sheath, and the external oblique fascia (Fig. 12-3).

The aponeurotic layers of the anterior abdominal wall include the linea alba, anterior rectus sheath, posterior rectus sheath, and the external oblique fascia (Fig. 12-3). The anterior rectus sheath and linea alba are composed of collagen fibers arranged in an interwoven lattice. The width and thickness of these structures vary along the surface of the anterior abdominal wall. These measurements fluctuate at various regions of the anterior abdominal wall and are related to the distance from the umbilicus. With respect to the linea alba, its width ranges from 11 to 21 mm between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus and then decreases from 11 to 2 mm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The thickness of the linea alba ranges from 900 to 1200 μm between the xiphoid and the umbilicus and increases from 1700 to 2400 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. With respect to the anterior rectus sheath, the thickness ranges from 370 to 500 μm from the xiphoid to the umbilicus and then increases to 500 to 700 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The posterior rectus sheath, on the other hand, is slightly thicker than the anterior rectus sheath above the umbilicus, ranging from 450 to 600 μm, but then it drops off precipitously from the umbilicus to the arcuate line to 250 to 100 μm.

The anterior rectus sheath and linea alba are composed of collagen fibers arranged in an interwoven lattice. The width and thickness of these structures vary along the surface of the anterior abdominal wall. These measurements fluctuate at various regions of the anterior abdominal wall and are related to the distance from the umbilicus. With respect to the linea alba, its width ranges from 11 to 21 mm between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus and then decreases from 11 to 2 mm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The thickness of the linea alba ranges from 900 to 1200 μm between the xiphoid and the umbilicus and increases from 1700 to 2400 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. With respect to the anterior rectus sheath, the thickness ranges from 370 to 500 μm from the xiphoid to the umbilicus and then increases to 500 to 700 μm from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis. The posterior rectus sheath, on the other hand, is slightly thicker than the anterior rectus sheath above the umbilicus, ranging from 450 to 600 μm, but then it drops off precipitously from the umbilicus to the arcuate line to 250 to 100 μm.2 Preoperative Considerations

As with all operations, proper patient selection is important. A careful assessment of the risks and benefits of panniculectomy must be made, and the patient must be informed of the risks. These risk factors can increase the risk of postoperative morbidity and complications.

As with all operations, proper patient selection is important. A careful assessment of the risks and benefits of panniculectomy must be made, and the patient must be informed of the risks. These risk factors can increase the risk of postoperative morbidity and complications.1 Preoperative Imaging

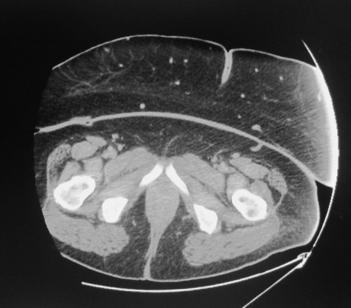

Preoperative imaging is important when considering panniculectomy. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) delineate the size of the hernia defect and provide information regarding the thickness of the abdominal pannus (Fig. 12-6). The abdominal musculature also is appreciated. MRI also permits visualization of the larger arteries and veins that course through the pannus.

Preoperative imaging is important when considering panniculectomy. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) delineate the size of the hernia defect and provide information regarding the thickness of the abdominal pannus (Fig. 12-6). The abdominal musculature also is appreciated. MRI also permits visualization of the larger arteries and veins that course through the pannus.2 Assessment of Risk Factors

Systemic risk factors that require optimization include but are not limited to diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, pulmonary disease, poor nutritional status, cardiac disease, connective tissue disorders, abdominal aortic aneurisms, and immunosuppression. Local risk factors include but are not limited to prior soft tissue or cutaneous infections, fistula, indurated skin, lymphedema, and ulcerations.

Systemic risk factors that require optimization include but are not limited to diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, pulmonary disease, poor nutritional status, cardiac disease, connective tissue disorders, abdominal aortic aneurisms, and immunosuppression. Local risk factors include but are not limited to prior soft tissue or cutaneous infections, fistula, indurated skin, lymphedema, and ulcerations. In patients with an elevated BMI (>35), uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and poor nutritional status, the incidence of complications such as delayed healing, incisional dehiscence, soft tissue necrosis, infection, and prolonged drainage are likely to be increased. The anticipated length of the operation may influence the timing of the panniculectomy, immediate or delayed.

In patients with an elevated BMI (>35), uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and poor nutritional status, the incidence of complications such as delayed healing, incisional dehiscence, soft tissue necrosis, infection, and prolonged drainage are likely to be increased. The anticipated length of the operation may influence the timing of the panniculectomy, immediate or delayed.3 Prior Hernia Surgical History

Prior studies have demonstrated an increased risk of infection in patients with an abdominal hernia. Although, many of these operations appear at first glance to be “clean” operations, they are, in fact, more susceptible to infection. Many of these infections manifest in the skin and subcutaneous fat. The incidence of soft tissue infection is approximately 10-fold higher in patients with a hernia (16% vs. 1.5%). In patients with a prior abdominal hernia repair, the risk of infection continues to increase (42% vs. 12%). Surgeons should be cognizant of these statistics when considering panniculectomy.

Prior studies have demonstrated an increased risk of infection in patients with an abdominal hernia. Although, many of these operations appear at first glance to be “clean” operations, they are, in fact, more susceptible to infection. Many of these infections manifest in the skin and subcutaneous fat. The incidence of soft tissue infection is approximately 10-fold higher in patients with a hernia (16% vs. 1.5%). In patients with a prior abdominal hernia repair, the risk of infection continues to increase (42% vs. 12%). Surgeons should be cognizant of these statistics when considering panniculectomy. In general, prior vertical midline incisions are preferred because a fleur-de-lis pattern can be used. With this pattern, excess skin and fat can be excised in both the horizontal and vertical planes. When the prior incisions are transverse in orientation, problems related to blood supply can occur, especially when the incisions are located in the mid- and upper abdominal areas. Low transverse abdominal incisions are usually fine because this is where the transverse incisions are usually made for panniculectomy.

In general, prior vertical midline incisions are preferred because a fleur-de-lis pattern can be used. With this pattern, excess skin and fat can be excised in both the horizontal and vertical planes. When the prior incisions are transverse in orientation, problems related to blood supply can occur, especially when the incisions are located in the mid- and upper abdominal areas. Low transverse abdominal incisions are usually fine because this is where the transverse incisions are usually made for panniculectomy.3 Operative Steps

Preparing for panniculectomy is in many ways similar to preparing for abdominoplasty. The principles and concepts for the two are similar. Design patterns for skin excision must consider the vascularity of the skin. This will be related to the location of the prior incisions, the thickness of the soft tissues, and the degree of undermining. The degree of soft tissue undermining must include an appreciation for the thickness of the pannus because this can impact the perfusion of the adipocutaneous component.

Preparing for panniculectomy is in many ways similar to preparing for abdominoplasty. The principles and concepts for the two are similar. Design patterns for skin excision must consider the vascularity of the skin. This will be related to the location of the prior incisions, the thickness of the soft tissues, and the degree of undermining. The degree of soft tissue undermining must include an appreciation for the thickness of the pannus because this can impact the perfusion of the adipocutaneous component.1 Design Patterns for Panniculectomy

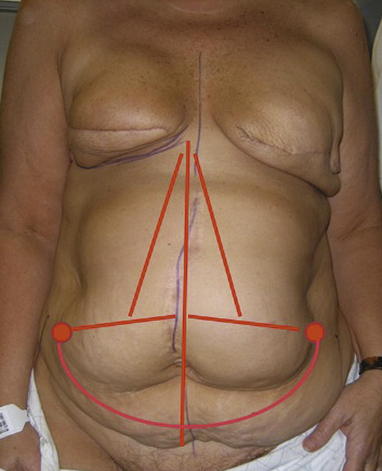

There are several design patterns for abdominal panniculectomy. These include the horizontal incision; vertical incision; and a horizontal and vertical incision, also known as a fleur-de-lis pattern (Fig. 12-7). The specific pattern depends on the location of excess tissue and the location of prior incisions. Most patients with abdominal hernias will have a prior vertical midline incision. Incorporating this into the excision pattern is useful and does not usually result in additional scars.

There are several design patterns for abdominal panniculectomy. These include the horizontal incision; vertical incision; and a horizontal and vertical incision, also known as a fleur-de-lis pattern (Fig. 12-7). The specific pattern depends on the location of excess tissue and the location of prior incisions. Most patients with abdominal hernias will have a prior vertical midline incision. Incorporating this into the excision pattern is useful and does not usually result in additional scars.2 Technique of Perforator Sparing

In patients with abdominal hernias and excess abdominal skin and fat, some degree of soft tissue undermining is usually necessary in order to adequately close and contour the abdominal wall. The undermining is always at the junction of the fascia and fat. All of the perforators supplying the skin and fat pierce the fascia (see Fig. 12-5). Preservation of one or more perforators improves the vascularity of the adipocutaneous layer and minimizes the incidence of delayed healing or skin necrosis.

In patients with abdominal hernias and excess abdominal skin and fat, some degree of soft tissue undermining is usually necessary in order to adequately close and contour the abdominal wall. The undermining is always at the junction of the fascia and fat. All of the perforators supplying the skin and fat pierce the fascia (see Fig. 12-5). Preservation of one or more perforators improves the vascularity of the adipocutaneous layer and minimizes the incidence of delayed healing or skin necrosis. Undermining can be performed using electrocautery or blunt dissection techniques. A blunt, tapered-point surgical scissor or clamp can be used to separate the perforator from the surrounding fat. An alternative approach is to use a low-voltage electrocautery device with a fine-tip surgical clamp.

Undermining can be performed using electrocautery or blunt dissection techniques. A blunt, tapered-point surgical scissor or clamp can be used to separate the perforator from the surrounding fat. An alternative approach is to use a low-voltage electrocautery device with a fine-tip surgical clamp. In general, smaller perforators (<1 mm) are usually cauterized. Larger perforators (1.0 to 2.5 mm) can be preserved. The presence of a palpable pulse in the perforator is recommended when considering preservation.

In general, smaller perforators (<1 mm) are usually cauterized. Larger perforators (1.0 to 2.5 mm) can be preserved. The presence of a palpable pulse in the perforator is recommended when considering preservation. The number of perforators to be spared is also variable and depends on the body habitus and the thickness of the abdominal pannus. Personal experience has demonstrated that preservation of a single perforating vessel on each side of the hemiabdomen is usually adequate. Surgeons also should be aware that in some patients with multiple hernia repairs, perforating vessels may no longer be present.

The number of perforators to be spared is also variable and depends on the body habitus and the thickness of the abdominal pannus. Personal experience has demonstrated that preservation of a single perforating vessel on each side of the hemiabdomen is usually adequate. Surgeons also should be aware that in some patients with multiple hernia repairs, perforating vessels may no longer be present.3 Technique of Skin/Fat Excision

Preoperative markings are important. With the patient in the standing position, the amount of excess skin is approximated by grasping and elevating the pannus (Fig. 12-8). The markings typically include the incision for the hernia repair and the incisions for the panniculectomy (Fig. 12-9).

Preoperative markings are important. With the patient in the standing position, the amount of excess skin is approximated by grasping and elevating the pannus (Fig. 12-8). The markings typically include the incision for the hernia repair and the incisions for the panniculectomy (Fig. 12-9). Before the operative incisions, measures to control and limit blood loss may be considered. One such maneuver is to place tumescent fluid into the soft tissues of the pannus. The typical tumescent solution consists of 1 ml of 1:1000 epinephrine solution per liter of lactated Ringer solution.

Before the operative incisions, measures to control and limit blood loss may be considered. One such maneuver is to place tumescent fluid into the soft tissues of the pannus. The typical tumescent solution consists of 1 ml of 1:1000 epinephrine solution per liter of lactated Ringer solution. Typically, the panniculectomy is performed after the hernia has been completed. This is important in order to better assess the exact amount of skin and fat to be excised. In cases where an open component separation has been performed, it is important to preserve perforators when possible to optimize skin perfusion.

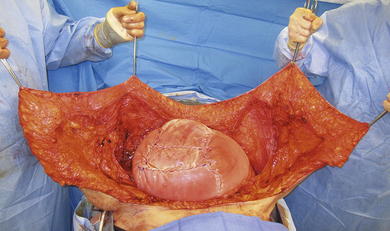

Typically, the panniculectomy is performed after the hernia has been completed. This is important in order to better assess the exact amount of skin and fat to be excised. In cases where an open component separation has been performed, it is important to preserve perforators when possible to optimize skin perfusion. Once the hernia repair is complete, the soft tissues are further undermined off of the anterior rectus sheath, and the amount of excess skin and fat is determined (Fig. 12-10). The degree of undermining depends on the thickness of the adipocutaneous tissues, location of scars, and assessment of skin vascularity. Vertical skin excisions are performed by elevating the adipocutaneous flaps and redraping one side over the other (Fig. 12-11). The overlapping areas are marked before excision (Fig. 12-12). Vertical and horizontal skin excisions proceed, incorporating the vertical and horizontal incisions (Fig. 12-13). It is important to excise any abnormal or thickened skin. The vascularity of the remaining skin flaps is based superolaterally. In patients with a very large or thick pannus, it is important to avoid extensive undermining that may compromise vascularity.

Once the hernia repair is complete, the soft tissues are further undermined off of the anterior rectus sheath, and the amount of excess skin and fat is determined (Fig. 12-10). The degree of undermining depends on the thickness of the adipocutaneous tissues, location of scars, and assessment of skin vascularity. Vertical skin excisions are performed by elevating the adipocutaneous flaps and redraping one side over the other (Fig. 12-11). The overlapping areas are marked before excision (Fig. 12-12). Vertical and horizontal skin excisions proceed, incorporating the vertical and horizontal incisions (Fig. 12-13). It is important to excise any abnormal or thickened skin. The vascularity of the remaining skin flaps is based superolaterally. In patients with a very large or thick pannus, it is important to avoid extensive undermining that may compromise vascularity. In cases where the hernia is extremely large and associated with a loss of domain in which the hernia sac is lining the deep fat layer, the sac or scar is excised because it may be a nidus for infection. The skin flaps are then elevated and redraped in order to determine how much will be excised. Skin excision is performed sharply to minimize any thermal damage to the edges.

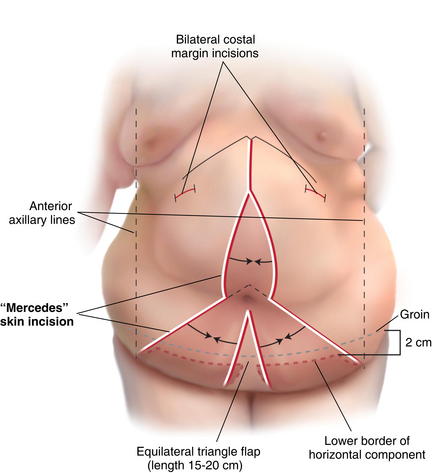

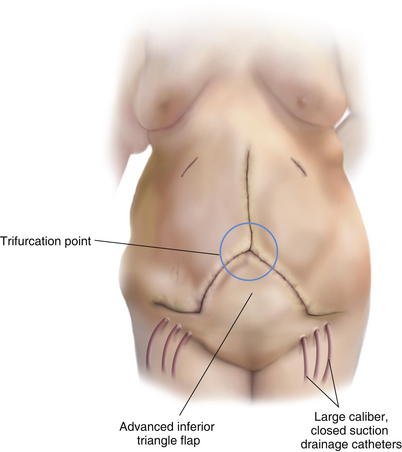

In cases where the hernia is extremely large and associated with a loss of domain in which the hernia sac is lining the deep fat layer, the sac or scar is excised because it may be a nidus for infection. The skin flaps are then elevated and redraped in order to determine how much will be excised. Skin excision is performed sharply to minimize any thermal damage to the edges. An alternative technique for skin pattern design and excision is the “Mercedes” approach (Figs. 12-14 and 12-15). This technique is indicated in patients in whom a vertical and horizontal skin excision is necessary. The advantage of this pattern is that it will preserve vascularized tissue at the trifurcation point and potentially minimize the delayed healing and skin necrosis that often occurs there. In preparation for this technique, the vertical midline and transverse horizontal patterns are delineated much like the standard techniques. The unique feature of this design is that an equilateral triangular pattern is delineated just below the umbilicus extending to the horizontal markings. The lengths of these triangular limbs are usually 15 to 20 cm and vary, based on body habitus and the dimensions of the pannus. This triangular skin is not excised with the panniculectomy. It is preserved as a caudally based flap that is advanced in the cephalad direction following the central and lateral skin excisions.

An alternative technique for skin pattern design and excision is the “Mercedes” approach (Figs. 12-14 and 12-15). This technique is indicated in patients in whom a vertical and horizontal skin excision is necessary. The advantage of this pattern is that it will preserve vascularized tissue at the trifurcation point and potentially minimize the delayed healing and skin necrosis that often occurs there. In preparation for this technique, the vertical midline and transverse horizontal patterns are delineated much like the standard techniques. The unique feature of this design is that an equilateral triangular pattern is delineated just below the umbilicus extending to the horizontal markings. The lengths of these triangular limbs are usually 15 to 20 cm and vary, based on body habitus and the dimensions of the pannus. This triangular skin is not excised with the panniculectomy. It is preserved as a caudally based flap that is advanced in the cephalad direction following the central and lateral skin excisions.4 Closure Techniques

Before skin closure, the wounds are copiously irrigated with an antibiotic solution. Closed suction drains are placed in the lateral gutters and as needed for the hernia repair. These drains are usually large caliber and can be inserted through the incision or via a remote skin site. The closure is completed in layers using absorbable sutures in the Scarpa layer and the dermis. The cutaneous closure can be performed using staples or sutures, depending on the perceived risks of infection, delayed healing, and incisional dehiscence.

Before skin closure, the wounds are copiously irrigated with an antibiotic solution. Closed suction drains are placed in the lateral gutters and as needed for the hernia repair. These drains are usually large caliber and can be inserted through the incision or via a remote skin site. The closure is completed in layers using absorbable sutures in the Scarpa layer and the dermis. The cutaneous closure can be performed using staples or sutures, depending on the perceived risks of infection, delayed healing, and incisional dehiscence. In some cases, the incision is not closed completely and a negative pressure wound therapy device is applied (Fig. 12-16). The reasoning for this is to minimize potential fluid collections and soft tissue edema. Once stable, this device can be removed and the wound closed secondarily.

In some cases, the incision is not closed completely and a negative pressure wound therapy device is applied (Fig. 12-16). The reasoning for this is to minimize potential fluid collections and soft tissue edema. Once stable, this device can be removed and the wound closed secondarily.4 Postoperative Care

1 Hospital Care

Antibiotics: Postoperatively, patients are continued on intravenous antibiotic. In some centers, antibiotic coverage is delivered during the perioperative period (24 hours). However, personal experience has been favorable with a 1-week duration. This may be prolonged in the setting of a postoperative infection.

Antibiotics: Postoperatively, patients are continued on intravenous antibiotic. In some centers, antibiotic coverage is delivered during the perioperative period (24 hours). However, personal experience has been favorable with a 1-week duration. This may be prolonged in the setting of a postoperative infection. Drains: The duration of the drains is variable and based on quantity of fluid and the need for prolonged suction to promote tissue adherence. Typically, drains are removed when the output is <30 mL/drain/day and usually left in place for 1 to 2 weeks.

Drains: The duration of the drains is variable and based on quantity of fluid and the need for prolonged suction to promote tissue adherence. Typically, drains are removed when the output is <30 mL/drain/day and usually left in place for 1 to 2 weeks. Venous thromboembolism (VTE): All patients following hernia repair and panniculectomy will require VTE prophylaxis in the form of pneumatic compression devices and chemoprevention using pharmaceutical agents such as Lovenox or subcutaneous heparin. Pulmonary consideration may be relevant because the added pressure on the diaphragm from the hernia repair and the panniculectomy may increase airway resistance. Incentive spirometry and early ambulation are encouraged to improve pulmonary status and circulation.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE): All patients following hernia repair and panniculectomy will require VTE prophylaxis in the form of pneumatic compression devices and chemoprevention using pharmaceutical agents such as Lovenox or subcutaneous heparin. Pulmonary consideration may be relevant because the added pressure on the diaphragm from the hernia repair and the panniculectomy may increase airway resistance. Incentive spirometry and early ambulation are encouraged to improve pulmonary status and circulation. Nutrition: Nutritional status is assessed and diets are advanced as tolerated once bowel function has returned. In some situations when enteral feeding is not possible early, parenteral feeding is advised.

Nutrition: Nutritional status is assessed and diets are advanced as tolerated once bowel function has returned. In some situations when enteral feeding is not possible early, parenteral feeding is advised. Length of stay: The length of hospital stay is variable and depends on various factors. These include but are not limited to return of bowel function, development of complications, and patient compliance. Reid and Dumanian (2005) have determined that the average length of stay in patients who have component separation repair of an abdominal hernia with panniculectomy was 7.7 days.

Length of stay: The length of hospital stay is variable and depends on various factors. These include but are not limited to return of bowel function, development of complications, and patient compliance. Reid and Dumanian (2005) have determined that the average length of stay in patients who have component separation repair of an abdominal hernia with panniculectomy was 7.7 days.2 Home Care

Following hernia repair and panniculectomy, patients are instructed to minimize strenuous activities for 6 weeks. The use of an abdominal binder is appropriate once it is known that tissue viability is certain. Patients may shower and get the incision wet on day 3 following surgery, if possible. Most patients will require a convalescence period of 1 to 2 months following surgery.

Following hernia repair and panniculectomy, patients are instructed to minimize strenuous activities for 6 weeks. The use of an abdominal binder is appropriate once it is known that tissue viability is certain. Patients may shower and get the incision wet on day 3 following surgery, if possible. Most patients will require a convalescence period of 1 to 2 months following surgery.5 Management of Complications

When performing panniculectomies in patients with abdominal hernias, one should not be surprised in the event of complications. In the majority of cases, complications are infection, soft tissue necrosis, and delayed healing or incisional dehiscence. Studies have demonstrated that the incidence of a major postoperative wound complication in increased sixfold when the BMI is greater than 35, and that those patients are 5 times more likely to undergo reoperation.

When performing panniculectomies in patients with abdominal hernias, one should not be surprised in the event of complications. In the majority of cases, complications are infection, soft tissue necrosis, and delayed healing or incisional dehiscence. Studies have demonstrated that the incidence of a major postoperative wound complication in increased sixfold when the BMI is greater than 35, and that those patients are 5 times more likely to undergo reoperation. Infection: Postoperative wound infections typically manifest within a few days and may present with cellulitis or drainage (Fig. 12-17). Appropriate cultures and sensitivities are obtained. Infectious disease consultation is recommended and based on surgeon comfort and extent of disease. Causative organisms are variable and may include staphylococcus, streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and others. Surgical incision and drainage procedures may be necessary.

Infection: Postoperative wound infections typically manifest within a few days and may present with cellulitis or drainage (Fig. 12-17). Appropriate cultures and sensitivities are obtained. Infectious disease consultation is recommended and based on surgeon comfort and extent of disease. Causative organisms are variable and may include staphylococcus, streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and others. Surgical incision and drainage procedures may be necessary. Soft tissue necrosis: Impaired vascular circulation, increased tension, or soft tissue infection may result in tissue necrosis (see Fig. 12-17). Surgical debridement is necessary. The debridement must include all necrotic tissue and extend to viable, bleeding tissue. Closure immediately following debridement is usually not performed. Local wound measures are implemented and may include wet to dry dressings or enzymatic measures. Secondary closure is considered when all signs of infection and necrosis are cleared.

Soft tissue necrosis: Impaired vascular circulation, increased tension, or soft tissue infection may result in tissue necrosis (see Fig. 12-17). Surgical debridement is necessary. The debridement must include all necrotic tissue and extend to viable, bleeding tissue. Closure immediately following debridement is usually not performed. Local wound measures are implemented and may include wet to dry dressings or enzymatic measures. Secondary closure is considered when all signs of infection and necrosis are cleared. Incisional dehiscence: Dehiscence can occur because of tension or abnormal forces being placed upon the incision. In the event of a pure dehiscence, secondary closure may be indicated, However, in the event of contamination, local wound measures may be indicated for a period of time, followed by delayed secondary closure.

Incisional dehiscence: Dehiscence can occur because of tension or abnormal forces being placed upon the incision. In the event of a pure dehiscence, secondary closure may be indicated, However, in the event of contamination, local wound measures may be indicated for a period of time, followed by delayed secondary closure.6 Pearls and Pitfalls

Set expectations: Before any of these procedures, it is important to set expectations during the initial and subsequent preoperative consultations. Complications are common, and patients with abdominal hernias, pannus formation, and associated comorbidities must be aware of the potential adverse events.

Set expectations: Before any of these procedures, it is important to set expectations during the initial and subsequent preoperative consultations. Complications are common, and patients with abdominal hernias, pannus formation, and associated comorbidities must be aware of the potential adverse events. Avoid the “hand-in-glove” fit: When excising excess skin, it is tempting to maximally excise to obtain optimal contour. Avoid this temptation. Postoperative soft tissue edema may result in increased tension. In addition, postoperative complications such as dehiscence or soft tissue necrosis may result in an inability to achieve closure when desired. Leaving a small amount of skin redundancy is not a problem. It can be easily corrected a few months later once all healing is complete.

Avoid the “hand-in-glove” fit: When excising excess skin, it is tempting to maximally excise to obtain optimal contour. Avoid this temptation. Postoperative soft tissue edema may result in increased tension. In addition, postoperative complications such as dehiscence or soft tissue necrosis may result in an inability to achieve closure when desired. Leaving a small amount of skin redundancy is not a problem. It can be easily corrected a few months later once all healing is complete. Negative pressure wound therapy: In some situations where the risk of soft tissue infection or delayed healing is considered high, it may be advantageous to leave a portion of the incision open. The application of a negative pressure wound therapy device is advised in these situations. The benefits include controlling edema, reducing tension on the incision line, and serving as an exit portal for excess fluid.

Negative pressure wound therapy: In some situations where the risk of soft tissue infection or delayed healing is considered high, it may be advantageous to leave a portion of the incision open. The application of a negative pressure wound therapy device is advised in these situations. The benefits include controlling edema, reducing tension on the incision line, and serving as an exit portal for excess fluid. In situations where the thickness of the abdominal pannus is extreme (>6 cm), excision of the loose fat to the level of Scarpa fascia is appropriate and can facilitate closure.

In situations where the thickness of the abdominal pannus is extreme (>6 cm), excision of the loose fat to the level of Scarpa fascia is appropriate and can facilitate closure. In morbidly obese patients (BMI >40) with a large abdominal pannus, weight loss measures are advised when possible. This may potentially decrease the postoperative complications that are likely in this population.

In morbidly obese patients (BMI >40) with a large abdominal pannus, weight loss measures are advised when possible. This may potentially decrease the postoperative complications that are likely in this population.Askar O.M. Surgical anatomy of the aponeurotic expansions of the anterior abdominal wall. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1977;59:313-321.

Axer H., v. Keyserlingk D.G., Prescher A. Collagen fibers in linea alba and rectus sheaths: I. General scheme and morphological aspects. Journal of Surgical Research. 2001;96:127-134.

Axer H., v. Keyserlingk D.G., Prescher A. Collagen fibers in linea alba and rectus sheaths II. Variability and biomechanical aspects. Journal of Surgical Research. 2001;96:239-245.

Borud L.J., Grunwaldt L., Janz B., Mun E., Slavin S.A. Components separation combined with abdominal wall plication for repair of large abdominal wall hernias following bariatric surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1792.

Butler C.E., Reis S.M. Mercedes panniculectomy with simultaneous component separation ventral hernia repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:94.

Cooper C.M., Paige K.T., Beshlian K.M., Downey D.L., Thrilby R.C. Abdominal panniculectomies: High patient satisfaction despite significant complication rates. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:188-196.

Houck J.P., Rypins E.B., Sarfeh I.J., Juler G.L., Shimoda K.J. Repair of incisional hernia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:397.

Korenkov M., Beckers A., Koebke J., et al. Biomechanical and morphological types of the linea alba and its possible role in the pathogenesis of midline incisional hernia. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:909-914.

Nahabedian M.Y., Manson P.N. Contour abnormalities of the abdomen following TRAM Flap breast reconstruction: A Multifactorial Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:81-87.

Nahabedian M.Y., Dooley W., Singh N., Manson P.N. Contour Abnormalities of the abdomen following breast reconstruction with abdominal flaps: The role of muscle preservation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:91-101.

Reid R.R., Dumanian G.A. Panniculectomy and the separation-of-parts hernia repair: A solution for the large infraumbillical hernia in the obese patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1006.

Saulis A.S., Dumanian G.A. Periumbilical rectus abdominis perforator preservation significantly reduces superficial wound complications in “separation of parts” hernia repairs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2275.