Chapter 18 Biologic Mesh Choices for Surgical Repair

1 Indications for the Use of Biologic Mesh Materials

The major indication for the use of biologic meshes during abdominal wall surgery is improved wound healing. This most often translates into the minimization of wound complications. Studies have reported wound infection rates of 4% to 16% after incisional ventral hernia repair. The application of synthetic mesh to reinforce abdominal wall repairs significantly reduced recurrence rates, but it introduced an increased risk of complicated wound infections, synthetic mesh infections and erosion into the bowel. Level one data find that recurrence rate and wound infection are related, in that a postoperative wound infection significantly increases the incidence of recurrent incisional hernia. Another inherent limitation with synthetic meshes is shrinkage. It is well measured now in animal models and with human explants that synthetic meshes lose on the average 20% of their surface area following implantation. This is believed to contribute to high hernia recurrence rates. The era of managing traumatized patients with open abdomens expanded the use of biologic mesh based abdominal wall reconstruction. Here there was concern for wound contamination and exposure of synthetic prostheses to the abdominal viscera. Tenuous or insufficient skin coverage also is suggested as an indication for the use of a biologic mesh during abdominal wall repair.

The major indication for the use of biologic meshes during abdominal wall surgery is improved wound healing. This most often translates into the minimization of wound complications. Studies have reported wound infection rates of 4% to 16% after incisional ventral hernia repair. The application of synthetic mesh to reinforce abdominal wall repairs significantly reduced recurrence rates, but it introduced an increased risk of complicated wound infections, synthetic mesh infections and erosion into the bowel. Level one data find that recurrence rate and wound infection are related, in that a postoperative wound infection significantly increases the incidence of recurrent incisional hernia. Another inherent limitation with synthetic meshes is shrinkage. It is well measured now in animal models and with human explants that synthetic meshes lose on the average 20% of their surface area following implantation. This is believed to contribute to high hernia recurrence rates. The era of managing traumatized patients with open abdomens expanded the use of biologic mesh based abdominal wall reconstruction. Here there was concern for wound contamination and exposure of synthetic prostheses to the abdominal viscera. Tenuous or insufficient skin coverage also is suggested as an indication for the use of a biologic mesh during abdominal wall repair. The risk of laparotomy wound complications may be graded and wound outcomes predicted based on patient comorbidities and level of contamination. Now long-term experience with synthetic meshes in the abdominal wall raises awareness and concern for acute and chronic infections, as well as intestinal injury. The growing problem of infected mesh explantation also drove increased use of biologic meshes as replacements. Obesity is now a measurable risk factor for increased wound complications following ventral hernia repair.

The risk of laparotomy wound complications may be graded and wound outcomes predicted based on patient comorbidities and level of contamination. Now long-term experience with synthetic meshes in the abdominal wall raises awareness and concern for acute and chronic infections, as well as intestinal injury. The growing problem of infected mesh explantation also drove increased use of biologic meshes as replacements. Obesity is now a measurable risk factor for increased wound complications following ventral hernia repair. The growing popularity of major reconstructive procedures for large ventral hernias also expanded the use of biologic meshes. The perceived need for reinforcement following component separation procedures and the concern for the implantation of synthetic materials into these large surface area wounds led to this adaptation of biologic mesh. Clinical studies have supported reduced recurrence rates using mesh reinforcement during component separation.

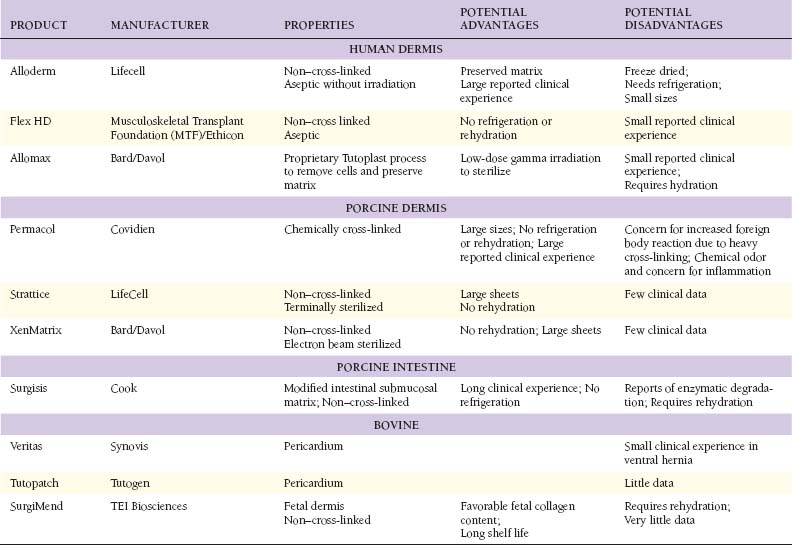

The growing popularity of major reconstructive procedures for large ventral hernias also expanded the use of biologic meshes. The perceived need for reinforcement following component separation procedures and the concern for the implantation of synthetic materials into these large surface area wounds led to this adaptation of biologic mesh. Clinical studies have supported reduced recurrence rates using mesh reinforcement during component separation.2 Tissue Sources for Biologic Mesh Materials (Table 18-1)

The application of biologic materials to abdominal wall repair began with autologous source material. Tensor fascia lata (TFL) has the widest experience. De-epithelialized autologous dermis also has been used. Muscle flaps and now even composite tissue transfers, both pedicle based and free flaps, have been described. Autologous small bowel and omentum also are reported as tissue sources for abdominal wall repair. Donor site morbidity is the obvious limitation of autologous biologic tissue sources. There are no large studies of TFL or autologous dermis in abdominal wall repair, and the long-term durability, especially when used as bridging repair, is not known.

The application of biologic materials to abdominal wall repair began with autologous source material. Tensor fascia lata (TFL) has the widest experience. De-epithelialized autologous dermis also has been used. Muscle flaps and now even composite tissue transfers, both pedicle based and free flaps, have been described. Autologous small bowel and omentum also are reported as tissue sources for abdominal wall repair. Donor site morbidity is the obvious limitation of autologous biologic tissue sources. There are no large studies of TFL or autologous dermis in abdominal wall repair, and the long-term durability, especially when used as bridging repair, is not known. The need for more readily available biologic reconstructive matrices and the limitation of autologous tissue donor site morbidity led to the development of off-the-shelf human allograft sources for abdominal wall reconstruction. To date, this has been dominated by human dermal allografts. Although early results have been good, there is an inherent limitation in the need for human tissue banking and the risk of transmission of infectious disease. Before processing, potential donors undergo screening that includes a medical and social history review, physical examination and serologic testing to minimize the risk of disease transmission. Donor tissue that passes rigorous screening then undergoes physical and chemical processing to further reduce the risk of disease transmission before implantation. Occasionally, social and cultural restrictions may preclude the application of human tissue sources to specific patient groups.

The need for more readily available biologic reconstructive matrices and the limitation of autologous tissue donor site morbidity led to the development of off-the-shelf human allograft sources for abdominal wall reconstruction. To date, this has been dominated by human dermal allografts. Although early results have been good, there is an inherent limitation in the need for human tissue banking and the risk of transmission of infectious disease. Before processing, potential donors undergo screening that includes a medical and social history review, physical examination and serologic testing to minimize the risk of disease transmission. Donor tissue that passes rigorous screening then undergoes physical and chemical processing to further reduce the risk of disease transmission before implantation. Occasionally, social and cultural restrictions may preclude the application of human tissue sources to specific patient groups. The unique regulatory limitations of human tissue banking and the need for better processing quality control drove the introduction of xenografts as biologic materials for abdominal wall reconstruction. This also reduces the cost of xenografts that on the average are 50% less expensive than allografts. This trend has been dominated by porcine intestinal submucosa, porcine dermis, bovine fetal dermis, and bovine adult pericardium. One fundamental limitation of xenografts is the presence in humans of preformed anti-xenograft antibodies. The anti-galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose antibodies are the best described. There is also evidence for the induction of nonspecific inflammatory pathways as part of a generalized foreign body reaction. With xenografts as with allografts, social and cultural restrictions may apply.

The unique regulatory limitations of human tissue banking and the need for better processing quality control drove the introduction of xenografts as biologic materials for abdominal wall reconstruction. This also reduces the cost of xenografts that on the average are 50% less expensive than allografts. This trend has been dominated by porcine intestinal submucosa, porcine dermis, bovine fetal dermis, and bovine adult pericardium. One fundamental limitation of xenografts is the presence in humans of preformed anti-xenograft antibodies. The anti-galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose antibodies are the best described. There is also evidence for the induction of nonspecific inflammatory pathways as part of a generalized foreign body reaction. With xenografts as with allografts, social and cultural restrictions may apply.3 Biologic Mesh Modification and Processing

The use of biologic allografts and xenografts for soft tissue repair required the development of processing techniques that allowed for the removal of immunogenic cells, while preserving a functional biologic matrix. This remnant biologic matrix is constructed primarily of collagen, and depending on the degree of preservation of the native structure, maintains measurable biologic function even in the acellularized state.

The use of biologic allografts and xenografts for soft tissue repair required the development of processing techniques that allowed for the removal of immunogenic cells, while preserving a functional biologic matrix. This remnant biologic matrix is constructed primarily of collagen, and depending on the degree of preservation of the native structure, maintains measurable biologic function even in the acellularized state. Porcine intestinal submucosa is a readily available source of biologic matrix. In its varied forms it maintains adequate mechanical qualities and has a recognized safety profile when applied for abdominal wall repair or reconstruction. The proprietary process for stripping and harvesting the intestinal submucosa results in modification of the original biologic structure. Intestinal submucosa also has been laminated to improve mechanical performance.

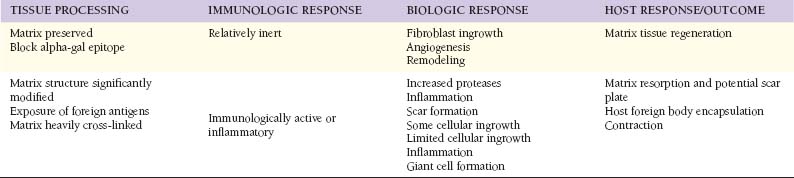

Porcine intestinal submucosa is a readily available source of biologic matrix. In its varied forms it maintains adequate mechanical qualities and has a recognized safety profile when applied for abdominal wall repair or reconstruction. The proprietary process for stripping and harvesting the intestinal submucosa results in modification of the original biologic structure. Intestinal submucosa also has been laminated to improve mechanical performance. The importance of preserving the native dermal matrix structure and to what degree is still debated. Cross-linking of dermal matrix xenografts was introduced as a method to increase mechanical strength and to protect the collagen-based implant against enzymatic degradation by collagenases. Cross-linking also is believed to reduce the immunogenic potential of the acellularized matrix, due mainly to expression of galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose molecular epitopes. In its simplest form, cross-linking causes molecular bonds to form between native collagen molecules. Several steps during biologic mesh processing can cause matrix cross-linking, as with the use of detergents, enzymes, or high-energy beams for sterilization. These steps, in addition to intentional chemical modification of the matrix or terminal sterilization, all induce varying degrees of matrix cross-linking. The level of matrix cross-linking can be quantified by measuring the mesh collagen melting point. Higher degrees of cross-linking result in higher matrix melting points. Examination by electron microscopy also can be used to look for the preservation of biologic matrix structure. If the goal of biologic mesh–based soft tissue reconstruction is to support the repopulation of the donor matrix with host cells, like endothelial cells and fibroblasts, it appears that high levels of cross-linking impair that recellularization process. The host may even recognize a highly cross-linked material as foreign and induce a foreign body capsule response. A balance must therefore be struck between biologic mesh durability and regenerative potential. The end result is observed to be varying degrees of incorporation, resorption, or encapsulation. It appears that the outcome depends on material source, material processing, host response, surgical technique, and the level of wound contamination or inflammation. Further experimental studies and well-designed clinical trials are needed to characterize the optimum materials and methods.

The importance of preserving the native dermal matrix structure and to what degree is still debated. Cross-linking of dermal matrix xenografts was introduced as a method to increase mechanical strength and to protect the collagen-based implant against enzymatic degradation by collagenases. Cross-linking also is believed to reduce the immunogenic potential of the acellularized matrix, due mainly to expression of galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose molecular epitopes. In its simplest form, cross-linking causes molecular bonds to form between native collagen molecules. Several steps during biologic mesh processing can cause matrix cross-linking, as with the use of detergents, enzymes, or high-energy beams for sterilization. These steps, in addition to intentional chemical modification of the matrix or terminal sterilization, all induce varying degrees of matrix cross-linking. The level of matrix cross-linking can be quantified by measuring the mesh collagen melting point. Higher degrees of cross-linking result in higher matrix melting points. Examination by electron microscopy also can be used to look for the preservation of biologic matrix structure. If the goal of biologic mesh–based soft tissue reconstruction is to support the repopulation of the donor matrix with host cells, like endothelial cells and fibroblasts, it appears that high levels of cross-linking impair that recellularization process. The host may even recognize a highly cross-linked material as foreign and induce a foreign body capsule response. A balance must therefore be struck between biologic mesh durability and regenerative potential. The end result is observed to be varying degrees of incorporation, resorption, or encapsulation. It appears that the outcome depends on material source, material processing, host response, surgical technique, and the level of wound contamination or inflammation. Further experimental studies and well-designed clinical trials are needed to characterize the optimum materials and methods. Allografts and xenografts vary in the degree of terminal sterilization. Some methods limit terminal sterilization, using instead aseptic techniques. It is believed that this ensures preservation of extracellular matrix structure with improved biologic function following implantation. Other biologic mesh materials undergo true terminal sterilization, as with low-dose gamma irradiation. It is believed that this step may be important to minimizing infectious complications.

Allografts and xenografts vary in the degree of terminal sterilization. Some methods limit terminal sterilization, using instead aseptic techniques. It is believed that this ensures preservation of extracellular matrix structure with improved biologic function following implantation. Other biologic mesh materials undergo true terminal sterilization, as with low-dose gamma irradiation. It is believed that this step may be important to minimizing infectious complications.4 Mechanism of Action of Biologic Meshes (Table 18-2)

The primary function of soft tissue prostheses, whether synthetic or biologic meshes, is to provide immediate and long-term mechanical stability to the abdominal wall reconstruction. Level one evidence derived from a randomized, controlled trial found that the use of a reinforcing mesh prosthesis reduces the incisional hernia recurrence rate by 50%. The major risk of synthetic mesh implants is the permanent foreign body reaction, infection, encapsulation, extrusion, and erosion. There is now experimental and clinical evidence that biologic meshes may be repopulated with endothelial cells, revascularized and then incorporated into an abdominal wall reconstruction. It is the early establishment of a blood supply that is believed to establish improved resistance to infection. Further, as a blood supply is restored, other cells involved in tissue repair like inflammatory cells and fibroblasts may be recruited to promote more normal wound healing, and ideally, tissue regeneration.

The primary function of soft tissue prostheses, whether synthetic or biologic meshes, is to provide immediate and long-term mechanical stability to the abdominal wall reconstruction. Level one evidence derived from a randomized, controlled trial found that the use of a reinforcing mesh prosthesis reduces the incisional hernia recurrence rate by 50%. The major risk of synthetic mesh implants is the permanent foreign body reaction, infection, encapsulation, extrusion, and erosion. There is now experimental and clinical evidence that biologic meshes may be repopulated with endothelial cells, revascularized and then incorporated into an abdominal wall reconstruction. It is the early establishment of a blood supply that is believed to establish improved resistance to infection. Further, as a blood supply is restored, other cells involved in tissue repair like inflammatory cells and fibroblasts may be recruited to promote more normal wound healing, and ideally, tissue regeneration. Biologic meshes provide the potential for extracellular matrix directed repair signaling. Preserved vascular channels, for example, may allow endothelial cells or their precursors to enter the matrix, supporting angiogenesis by the process of inosculation. Other matrix molecules like fibronectin and glycosaminoglycans, when preserved, may act as signals for fibroblast integration and host collagen synthesis. The amount of other matrix molecules also varies widely depending on the biologic mesh tissue source. Human dermis, for example, contains relatively more elastin than porcine dermis, rendering it more compliant.

Biologic meshes provide the potential for extracellular matrix directed repair signaling. Preserved vascular channels, for example, may allow endothelial cells or their precursors to enter the matrix, supporting angiogenesis by the process of inosculation. Other matrix molecules like fibronectin and glycosaminoglycans, when preserved, may act as signals for fibroblast integration and host collagen synthesis. The amount of other matrix molecules also varies widely depending on the biologic mesh tissue source. Human dermis, for example, contains relatively more elastin than porcine dermis, rendering it more compliant.5 Reported Clinical Results with Biologic Meshes

The choice of biologic mesh material may be based on a variety of considerations, including characteristics of the patient and abdominal wall defect, surgeon familiarity with the material, and cost. The risk for surgical wound complication and subsequent infection may determine the selection of a synthetic versus a biologic repair material. On the balance, the biologic mesh material should provide sustained mechanical function resulting in an acceptable recurrence rate with resistance to wound infection, especially when compared to the synthetic counter parts.

The choice of biologic mesh material may be based on a variety of considerations, including characteristics of the patient and abdominal wall defect, surgeon familiarity with the material, and cost. The risk for surgical wound complication and subsequent infection may determine the selection of a synthetic versus a biologic repair material. On the balance, the biologic mesh material should provide sustained mechanical function resulting in an acceptable recurrence rate with resistance to wound infection, especially when compared to the synthetic counter parts. The majority of reports of surgeons’ experience with biologic mesh repairs come from single center, retrospective reviews. A randomized controlled trial of biologic mesh-based repairs versus synthetic mesh–based repairs for ventral hernia has never been reported. Multi-institutional, single-arm studies suggesting a proof-in-principle for the safety and efficacy of biologic mesh–based repairs are now appearing. It is broadly concluded that biologic mesh–based abdominal wall reconstructions can be safe and effective. Like most new techniques and technologies, it also appears surgical technique and material choice in the application of biologic meshes together affect outcomes. Without high level evidence, the decision tree remains primarily driven by surgeon experience and expert opinion.

The majority of reports of surgeons’ experience with biologic mesh repairs come from single center, retrospective reviews. A randomized controlled trial of biologic mesh-based repairs versus synthetic mesh–based repairs for ventral hernia has never been reported. Multi-institutional, single-arm studies suggesting a proof-in-principle for the safety and efficacy of biologic mesh–based repairs are now appearing. It is broadly concluded that biologic mesh–based abdominal wall reconstructions can be safe and effective. Like most new techniques and technologies, it also appears surgical technique and material choice in the application of biologic meshes together affect outcomes. Without high level evidence, the decision tree remains primarily driven by surgeon experience and expert opinion. The most frequent early application of biologic mesh for abdominal wall reconstruction was to manage complex ventral hernia repairs. This usually meant the need to perform an abdominal wall reconstruction in the setting of moderate or even significant contamination. Many surgeons reported the reliability of biologic mesh–based repairs, and the opportunity to avoid the technique of intentional, incisional ventral hernia. Numerous series now report the ability to safely salvage an abdominal wall repair when at increased risk for wound complication, with wound infection and recurrence rates that are acceptable when compared to more standard synthetic mesh–based repairs in lower risk settings. It was recognized that planned incisional hernia leads almost uniformly to progressive loss of domain; an increased risk of intestinal fistulization; and by definition, the requirement for further reconstructive procedures. Included was the frequent need for a skin graft with donor site morbidity.

The most frequent early application of biologic mesh for abdominal wall reconstruction was to manage complex ventral hernia repairs. This usually meant the need to perform an abdominal wall reconstruction in the setting of moderate or even significant contamination. Many surgeons reported the reliability of biologic mesh–based repairs, and the opportunity to avoid the technique of intentional, incisional ventral hernia. Numerous series now report the ability to safely salvage an abdominal wall repair when at increased risk for wound complication, with wound infection and recurrence rates that are acceptable when compared to more standard synthetic mesh–based repairs in lower risk settings. It was recognized that planned incisional hernia leads almost uniformly to progressive loss of domain; an increased risk of intestinal fistulization; and by definition, the requirement for further reconstructive procedures. Included was the frequent need for a skin graft with donor site morbidity. The increased use of decompressive laparotomies and damage control laparotomies resulted in an increased number of surgical patients with complex abdominal wall injuries. The ability to manage the open abdomen over a prolonged period of time supported this clinical approach. Often, at the time of abdominal wall repair, a reinforcing material was needed by the surgeon because of contamination and the risk of wound healing delay, hypotensive hypoperfusion of the abdominal wall, or other common comorbidities like obesity or immunosuppression. Biologic mesh reinforced abdominal wall repairs are reported as safe and reliable in this setting as well.

The increased use of decompressive laparotomies and damage control laparotomies resulted in an increased number of surgical patients with complex abdominal wall injuries. The ability to manage the open abdomen over a prolonged period of time supported this clinical approach. Often, at the time of abdominal wall repair, a reinforcing material was needed by the surgeon because of contamination and the risk of wound healing delay, hypotensive hypoperfusion of the abdominal wall, or other common comorbidities like obesity or immunosuppression. Biologic mesh reinforced abdominal wall repairs are reported as safe and reliable in this setting as well. Accumulating reports of the risk for the intraperitoneal placement of synthetic onlay meshes (IPOM) also drove the application of biologic meshes to abdominal wall reconstruction. The U.S. NSQuIP database and Dutch Hernia Registry found that reoperation in the presence of a prior synthetic mesh in the intraperitoneal position significantly increased the risk of unplanned bowel injury and resection from 3% to 23 % .

Accumulating reports of the risk for the intraperitoneal placement of synthetic onlay meshes (IPOM) also drove the application of biologic meshes to abdominal wall reconstruction. The U.S. NSQuIP database and Dutch Hernia Registry found that reoperation in the presence of a prior synthetic mesh in the intraperitoneal position significantly increased the risk of unplanned bowel injury and resection from 3% to 23 % . Some surgeons and centers have reported recurrence rates for incisional hernia as high as 100% when using biologic meshes. A consensus is emerging that this is not the universal experience and that some of this is due to surgical technique and some of it is due to material properties. It appears that the use of biologic meshes to bridge a gap in the abdominal wall leads to a high incidence of “bulging” or recurrence. Regardless of the definition of recurrent incisional hernia, a bulging defect is visible, it may impair abdominal wall function as during a sit-up, and usually the patient is displeased with the result. Some of this may be an inherent biologic limitation of the biologic meshes, in that in order for revascularization and general recellularization to occur, the biologic implant must be in contact with well-perfused host tissue. It now appears that biologic meshes perform better when used as reinforcing materials to an already reconstructed abdominal wall, as after component separation. The human allograft dermis also contains more elastin that may result in more stretching, leading to a clinical bulge. It is not clear whether porcine dermis or intestinal submucosa does this less or should be held to the same limitations.

Some surgeons and centers have reported recurrence rates for incisional hernia as high as 100% when using biologic meshes. A consensus is emerging that this is not the universal experience and that some of this is due to surgical technique and some of it is due to material properties. It appears that the use of biologic meshes to bridge a gap in the abdominal wall leads to a high incidence of “bulging” or recurrence. Regardless of the definition of recurrent incisional hernia, a bulging defect is visible, it may impair abdominal wall function as during a sit-up, and usually the patient is displeased with the result. Some of this may be an inherent biologic limitation of the biologic meshes, in that in order for revascularization and general recellularization to occur, the biologic implant must be in contact with well-perfused host tissue. It now appears that biologic meshes perform better when used as reinforcing materials to an already reconstructed abdominal wall, as after component separation. The human allograft dermis also contains more elastin that may result in more stretching, leading to a clinical bulge. It is not clear whether porcine dermis or intestinal submucosa does this less or should be held to the same limitations. Currently, biologic meshes are very compliant, especially when compared to most synthetic meshes. This can make handling more difficult and most surgeons experience a learning curve for understanding the unique material properties. This has resulted in limited adaptation to laparoscopic applications, for example. The concern for bulging following a bridging technique also has limited the development of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair using biologic meshes.

Currently, biologic meshes are very compliant, especially when compared to most synthetic meshes. This can make handling more difficult and most surgeons experience a learning curve for understanding the unique material properties. This has resulted in limited adaptation to laparoscopic applications, for example. The concern for bulging following a bridging technique also has limited the development of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair using biologic meshes. No head-to-head comparative trials have been performed to date evaluating different biologic repair materials in incisional hernia repair, and differentiation between products is based on early reported findings with only a limited number of the available prostheses. Detailed human and animal data describing the qualities of biologic repair materials are only available for some of these prostheses.

No head-to-head comparative trials have been performed to date evaluating different biologic repair materials in incisional hernia repair, and differentiation between products is based on early reported findings with only a limited number of the available prostheses. Detailed human and animal data describing the qualities of biologic repair materials are only available for some of these prostheses.Breuing K., Butler C.E., Ferzoco S., et al. Incisional ventral hernias: Review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. 2010;148(3):544-558.

Diaz J.J.Jr., Conquest A.M., Ferzoco S.J., Vargo D., Miller P., Wu Y.C., et al. Multi-institutional experience using human acellular dermal matrix for ventral hernia repair in a compromised surgical field. Arch Surg. 2009 Mar;144(3):209-215.

Espinosa-de-Los-Monteros A., de la Torre J.I., Marrero I., Andrades P., Davis M.R., Vasconez L.O. Utilization of human cadaveric acellular dermis for abdominal hernia reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2007 Mar;58(3):264-267.

Franz M.G. The biology of hernia formation. Surg Clin North Am. 2008 Feb;88(1):1-15. vii

Gray S.H., Vick C.C., Graham L.A., Finan K.R., Neumayer L.A., Hawn M.T. Risk of complications from enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection during elective hernia repair. Arch Surg. 2008 Jun;143(6):582-586.

Halm J.A., de Wall L.L., Steyerberg E.W., Jeekel J., Lange J.F. Intraperitoneal polypropylene mesh hernia repair complicates subsequent abdominal surgery. World J Surg. 2007 Feb;31(2):423-429.

Luijendijk R.W., Hop W.C.J., van den Tol P., de Lange D.C.D., Braaksma M.M.J., Ijzermans J.N.M., et al. A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000 Aug 10;343(6):392-398.